Working Papers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABS-Members-Book-2012.Pdf

Mission The mission of ABS is to serve the public interest as well as the needs of our clients by promoting the security of life and property and preserving the natural environment. ABS serves the marine, offshore and related industries as a self-regulatory organization for promoting the safety of life and property and protecting the environment at sea. Appropriate to this function, general management of ABS is vested in a membership comprising individuals eminent in these industries. From this membership a Council and special purpose committees are formed to provide the society with guidance and direction. The Board of Directors sets ABS policies and rule-making procedures. All committee members serve without remuneration. Administration of ABS CORPORatE OFFICERS Robert D. Somerville Linwood A. Pendexter Mark A. McGrath CHAIRMAN SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT & CHIEF SURVEYOR VICE PRESIDENT Christopher J. Wiernicki Peter Tang-Jensen Adam W. Moilanen PRESIDENT & CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT VICE PRESIDENT Tony Nassif T. Ray Bennett Richard D. Pride EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT & CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER VICE PRESIDENT VICE PRESIDENT & GREATER CHINA DIVISION PRESIDENT Jeffrey J. Weiner Robert W. Gilman Kenneth L. Richardson EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT & CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER VICE PRESIDENT & AMERICAS DIVISION PRESIDENT VICE PRESIDENT Robert A. Giuffra Jean C. Gould William J. Sember SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT VICE PRESIDENT VICE PRESIDENT Todd W. Grove Eric C. Kleess Kirsi Tikka SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT & CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER VICE PRESIDENT & PACIFIC DIVISION PRESIDENT VICE PRESIDENT & EUROPE DIVISION PRESIDENT Thomas A. Miller John P. McDonald SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, GENERAL COUNSEL & CORPORATE SECRETARY VICE PRESIDENT BOARD OF DIRECTORS Michael L. Carthew Dr. -

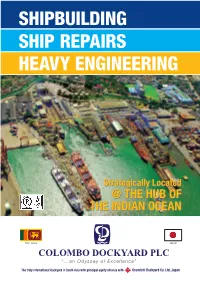

Ship Repairs Shipbuilding Heavy Engineering

SHIPBUILDING SHIP REPAIrs HEAVY ENGINEERING StrategicallyStrategically LocatedLocated @@ THETHE HUBHUB OFOF THETHE INDIANINDIAN OCEANOCEAN Sri Lanka Japan The truly international Dockyard in South Asia with principal equity alliance with Onomichi Dockyard Co. Ltd, Japan Our Core Values Quality Timeliness Safety Reliability Green Ethics Corporate Information Key Strengths Name : Colombo Dockyard PLC Strategic Location: Lying Operates 4 drydocks up to Combined Blasting and at the hub of Shipping lanes 125,000 DWT Painting Workshops with Legal Form : Public quoted company with limited liability joining West and East controlled conditions for A licensed enterprise of the Board of Investment of Sri Lanka Workforce of over 3,000 application of specialised Ship Repairs: Over 150 Sri Lankans protective coatings Registered Address & location : Port of Colombo, Sri Lanka vessels per annum generating US$ 30-40 million Average annual turnover over Certified to ISO 9001:2008 Established : 1974 US$ 150 million by Lloyds Register Quality Shipbuilding: 4 specialised Assurance State of the art Machinery and Partnership : Collaboration with Onomichi Dockyard Co., vessels per annum generating over US$ 100 million Equipment LRQA assessment assessors Ltd of Japan since 1993 have recommended the Heavy lifting capability up to Heavy Engineering: Heavy shipyard for OHSAS Major Shareholder : 51% by Onomichi Dockyard Co., Ltd, 160 Tons steel fabrication over US$ 10 18001:2007 & ISO 14001:2015 million per annum 500 Ton Steel Press certifications Over 40 years experience -

Excellence 40Years Of

Visit us at SMM - COLDOCK Stall Number B3.EG.205 T I M E S “...an Odyssey of Excellence” VOLUME 08 I SEPTEMBER 2014 www.cdl.lk 40CYearselebrating of Excellence The truly international Dockyard in South Asia with principal equity alliance with Onomichi Dockyard Co. Ltd, Japan. Colombo Dockyard was established in 1974 August 1, with the prime objective of providing ship repair facilities to the local industry requirements. The shipyard had evolved over the last four decades from a small time repair work shop to a full service ship repair facility acclaimed as an International shipyard competing with the best in the world. HIGHLIGHTSHIGHLIGHTS COLDOCK T I M E S INSIDE THIS ISSUE ... CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE 03 MANAGING DIRECTOR/CEO’S MESSAGE 04 CELEBRATING 40TH ANNIVERSARY OF COLOMBO DOCKYARD PLC 05 CONTAINER CARRIER “NIARA” MANAGED BY SEACHANGE MARITIME (S) PTE LTD REPAIRS COMPLETED SUCCESSFULLY 09 A HIGHLY COMPLEX MULTIPURPOSE PLATFORM COLOMBO DOCKYARD BUILT MV CORALS, SUPPLY VESSEL WAS RECENTLY DELIVERED TO HER THE FIRST OF TWO 400 PASSENGER VESSELS SINGAPOREAN OWNER FOR THE UNION TERRITORIES OF LAKSHADWEEP ADMINISTRATION OF THE GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 10 PRODUCT CARRIER “INTREPID REPUBLIC” MANAGED BY BERNHARD SCHULTE SHIPMANAGEMENT (CYPRUS) CO. LTD IN FOR DRYDOCK REPAIRS 12 MCLARENS SHIPPING LIMITED 13 A HIGHLY COMPLEX MULTIPURPOSE PLATFORM SUPPLY VESSEL WAS RECENTLY DELIVERED TO HER SINGAPOREAN OWNER 14 WARTSILA IN SRI LANKA 16 “PANGAEA” SUPER LUXURY YACHT CALLS COLOMBO FOR HER LAY UP REPAIRS JAPANESE COAST GUARD DELEGATION VISITS COLOMBO DOCKYARD 17 BULK CARRIER “JAL VAHINI” OWNED BY GLOBAL UNITED SHIPPING INDIA REPAIRS COMPLETED SUCCESSFULLY 18 “PANGAEA” SUPER LUXURY YACHT CALLS COLOMBO FOR HER LAY UP REPAIRS 19 PACIFIC INTERNATIONAL LINES (PIL), LOOKS TO COLOMBO AS A REPAIR HUB FOR THEIR VESSELS OPERATING IN THE REGION 20 DOCKYARD GENERAL ENGINEERING SERVICES 21 COLOMBO DOCKYARD BUILT MV CORALS, THE FIRST OF TWO COLOMBO ATTRACTS MULTIPURPOSE AND DIVING 400 PASSENGER VESSELS FOR THE UNION TERRITORIES OF SUPPORT VESSELS FOR MAJOR LAY UP REPAIRS. -

Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka: National Port Master Plan

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 50184-001 February 2020 Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka: National Port Master Plan (Financed by the Japan Fund for Poverty Reduction) The National Port Directions – Volume 1 (Part 7) Prepared by Maritime & Transport Business Solutions B.V. (MTBS) Rotterdam, The Netherlands For Sri Lanka Ports Authority This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Page left intentionally blank confidential National Port Directions | March 2019 Page 350 12 Navy 12.1 Introduction In this chapter the Navy is described in short. The Navy secures the nation by performing coast guard and providing port security. The following approach has been used for this chapter: • Paragraph 12.2 describes the current situation in Sri Lanka; • Paragraph 12.3 provides the recommendations. 12.2 Current situation The Navy has a presence in the port of Colombo, Galle and just outside of the port of Trincomalee. The de- facto functioning of the Sri Lankan Navy as coast guard make them important for the nation’s and port security. The navy actively performs the role for port security and is present at the gates of the port and with surveillance boats on the waters. Thus, close coordination with the Port Authority is essential. The navy reported shortage of mooring places in the port of Colombo especially in view of the ordered new larger vessels. -

Ship Repairs Shipbuilding Heavy

SHIPBUILDING SHIP REPAIRS HEAVY ENGINEERING StrategicallyStrategically LocatedLocated @@ THETHE HUBHUB OFOF THETHE INDIANINDIAN OCEANOCEAN Sri Lanka Japan The truly international Dockyard in South Asia with principal equity alliance with Onomichi Dockyard Co. Ltd, Japan Our Core Values Quality Timeliness Safety Reliability Green Ethics Corporate Information Key Strengths Name : Colombo Dockyard PLC Strategic Location: Lying Operates 4 drydocks up to Combined Blasting and at the hub of Shipping lanes 125,000 DWT Painting Workshops with Legal Form : Public quoted company with limited liability joining West and East controlled conditions for A licensed enterprise of the Board of Investment of Sri Lanka Workforce of over 3,000 application of specialised Ship Repairs: Over 150 Sri Lankans protective coatings Registered Address & location : Port of Colombo, Sri Lanka vessels per annum generating US$ 30-40 million Average annual turnover over Certified to ISO 9001:2015 Established : 1974 US$ 150 million by Lloyds Register Quality Shipbuilding: 4 specialised Assurance State of the art Machinery and Partnership : Collaboration with Onomichi Dockyard Co., vessels per annum generating over US$ 100 million Equipment LRQA Certification for OHSAS Ltd of Japan since 1993 18001:2007 & ISO 14001:2015 Heavy Engineering: Heavy Heavy lifting capability up to Major Shareholder : 51% by Onomichi Dockyard Co., Ltd, steel fabrication over US$ 10 160 Tons 150 Ton Self Propelled million per annum Transporter 500 Ton Steel Press Over 44 years experience in Aerial working platforms CNC Plasma Cutting Machines Ship Repair, Shipbuilding and Heavy Engineering Sectors The truly international Dockyard in South Asia with The Company principal equity alliance with Onomichi Dockyard Co. Ltd, Japan Colombo Dockyard PLC Colombo Dockyard PLC “...an Odyssey of Excellence” “...an Odyssey of Excellence” With over 4 decades of experience to our credit Colombo Dockyard has evolved into a formidable force in the regional shipbuilding arena. -

A Local Effort a Global Product

A LOCAL Annual Report EFFORT 2016 A GLOBAL PRODUCT 1 A LOCAL EFFORT A GLOBAL PRODUCT Not many companies can boast that their product makes a global impact but here at Colombo Dockyard, we create vessels that circle the world in more ways than one. Our hard work and attention to detail is on par with international standards and that’s why we remain at top of mind for many of our repeat as well as prospective clients. This year, we bring attention to our craftsmanship and ingenuity par excellence and highlight how our local effort creates an exceptional global product. “Yard No. NC-0230 a 450 Passenger ship built by Colombo Dockyard PLC for Government of India” Colombo Dockyard PLC 2 Annual Report 2016 Colombo Dockyard PLC Annual Report 2016 01 Contents Vision, Mission 03 Corporate Profile 04 Quality Policy, Environment Policy, Safety Policy 05 Financial Highlights 06 Chairman’s Review 07 Managing Director / CEO’s Review 09 Board of Directors 14 Key Management Profile 16 Financial Review 18 Corporate Governance 22 Risk Management 27 Shareholder Information 31 Financial Reports Financial Calender 2016/2017 35 Annual Report of the Board of Directors on the affairs of the Company 36 Related Party Transactions Review Committee Report 42 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 43 Chief Executive Officer’s and Chief Financial Officer’s Responsibility Statement 44 Independent Auditors’ Report 45 Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 46 Statement of Financial Position 47 Statement of Changes in Equity 48 Statement of Cash Flows 50 Notes to the Financial Statements 52 Ten Years Financial Summary 96 Notice of Annual General Meeting 97 Form of Proxy 99 Corporate Information Inner Back Cover Colombo Dockyard PLC 02 Annual Report 2016 Vision We pursue excellence and superior performance in all what we do to enhance the long-term interests of all our stakeholders in a socially responsible manner. -

Annual Report 2018

TRANSFORMATION AN ERA UNFOLDING Sri Lanka Insurance Corporation Ltd. Annual Report 2018 SLIC is moving along a trajectory of change and transformation anchored by a comprehensive three-year strategic plan. Across policy, process and infrastructure, we are evolving in step with the times and customer expectations, continuing to lay claim to our leadership positioning in the insurance industry. Sri Lanka Insurance Corporation Ltd. Annual Report 2018 1 CONTENTS SRI LANKA INSURANCE CORPORATION FINANCIAL REPORTS 4 – About this Report 104 – Annual Report of the Board of Directors of the Company 5 – About Sri Lanka Insurance Corporation 108 – Statement of Directors’ Responsibility 8 – Highlights 109 – Chief Financial Officer’s Statement of Responsibility 10 – Message from the Chairman 110 – Certificate of Actuary of the Insurer 12 – Managing Director’s Review 111 – Liability Adequacy Test 16 – Chief Executive Officer‘s Review 112 – Certificate of Incurred But Not (Enough) Reported Claims 113 – Independent Auditors’ Report STRATEGIC REPORT 116 – Statement of Financial Position 20 – Operating Environment 118 – Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income 22 – Strategy 120 – Statement of Changes in Equity 24 – Business Model 126 – Statement of Cash Flows 26 – Stakeholders 128 – Segmental Review: Statement of Income 28 – Materiality 130 – Segmental Review: Statement of Financial Position 132 – Notes to the Financial Statements MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS – Financial Capital 30 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 39 – Institutional Capital -

Sailing Ahead with Quality and Efficacy

Sailing Ahead with Quality and Efficacy Colombo Dockyard PLC | Annual Report - 2014 Vision We pursue excellence and superior performance in all what we do to enhance the long-term interests of all our stakeholders in a socially responsible manner. Mission We strive: To be the most competitive and viable business entity in South in Shipbuilding, Ship Repairs, Heavy Engineering and allied activities. To efficiently and effectively manage all our resources. To achieve sustainable growth. To enhance the interests of our Stakeholders, and thereby contribute to the pursuit of our vision. Contents Quality Policy 2 Environment Policy 2 Safety Policy 3 Corporate Profile4 Financial Highlights 6 Integrated Reporting Summary 7 Chairman’s Statement 8 Managing Director / CEO’s Review 12 Board of Directors 18 Key Management Profile20 Management Reports Management Discussion and Analysis 24 Financial Review 39 Corporate Governance 46 Risk Management 52 Corporate Milestones 56 The Operational Impact of 365 days 58 Shareholder Information 59 Sustainability Report 63 Financial Reports Annual Report of the Board of Directors on the Affairs of the Company 78 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 83 Chief Executive Officer’s and Chief Financial Officer’s Responsibility Statement84 Independent Auditor’s Report 85 Statement of Profit or Loss and Statement of Other Comprehensive Income86 Statement of Financial Position 87 Statement of Changes in Equity 88 Statement of Cash Flows 90 Notes to the Financial Statements 92 Ten Years Financial Summary 137 Notice of Annual General Meeting 138 Form of Proxy 139 Corporate Information Inner Back Cover Sailing Ahead with Quality and Efficacy For a period spanning 4 decades Colombo Dockyard PLC (CDPLC) has stood as a symbol and moniker of astounding quality and unparalleled excellence. -

1. Sri Lanka Has Maintained the Export-Oriented Development Strategy That Allowed It to Develop Some Dynamic Manufacturing Export Industries Over the Past Decades

Sri Lanka WT/TPR/S/237/Rev.1 Page 91 IV. TRADE POLICIES BY SECTOR (1) INTRODUCTION 1. Sri Lanka has maintained the export-oriented development strategy that allowed it to develop some dynamic manufacturing export industries over the past decades. No major trade liberalization or privatization measures have been introduced since its last Review. Likewise, the structure of the economy has not changed significantly since 2004. The services sector continues to be the largest contributor to GDP and employment; the share of the manufacturing sector in GDP has seen a slight decline, and that of agriculture has remained virtually unchanged, ending a long period of progressive decline. 2. Although its share in GDP stagnated during the review period (12.6% in 2009, at current prices), agriculture continues to play an important role in Sri Lanka's economy, as it provides the livelihood of a high percentage of the population, is an important foreign exchange earner, as well as a source of raw materials. Government intervention in agriculture, including border protection and domestic support, remains significant. Despite the provision of subsidies (e.g. subsidized inputs, price support, concessionary credit) and other types of assistance, productivity in domestic food crops has stagnated, and the country continues to be a net food importer. Tariff protection for agricultural products increased during the review period, and frequent changes in tariffs and ad hoc duty waivers have sometimes resulted in distortions in agricultural commodity markets and domestic production. The underlying structural factors that hold back the sector's growth include low levels of investment and credit, lack of quality inputs, inadequate transportation and marketing systems, lack of storage facilities, insufficient technological development, and land-use restrictions. -

Colombo Dockyard PLC Annual Report 2019

Colombo Dockyard PLC Annual Report 2019 Weathering the rough seas of macroeconomic upheavals and cloudy horizons of uncertainty, Colombo Dockyard PLC endured a stormy course in the year under review. Despite the storms however, with unwavering focus and resolute determination, key milestones were achieved: laying a new keel, completing 10,000 vessel repairs and building the 250th vessel - launching the ‘Make in Sri Lanka’ concept which proudly proclaims to the world that Colombo Dockyard is ready, willing and able to carve a name for itself in the global shipbuilding industry. Colombo Dockyard PLC approaches the new decade with hope, confidence and keen anticipation of new journeys in a bid to expand its horizons and charter new courses. 02 COLOMBO DOCKYARD PLC Annual Report 2019 CONTENTS Vision and Mission 03 Quality Policy, Health, Safety and Environmental Policy 03 Corporate Profile 04 Financial Highlights (Company) 05 The Operational Impact of 365 days 06 Chairman’s Review 08 Managing Director / CEO’s Review 11 Board of Directors 14 Corporate Management 17 Financial Review 20 Corporate Governance 24 Risk Management 29 Shareholder Information 33 Financial Report Financial Calender 2019/2020 37 Annual Report of the Board of Directors on the Affairs of the Company 38 Related Party Transactions Review Committee Report 43 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 44 Chief Executive Officer’s and Chief Financial Officer’s Responsibility Statement 45 Independent Auditors’ Report 46 Statement of Profit or Loss and Other Comprehensive Income -

Eagle Insurance Annual Report 2007

Annual Report 2007 Anchor of Trust Eagle Insurance PLC – Annual Report 2007 Our Vision To be a World-Class provider of Financial Solutions for Protection and Wealth Creation Our Mission We will be the most sought after Insurer and Fund Manager in Sri Lanka for security, return optimisation and excellence in service, achieving leadership in identified segments of the market Our Core Values Accepting risk with responsibility Being ethical Innovation Dedication to customers ® Designed & Produced by eMAGEWISE (Pvt) Ltd Encourage everyone to contribute and excel Photography by Taprobane Street Digital Plates by Imageline (Pvt) Ltd Printed by Printcare Corporate Information Name of the Company Eagle Insurance PLC Eagle profile Company Registration No - PQ 18 Legal Form Eagle Insurance took wing as a composite insurer • Public Company with limited liability. • Incorporated in Sri Lanka on 12th December 1986 under the within the Sri Lankan insurance landscape in the late Companies Act No. 17 of 1982. • Re-registered under the Companies Act No. 07 of 2007. 1980s. Over the years, the Company’s • A composite Insurance Company licensed by the Insurance Board of Sri Lanka. far-sightedness, good governance practices, ethics • The shares of the Company are listed on the Colombo Stock Exchange. Accounting Year and innovation have helped it to soar to new heights. 31st December Subsidiaries The dynamism and creativity of the Eagle family have Name of the Company Holding Principal Activity • Eagle NDB Fund Management been the engine of its evolution into a highly Company Limited 100% Fund Management • Rainbow Trust successful Company in the insurance and financial Management Limited 100% Trust Management and Administration services sector. -

Ship Repairs Shipbuilding Heavy Engineering

SHIPBUILDING SHIP REPAIRS HEAVY ENGINEERING StrategicallyStrategically LocatedLocated @@ THETHE HUBHUB OFOF THETHE INDIANINDIAN OCEANOCEAN Sri Lanka Japan The truly international Dockyard in South Asia with principal equity alliance with Onomichi Dockyard Co. Ltd, Japan Our Core Values Quality Timeliness Safety Reliability Green Ethics Corporate Information Key Strengths Name : Colombo Dockyard PLC Strategic Location: Lying Operates 4 drydocks up to Combined Blasting and at the hub of Shipping lanes 125,000 DWT Painting Workshops with Legal Form : Public quoted company with limited liability joining West and East controlled conditions for A licensed enterprise of the Board of Investment of Sri Lanka Workforce of over 3,000 application of specialised Ship Repairs: Over 150 Sri Lankans protective coatings Registered Address & location : Port of Colombo, Sri Lanka vessels per annum generating US$ 30-40 million Average annual turnover over Certified to ISO 9001:2015 Established : 1974 US$ 150 million by Lloyds Register Quality Shipbuilding: 4 specialised Assurance State of the art Machinery and Partnership : Collaboration with Onomichi Dockyard Co., vessels per annum generating over US$ 100 million Equipment LRQA Certification for OHSAS Ltd of Japan since 1993 18001:2007 & ISO 14001:2015 Heavy Engineering: Heavy Heavy lifting capability up to Major Shareholder : 51% by Onomichi Dockyard Co., Ltd, steel fabrication over US$ 10 160 Tons 150 Ton Self Propelled million per annum Transporter 500 Ton Steel Press Over 45 years experience in Aerial working platforms CNC Plasma Cutting Machines Ship Repair, Shipbuilding and Heavy Engineering Sectors The truly international Dockyard in South Asia with The Company principal equity alliance with Onomichi Dockyard Co. Ltd, Japan Colombo Dockyard PLC Colombo Dockyard PLC “...an Odyssey of Excellence” “...an Odyssey of Excellence” KDDI Cable Infinity is an ultra modern Cable Laying Vessel built by Colombo Dockyard for Kokusai Cable Ship Co.