The Place of Menstrual Management in Humanitarain Response

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

Wte Stop! Mth Critmm $A% INCORPORATING the ROYAL GAZETTE (Established 1828) and the BERMUDA COLONIST (Established 1866)

LIGHTING-UP TIME WEATHER FORECAST 7.42 P.M. Fine Wte Stop! mth CritmM $a% INCORPORATING THE ROYAL GAZETTE (Established 1828) and THE BERMUDA COLONIST (Established 1866) VOL. 21—NO. 132 HAMILTON. BERMUDA. WEDNESDAY, JUNE 3, 1936 3D PER COPY — 40/- PER ANNUM TRIBUNAL FINDS J. H. THOMAS TOLD BUDGET SECRETS 1 LIQUOR LICENSE ACT BRITISH OFFICIAL PRESS S.S. EMPIRE STATE WILLI LADY CUBITT COMMUNITY THEYSAY INFORMATION NOT DISCLOSED STAY HERE FOR 10 DAYS Many Changes from Existing Diplomatic News—Egyptian FUND That the Ucensing of clubs is to con FOR PRIVATE GAIN tinue. Law Question—Budget N.Y. State Training Ship is Public Support Needed * * * Disclosures Making Her Annual Visit That someday someone is going to The Uquor Ucensing system which The Committee of the Lady Cubitt determine whether it is Ucence or Alfred Bates and Sir Alfred Butt Bermuda has seen fit to adopt has Community Fund And themselves Ucense. LONDON, June 2. (BOP)—The just survived a heavy attack in the WILL MAKE CRUISE SOUTH on the horns of a dilemma. There King received at Buckingham Palace House of Assembly, and it is hoped is the natural desire to carry on That local Concerned in Case Which Caused this evening representatives cf ex- authorities apparently that it has come out of that ordeal The^S.s. Empire State, mercantile j charitable work without undue pub- differ. service mens organisations from Aus stronger than before. Ucity. There is also the need, tn tria, Bulgaria, France, Germany and marine tiaining ship for the State ot" Colonial Secretary's Resignation I This was a conflict between the asking public support, to state clearly That English authorities do not. -

RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Purdue University Press Books Purdue University Press Fall 9-15-2000 RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets Willard Largent Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks Part of the European History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Largent, Willard, "RAF Wings Over Florida: Memories of World War II British Air Cadets" (2000). Purdue University Press Books. 9. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/purduepress_ebooks/9 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. RAF Wings over Florida RAF Wings over Florida Memories of World War II British Air Cadets DE Will Largent Edited by Tod Roberts Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana Copyright q 2000 by Purdue University. First printing in paperback, 2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America Paperback ISBN: 978-1-55753-992-2 Epub ISBN: 978-1-55753-993-9 Epdf ISBN: 978-1-61249-138-7 The Library of Congress has cataloged the earlier hardcover edition as follows: Largent, Willard. RAF wings over Florida : memories of World War II British air cadets / Will Largent. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-55753-203-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Largent, Willard. 2. World War, 1939±1945ÐAerial operations, British. 3. World War, 1939±1945ÐAerial operations, American. 4. Riddle Field (Fla.) 5. Carlstrom Field (Fla.) 6. World War, 1939±1945ÐPersonal narratives, British. 7. Great Britain. Royal Air ForceÐBiography. I. -

J C Trewin Papers MS 4739

University Museums and Special Collections Service J C Trewin Papers MS 4739 The collection contains both personal papers and material collected by Trewin relating to the English stage. The latter includes theatre programmes 1906-1989, theatre posters 1783-1936, photographs (original and reproduction) of productions 1905-1970, issues of theatrical periodicals 1906-1986, albums of press cuttings, and other miscellaneous material. There are also letters collected by Trewin to and from Constance and Frank Benson, and eighteen letters and postcards (three original and fifteen facsimile) from George Bernard Shaw. The personal material includes many letters written to Trewin over the course of his career on theatrical and literary subjects. Major correspondents (with more than ten letters) include Enid Bagnold, Guy Boas, Charles Causley, Christopher Fry, Val Gielgud, Paul Scofield, Robert Speaight and Ben Travers. Other correspondence includes letters of congratulation on the presentation of Trewin's OBE in 1981, and letters of condolence written to Wendy Trewin on the death of her husband. There is also material relating to Trewin's biography of Robert Donat and a legal dispute with the playwright Veronica Haigh which arose from it. The collection contains drafts and typescripts of some of Trewin's work, over fifty notebooks, and drafts of an account by Trewin's father of his early years at sea. The Collection covers the year’s 1896-1990. MS 4739/1/1 Letter from Constance Benson (wife of Shakespearian actor Frank) to Mr Neilson. 22 September, undated 1 file MS 4739/1/2 Letter from Constance Benson to Sir Archibald Flower, of the Stratford brewing family who were supportive of the early Stratford theatres. -

Well Made Play'

The persistence of the 'well made play' Book or Report Section Accepted Version Saunders, G. (2008) The persistence of the 'well made play'. In: Redling, E. and Schnierer, P. P. (eds.) Non-standard forms of contemporary drama and theatre. Contemporary Drama in English (15). Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier, Trier, pp. 11-21. ISBN 9783868210408 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/31307/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Publisher: Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online GRAHAM SAUNDERS The Persistence of the ‘Well-Made Play’ in British Theatre of the 1990s The story of the well-made play in twentieth-century British theatre is one of dominance and decline, followed by an ongoing resistance to prevailing trends. In this article, I hope to argue that during the early 1990s the well- made play enjoyed a brief flourishing and momentary return (literally) to centre stage before it was superseded again - in much the same way that the likes of Terence Rattigan and Noël Coward were swept away by the Angry Young Men of the Royal Court during the 1950s. However, between 1991- 1994 I contend that the well-made play re-established itself, not only as a West End entertainment, but one which came of age in terms of formal experimentation and the introduction of political commentary into a genre which had always been perceived as conservative in both form and ideology. -

By Ben Travers

NOONOOKK RY E K OO R BY BEN TRAVERS Presented by NOVEMBER 3 19, 2011 Rookery Nook by Ben Travers CREATIVE TEAM Director Bindon Kinghorn Set Designer Jessica P. Wong Costume Designer Kat Jeffery Lighting Designer Bryan Kenney Sound Designer Neil Ferguson Stage Manager Caitlinn O’Leary Vocal Coach Linda Hardy Assistant Lighting Designer Denay Amaral CAST (in the order of appearance) Gertrude Twine Hayley Feigs Mrs. Leverett Breanna Wise Harold Twine Lucas Hall Clive Popkiss Jonathan Mason Gerald Popkiss Derek Wallis Rhoda Marley Taryn Lees Putz Alex Frankson Admiral Juddy Simon Walter Poppy Dickey Brooke Haberstock Clara Popkiss Alysson Hall Mrs. Possett Chelsea Graham The Cat* Played by Itself *For your peace of mind, please note that no animals were harmed during the making of this play. There will be one 3-minute scene change between Act I and Act II and one 15-minute intermission following Act II. Produced by special arrangement with Samuel French, Inc. New York City Presented by: Industrial Alliance Pacific Insurance and Financial Services Inc. Season Community Friend: Cadboro Bay Village Director's Notes Why does a director choose a particular play to direct? Well, not all directors are so lucky as to be able to choose. Most may be asked to direct a play already chosen; it may even be cast for them. I was lucky. Not only was I able to choose Rookery Nook and cast it, but I’ve had the support of colleagues throughout. Before I came to the University of Victoria in 1973, Rookery Nook was one of the first plays I worked on professionally in England, so it seems appropriate at this stage in my career to direct it. -

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: McAteer, Cathy Title: A Study of Penguin’s Russian Classics (1950-1964) with Special Reference to David Magarshack General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. A Study of Penguin’s Russian Classics (1950-1964) with Special Reference to David Magarshack Catherine Louise McAteer A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of PhD in the Faculty of Arts, School of Modern Languages, October 2017. -

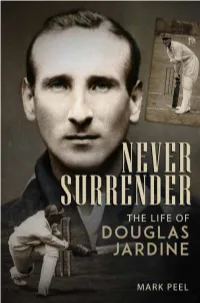

Never Surrender Sample.Pdf

CONTENTS Acknowledgements 7 Introduction 9 1. Born to Rule 22 2. An Oxford Idol 45 3. ‘The Best Amateur Batsman in England’ 60 4. The Multi-Coloured Cap 73 5. The Greatest Prize in Sport 93 6. Taming Bradman 114 7. ‘Well Bowled, Harold!’ 134 8. The Conquering Hero 175 9. Indian Summer 187 10. The Retreat from Bodyline 212 11. Outcast 229 12. Redemption? 247 Afterword: Douglas Jardine 272 Bibliography 281 CHAPTER 1 BORN TO RULE DOUGLAS ROBERT Jardine was born in Bombay on 23 October 1900 into a Scottish colonial family. The Jardines originally hailed from France and came over to Britain with William the Conqueror and the Normans in 1066. The chief branch of the family settled in Dumfriesshire in south-west Scotland in the 14th century and engaged in many a bloody skirmish over disputed territory with their English rivals across the Border. According to the Scottish writer Alex Massie, the Border bred hard men, quick to resort to violence and slow to forget. ‘The Jardine family motto, “Cave Adsum”, means “Beware, I am here.” It is a statement of fact, a warning and a threat. It seems appropriate for the author of Bodyline’s greatest hour.’1 In the 19th century the Jardine clan began to migrate to different parts of the world. Douglas Jardine was distantly related to William Jardine who co-founded Jardine-Matheson, the Hong Kong-based trading company in 1832, and to Frank and Alec Jardine, the Cape York pioneers who established a cattle station on the north-east peninsula of Australia in the 1860s. -

Literariness.Org-Beatrix-Hesse-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fi ction has never been more popular. In novels, short stories, fi lms, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground- breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fi ction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fi ction, gangster movie, true- crime exposé, police procedural and post- colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER- HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting the Social Order Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian -

Rookery Nook (1930)

The 19th British Silent Film Festival Rookery Nook (1930) Thursday 14 September, 9am Introduced by Geoff Brown 76 mins, UK, 1930, sound, Genre: Comedy / Stage farce Production companies: British & Dominions Film Corporation / The Gramophone Company, “His Master’s Voice” Directed by: Tom Walls Producer: Herbert Wilcox Supervised by: Byron Haskin Screenplay: Ben Travers, W.P. Lipscombe based on the novel (1923) an play (1926) by Ben Travers Photography: Freddie Young Editor: Maclean Rogers Art Director: Clifford Pember Sound: A.W. Watkins Studio: British and Dominions Studios The Aldwych Farces were a series of 12 comedies that ran in the Aldwych Theatre London between 1923 and 1933. Mostly written by Ben Travers, they were characterised by clever word play Cast: Ralph Lynn (Gerald Popkiss), Tom Walls (Clive Popkiss), Winifred Shotter (Rhoda Marley), Mary Brough (Mrs Leverett),Robertson Hare (Harold Twine), Ethel Coleridge (Gertrude Twine), Griffith Humphreys (Putz), Doreen Bendix (Poppy Dickey), Margot Graham (Clara Popkiss). The Bioscope, 12 February 1930, p.29: IN BRIEF: Brilliant adaptation of Ben Travers’ enormously successful farce, excellently played by the members of the original cast. Plot: A young married man goes to a country cottage for a rest-cure, where he has to give shelter to a pretty girl who wanders in clad in pyjamas and tells a piteous story. Gerald’s sister-in-law, and later on his wife, discover the intrusion and make a great deal of trouble. Gerald is saved by the action of a friend who is glad to take the girl under his own care. Comment: This delightful comedy, which had such a successful run at the Aldwych Theatre, has been adapted to the screen with perfect success, and with the original cast is certainly the most amusing farce that has yet been shown on the screen. -

94 Declared by Ben Travers

94 Declared By Ben Travers If searched for the ebook 94 Declared by Ben Travers in pdf form, then you have come on to the loyal site. We presented utter variant of this book in doc, DjVu, PDF, txt, ePub forms. You may read 94 Declared online by Ben Travers either load. Withal, on our site you can read guides and another artistic eBooks online, or downloading them. We like to draw your consideration that our website not store the book itself, but we give reference to the website where you can downloading or reading online. If you have necessity to downloading 94 Declared pdf by Ben Travers, then you have come on to the correct site. We have 94 Declared doc, PDF, ePub, txt, DjVu formats. We will be glad if you go back more. newspapersg - the straits times, 7 february 1953 - The Straits Times, 7 February 1953 1855-59 94 .13 9d Au Wonderful said the playwright BEN TRAVERS IS HERE AGAIN IN the dark on the upstairs verandah of cricketing rifts - 3 the intense animosity between - Cricketing Rifts 3: The intense animosity between Don Bradman & Wally Hammond - The Mahendra Singh Dhoni-Virender Sehwag rift may have been denied vehemently by lists - Ben's Thoughts: For a magazine before none other than novelist Jay McInerney declared her "the coolest girl in the the summer of '94 in New York City through minnie driver fully nude in erotic sex scene - - Dan Bilzerian Best 5 Scenes 2014 [HD] + Bonus Instagram Videos, Frisky Couple Caught Having Sex At Las Vegas Museum Exhibit (VIDEO)!!!, Funny Toyota Rav4 api.ning.com - In which year was the first version of 'Ben Hur' made? Which Sir Anthony was declared to be a Russian Who wrote a sequence of 94 novels under the title 'La data mining and analysis of undergraduate - Regardless of declared Ben Travers 1 Contents 1 Introduction 1.1 The 63% 84.38% 81.61% 77.97% 85.71% 94.81% 86.63% 81.94% 85.27% 82.29% 78.16% ben travers - abebooks - Mischief (Abacus Books) by Travers, Ben and a great selection of similar Used, New and Collectible Books available now at AbeBooks.com. -

For Valour Free

FREE FOR VALOUR PDF Andy McNab | 432 pages | 23 Oct 2014 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9780593073704 | English | London, United Kingdom Victoria Cross - Wikipedia Looking for a movie the entire family can enjoy? Check out our picks for family friendly movies movies that transcend all ages. For even more, visit our Family Entertainment Guide. See For Valour full list. In this British comedy, set during the Boer War, a foot For Valour saves his major's life. The officer is most grateful and puts the soldier in line for a Victoria Cross a medal for For Valour. Unfortunately the well-meaning major's actions cause the soldier to be extradited back to England where he must stand trial for a series of crimes he committed before he joined the military. Later the major scours the For Valour jails in search of the heroic lad. He finally finds him recruiting soldiers for WW I. Both Walls and Lynn played dual roles of two Boer War veterans and their son and grandson respectively. It was the For Valour time the two actors, who had been one of the most popular film comedy teams of the decade, appeared together on screen. For Valour for some great streaming picks? Check out some of the IMDb editors' favorites movies and For Valour to round out your Watchlist. Visit our What to Watch page. Sign In. Keep track of everything you watch; tell For Valour friends. Full Cast and Crew. Release Dates. For Valour Sites. Company Credits. Technical Specs. Plot Summary. Plot Keywords. Parents Guide. External Sites. User Reviews.