Language the 'Foxp2' Gene's Journey Through Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Saloni Krishnan Curriculum Vitae

SALONI KRISHNAN CURRICULUM VITAE WEB CONTACT @salonikrishnan Dept. of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, 15 Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3UD github.com/salonikrishnan Corpus Christi College, University of Oxford, Merton Street, Oxford OX1 4JF osf.io/y4238 t: 07837935161 | e: [email protected] | w: www.salonikrishnan.com RESEARCH INTERESTS My research aims to identify brain changes that underlie childhood speech and language disorders such as developmental language disorder or stuttering, and use this knowledge to improve existing clinical tools. I am also interested in research questions that relate to this goal, such as how brain circuits for speech/language change over childhood, what factors explain individual differences in speech/ language performance, how speech/language learning can be improved, and what neural changes occur as a function of learning and training in the auditory-motor domain. To address my research questions, I use classical behavioural paradigms, as well as structural and functional magnetic resonance imaging. EXPERIENCE Royal Holloway, University of London Lecturer April 2019 - present University of Oxford Postdoctoral Research Associate Dept. of Experimental Psychology Neural basis of developmental disorders (stuttering, developmental language disorder) 2015- 2019 Funding: Wellcome Trust Principal Research Fellowship to Professor Dorothy Bishop, then Medical Research Council research grant to Professor Kate Watkins Corpus Christi College Junior Research Fellow 2017 - 2020 Non-stipendiary appointment -

Planum Temporale Asymmetry in People Who Stutter

Journal of Fluency Disorders xxx (xxxx) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Fluency Disorders journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jfludis Planum temporale asymmetry in people who stutter Patricia M. Gougha, Emily L. Connallyb, Peter Howellc, David Wardd, ⁎ Jennifer Chestersb, Kate E. Watkinsb, a Department of Psychology, Maynooth University, Maynooth, Co. Kildare, Ireland b Department of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3UD, UK c Department of Psychology, University College London, Bedford Way, London, WC1E 6BT, UK d School of Psychology and Clinical Language Sciences, University of Reading, Harry Pitt Building, Earley Gate, Reading, RG6 7BE, UK ABSTRACT Purpose: Previous studies have reported that the planum temporale – a language-related struc- ture that normally shows a leftward asymmetry – had reduced asymmetry in people who stutter (PWS) and reversed asymmetry in those with severe stuttering. These findings are consistent with the theory that altered language lateralization may be a cause or consequence of stuttering. Here, we re-examined these findings in a larger sample of PWS. Methods: We evaluated planum temporale asymmetry in structural MRI scans obtained from 67 PWS and 63 age-matched controls using: 1) manual measurements of the surface area; 2) voxel- based morphometry to automatically calculate grey matter density. We examined the influences of gender, age, and stuttering severity on planum temporale asymmetry. Results: The size of the planum temporale and its asymmetry were not different in PWS compared with Controls using either the manual or the automated method. Both groups showed a sig- nificant leftwards asymmetry on average (about one-third of PWS and Controls showed right- ward asymmetry). -

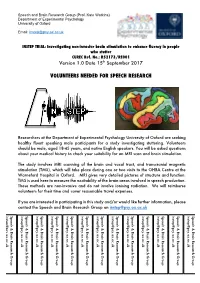

Volunteers Needed for Speech Research

Speech and Brain Research Group (Prof. Kate Watkins) Department of Experimental Psychology University of Oxford Email: [email protected] INSTEP TRIAL: Investigating non-invasive brain stimulation to enhance fluency in people who stutter CUREC Ref. No.: R52173/RE001 Version 1.0 Date 15th September 2017 VOLUNTEERS NEEDED FOR SPEECH RESEARCH Researchers at the Department of Experimental Psychology University of Oxford are seeking healthy fluent speaking male participants for a study investigating stuttering. Volunteers should be male, aged 18-45 years, and native English speakers. You will be asked questions about your medical history to check your suitability for an MRI scan and brain stimulation. The study involves MRI scanning of the brain and vocal tract, and transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), which will take place during one or two visits to the OHBA Centre at the Warneford Hospital in Oxford. MRI gives very detailed pictures of structure and function. TMS is used here to measure the excitability of the brain areas involved in speech production. These methods are non-invasive and do not involve ionising radiation. We will reimburse volunteers for their time and cover reasonable travel expenses. If you are interested in participating in this study and/or would like further information, please contact the Speech and Brain Research Group on [email protected] [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group [email protected] Speech & Brain Research Group Research Group Research . -

NEUROPSYCHOLOGIA 83 Volume 83 , March 2016

NEUROPSYCHOLOGIA 83 Volume 83 , March 2016 A n international journal in behavioural and cognitive neuroscience NEURO Volume 83 March 2016 PSYCHOLOGIA Special Issue Functional Selectivity in Perceptual and Cognitive Systems - A Tribute to Shlomo Bentin (1946-2012) Guest Editors Vol. NEUROPSYCHOLOGIA Kalanit Grill-Spector, Leon Deouell, Rafael Malach, Bruno Rossion and Micah Murray An international journal in behavioural and cognitive neuroscience 83 ( 2016 Contents ) 1 L. Deouell , K. Grill-Spector , R. Malach , 1 Introduction to the special issue on functional selectivity in – M.M. Murray and B. Rossion perceptual and cognitive systems - a tribute to Shlomo Bentin 282 (1946-2012) G. Yovel 5 Neural and cognitive face-selective markers: An integrative review C. Jacques , N. Witthoft , K.S. Weiner , 14 Corresponding ECoG and fMRI category-selective signals in human B.L. Foster , V. Rangarajan , D. Hermes , ventral temporal cortex K.J. Miller , J. Parvizi and K. Grill-Spector V. Rangarajan and J. Parvizi 29 Functional asymmetry between the left and right human fusiform gyrus explored through electrical brain stimulation N. Freund , C.E. Valencia-Alfonso , J. Kirsch , 37 Asymmetric top-down modulation of ascending visual pathways K. Brodmann , M. Manns and O. G ü nt ü rk ü n in pigeons K.S. Weiner and K. Zilles 48 The anatomical and functional specialization of the fusiform gyrus 63 Visual expertise for horses in a case of congenital prosopagnosia N. Weiss , E. Mardo and G. Avidan Special Issue: Functional Selectivity J.J.S. Barton and S.L. Corrow 76 Selectivity in acquired prosopagnosia: The segregation of divergent and convergent operations A. -

Full Programme – 4-6 July 2017

HEA Annual Conference 2017 #HEAconf17 Generation TEF: Teaching in the spotlight Full programme – 4-6 July 2017 Day 1 4 July 2017 Arts and Humanities strand Day 1 4 July 2017 Health and Social Care strand Day 2 5 July 2017 Strategy and Sector Priorities strand Day 3 6 July 2017 Social Sciences strand Day 3 6 July 2017 STEM strand 1 ^ TOP ^ HEA Annual Conference 2017 #HEAconf17 Generation TEF: Teaching in the spotlight Day 1: 4 July 2017 – Arts and Humanities strand programme Session Type Details Room 9.00-9.45 Registration Refreshments available 9.45-10.00 Welcome C9 10.00-11.00 Keynote C9 Dr Alison James, Head of Learning and Teaching and Acting Director of Academic Quality/Development (University of Winchester) Finding magic despite the metrics 11.00-11.30 Refreshments 11.30-12.00 AH1.3 Oral ‘The Kingdom of Yes’: Students involvement in 1st Year D5 presentation curriculum design, Lisa Gaughan (University of Lincoln) AH1.4 Oral Out of study experiences: The power of different learning D6 presentation environments to inspire student engagement, Polly Palmer (University of Hertfordshire) AH1.5 Oral Teaching excellence: Conceptions and practice in the Humanities D7 presentation and Social Sciences, John Sanders (Open University) & Anna Mountford-Zimbars (Kings College London) AH1.8 Oral Digital solutions to student feedback in the Performing Arts, E5 presentation Robert Dean (University of Lincoln) AH1.9 Oral Bristol Parkhive: An interdisciplinary approach to E6 presentation employability for Arts, Humanities and Education students in a supercomplex -

4 Abstract 563.19 Summary Senior Author: Kate E. Watkins, Phd (44-18

Abstract 563.19 Summary Senior author: Kate E. Watkins, PhD (44-18) 6522-2581 University of Oxford [email protected] Oxford, United Kingdom People Who Stutter Show Abnormal Brain Activity When Reading and Listening Study suggests abnormalities exist in speech processing as well as production A new imaging study finds that people who stutter show abnormal brain activity even when reading or listening. The results suggest that individuals who stutter have impaired speech due to irregular brain circuits that affect several language processing areas — not just the ones for speech production. The research was presented at Neuroscience 2010, the annual meeting of the Society for Neuroscience and the world’s largest source of emerging news about brain science and health. Stuttering affects about one in every 20 children; most grow out of it, but one in five continues to struggle. While the particular cause of stuttering is still unknown, previous studies showed reduced activity in brain areas associated with listening, and increased activity in areas involved in speech and movement. In the new study, researchers considered whether irregular activity would also be apparent when stuttering speakers silently read. “If those patterns are also abnormal, the differences could be considered typical of the stuttering brain and not just the result of the difficulties that people who stutter have with speech production,” said senior author Kate Watkins, PhD, of the University of Oxford. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), Watkins and her team compared the brain activity in 12 adults who stutter with 12 adults who do not. The researchers conducted the scans in three trials: in one, volunteers simply listened to sentences; in the second, they read sentences silently; in the third, they read sentences silently while another person read the same sentence aloud. -

Download Preprint

1 Speech movement variability in people who stutter: a 2 vocal-tract MRI study 3 4 5 6 Charlotte E. E. Wiltshire, Mark Chiew, Jennifer Chesters, Máiréad P. Healy & Kate E. Watkins 7 Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, Department of Experimental Psychology, 8 Radcliffe Observatory Quarter, University of Oxford, OX2 6GG, UK 9 10 [email protected] (corresponding author) 11 [email protected] 12 [email protected] 13 [email protected] 14 [email protected] 15 16 Declarations of interest: none 17 18 19 Abstract 20 21 Purpose: People who stutter (PWS) have more unstable speech motor systems than people 22 who are typically fluent (PWTF). Here, we used real-time MRI of the vocal tract to assess 23 variability and duration of movements of different articulators in PWS and PWTF during fluent 24 speech production. 25 Method: The vocal tracts of 28 adults with moderate to severe stuttering and 20 PWTF were 26 scanned using MRI while repeating simple and complex pseudowords. Mid-sagittal images of 27 the vocal tract from lips to larynx were reconstructed at 33.3 frames per second. For each 1 28 participant, we measured the variability and duration of movements across multiple 29 repetitions of the pseudowords in three selected articulators: the lips, tongue body, and velum. 30 Results: PWS showed significantly greater speech movement variability than PWTF during 31 fluent repetitions of pseudowords. The group difference was most evident for measurements 32 of lip aperture, as reported previously, but here we report that movements of the tongue body 33 and velum were also affected during the same utterances. -

Modulation of Motor Excitability During Speech Perception: the Role of Broca’S Area

Modulation of Motor Excitability during Speech Perception: The Role of Broca’s Area Kate Watkins and Toma´ˇs Paus Abstract & Studies in both human and nonhuman primates indicate regions that modulate the excitability of the motor system that motor and premotor cortical regions participate in during speech perception. Our results show that during auditory and visual perception of actions. Previous studies, auditory speech perception, there is increased excitability of using transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), showed that motor system underlying speech production and that this perceiving visual and auditory speech increased the excitability increase is significantly correlated with activity in the posterior of the orofacial motor system during speech perception. Such part of the left inferior frontal gyrus (Broca’s area). We propose studies, however, cannot tell us which brain regions mediate that this area ‘‘primes’’ the motor system in response to heard this effect. In this study, we used the technique of combining speech even when no speech output is required and, as such, positron emission tomography with TMS to identify the brain operates at the interface of perception and action. & INTRODUCTION perceptions to phonetic gestures and that such a system The division between the brain regions involved in might be at the origin of the evolution of human speech action production and perception is becoming increas- (Rizzolatti & Arbib, 1998; Gallese et al., 1996). ingly blurred as evidence accumulates that in the In humans, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) primate brain, motor and premotor regions also par- applied over the primary motor cortex has been used ticipate in action perception. In the domain of speech to probe its excitability during visual perception of perception this notion is not new. -

An Fmri Study of Initiation and Inhibition of Manual Responses in People Who Stutter

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.07.286013; this version posted September 7, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. An fMRI study of initiation and inhibition of manual responses in people who stutter Charlotte E. E. Wiltshire1, Jennifer Chesters1, Saloni Krishnan1,2, Máiréad P. Healy1, Kate E. Watkins1 1Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, Department of Experimental Psychology, Radcliffe Observatory Quarter, University of Oxford, OX2 6GG, UK 2Department of Psychology, Royal Holloway, University of London, Egham Hill, Surrey TW20 0EX, UK [email protected] (corresponding author); Orcid ID: 0000 0001 8523 6642 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Key Words: Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Stuttering, Developmental Basal Ganglia Speech Inhibition, Psychological Prefrontal Cortex Data Availability Statement: The behavioural data that support the findings of this study are openly available on OSF at DOI 10.17605/OSF.IO/ZJSWA. The MRI data that support the findings of this study are openly available in Neurovault at https://identifiers.org/neurovault.collection:8669. bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.07.286013; this version posted September 7, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

97Th Annual Honors Convocation

97TH ANNUAL HONORS CONVOCATION MARCH 15, 2020 2:00 P.M. HILL AUDITORIUM This year marks the 97th Honors Convocation held at the University of Michigan since the first was instituted on May 13, 1924, by President Marion LeRoy Burton. On these occasions, the University publicly recognizes and commends the undergraduate students in its schools and colleges who have earned distinguished academic records or have excelled as leaders in the community. It is with great pride that the University honors those students who have most clearly and effectively demonstrated academic excellence, dynamic leadership, and inspirational volunteerism. The Honors Convocation ranks with the Commencement Exercises as among the most important ceremonies of the University year. The names of the students who are honored for outstanding achievement this year appear in this program. They include all students who have earned University Honors in both Winter 2019 and Fall 2019, plus all seniors who have earned University Honors in either Winter 2019 or Fall 2019. The William J. Branstrom Freshman Prize recipients are listed, as well – recognizing first year undergraduate students whose academic achievement during their first semester on campus place them in the upper five percent of their school or college class. James B. Angell Scholars – students who receive all “A” grades over consecutive terms – are given a special place in the program. In addition, the student speaker is recognized individually for exemplary contributions to the University community. To all honored students, and to their parents, the University extends its hearty congratulations. Susan M. Collins • Acting Provost and Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs Honored Students Honored Faculty Faculty Colleagues and Friends of the University It is a pleasure to welcome you to the 97th University of Michigan Honors Convocation. -

Phonology and Learning to Read in Normal and Hemiplegic Children

PHONOLOGY AND LEARNING TO READ IN NORMAL AND HEMIPLEGIC CHILDREN VALERIE MUTER Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy INSTITUTE OF CHILD HEALTH, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON APRIL, 1994 ProQuest Number: U062557 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest U062557 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 2 Acknowledgements I am most grateful to my supervisor, Dr Faraneh Vargha-Khadem who instigated the project, generated my interest in working with hemiplegic children and who provided valuable insights into the neuropsychological issues discussed in the second half of the thesis. I am indebted to my advisor and friend. Professor Margaret Snowling, University of Newcastle, who unstintingly gave advice, encouragement and support throughout the project. Her contribution provided direction to the first half of the thesis, and her critical comments and editing skills have been greatly appreciated. Enormous thanks are due to Sara Taylor, now at University College, London, who helped gather the copious data, and who maintained a great commitment to the project throughout its length. -

Praxic and Nonverbal Cognitive Deficits in a Large Family with a Genetically

Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 92, pp. 930-933, January 1995 Psychology Praxic and nonverbal cognitive deficits in a large family with a genetically transmitted speech and language disorder FARANEH VARGHA-KHADEM*t, KATE WATKINS*t, KATIE ALCOCKt, PAUL FLETCHER§, AND RICHARD PASSINGHAMt *Neurosciences Unit, Institute of Child Health, The Wolfson Centre, Mecklenburgh Square, London, WC1N 2AP, United Kingdom; tDepartment of Psychological Medicine, Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children National Health Service Trust, Great Ormond Street, London, WC1N 3JH, United Kingdom; tDepartment of Experimental Psychology, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford, OX1 3UD, United Kingdom; and §Department of Linguistic Science, University of Reading, P.O. Box 218, Reading, RG6 2AA, United Kingdom Communicated by Mortimer Mishkin, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, September 26, 1994 ABSTRACT A pronounced speech and language disorder taught a sign system to augment their speech. Despite intensive affecting half of the 30 members of the four-generational KE speech therapy, to the naive listener their discourse is still family has been attributed by some researchers to a specific unintelligible over the telephone and on audio tapes, partic- defect in the generation of morphosyntactic rules. The re- ularly when heard out of context. ported selectivity of the impairment has led to the view that Twenty-one members of the KE family (affected, n = 13; the affected members suffer from a grammar-specific disor- unaffected, n = 8) were evaluated on tests of language der. Our investigations ofthe same KE family indicate that the production and comprehension, including grammar, phonol- inherited disorder has a broad phenotype which transcends ogy, reading, and writing.