Urban Regeneration in Moss Side, Manchester

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

111 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

111 bus time schedule & line map 111 Chorlton View In Website Mode The 111 bus line (Chorlton) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Chorlton: 5:56 AM - 11:43 PM (2) Piccadilly Gardens: 5:20 AM - 11:26 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 111 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 111 bus arriving. Direction: Chorlton 111 bus Time Schedule 34 stops Chorlton Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:13 AM - 11:08 PM Monday 5:56 AM - 11:43 PM Piccadilly Gardens Tuesday 5:56 AM - 11:43 PM Chinatown, Manchester City Centre Portland Street, Manchester Wednesday 5:56 AM - 11:43 PM Major Street, Manchester City Centre Thursday 5:56 AM - 11:43 PM Silver Street, Manchester Friday 5:56 AM - 11:43 PM India House, Manchester City Centre Saturday 6:48 AM - 11:43 PM Atwood Street, Manchester Oxford Road Station, Manchester City Centre Oxford Road, Manchester 111 bus Info Oxford House, Manchester City Centre Direction: Chorlton Stops: 34 Aquatics Centre, Chorlton upon Medlock Trip Duration: 35 min Line Summary: Piccadilly Gardens, Chinatown, University Shopping Centre, Chorlton upon Manchester City Centre, Major Street, Manchester Medlock City Centre, India House, Manchester City Centre, Tuer Street, Manchester Oxford Road Station, Manchester City Centre, Oxford House, Manchester City Centre, Aquatics Centre, University, Chorlton upon Medlock Chorlton upon Medlock, University Shopping Centre, Chorlton upon Medlock, University, Chorlton upon Royal Inƒrmary, Manchester Royal Inƒrmary Medlock, Royal Inƒrmary, -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Exploring the potential of complexity theory in urban regeneration processes. MOOBELA, Cletus. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20078/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20078/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Fines are charged at 50p per hour JMUQ06 V-l 0 9 MAR ?R06 tjpnO - -a. t REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10697385 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10697385 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Exploring the Potential of Complexity Theory in Urban Regeneration Processes Cletus Moobela A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The carrying out and completion of this research project was a stimulating experience for me in an area that I have come to develop an ever-increasing amount of personal interest. -

14-1676 Number One First Street

Getting to Number One First Street St Peter’s Square Metrolink Stop T Northbound trams towards Manchester city centre, T S E E K R IL T Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale S M Y O R K E Southbound trams towardsL Altrincham, East Didsbury, by public transport T D L E I A E S ST R T J M R T Eccles, Wythenshawe and Manchester Airport O E S R H E L A N T L G D A A Connections may be required P L T E O N N A Y L E S L T for further information visit www.tfgm.com S N R T E BO S O W S T E P E L T R M Additional bus services to destinations Deansgate-Castle field Metrolink Stop T A E T M N I W UL E E R N S BER E E E RY C G N THE AVENUE ST N C R T REE St Mary's N T N T TO T E O S throughout Greater Manchester are A Q A R E E S T P Post RC A K C G W Piccadilly Plaza M S 188 The W C U L E A I S Eastbound trams towards Manchester city centre, G B R N E R RA C N PARKER ST P A Manchester S ZE Office Church N D O C T T NN N I E available from Piccadilly Gardens U E O A Y H P R Y E SE E N O S College R N D T S I T WH N R S C E Ashton-under-Lyne, Bury, Oldham and Rochdale Y P T EP S A STR P U K T T S PEAK EET R Portico Library S C ET E E O E S T ONLY I F Alighting A R T HARDMAN QU LINCOLN SQ N & Gallery A ST R E D EE S Mercure D R ID N C SB T D Y stop only A E E WestboundS trams SQUAREtowards Altrincham, East Didsbury, STR R M EN Premier T EET E Oxford S Road Station E Hotel N T A R I L T E R HARD T E H O T L A MAN S E S T T NationalS ExpressT and otherA coach servicesO AT S Inn A T TRE WD ALBERT R B L G ET R S S H E T E L T Worsley – Eccles – -

41 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

41 bus time schedule & line map 41 Middleton - Sale Via Nmgh, Manchester, Mri View In Website Mode The 41 bus line (Middleton - Sale Via Nmgh, Manchester, Mri) has 5 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Higher Crumpsall: 6:08 AM - 6:25 PM (2) Manchester City Centre: 5:45 PM - 11:35 PM (3) Manchester City Centre: 11:05 PM (4) Middleton: 5:13 AM - 10:35 PM (5) Sale: 4:26 AM - 10:05 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 41 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 41 bus arriving. -

Hulme, Moss Side and Rusholme Neighbourhood Mosaic Profile

Hulme, Moss Side and Rusholme Neighbourhood Mosaic Profile Summary • There are just over 21,300 households in the Hulme, Moss Side and Rusholme Neighbourhood. • The neighbourhood contains a range of different household types clustered within different parts of the area. Moss Side is dominated by relatively deprived, transient single people renting low cost accommodation whereas Hulme and Rusholme wards contain larger concentrations of relatively affluent young people and students. • Over 60% of households in Moss Side contain people whose social circumstances suggest that they may need high or very high levels of support to help them manage their own health and prevent them becoming high users of acute healthcare services in the future. However, the proportion of households in the other parts of the neighbourhood estimated to require this levels of support is much lower. This reflects the distribution of different types of household within the locality as described above. Introduction This profile provides more detailed information about the people who live in different parts of the neighbourhood. It draws heavily on the insights that can be gained from the Mosaic population segmentation tool. What is Mosaic? Mosaic is a population segmentation tool that uses a range of data and analytical methods to provide insights into the lifestyles and behaviours of the public in order to help make more informed decisions. Over 850 million pieces of information across 450 different types of data are condensed using the latest analytical techniques to identify 15 summary groups and 66 detailed types that are easy to interpret and understand. Mosaic’s consistent segmentation can also provide a ‘common currency’ across partners within the city. -

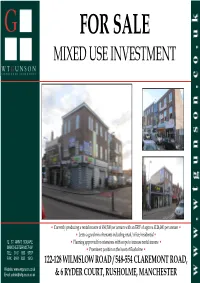

For Sale Mixed Use Investment

``` FOR SALE MIXED USE INVESTMENT • Currently producing a rental income of £96,500 per annum with an ERV of approx £126,000 per annum • • • Let to a good mix of tenants including retail/office/residential 12 ST ANN’S SQUARE • Planning approved for extensions with scope to increase rental income • MANCHESTER M2 7HW • Prominent position in the heart of Rusholme • TEL: 0161 833 9797 FAX: 0161 832 1913 122-128 WILMSLOW ROAD / 548-554 CLAREMONT ROAD, Website: www.wtgunson.co.uk Email: [email protected] & 6 RYDER COURT, RUSHOLME, MANCHESTER LOCATION The premises are situated in a prominent position on the “Curry Mile” at the junction of Wilmslow Road and Claremont Road in the heart of Rusholme, Manchester. Manchester City Centre is located approximately 2 miles north west of the property and is also situated within close proximity to Fallowfield, a highly popular student area. GENERAL DESCRIPTION The Property The property comprises a three storey row of terraced properties with a single storey unit adjoining. The units comprise of a mix of 6 x retail units, 1 office, 1 flat and 1 further office space over two floors which could be split. We understand planning permission is still valid for a two storey extension above the existing single storey property on the site 126-128 Wilmslow Road. Planning permission has also been granted for the erection of a two storey side extension on the site of 546 Claremont Road (A1) retail on the ground floor and offices (B1) above. Details of planning applications can be VAT provided upon request. -

From Manufacturing Industries to a Services Economy: the Emergence of a 'New Manchester' in the Nineteen Sixties

Introductory essay, Making Post-war Manchester: Visions of an Unmade City, May 2016 From Manufacturing Industries to a Services Economy: The Emergence of a ‘New Manchester’ in the Nineteen Sixties Martin Dodge, Department of Geography, University of Manchester Richard Brook, Manchester School of Architecture ‘Manchester is primarily an industrial city; it relies for its prosperity - more perhaps than any other town in the country - on full employment in local industries manufacturing for national and international markets.’ (Rowland Nicholas, 1945, City of Manchester Plan, p.97) ‘Between 1966 and 1972, one in three manual jobs in manufacturing were lost and one quarter of all factories and workshops closed. … Losses in manufacturing employment, however, were accompanied (although not replaced in the same numbers) by a growth in service occupations.’ (Alan Kidd, 2006, Manchester: A History, p.192) Economic Decline, Social Change, Demographic Shifts During the post-war decades Manchester went through the socially painful process of economic restructuring, switching from a labour market based primarily on manufacturing and engineering to one in which services sector employment dominated. While parts of Manchester’s economy were thriving from the late 1950s, having recovered from the deep austerity period after the War, with shipping trade into the docks at Salford buoyant and Trafford Park still a hive of activity, the ineluctable contraction of the cotton industry was a serious threat to the Manchester and regional textile economy. Despite efforts to stem the tide, the textile mills in 1 Manchester and especially in the surrounding satellite towns were closing with knock on effects on associated warehousing and distribution functions. -

Last Week's Collection Total £703 34P Thank You Sacrament of Marriage

Last week’s collection total £703 34p Thank you Sacrament of Marriage: 6 months’ notice must be given, please see Father to make arrangements, please speak to Clergy Marriage preparation course Book on line at marriage.stjosephsmanchester.co.uk: BURNAGE FOOD BANK; opening times are: Tuesday 12.30pm-2.30pm St Nicholas Church Hall, Kingsway, Burnage M19 1PL and Friday 3pm-5pm St Bernard's Church Hall, Burnage Lane, M19 1DR. www.burnagefoodbank.org.uk or tel: 07936698546. SOMETHING TO LOOK FORWARD TO!!!! IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF ST MARGARET CLITHEROW: Monday 2nd August to Wednesday 4th August, also visiting Harrogate and Thirsk. 1 single room available (£189) half board. HOLY ISLAND PILGRIMAGE, Friday 8th October to Sunday 10th October, half board in the Holiday Inn Hotel, visiting Ripon and Durham. One twin room available £189 per person.Contact Ann Tipper on442 5259 CARITAS SALFORD has teamed up with TERN (The Entrepreneurial Refugee Network) and Ben & Jerry’s (the well-known ice cream manufacturer) to launch the Ice Academy for the first time in Manchester. This is a project to support refugees in developing business ideas and starting their own business in Greater Manchester by connecting them to the experts, programmes and support they need to move forward. As a result, Caritas is searching for 15 volunteer ‘business buddies’ interested in social innovation and with some business/public sector experience or a professional services background. You will offer your expertise, guidance and advice as our entrepreneurs develop and test their business ideas. For more information and to express an interest, please contact Amir by email at [email protected] or call/text to 07477 926517. -

The Base, Manchester

Apartment 108 The Base, Worsley Street, Manchester, M15 4JP Two Bed Apartment Contact: The Base, Manchester t: 0161 710 2010 e: [email protected] or • Well-presented two bedroom apartment [email protected] • Located in the sought after Castlefield area Viewings: of Manchester City Centre Strictly by Appointment • Positioned on the first floor of the Base Landwood Group, South Central Development 11 Peter Street Manchester • Benefitting from two bathrooms, secured M2 5QR parking & balcony Date Particulars — March 2020 • Available with Vacant Possession Tenure Information The premises are held under a long leasehold title for a period of 125 years from 2003, under title number MAN60976. The annual service charge is £2045.76 per annum with the ground rent being £276.52 per annum. Tenancies Available with vacant possession. VAT All figures quoted are exclusive of VAT which may be applicable. Location Legal Each Party will be responsible for their own legal costs. The Base is located in the sought after Castlefield area of Manchester City centre. The area is extremely popular with young professionals and students due to its short Price distance from Manchester City Centre, next door to a £200,000. selection of bars and restaurants and it close proximity to the university buildings. EPC It has excellent road links into and around the city centre EPC rating D. and the Deansgate/Castlefield metrolink station is located approximately 5 minutes’ walk away. Important Notice Landwood Commercial (Manchester) Ltd for -

Wythenshawe, Market Place

Wythenshawe, Market Place • 360,000 sq ft of retail space • 88,000 sq ft of office space • 650,000 catchment population • 11,500 shopper population • Annual comparison goods turnover £23 million • 8 miles from Manchester City Centre • 2 miles from Manchester Airport • Within 1 mile of M56 / M62 New Metro Link Station 2016 RENT LOCATION £16,000 per annum exclusive. Wythenshawe Shopping Centre is extremely well located in the centre of Wythenshawe, a large suburb of south Manchester. The Centre is 8 RATES miles from Manchester city centre, 2 miles from Manchester airport and The information supplied by the Valuation Office Agency is as follows:- within one mile of the M56. The Centre serves a large local population and is easy to access by foot, car or public transport. The Centre is Rateable Value £23,000 already thriving with a large number of shoppers and is undergoing a rolling programme of refurbishment and redevelopment. Interested parties should verify this information with the local rating authority. A new ASDA superstore was opened in August 2007 in the heart of the Centre. New retailers for 2012 include Costa Coffee and JD Sports. SERVICE CHARGE Manchester city council have also taken representation in the scheme Details on application. bringing an additional 500 office workers to the scheme. VIEWING The subject property is positioned along Market Place and is positioned All viewings by prior appointment through this office. Contact Caren opposite the new Wilkinson’s unit. A street traders plan is attached Foster on 0121 643 9337. highlighting the units location for reference. CONTACT ACCOMMODATION Chris Gaskell Ground Floor Sales 122.95 m 2 1323 sq ft Email: [email protected] First Floor 112.83 m 2 1214 sq ft Or contact joint agents:- TENURE Tom Glynn - Colliers CRE The property is available by way of a new lease on effective FRI basis for [email protected] a term of years to be agreed. -

Wythenshawe, Haletop New Units

Wythenshawe, Haletop New Units • 360,000 sq ft of retail space • 88,000 sq ft of office space • 860,000 people in Wythenshawe • 11,000 shopper population • Annual comparison goods turnover £23 million • 8 miles from Manchester City Centre • 2 miles from Manchester Airport • Within 1 mile of M56 / M62 TIMING The properties will be available following completion of legal formalities and sub division works. LOCATION Wythenshawe Shopping Centre is extremely well located in the centre of RENT Wythenshawe, a large suburb of south Manchester. The Centre is 8 Unit 1 UNDER OFFER miles from Manchester city centre, 2 miles from Manchester airport and Unit 2 £24,500 per annum within one mile of the M56. The Centre serves a large local population Unit 3 £25,000 per annum and is easy to access by foot, car or public transport. The Centre is already thriving with a large number of shoppers and is undergoing a RATES rolling programme of refurbishment and redevelopment. The units will be reassessed following completion of development works. A new ASDA superstore was opened in August 2007 in the heart of the Centre. New retailers for 2012 include Wilkinson’s, Netto and Phones EPC 4U. Manchester city council have also taken representation in the An EPC will be available on completion of the construction works. scheme bringing an additional 500 office workers to site. Costa Coffee have also recently taken the unit alongside Store 21 shown on the SERVICE CHARGE attached street traders plan. The estimated service charge is based on £2.04 per sq ft overall. -

Hulme, Moss Side & Rusholme Neighbourhood Update 12

Hulme, Moss Side and Rusholme Neighbourhood update 12th June 2020 As a Neighbourhood we are working together to make sure that key information is shared, to support the people most at risk during this time. Click on the web links embedded below for further info. Please let me know if there’s any gaps in info needed at a Neighbourhood level, or any gaps or patterns that you are finding with the people you work with, or other relevant info to share. If you have concerns that someone may be most at risk, please contact: ● Care Navigator Service: self-referrals possible via email (referrals from organisations also by phone, 0300 303 9650); for people dealing with more complex issues; multi-agency approach. ● Be Well: referrals and social prescribing via any organisation & GPs; email or 0161-470 7120. ● Manchester City Council’s Community Response helpline: 0800 234 6123 or email. Mutual aid groups and volunteering ● Covid mutual aid groups are coordinating invaluable support at a local level for neighbours by neighbours. Info, support & guidance is available here and here. Manchester map of local mutual aid groups ● Mutual aid group organiser/admin? Share learning, ask & answer questions to other organisers. ● Public sector organisation looking for volunteers? Register needs with MCRVIP, or volunteer. ● 2,600 Manchester volunteers ready for your VCSE group or organisation - what do you need? Request or offer support. Support on managing volunteers, capacity-building & more. Social isolation and mental health ● The Resonance Centre is offering 12 free classes every week on Zoom, suitable for beginners and designed to help people with physical wellbeing and mental health - Yin and Vinyasa Yoga, Meditation, Pranayama, Art, plant-based cooking, and more.