Union and Confession

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert D. Hawkins

LEX OR A NDI LEX CREDENDI THE CON F ESSION al INDI ff ERENCE TO AL TITUDE Robert D. Hawkins t astounds me that, in the twenty-two years I have shared Catholics, as the Ritualists were known, formed the Church Iresponsibility for the liturgical formation of seminarians, of England Protection Society (1859), renamed the English I have heard Lutherans invoke the terms “high church” Church Union (1860), to challenge the authority of English and “low church” as if they actually describe with clar- civil law to determine ecclesiastical and liturgical practice.1 ity ministerial positions regarding worship. It is assumed The Church Association (1865) was formed to prosecute in that I am “high church” because I teach worship and know civil court the “catholic innovations.” Five Anglo-Catholic how to fire up a censer. On occasion I hear acquaintances priests were jailed following the 1874 enactment of the mutter vituperatively about “low church” types, apparently Public Worship Regulation Act for refusing to abide by civil ecclesiological life forms not far removed from amoebae. court injunctions regarding liturgical practices. Such prac- On the other hand, a history of the South Carolina Synod tices included the use of altar crosses, candlesticks, stoles included a passing remark about liturgical matters which with embroidered crosses, bowing, genuflecting, or the use historically had been looked upon in the region with no lit- of the sign of the cross in blessing their congregations.2 tle suspicion. It was feared upon my appointment, I sense, For readers whose ecclesiological sense is formed by that my supposed “high churchmanship” would distract notions about the separation of church and state, such the seminarians from the rigors of pastoral ministry into prosecution seems mind-boggling, if not ludicrous. -

The Book of Concord FAQ God's Word

would be no objective way to make sure that there is faithful teaching and preaching of The Book of Concord FAQ God's Word. Everything would depend on each pastor's private opinions, subjective Confessional Lutherans for Christ’s Commission interpretations, and personal feelings, rather than on objective truth as set forth in the By permission of Rev. Paul T. McCain Lutheran Confessions. What is the Book of Concord? Do all Lutheran churches have the same view of the Book of Concord? The Book of Concord is a book published in 1580 that contains the Lutheran No. Many Lutheran churches in the world today have been thoroughly influenced by the Confessions. liberal theology that has taken over most so-called "mainline" Protestant denominations in North America and the large Protestant state churches in Europe, Scandinavia, and elsewhere. The foundation of much of modern theology is the view that the words of What are the Lutheran Confessions? the Bible are not actually God's words but merely human opinions and reflections of the The Lutheran Confessions are ten statements of faith that Lutherans use as official ex- personal feelings of those who wrote the words. Consequently, confessions that claim planations and summaries of what they believe, teach, and confess. They remain to this to be true explanations of God's Word are now regarded more as historically day the definitive standard of what Lutheranism is. conditioned human opinions, rather than as objective statements of truth. This would explain why some Lutheran churches enter into fellowship arrangements with What does Concord mean? non-Lutheran churches teaching things in direct conflict with the Holy Scriptures and the Concord means "harmony." The word is derived from two Latin words and is translated Lutheran Confessions. -

1 Crossing Bearing and Life in a Lutheran

Crossing Bearing and Life in a Lutheran Synod: What Can We Learn from Hermann Sasse? The Emmaus Conference Tacoma, Washington 1-2 May 2014 “The Lutheran Churches are still sunning themselves in the delusion that they have something to expect from the world other than the dear holy cross, which all those must carry who proclaim God’s Law and the Gospel of Jesus Christ to mankind. But this delusion will soon disappear”1 so wrote Hermann Sasse in March, 1949. While not exactly equivalent to synods in North American Lutheranism, Hermann Sasse 2(1895-1976) had his own experience with church governments as places for bearing the cross in Germany and later on in Australia. A son of a church of the Prussian Union, Sasse would become a member of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria, and eventually he would leave that body to immigrate to Australia where he would become a member of the United Evangelical Lutheran Church in Australia and then after that body’s merger with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Australia, the Lutheran Church of Australia. I propose that Sasse suggests not only a theology of the cross but an ecclesiology of the cross. As Udo Schnelle would put it: “The existence of the church itself is already an application of the theology of the cross.” 3Not long after re-locating to Australia, Sasse would write one of his “letters to Lutheran pastors” on the theologia crucis. This letter, a brilliant and concise introduction to Luther’s conceptuality of the theology of the cross; it also has ramifications for the theme of this paper, cross bearing in the life of a Lutheran Synod. -

![[Formula of Concord]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9966/formula-of-concord-1099966.webp)

[Formula of Concord]

[Formula of Concord] Editors‘ Introduction to the Formula of Concord Every movement has a period in which its adherents attempt to sort out and organize the fundamental principles on which the founder or founders of the movement had based its new paradigm and proposal for public life. This was true of the Lutheran Reformation. In the late 1520s one of Luther‘s early students, John Agricola, challenged first the conception of God‘s law expressed by Luther‘s close associate and colleague, Philip Melanchthon, and, a decade later, Luther‘s own doctrine of the law. This began the disputes over the proper interpretation of Luther‘s doctrinal legacy. In the 1530s and 1540s Melanchthon and a former Wittenberg colleague, Nicholas von Amsdorf, privately disagreed on the role of good works in salvation, the bondage or freedom of the human will in relationship to God‘s grace, the relationship of the Lutheran reform to the papacy, its relationship to government, and the real presence of Christ‘s body and blood in the Lord‘s Supper. The contention between the two foreshadowed a series of disputes that divided the followers of Luther and Melanchthon in the period after Luther‘s death, in which political developments in the empire fashioned an arena for these disputes. In the months after Luther‘s death on 18 February 1546, Emperor Charles V finally was able to marshal forces to attempt the imposition of his will on his defiant Lutheran subjects and to execute the Edict of Worms of 1521, which had outlawed Luther and his followers. -

Concordia Theological Quarterly

Concordia Theological Quarterly Inclusive Liturgical Language: Off-Ramp to Apostasy? Paul J. Grime Baptism and the Lord's Supper in John Charles A. Gieschen Once More to John 6 David P. Scaer The Bread of Life Discourse and Lord's Supper Jason M. Braaten The Doctrine of the Ministry in Salomon Glassius ArminWenz Defining Humanity in the Lutheran Confessions Roland F. Ziegler Natural Law and Same-Sex Marriage Scott Stiegemeyer US ISSN 0038-86 10 CTQ 78 (2014): 155-166 Theological Observer A Vision for Lutheranism in Central Europe [The following essay was first delivered as one of the Luther Academy Lectures for the occasion of the twentieth anniversary of the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in the Czech Republic at Saint Charles University in Prague on September 28,2013. The Editors.] Prague has been the location for many notable events and anniver saries over the past millennium. Many of these events, such as the Second Defenestration of Prague, led to the tragic events of the execution of the twenty-seven nobles and the beginning of the Thirty Years' War, both of which had a negative effect on the influence of Lutheranism in the world. On September 29, 2013, the Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in the Czech Republic observed the twentieth amriversary of its founding with a celebration at St. Michael's Church on the Feast of st. Michael and All Angels. The appointed readings for this particular feast demonstrate that the power of the devil, the world, and our sinful flesh are defeated not with might of arms but with the word of God alone. -

The Formula of Concord As a Model for Discourse in the Church

21st Conference of the International Lutheran Council Berlin, Germany August 27 – September 2, 2005 The Formula of Concord as a Model for Discourse in the Church Robert Kolb The appellation „Formula of Concord“ has designated the last of the symbolic or confessional writings of the Lutheran church almost from the time of its composition. This document was indeed a formulation aimed at bringing harmony to strife-ridden churches in the search for a proper expression of the faith that Luther had proclaimed and his colleagues and followers had confessed as a liberating message for both church and society fifty years earlier. This document is a formula, a written document that gives not even the slightest hint that it should be conveyed to human ears instead of human eyes. The Augsburg Confession had been written to be read: to the emperor, to the estates of the German nation, to the waiting crowds outside the hall of the diet in Augsburg. The Apology of the Augsburg Confession, it is quite clear from recent research,1 followed the oral form of judicial argument as Melanchthon presented his case for the Lutheran confession to a mythically yet neutral emperor; the Apology was created at the yet not carefully defined border between oral and written cultures. The Large Catechism reads like the sermons from which it was composed, and the Small Catechism reminds every reader that it was written to be recited and repeated aloud. The Formula of Concord as a „Binding Summary“ of Christian Teaching In contrast, the „Formula of Concord“ is written for readers, a carefully- crafted formulation for the theologians and educated lay people of German Lutheran churches to ponder and study. -

In the Lutheran Confessions: Dialogue Within the Reformation Spirit Oscar Cole-Arnal

Consensus Volume 7 | Issue 3 Article 1 7-1-1981 Concordia' and 'unitas' in the Lutheran confessions: dialogue within the Reformation spirit Oscar Cole-Arnal Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus Recommended Citation Cole-Arnal, Oscar (1981) "Concordia' and 'unitas' in the Lutheran confessions: dialogue within the Reformation spirit," Consensus: Vol. 7 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus/vol7/iss3/1 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Consensus by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CONCORDIA” AND “UNITAS” IN THE LUTHERAN CONFESSIONS Dialogue Within the Reformation Spirit Oscar L. Arnal Within the process of determining the criteria for fellowship among Canadian Lutherans, this symposium has been assigned the specific task of analyzing the re- lationship between concordia and unitas in the Lutheran Confessions. With that end in mind, I propose a comparison of two sets of our symbolic documents, namely the Augsburg Confession and the Book and Formula of Concord. By employing such a method, it is hoped that our historical roots may be utilized in the service of our re- sponsibility to critique and affirm each other. Before one can engage in this dialogue with the past, it becomes necessary to come to terms with our own presuppositions and initial assumptions. All our asser- tions, even our historical and doctrinal convictions, are rooted within the reality of our biological and sociological environments. We speak out of experiences which are our own both individually and collectively. -

Martin Luther's Concerns with the Numinous in the Lord's Supper Egil Grislis

Consensus Volume 30 Article 3 Issue 2 Festechrift: aF ith Elizabeth Rohrbough 11-1-2005 Martin Luther's concerns with the numinous in the Lord's Supper Egil Grislis Follow this and additional works at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus Recommended Citation Grislis, Egil (2005) "Martin Luther's concerns with the numinous in the Lord's Supper ," Consensus: Vol. 30 : Iss. 2 , Article 3. Available at: http://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus/vol30/iss2/3 This Articles is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Consensus by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 35 Martin Luther's Concerns With The Numinous In The Lord's Supper Egil Grislis The University of Manitoba The scholarly attention to Luther’s understanding of the real presence of Christ in the Lord’s Supper has been extensive. The early phase, up to 1520, while generally affirming the real presence, mainly addressed what Luther regarded as Roman Catholic aberrations. Subsequently Luther responded to the Swiss Reformed and German Anabaptist criticisms. Continuing to affirm the real presence, Luther elaborated several key motifs, such as the personal presence of Christ, the idea of testament and promise, the existential need for trust and for courage, the significance of love and faith. In the course of time, these motifs have received a detailed attention. At the same time, the motif of the numinous1 has been rather neglected, namely Luther’s intense awareness of the holiness of God along with the awe, humility, and joy which envelops the authentic experience of faith in Jesus Christ. -

Justification in Article III of the Formula of Concord

Concordia Seminary - Saint Louis Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary Bachelor of Divinity Concordia Seminary Scholarship 5-1-1944 Justification in Article III of the Formula of Concord John Meyer Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.csl.edu/bdiv Part of the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, John, "Justification in Article III of the Formula of Concord" (1944). Bachelor of Divinity. 108. https://scholar.csl.edu/bdiv/108 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Concordia Seminary Scholarship at Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bachelor of Divinity by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Resources from Concordia Seminary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JUSTIFICATION IH ARTICLE I1I OP THE F'OlUI.ULi OF CONCORD A Thesis Pr9aanted to The Faculty or Concordia Som1nary Department or Systematic Theology I I I · In Partial Fulfillment of the Hequ1ramenta f'or the Degree Ba chalor or Divinity by John E. Meyer May 1944 Ap proved TABLE OF CONTENTS I.~~ Luther•a Doctr1ne ••••••••••••••.••••••••• l. II. Antithesis: Osiander ••••••••••••••••.•••••••••••• Q. III. Ant1thas1a to Ant1thea1s1 The Oaiandrian Contro- ,- .ve'J:y ........................................... 31. f..tu, IV. ~thesis: Formula of Concord •••••••••.••••••••• 42. B1bl1oBro.phy •..•••.•••....•.•••...•••.•••.•..•••••••• 50. I. Theaias Luther'• Doctrine John Andrew Quenstedt, the great Lutheran theologian, defined justification as "the external, judioi~, gracious act of the most Holy Trinity, by which a s1n1"ul man, whose . sins are forg iven, on account or the merit of Christ appre hended by faith, is . -

The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord

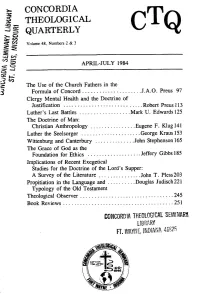

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 48. Numbers 2 & 3 APRIL-JULY 1984 The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord .....................J.A.O. Preus 97 Clergy Mental Health and the Doctrine of Justification ............................Robert Preus 1 13 Luther's Last Battles ..................Mark U. Edwards 125 The Doctrine of Man: Christian Anthropology ................Eugene F. Klug 14 1 Luther the Seelsorger .....................George Kraus 153 Wittenburg and Canterbury ............. .John Stephenson 165 The Grace of God as the Foundation for Ethics ....... ............Jeffery Gibbs 185 Implications of Recent Exegetical Studies for the Doctrine of the Lord's Supper: A Survey of the Literature ... ............John T. Pless 203 Propitiation in the Language and ..........Douglas Judisch 22 1 Typology of the Old Testament Theological Observer .................................245 Book Reviews .......................................251 The Use of the Church Fathers in the Formula of Concord J.A.O. Preus The use of the church fathers in the Formula of Concord reveals the attitude of the writers of the Formula to Scripture and to tradition. The citation of the church fathers by these theologians was not intended to override the great principle of Lutheranism, which was so succinctly stated in the Smalcalci Ar- ticles, "The Word of God shall establish articles of faith, and no one else, not even an angel" (11, 2.15). The writers of the Formula subscribed wholeheartedly to Luther's dictum. But it is also true that the writers of the Formula, as well as the writers of all the other Lutheran Confessions, that is, Luther and Melanchthon, did not look upon themselves as operating in a theological vacuum. -

The Lutheran Reformation's Formula of Concord

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 43, Number'4 JUNE 1979 Discord, Dialogue, and Concord: The Lutheran Reformation's Formula of Concord.... ;. Lewis W. Spitz 183 Higher Criticism and the Incarnation in The Thought of I.A. Dorner ......... John M. Ilrickamer I97 The Quranic Christ .................................... C. George Fry 207 Theological Observer ...........................................................222 Book Reviews .................................................................... 226 Books Received .................................................................... 250 Discord. Dialogue, and Concord: I83 Discord, Dialogue, and Concord The Lutheran Reformation's Formula of Concord Lewis W. Spitz The Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, observing the religious strife of the day, commented sardonically, "How absurd to try to m@e two men think alike on matters of religion, when I cannot make two timepieces agree!" Since his day the choris of religious belief and opinion has become increasingly cacaphonous, so that the celebration of the four hundredth anniversary of the Formu- la of Concord, a confession which restored a good measure of harmony to a strife-ridden segment of the church, is an event of deep significance. Commemorations of Protestant confessions have at times in the past been not merely devout, but also parti- san, sentimental, monumental, and even self-congratulatory or triumphalist, but ours must be done in a more reflective and analytical mood. The church of the Reformation, too, may bene- fit from reform and renewal. In the Ft-unkfurter gelehrten Anzeiger (1 772) Goethe mocked the iconoclastic zeal of the "en- lightened reformers" of his day, who were even urging the reform of Lutheranism. But, as Luther himself realized, such great things are not in the hands of man, but of God. -

A Bible Study on the Epitome

A BIBLE STUDY ON THE EPITOME THE BOOK OF CONCORD, SOLID DECARATION, PART I Taken in part from a study authored By Rev. Klemet Preus, by permission Introduction, Outline, additions, Chronology, Lessons 1, 2, 6, and Article I, V, & IX By Gene White Article IX by Rev. Doug Knoll, emeritus Where God’s Word is allowed His Spirit Works among His People ACKNOWLEDGMENT: The ACELC has agreed to host certain documents from Church Matters – Solutions because they support our mission and purpose as well as serve to further educate clergy and laity in orthodox Lutheran doctrine and practice. This 9 lesson study is one such document. Introduction This study uses by reference Concordia, the laymen’s version of the Book of Concord. Each member of the class should have their personal copy of the BOC, or some older version, to enhance their participation in this study. Note also that the Concordia has several prefaces, notations of historical significance, a glossary and graphics not found in the earlier versions. General note: There are page number differences between Version 1 and Version 2 of Concordia, the laymen’s version of the Book of Concord. It is not unrealistic for all Lutherans holding to the Lutheran Confessions to have this book in their personal library for future reference and study. If one is to judge what is happening in the church based on Holy Scripture and the Lutheran Confessions then is it necessary to have both documents in hand for such a task. Presentation For a Sunday morning approach take one or more Sundays for each lesson.