THE MEDIUM and MCLUHAN's MESSAGE Lance Strate1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

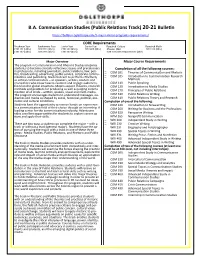

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin

B.A. Communication Studies (Public Relations Track) 20-21 Bulletin https://bulletin.oglethorpe.edu/9-major-minor-programs-requirements/ CORE Requirements Freshman Year Sophomore Year Junior Year Senior Year Required Culture Required Math COR 101 ( 4hrs) COR 201 ( 4hrs) COR 301 (4hrs) COR 400 (4hrs) Choose One: COR 314 (4hrs) COR 102 ( 4hrs) COR 202 ( 4hrs) COR 302 (4hrs) COR 103/COR 104/COR 105 (4hrs) Major Overview Major Course Requirements The program in Communication and Rhetoric Studies prepares students to become critically reflective citizens and practitioners Completion of all the following courses: in professions, including journalism, public relations, law, poli- COM 101 Theories of Communication and Rhetoric tics, broadcasting, advertising, public service, corporate commu- nications and publishing. Students learn to perform effectively COM 105 Introduction to Communication Research as ethical communicators – as speakers, writers, readers and Methods researchers who know how to examine and engage audiences, COM 110 Public Speaking from local to global situations. Majors acquire theories, research COM 120 Introduction to Media Studies methods and practices for producing as well as judging commu- COM 270 Principles of Public Relations nication of all kinds – written, spoken, visual and multi-media. The program encourages students to understand messages, au- COM 310 Public Relations Writing diences and media as shaped by social, historical, political, eco- COM 410 Public Relations Theory and Research nomic and cultural conditions. Completion of one of the following: Students have the opportunity to receive hands-on experience COM 240 Introduction to Newswriting in a communication field of their choice through an internship. A COM 260 Writing for Business and the Professions leading center for the communications industry, Atlanta pro- vides excellent opportunities for students to explore career op- COM 320 Persuasive Writing tions and apply their skills. -

Digital Media Practice and Medium Theory Informing Learning on Mobile Touch Screen Devices

Touching knowledge: Digital media practice and medium theory informing learning on mobile touch screen devices Victor Alexander Renolds Bachelor of Communications (Interactive Multimedia) College of Arts & Education Victoria University. Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts 13 November 2017 Abstract The years since 2007 have seen the worldwide uptake of a new type of mobile computing device with a touch screen interface. While this context presents accessible and low cost opportunities to extend the reach of higher education, there is little understanding of how learning occurs when people interact with these devices in their everyday lives. Medium theory concerns the study of one type of media and its unique effects on people and culture (Meyrowitz, 2001, p. 10). My original contribution to knowledge is to use medium theory to examine the effects of the mobile touch screen device (MTSD) on the learning experiences and practices of adults. My research question is: What are the qualities of the MTSD medium that facilitate learning by practice? The aim of this thesis is to produce new knowledge towards enhancing higher education learning design involving MTSDs. The project involved a class of post-graduates studying communications theory who were asked to complete a written major assessment using their own MTSDs. Their assignment submissions form the qualitative data that was collected and analysed, supplemented with field notes capturing my own post-graduate learning experiences whilst using an MTSD. I predominantly focus on the ideas of Marshall McLuhan within the setting of medium theory as my theoretical framework. The methods I use are derived from McLuhan's Laws of the Media (1975), its phenomenological underpinnings and relevance to the concept of ‘flow' (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014b, p. -

Features of Media Multitasking Experiences

WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES Media Multitasking D2.3.3.6 Features of media multitasking experience s Authors: Maria Viitanen, Stina Westman, Teemu Kinnunen, Pirkko Oittinen Confidentiality: Consortium Date and status: August 31st , 2012, version 0.1 This work was supported by TEKES as part of the next Media programme of TIVIT (Finnish Strategic Centre for Science, Technology and Innovation in the field of ICT) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Version history: Version Date State Author(s) OR Remarks (draft/ /update/ final) Editor/Contributors 0.1 31 st August MV, SW, TK, PO Review version {Participants = all research organisations and companies involved in the making of the deliverable} Participants Name Organisation Maria Viitanen Aalto University Researchers Stina Westman Department of Media Teemu Kinnunen Technology Pirkko Oittinen next Media www.nextmedia.fi www.tivit.fi WP2 MEDIA MULTITASKING D2.3.3.6 FEATURES OF MEDIA MULTITASKING EXPERIENCES 1 (40) Next Media - a Tivit Programme Phase 3 (1.1.–31.12.2012) Executive Summary Media multitasking is gaining attention as a phenomenon affecting media consumption especially among younger generations. From both social and technical viewpoints it is an important shift in media use, affecting and providing opportunities for content providers, system designers and advertisers alike. Media multitasking may be divided into media multitasking which refers to using several media together and multitasking with media, which consists of combining non- media activities with media use. In this deliverable we review research on multitasking from various disciplines: cognitive psychology, education, human-computer interaction, information science, marketing, media and communication studies, and organizational studies. -

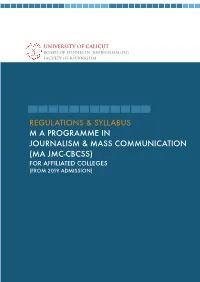

MA JMC CBCSS Syllabus 2019.Pages

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT ————————————————- BOARD OF STUDIES IN JOURNALISM (PG) FACULTY OF JOURNALISM REGULATIONS & SYLLABUS M A PROGRAMME IN JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION (MA JMC-CBCSS) FOR AFFILIATED COLLEGES (FROM 2019 ADMISSION) !1 UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT ————————————————- BOARD OF STUDIES IN JOURNALISM (PG) FACULTY OF JOURNALISM PROGRAMME REGULATIONS MASTER OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION (MA-JMC) CBCSS 2019 admission For AFFILIATED Colleges Title of the Programme affiliated Master of Arts in Journalism and Mass Communication ( MA JMC) Duration of the Programme Four semesters with each semester consisting of a minimum of 90 working days distributed over a minimum of 18 weeks, each of 5 working days Eligibility for Admission Candidates who have passed a Bachelor Degree course of the University of Calicut or any other university recognised by the University of Calicut as equivalent thereto and have secured a minimum of 50% marks in aggregate are eligible to apply. However, professional graduates will be considered for admission, provided they secure minimum of first class (60%) in overall subjects. Backward communities and SC/ST candidates will get relaxation in marks as per the university rules. Admission Procedure Admission to the program shall be made in the order of merit of performance of eligible candidates at the entrance examination. The entrance examination will assess the language ability, general knowledge and journalistic aptitude of the candidate. Weightage Marks Holders of PG diploma in journalism 5 marks Graduates with journalism sub 5 marks Three year degree holders with Journalism as Main 7 marks Bachelor’s Degree holders in Multimedia Communication / Visual Communication/ Film Production/Video Production 5 marks Candidates will be given weight age in only one of the categories whichever is higher. -

Politeness and Language Penelope Brown, Max Planck Institute of Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, the Netherlands

Politeness and Language Penelope Brown, Max Planck Institute of Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, The Netherlands Ó 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Abstract This article assesses the advantages and limitations of three different approaches to the analysis of politeness in language: politeness as social rules, politeness as adherence to an expanded set of Gricean Maxims, and politeness as strategic attention to ‘face.’ It argues that only the last can account for the observable commonalities in polite expressions across diverse languages and cultures, and positions the analysis of politeness as strategic attention to face in the modern context of attention to the evolutionary origins and nature of human cooperation. What Is Politeness? theoretical approach to the analysis of politeness in language can be distinguished. If, as many have claimed, language is the trait that most radi- 1. Politeness as social rules. To the layman, politeness is cally distinguishes Homo sapiens from other species, politeness a concept designating ‘proper’ social conduct, rules for is the feature of language use that most clearly reveals the speech and behavior stemming generally from high-status nature of human sociality as expressed in speech. Politeness individuals or groups. In literate societies such rules are is essentially a matter of taking into account the feelings of often formulated in etiquette books. These ‘emic’ (culture- others as to how they should be interactionally treated, specific) notions range from polite formulae like please and including behaving in a manner that demonstrates appropriate thank you, the forms of greetings and farewells, etc., to more concern for interactors’ social status and their social relation- elaborate routines for table manners, deportment in public, ship. -

“Meaning”: Philosophical Forebears and Linguistic Descendants

teorema Vol. XXVI/2, 2007, pp. 59-75 ISBN: 0210-1602 “Meaning”: Philosophical Forebears and Linguistic Descendants Siobhan Chapman RESUMEN Este artículo ofrece una visión general de las ideas que ayudaron a dar forma al pensamiento de Grice en “Meaning”, y considera también algunas de las respuestas más destacadas que dieron a Grice sus contemporáneos. Estos dos conjuntos de in- fluencias alimentaron el desarrollo de la teoría de la conversación de Grice, que ha te- nido un enorme impacto en el pensamiento posterior sobre el lenguaje en muchas áreas, particularmente en la disciplina lingüística conocida como “pragmática”. En las valoraciones de la obra de Grice, “Meaning” resulta a menudo ensombrecido por la teoría de la conversación, pero merece la pena volver sobre este artículo, ya que es el que establece los fundamentos generales de su filosofía del lenguaje. ABSTRACT This article offers an overview of some of the philosophical ideas that helped to shape Grice’s thinking in “Meaning”, and also considers some of the most salient re- sponses to “Meaning” from his contemporaries. These two sets of influences fed into the development of Grice’s theory of conversation, which has had an enormous im- pact on subsequent thinking about language in many areas, particularly in the linguis- tic discipline of pragmatics. “Meaning” is sometimes overshadowed by the theory of conversation in assessments of Grice’s work, but is worth revisiting because it sets out the foundations of his philosophy of language as a whole. I. INTRODUCTION Paul Grice’s “Meaning” is strikingly brief and deceptively simple- looking. At just twelve pages, it is the shortest of the five articles that appeared in volume 66 number 3 of The Philosophical Review. -

Origins of Human Communication

Origins of Human Communication Michael Tomasello A Bradford Book The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2008 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher. MIT Press books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For information, please e-mail [email protected] or write to Special Sales Department, The MIT Press, 55 Hayward Street, Cambridge, MA 02142. This book was set in Palatino by SNP Best-set Typesetter Ltd., Hong Kong, and was printed and bound in the United States. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tomasello, Michael. Origins of human communication / Michael Tomasello. p. cm.—(Jean Nicod lectures) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-262-20177-3 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Language and languages—Origin. 2. Animal communication. I. Title. P116.T66 2008 401—dc22 2007049249 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 A Focus on 1 Infrastructure What we call meaning must be connected with the primitive language of gestures. —Wittgenstein, The Big Typescript Walk up to any animal in a zoo and try to communicate something simple. Tell a lion, or a tiger, or a bear to turn its body like “this,” showing it what to do by demonstrat- ing with your hand or body and offering a delicious treat in return. Or simply point to where you would like it to stand or to where some hidden food is located. -

The Evolution of Human Communication and Language

CHAPTER 14 The evolution of human communication and language James R. Hurford 14.1 Introduction territorial songs, and by vervet monkey alarm calls. We are not yet sure exactly what is conveyed Human language stands out in a number of ways by whale songs, but a reasonable default hypoth- from the topics of almost all of the other chapters esis would seem to be that they convey messages of in this book. Although every communication sys- the same expressive power as complex birdsongs. tem can claim in some way to be unique, human We may be wrong about this, but the current belief language is spectacularly unique in its complexity is thus that any human language is capable of com- and expressive power. municating the sum total of all that any animal spe- Complexity is hard to measure, but a clue is cies can communicate, and more. More, because we given by the fact that The Cambridge Grammar of alone, as far as we know, can tell each other about the English Language (Huddleston & Pullum, 2002), ctional or abstract objects, and about events far which is just a description of Modern Standard distant in time and space. English, weighs in at over 1700 pages. The head- In the bulk of this chapter, I will list and discuss ings of the rst half-dozen descriptive chapters, some of the most important differences and simi- out of eighteen, are: The verb, The clause: comple- larities between human languages and nonhuman ments, Nouns and noun phrases, Adjectives and communication systems, with an evolutionary adverbs, Prepositions and preposition phrases, perspective, in particular drawing on results from and The clause: adjuncts. -

Communication Theory and the Disciplines JEFFERSON D

Communication Theory and the Disciplines JEFFERSON D. POOLEY Muhlenberg College, USA Communication theory, like the communication discipline itself, has a long history but a short past. “Communication” as an organized, self-conscious discipline dates to the 1950s in its earliest, US-based incarnation (though cognate fields like the German Zeitungswissenschaft (newspaper science) began decades earlier). The US field’s first readers and textbooks make frequent and weighty reference to “communication theory”—intellectual putty for a would-be discipline that was, at the time, a collage of media-related work from the existing social sciences. Soon the “communication theory” phrase was claimed by US speech and rhetoric scholars too, who in the 1960s started using the same disciplinary label (“communication”) as the social scientists across campus. “Communication theory” was already, in the organized field’s infancy, an unruly subject. By the time Wilbur Schramm (1954) mapped out the theory domain of the new dis- cipline he was trying to forge, however, other traditions had long grappled with the same fundamental questions—notably the entwined, millennia-old “fields” of philos- ophy, religion, and rhetoric (Peters, 1999). Even if mid-century US communication scholars imagined themselves as breaking with the past—and even if “communica- tion theory” is an anachronistic label for, say, Plato’s Phaedrus—no account of thinking about communication could honor the postwar discipline’s borders. Even those half- forgotten fields dismembered in the Western university’s late 19th-century discipline- building project (Philology, for example, or Political Economy)haddevelopedtheir own bodies of thought on the key communication questions. The same is true for the mainline disciplines—the ones we take as unquestionably legitimate,thoughmostwereformedjustafewdecadesbeforeSchramm’smarch through US journalism schools. -

Harold Innis and the Empire of Speed

Review of International Studies (1999), 25, 273–289 Copyright © British International Studies Association Harold Innis and the Empire of Speed RONALD J. DEIBERT* Abstract. Increasingly, International Relations (IR) theorists are drawing inspiration from a broad range of theorists outside the discipline. One thinks of the introduction of Antonio Gramsci’s writings to IR theorists by Robert Cox, for example, and the ‘school’ that has developed in its wake. Similarly, the works of Anthony Giddens, Michel Foucault, and Jurgen Habermas are all relatively familiar to most IR theorists not because of their writings on world politics per se, but because they were imported into the field by roving theorists. Many others of varying success could be cited as well. Such cross-disciplinary excursions are important because they inject vitality into a field that—in the opinion of some at least—is in need of rejuvenation in the face of contemporary changes. In this paper, I elaborate on the work of the Canadian communications theorist Harold Innis, situating his work within contemporary IR theory while underlining his historicism, holism, and attention to time- space biases. Introduction One of the more refreshing developments in recent International Relations (IR) theorizing has been the increasing willingness among scholars to step outside of traditional boundaries to draw from theorists not usually associated with the study of international relations.1 My own expeditions in this respect have been in the communications field, where I have drawn from an approach called ‘medium theory.’ Writers generally associated with this approach, such as Harold Innis, Marshall McLuhan, Eric Havelock, and Walter Ong, have analysed how different media of communications affect communication content, cognition, and the character of societies.2 In a recent study, I modified and reformulated medium theory to help * An earlier version of this article was delivered to the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, August 28–31, 1997, Washington, DC. -

Communication Models in Law1

T. Bekrycht: Communication Models in Law 157 COMMUNICATION MODELS IN LAW1 by TOMASZ BEKRYCHT* Communication processes can be generally described with the use of two models. The first one adopts cybernetic perspective, while the second one adopts social per- spective. Cybernetic perspective leads to transmission conception of communication whereas the social one to convergent concept of it. Both communication models are deeply present in the legal discourses, i.e. in lawmaking discourse and discourse of application. The issue related to the analysis of communication models in law is a part of a comprehensive area, which in the literature on the subject is related to the problem of ideology of lawmaking and law application. Dynamic nature of our social and legal reality can be described, on the one hand, by means of the conceptual network of communication models and, on the other hand, by means of many models of law- making and law application created by Jerzy Wróblewski and socio-historical model of lawmaking developed by Ewa Kustra based on the models of law set out in the conception of Phillipe Nonet and Phillip Selznick. The paper describes the position of the above-mentioned models in these discourses. KEYWORDS Modelling, discourse of lawmaking, discourse of law application, communication models 1. INTRODUCTION The issue related to the analysis of communication models in law is a part of a comprehensive area, which in the literature on the subject is related to 1 The following text was prepared as a part of a research grant financed by National Science Center (Poland), No. DEC-2012/05/B/HS5/01111. -

Philosophy of Language in the Twentieth Century Jason Stanley Rutgers University

Philosophy of Language in the Twentieth Century Jason Stanley Rutgers University In the Twentieth Century, Logic and Philosophy of Language are two of the few areas of philosophy in which philosophers made indisputable progress. For example, even now many of the foremost living ethicists present their theories as somewhat more explicit versions of the ideas of Kant, Mill, or Aristotle. In contrast, it would be patently absurd for a contemporary philosopher of language or logician to think of herself as working in the shadow of any figure who died before the Twentieth Century began. Advances in these disciplines make even the most unaccomplished of its practitioners vastly more sophisticated than Kant. There were previous periods in which the problems of language and logic were studied extensively (e.g. the medieval period). But from the perspective of the progress made in the last 120 years, previous work is at most a source of interesting data or occasional insight. All systematic theorizing about content that meets contemporary standards of rigor has been done subsequently. The advances Philosophy of Language has made in the Twentieth Century are of course the result of the remarkable progress made in logic. Few other philosophical disciplines gained as much from the developments in logic as the Philosophy of Language. In the course of presenting the first formal system in the Begriffsscrift , Gottlob Frege developed a formal language. Subsequently, logicians provided rigorous semantics for formal languages, in order to define truth in a model, and thereby characterize logical consequence. Such rigor was required in order to enable logicians to carry out semantic proofs about formal systems in a formal system, thereby providing semantics with the same benefits as increased formalization had provided for other branches of mathematics.