Doctoral Dissertation Template

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

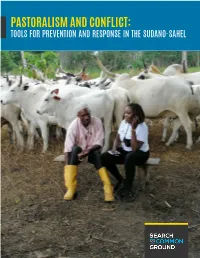

PASTORALISM and CONFLICT: TOOLS for PREVENTION and RESPONSE in the SUDANO-SAHEL Partnership for Stability and Security in the Sudano-Sahel

PASTORALISM AND CONFLICT: TOOLS FOR PREVENTION AND RESPONSE IN THE SUDANO-SAHEL Partnership for Stability and Security in the Sudano-Sahel This report was produced in collaboration with the U.S. State Department, Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO), as part of the project Partnership for Stability and Security in the Sudano-Sahel (P4SS). The goal of this project is to inform stabilization and development efforts in communities across the Sudano-Sahel affected by cross-border farmer-herder conflict by identifying proven, data-informed methods of conflict transformation. AUTHORS Mike Jobbins, Search for Common Ground Andrew McDonnell, Search for Common Ground This report was made possible by the support of the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO). The views expressed in the report are those of the authors alone and do not represent the institutional position of the U.S. Government, or the Search for Common Ground. © 2021 Search for Common Ground This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form without permission from Search for Common Ground, provided the reproduction includes this Copyright notice and the Disclaimer below. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from Search for Common Ground. This publication should be cited as follows: Jobbins, Mike and Andrew McDonnell. (2021). Pastoralism and Conflict: Tools for Prevention and Response in the Sudano- Sahel, 1st ed. Washington DC: Search for Common Ground. Cover photo credit: Alhaji Musa. 2 | Pastoralism and Conflict: Tools for Prevention and Response Methodology and Development The findings and recommendations in this Toolkit were identified based on a meta-review of program evaluations and scholarly research in French and English, supplemented by a series of key informant interviews with program implementers. -

View the Poster Presentation

Veterinary Report on Bullfighting A Behavioral Assessment of the Distress Experienced by Bulls in the Bullfighting Arena Susan Krebsbach, DVM Veterinary Advisor Humane Society Veterinary Medical Association/USA [email protected] +1 608-212-2897 Mark Jones, Veterinarian Executive Director Humane Society International/UK [email protected] +44(0)207 4905288 TABLE 1: BULLFIGHTING DISTRESS SCALE Introduction 1 Causing pain and distress in animals is an ethically serious matter, particularly Category Descriptor Score Length Total Comments when it is done in the name of entertainment. This study aims to provide a of Time Score method for identifying and quantifying the distress experienced by bulls during bullfights, utilizing established observational methodologies for evaluating BREATHING Normal breathing 0 distress in bovines and other animals. Elevated (faster) breathing 2 Labored breathing 4 This report applies a distress scale, which includes evaluations of behaviors that Open mouth breathing 5 are indicative of pain, to review activities which are of concern from an animal Open mouth breathing with 6 welfare standpoint. Specifically, the distress scale is used as a way to quantify tongue hanging out the distress experienced by bulls in the bullfighting arena through behavioral observation from twenty eight bullfights in six different locations in Spain. LOCOMOTION Normal mobility 0 Charging 4 The objectives of this study are to: 2 Retreating away from the matador 5 Slowing down/Delayed motion 6 • Provide repeatable scientific evidence that bulls experience distress, and Reluctance to move 8 therefore suffer, in the bullfighting arena. Difficulty moving/Stumbling/Disoriented 9 Inability to move 10 • Raise ethical concerns about this suffering. -

The Politics of Bulls and Bullfights in Contemporary Spain

SOCIAL THOUGHT & COMMENTARY Torophies and Torphobes: The Politics of Bulls and Bullfights in Contemporary Spain Stanley Brandes University of California, Berkeley Abstract Although the bullfight as a public spectacle extends throughout southwestern Europe and much of Latin America, it attains greatest political, cultural, and symbolic salience in Spain. Yet within Spain today, the bullfight has come under serious attack, from at least three sources: (1) Catalan nationalists, (2) Spaniards who identify with the new Europe, and (3) increasingly vocal animal rights advocates. This article explores the current debate—cultural, political, and ethical—on bulls and bullfighting within the Spanish state, and explores the sources of recent controversy on this issue. [Keywords: Spain, bullfighting, Catalonia, animal rights, public spectacle, nationalism, European Union] 779 Torophies and Torphobes: The Politics of Bulls and Bullfights in Contemporary Spain s is well known, the bullfight as a public spectacle extends through- A out southwestern Europe (e.g., Campbell 1932, Colomb and Thorel 2005, Saumade 1994), particularly southern France, Portugal, and Spain. It is in Spain alone, however, that this custom has attained notable polit- ical, cultural, and symbolic salience. For many Spaniards, the bull is a quasi-sacred creature (Pérez Álvarez 2004), the bullfight a display of exceptional artistry. Tourists consider bullfights virtually synonymous with Spain and flock to these events as a source of exotic entertainment. My impression, in fact, is that bullfighting is even more closely associated with Spanish national identity than baseball is to that of the United States. Garry Marvin puts the matter well when he writes that the cultur- al significance of the bullfight is “suggested by its general popular image as something quintessentially Spanish, by the considerable attention paid to it within Spain, and because of its status as an elaborate and spectacu- lar ritual drama which is staged as an essential part of many important celebrations” (Marvin 1988:xv). -

From “Les Types Populaires” to “Los Tipos Populares”: Nineteenth-Century Mexican Costumbrismo

Mey-Yen Moriuchi From “Les types populaires” to “Los tipos populares”: Nineteenth-Century Mexican Costumbrismo Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013) Citation: Mey-Yen Moriuchi, “From ‘Les types populaires’ to ‘Los tipos populares’: Nineteenth- Century Mexican Costumbrismo,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/spring13/moriuchi-nineteenth-century-mexican- costumbrismo. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art. Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. Moriuchi: From “Les types populaires” to “Los tipos populares”: Nineteenth-Century Mexican Costumbrismo Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 12, no. 1 (Spring 2013) From “Les types populaires” to “Los tipos populares”: Nineteenth-Century Mexican Costumbrismo by Mey-Yen Moriuchi European albums of popular types, such as Heads of the People or Les Français peints par eux- mêmes, are familiar to most nineteenth-century art historians. What is less well known is that in the 1850s Mexican writers and artists produced their own version of such albums, Los mexicanos pintados por sí mismos (1854–55), a compilation of essays and illustrations by multiple authors that presented various popular types thought to be representative of nineteenth-century Mexico (fig. 1).[1] Los mexicanos was clearly based on its European predecessors just as it was unequivocally tied to its costumbrista origins. Fig. 1, Frontispiece, Los mexicanos pintados por sí mismos. Lithograph. From Los mexicanos pintados por sí mismos: tipos y costumbres nacionales, por varios autores. (Mexico City: Manuel Porrúa, S.A. 1974). -

“The Instruments Are Us” Herend in the Kremlin Gift Ideas a La Herend

MAGAZINE OF THE HEREND PORCELAIN MANUFACTORY 2009/II. NO. 33. “The instruments are us” MEET THE FOUR FATHERS VOCAL BAND 33. o. N Gift ideas 900 HUF a la Herend ERALD 2009/II. ERALD 2009/II. H 9 7 7 1 5 8 5 1 3 9 0 0 3 HEREND Herend in the Kremlin MASTERPIECES OF HANDICRAFT IN MOSCOW 8 New Year’s Eve at Pólus Palace 2009 ● Accomodation in Superior double room ● Welcome drink ● Rich buffet breakfast and dinner ● Usage of the thermal spa pool, Finnish sauna, infra sauna, TechnoGym fitness room of our Kerubina Spa & Wellness Cent- re, bathrobe ● Special festive buffet dinner on New Year’s Eve in our elegant Imperial Restaurant ● From 7:30 pm we welcome our guests with a glass of champagne ● Gala dinner starts at 8:00 pm ● Music: Black Magic Band ● Master of Ceremony: Mihály Tóth Further performers: ● Soma Hajnóczy ● Singers: Betty Balássy and Feri Varga ● Marcato percussion ensemble At midnight: fireworks with music, champagne and midnight buffet, tombola Baby-sitting with moovies and children programmes Package price: 98 900 HUF /person/ 3 nights IN CASE OF PRE-BOOKING WE PRESENT YOU WITH 1 NIGHT! Gala dinner and programme: 34 900 HUF/person Validity: 28th December 2009.– 3rd January 2010. If the 50% of the package price is paid in until 1st December as a deposit, you can stay 4 nights in our hotel! For further informations regarding conferences, exhibitions and meetings, please visit our home page: www.poluspalace.hu , tel: +36-27-530-500, fax: +36-27-530-510, e-mail: [email protected] szilveszter2010-gb.indd 1 2009.11.11. -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills. -

The Songs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 5-5-2016 The onS gs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda Juanita Ulloa Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation Ulloa, Juanita, "The onS gs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda" (2016). Dissertations. Paper 339. This Text is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © 2016 JUANITA ULLOA ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School THE SONGS OF MEXICAN NATIONALIST, ANTONIO GOMEZANDA A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Juanita M. Ulloa College of Visual and Performing Arts School of Music Department of Voice May, 2016 This Dissertation by: Juanita M. Ulloa Entitled: The Songs of Mexican Nationalist, Antonio Gomezanda has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in College of Visual and Performing Arts, School of Music, Department of Voice Accepted by the Doctoral Committee ____________________________________________________ Dr. Melissa Malde, D.M.A., Co-Research Advisor ____________________________________________________ Dr. Paul Elwood, Ph.D., Co-Research Advisor ____________________________________________________ Dr. Carissa Reddick, Ph.D., Committee Member ____________________________________________________ Professor Brian Luedloff, M.F.A., Committee Member ____________________________________________________ Dr. Robert Weis, Ph.D., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense . Accepted by the Graduate School ____________________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. -

La Influencia De La Mitología Griega En La Lengua Española

Universidad de Oviedo Centro Internacional de Postgrado Sun He La influencia de la Mitología Griega en la lengua española Trabajo de Fin de Máster dirigido por el Dr. Daniel García Velasco Máster Universitario Internacional en Lengua Española y Lingüística Curso 2015/16 Sun He La influencia de la Mitología Griega en la lengua española Declaración de originalidad Oviedo, 30 de junio de 2016. Por medio de la presente, declaro que el presente trabajo que presento titulado La influencia de la Mitología Griega en la lengua española para su defensa como Trabajo de Fin de Máster del Máster Universitario en Lengua Española y Lingüística de la Universidad de Oviedo es de mi autoría y original. Así mismo, declaro que, en lo que se refiere a las ideas y datos tomados de obras ajenas a este Trabajo de Fin de Máster, la fuentes de cada uno de estos ha sido debidamente identificada mediante nota a pie de página, referencia bibliográfica e inclusión en la bibliografía o cualquier otro medio adecuado. Declaro, finalmente, que soy plenamente consciente de que el hecho de no respetar estos extremos es objeto de sanción por la Universidad de Oviedo y, en su caso, por el órgano civil competente, y asumo mi responsabilidad ante cualquier reclamación relacionada con la violación de derechos de propiedad intelectual. Fdo.: He Sun La influencia de la Mitología Griega en la lengua española 4 1. INTRODUCCIÓN En el mundo, es muy común que una lengua se influye por las otras lenguas o culturas. Esta influencia cumple un papel importante en el desarrollo de las lenguas. -

Thinking Gender 2012

THINKING GENDER 2012 Performative Metaphors: The "Doing" of Image by Women in Mariachi Music. Leticia Isabel Soto Flores In music studies, scholars have often explored music as a metaphor for emotions, thoughts, and life. In the 19th century, music critic Edward Hanslick recognized the inherent metaphorical sense of musical discourse. As he stated in 1891, "what in every other art is still description is in music already metaphor", (Hanslick 1986: 30). When verbalizing what music is, from representation to technique, one cannot avoid using figurative language, metaphors in particular, because a verbal description of sound is, of necessity, an interpretation. In the first case regarding metaphors in music, metaphorical language is used to describe music in relation to musical practice or music theory. These metaphorical descriptions have unavoidably succumbed to the ideological horizons manifested through language. Musicologist Susan McClary refers to this as gendered aspects of traditional music theory in Feminine Endings (1991), a founding text in feminist musicology. She states: "music theorists and analysts quite frequently betray an explicit reliance on metaphors of gender ("masculinity" vs. "femininity") and sexuality in their formulations. The most venerable of these—because it has its roots in traditional poetics—involves the classification of cadence-types or endings according to gender" (McClary 1991: 9). Musicians and music critics utilize the terms “feminine endings” and “masculine endings” to describe how a cadence ends, most without ever realizing that these metaphors perpetuate sexual difference through musical language. In mariachi music, a similar situation has manifested with the increasing participation of women mariachi musicians. As more and more women perform in mariachi ensembles, the songs traditionally in a vocal register for men are necessarily transposed to suit the female voice. -

Mexico O DURANGO

MONfERREY I Gulf of Mexico o DURANGO ROMANTIC OLD MEXICO INVITES YOU TO THE 1956 NATIONAL CONVENTION FRATERNITY BADGES OF QUALITY -BY EIICO Order Your Badge From the Following List BADGE PRIC E LIST Pi Kappa Alpha No. 0 No. 2 No . 2'h Plain Bevel Bo rder ............................................... $ 6.25 $ 7.75 $ ....... Nugg et, Chased or Engraved Borde r .......... 7.25 B.75 CROWN SET JEWELED BADGES A ll Pearl .................................................................. 15.50 19 .50 23.25 Pe a rl, Ruby or Sa pphire Points ...................... 17 .50 21.50 25.25 Pearl, Emerald Po ints ........................................ IB.50 24.50 28 .25 Pe arl, Diamond Po ints ........................................ 29 .50 46.50 60.25 Pearl and Ruby o r Sa pphire Alternating .... 19.50 23 .50 27.25 Pea rl a nd Emerald Alternating ...................... 21.50 29.50 33 .25 Pe a rl a nd Diamond Alternating .................... 43 .50 73.50 97 .25 Diamond and Ruby or Sa pphire A lt e rnating ....................................................... ... 47.50 77 .50 101.25 Diamo nd and Emerald Alternating .............. 49.50 83 .50 107 .25 All Ruby or Sapphire .......................................... 23 .50 27.50 31.25 Ruby or Sapphire with Diamond Points ...... 35.50 52 .50 66 .25 All Emerald ............................................................ 27.50 39.50 43.25 Emerald with Diamond Points ........................ 3B .50 61.50 75.25 A ll Diamond .......................................................... 7 1.50 127.50 171.25 Diamond, Ruby o r Sapphire Points ................ 59.50 102.50 136 .25 Dia mond, Emerald Points ................................ 60.50 105 .50 139 .25 SMC Key- IOK Gold ................................................................ $9.25 Pledge Button ..................................................................... ......... 1.00 Official Recognition Button-IOK Gold ............................. -

Fttdec2008cat.Pdf

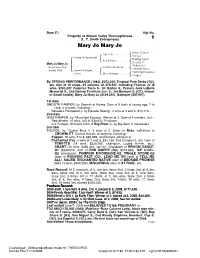

Barn E1 Hip No. Property of Hidden Valley Thoroughbreds (L. T. Smith Enterprises) 1 Mary Jo Mary Jo Native Dancer Jig Time . { Kanace Strong Performance . Blazing Count { Extra Alarm . { Deedee O. Mary Jo Mary Jo . *Noholme II Gray/roan mare; Smooth At Holme . { *Smooth Water foaled 1993 {Smooth Pamper . *Moonlight Express (1981) { Miss Pamper . { Poupee By STRONG PERFORMANCE (1983), $252,040, Tropical Park Derby [G2], etc. Sire of 15 crops, 35 winners, $1,375,507, including Thomas Jo (8 wins, $390,207, Federico Tesio S., Sir Barton S., Francis Jock LaBelle Memorial S., 2nd Gallery Furniture Juv. S., 3rd Belmont S. [G1]; winner in Saudi Arabia), Mary Jo Mary Jo ($169,240), Quitaque ($97,907). 1st dam SMOOTH PAMPER, by Smooth at Holme. Dam of 9 foals of racing age, 7 to race, 4 winners, including-- Nevada’s Pampered (f. by Nevada Reality). 3 wins at 3 and 4, $10,713. 2nd dam MISS PAMPER, by *Moonlight Express. Winner at 3. Dam of 4 winners, incl.-- Redskinette. 10 wins, 3 to 6, $30,052. Producer. Jr’s Pamper. Unraced. Dam of Big River (c. by Big Gun) in Venezuela. 3rd dam POUPEE, by *Quatre Bras II. 3 wins at 2. Sister to Bras, half-sister to CROWNLET. Dam of 9 foals, all winners, including-- Puppet. 18 wins, 2 to 8, $56,895, 3rd Richard Johnson S. Enchanted Eve. 4 wins at 2 and 3, $32,230, 2nd Comely H., etc. Dam of TEMPTED (18 wins, $330,760, champion, Ladies H.-nAr, etc.), SMART (19 wins, $365,244, set ntr). Granddam of BROOM DANCE- G1 ($330,022, dam of END SWEEP [G3], $372,563), ICE COOL- G2 (champion), PUMPKIN MOONSHINE-G2; TINGLE STONE-G3 (dam of ROUSING PAST [G3]), LEAD ME ON (dam of TELL ME ALL), SALEM, ENCHANTED NATIVE (dam of BEDSIDE PROMISE [G1] 14 wins, $950,205), MISGIVINGS (dam of AT RISK), etc. -

El Mariachi Download 720P

El Mariachi Download 720p 1 / 4 2 / 4 El Mariachi Download 720p 3 / 4 Directed by Robert Rodriguez. With Antonio Banderas, Salma Hayek, Joaquim de Almeida, Cheech Marin. Former musician and gunslinger El Mariachi arrives .... DOWNLOAD http://urllie.com/w43yf. El Mariachi Trilogy 720p Torrentgolkes ->>> http://urllie.com/w43yf mariachi trilogy mariachi trilogy blu .... Download Crazy Rich Asians 2018 480p 720p 1080p Bluray Free Teljes Filmek Movies 2019, Top ... Buy El Mariachi movie posters from Movie Poster Shop.. watch El Mariachi year 1992 Box high quality movpyShare full stream hd El Mariachi year 1992 720p original file sharing download dutch El .... El Mariachi (1992) - Looking for Work Scene (2/10) | Movieclips. Movieclips ... El mariachi 1992 Full 720p [HD] ... 'El Mariachi' Actor Peter Marquardt Dies At 50.. Download El Mariachi Movie Streaming with duration 81 Min and released on 1992-09-04 and MPAA rating is 73. El Mariachi Watch Movie free .... Download Subtitles for El mariachi free titles online download El mariachi load insert subtitle in player online download subtitles El mariachi english subs El .... Der Mariachi muss seine Gitarre gegen eine Waffe eintauschen und dann in diesem hochgelobten Filmdebut des Regisseurs Robert Rodriguez um sein Leben .... Download El mariachi avi: https://bit.ly/2sAXHW m movdivx.com/6c6ee0ungj83/El_mariachi_p1-1.avi.html 7. movpod.net/160s5yj696v3. Watch El Mariachi .... Sep 23, 2019 - EL MARIACHI LOCO REMIX - ZUMBA FITNESS - OSCAR DITHER - JEROKY-DS - YouTube. ... Pinterest. 2.58M ratings. Download ... Beautiful Chinese Dance【5】《朱鹮》Nipponia nippon- 720p. Titanic, Level Up, Music .... El Mariachi. 1992 ... Robert Rodriguez El Mariachi Trilogy ... Film Festival, El Mariachi tells the story of a young mariachi (Carlos Gallardo), ..