Loves of Comfort and Despair: a Reading of Shakespeare's Sonnet 138 Author(S): Edward A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Booklet Shakespeare 3

SONNET 1 From fairest creatures we desire increase, That thereby beauty’s rose might never die, But as the riper should by time decease, His tender heir might bear his memory: But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes, Feed’st thy light’st flame with self-substantial fuel, Making a famine where abundance lies, Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel. Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament And only herald to the gaudy spring, Within thine own bud buriest thy content And, tender churl, makest waste in niggarding. Pity the world, or else this glutton be, To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee. SONNET 18 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm’d; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm’d; But thy eternal summer shall not fade Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest; Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou growest: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. SONNET 29 When, in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes, I all alone beweep my outcast state, And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries, And look upon myself, and curse my fate, Wishing me like to one more rich in hope, Featur'd like him, like him with friends possess'd, Desiring this man's art and that man's scope, With what I most enjoy contented least; Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising, Haply I think on thee, and then my state, Like to the lark at break of day arising From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven's gate; For thy sweet love remember'd such wealth brings That then I scorn to change my state with kings. -

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (SJHSS) ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) a Stylistic Approach of William Shakespeare's

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (SJHSS) ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) Scholars Middle East Publishers ISSN 2415-6248 (Online) Dubai, United Arab Emirates Website: http://scholarsmepub.com/ A Stylistic Approach of William Shakespeare’s “SONNET 138” Most Farhana Jannat* Lecturer, Department of English Bangladesh University of Professionals, Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka, Bangladesh Abstract: This paper aims to analyze the sonnet 138 written by William *Corresponding author Shakespeare from a stylistic point of view. The division of Shakespeare‟s sonnets Most Farhana Jannat is shown. A short introduction to both style and stylistics in literature are written. For further facilitation, a short introduction to Shakespeare, the sonnet 138 and its Article History themes are given. The stylistic analysis of the sonnet is shown from four sides. Received: 23.11.2017 Graphological, grammatical, phonological and lexical analyses are shown. This Accepted: 04.12.2017 paper will help to understand the structure and style of Shakespeare‟s sonnet Published: 30.12.2017 number 138. Moreover, the themes and ideals of Shakespeare will also be understood. DOI: Keywords: Sonnet, style, stylistic, graphological analysis, lexical analysis, 10.21276/sjhss.2017.2.12.1 grammatical analysis, phonological analysis, Shakespeare INTRODUCTION William Shakespeare is well known worldwide for his 154 sonnets. The critics believe that, among them, the first 1-126 is about the Fair Youth or the Earl of Southampton while the rest of the sonnets are written about the dark lady. Sonnet 138, among all the other sonnets in the sequence, is one of the most well- known sonnets. In this particular sonnet, the poet continues in his quest of self- criticism but mixes it with a unique love for the dark lady. -

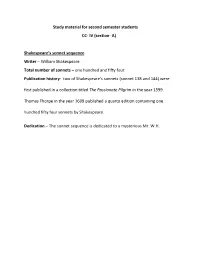

William Shakespeare. Total Number of Sonnets – One Hundred and Fifty Four

Study material for second semester students CC- IV (section- A) Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence Writer – William Shakespeare. Total number of sonnets – one hundred and fifty four. Publication history- two of Shakespeare’s sonnets (sonnet 138 and 144) were first published in a collection titled The Passionate Pilgrim in the year 1599. Thomas Thorpe in the year 1609 published a quarto edition containing one hundred fifty four sonnets by Shakespeare. Dedication – The sonnet sequence is dedicated to a mysterious Mr. W.H. Division: the first one hundred twenty six sonnets (1-126) are dedicated to an unnamed young man often mentioned as the ‘Fair Youth’. The last two sonnets (153 & 154) are addressed to Cupid and the rest of the sonnets (127-52) are dedicated to a mysterious woman or the Dark Lady. There is a fierce debate regarding the true identity of the ‘Fair Youth’ and the Dark Lady among Shakespeare scholars. Though some scholars propose that either William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke or Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton is most likely the mysterious young man and Mary Fitton is probably the Dark Lady of Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence, there is no irrefutable proof and therefore the debate is never resolved. Form – Barring a few exceptions, the sonnets of the sequence are written in Shakespearean sonnet style containing three quatrains and a final couplet. The sonnets generally are written in iambic pentameter. The sonnets follow the rhyme scheme abab cdcd efef gg. Exceptions- sonnet 99 has fifteen lines in stead of fourteen. Sonnet 126 has twelve lines written in the form of six couplets. -

Unit -3 Shakespeare : W.H. and Dark Lady 3.1 Objectives : 3.2

Unit -3 qqq Shakespeare : W.H. and Dark Lady Structure 3.1 Objectives 3.2 Shakespeare : Life and Works 3.3 Shakespeare’s Sonnets 3.4 The Text: W.H. 3.4.1 Sonnet I 3.4.2 Sonnet LV (55) 3.4.3 Sonnet CXVI (116) 3.4.4 Sonnet 126 3.5 The Text: Dark Lady 3.5.1 Sonnet CXXX (130) 3.5.2 Sonnet CXXXVIII (138) 3.6 Conclusion 3.7 Questions 3.8 Reference 3.1 qqq Objectives : I welcome you to this Unit but not without some hesitation. Some of you, 1 am afraid, may want to question the relevance as well as the utility of an introduction to William Shakespeare for, generally speaking, neither in your school nor in your college have you been too far away from the Bard of Avon. You could not have been. A student of English Literature cannot perhaps hope to graduate without reading Shakespeare because it will mean studying the human body and not learning about the heart and the circulatory system. Yet I feel that I should introduce or rather re-introduce Shakespeare to make you aware of certain facts/issues/controversies. 3.2 qqq Shakespeare : Life and Works From your study of Shakespeare at the undergraduate level, you know that a great deal 70 of mystery shrouds the poet-dramatist and his identity itself has been in question for many hundred years now. It has almost turned into a literary detective story, with enthusiasts trying to unveil the truth about a man known to have been born in Stratford-upon-Avon on 23 April 1564 and baptized on the 26th. -

SUGGESTED SONNETS 2015 / 2016 Season the English-Speaking Union National Shakespeare Competition INDEX of SUGGESTED SONNETS

SUGGESTED SONNETS 2015 / 2016 Season The English-Speaking Union National Shakespeare Competition INDEX OF SUGGESTED SONNETS Below is a list of suggested sonnets for recitation in the ESU National Shakespeare Competition. Sonnet First Line Pg. Sonnet First Line Pg. 2 When forty winters shall besiege thy brow 1 76 Why is my verse so barren of new pride 28 8 Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly? 2 78 So oft have I invok’d thee for my muse 29 10 For shame deny that thou bear’st love to any, 3 83 I never saw that you did painting need 30 12 When I do count the clock that tells the time 4 90 Then hate me when thou wilt, if ever, now, 31 14 Not from the stars do I my judgment pluck, 5 91 Some glory in their birth, some in their skill, 32 15 When I consider everything that grows 6 97 How like a winter hath my absence been 33 17 Who will believe my verse in time to come 7 102 My love is strengthened, though more weak… 34 18 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? 8 104 To me, fair friend, you never can be old, 35 20 A woman’s face with Nature’s own hand painted 9 113 Since I left you, mine eye is in my mind, 36 23 As an unperfect actor on the stage 10 116 Let me not to the marriage of true minds 37 27 Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed, 11 120 That you were once unkind befriends me now, 38 29 When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes 12 121 ’Tis better to be vile than vile esteemed, 39 30 When to the sessions of sweet silent thought 13 124 If my dear love were but the child of state, 40 34 Why didst thou promise such a beauteous day 14 126 O thou, my lovely boy, who in thy power 41 40 Take all my loves, my love, yea, take them all. -

Sonnets! Finale Event on Tuesday, October 20, 2020 at 6:30 P.M

SONNET TEXT FOR THINKING SHAKESPEARE LIVE: SONNETS! FINALE EVENT ON TUESDAY, OCTOBER 20, 2020 AT 6:30 P.M. PDT SONNET 18 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimmed; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimmed: But thy eternal summer shall not fade, Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st, Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. SONNET 138 When my love swears that she is made of truth, I do believe her, though I know she lies, That she might think me some untutored youth Unlearned in the world’s false subtleties. Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young, Although she knows my days are past the best, Simply I credit her false-speaking tongue; On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed. But wherefore says she not she is unjust? And wherefore say not I that I am old? O love’s best habit is in seeming trust, And age in love loves not t’have years told: Therefore I lie with her, and she with me, And in our faults by lies we flattered be. -

Sixteen Dramatically Illustrated Sonnets by Alan Haehnel Sonnet

Will and Whimsy: Sixteen Dramatically Illustrated Sonnets by Alan Haehnel Audition preparation: Listed are the sonnets we are performing, the synopsis of the scenes attached to that sonnet, and the demographic of the characters. Find 3-5 sonnets that speak to you and be prepared to read for those at auditions. Sonnet Scene Characters Gender Breakdown Sonnet 116 Josh is trying to propose to Laura Josh 1 male Let me not to the marriage of true minds Laura 1 female Admit impediments. Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove. O no! it is an ever-fixed mark That looks on tempests and is never shaken; It is the star to every wand'ring bark, Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken. Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks Within his bending sickle's compass come; Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, But bears it out even to the edge of doom. If this be error and upon me prov'd, I never writ, nor no man ever lov'd. Sonnet 89 Jake wants girlfriend Jessica to ‘fix’ him and all his Jake 1 male Say that thou didst forsake me for some fault, faults. Jessica 1 female And I will comment upon that offence: Speak of my lameness, and I straight will halt, Against thy reasons making no defence. Thou canst not, love, disgrace me half so ill, To set a form upon desired change, As I'll myself disgrace; knowing thy will, I will acquaintance strangle, and look strange; Be absent from thy walks; and in my tongue Thy sweet beloved name no more shall dwell, Lest I, too much profane, should do it wrong, And haply of our old acquaintance tell. -

Shakespeare's Sonnets

The McGill Department of English presents Infinithéâtre in collaboration with Early Modern Conversions Project in Shakespeare’s Sonnets: Transforming the Voices of Montréal Mo ys e Ha ll Mc G ill Un ive rs ity 853 S h e rb ro o ke S t W Mo n tre a l, Q C H3A 0G 5 Th e Mc G ill De p a rtm e n t o f En g lis h p re s e n ts In fin ith e a tre in c o lla b o ra tio n w ith E a rly Mo d e rn C o n ve rs io n s P ro je c t in : Mo n ,. O c t 22n d -S a t,. O c t 27th -8p m /2p m P roduction S pons or: S e a s on S pons or: Table of Contents 2...........................................................................................Table of Contents 3.................................................................................Infinithéâtre’s Mandate 4.... A few words on Shakespeare’s Sonnets: Transforming Voices of Montreal 5................An Introduction to Shakespearean Sonnets, a text by Lee Jamieson 7……………..................The Use Of Mask In The Workshop, a text by Brian Smith 9..…………..… More about Shakespeare’s Sonnets, a text by: Hannah Crawforth 13……………………………………….How to Analyze a Sonnet, a text by Lee Jamieson 16……........................................................................................A Few Sonnets 17……………………………………………………………………………..Questions and Exercises 18.................................................................................Sonnets Creative Team 19............................................................................................Thank you note 20.......................................................................References and What’s Next? Shakespeare’s Sonnets Study Guide | Infinithéâtre October 2018. 2 INFINITHÉÂTRE’S MANDATE REFLECTING AND EXPLORING LIFE IN 21st - CENTURY MONTRÉAL Infinithéâtre’s mission is to develop, produce and broker new Québec theatre to ever-widening audiences. -

The Concept of Love in Shakespeare's Sonnets

ISSN 1798-4769 Journal of Language Teaching and Research, Vol. 5, No. 4, pp. 918-923, July 2014 © 2014 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/jltr.5.4.918-923 The Concept of Love in Shakespeare’s Sonnets Fenghua Ma School of Foreign Languages, Jiangsu University, 212013 Zhenjiang, China Abstract—The present paper probes into the concept of love revealed in the Dark Lady group in Shakespeare’s Sonnets. In these poems, the poet depicts a kind of obsession, bitter, hopeless and degenerating, which is totally different from that sweet and ennobling love Shakespeare always pursues in his early works. It is argued that the conflict between the ideal of love and the sensual obsession with the Dark Lady may well be a manifestation of the change in the poet’s mood, namely, from optimism to pessimism. Index Terms—the concept of love, Dark Lady, Shakespeare’s Sonnets I. INTRODUCTION Since there are more legends than documented facts about Shakespeare‟s life, his life, in a sense, remains a mystery. Just for this reason, there were plenty of scholars who read Shakespeare‟s sonnets as his autobiography. In “Scorn Not the Sonnet”, for instance, Wordsworth wrote, “with this Key/ Shakespeare unlocked his heart…” (Gill, 2000, p.356). Although this argument is still open to discussion, many scholars seem to believe that sonnets, as lyrical poems, tend to convey more personal implications than other literary forms. Therefore, Shakespeare’s Sonnets bears a special meaning to his whole career of literary creation. These 154 sonnets, with their profound thought, luxuriant images, sincere and oceanic emotion, as well as artistic fascination, can by all means draw a parallel to his enduring plays. -

20 Questions: 15 Sonnets by Shakespeare

20 Questions: 15 Sonnets by Shakespeare 1. Sonnet 18: The rhyme scheme divides the poem into three quatrains and a couplet, but the statement of the poem divides differently. What word, in what line, signals the shift in the statement of the poem? 2. Sonnet 18: Paraphrase the poem in enough detail to show that you understand the literal meaning of every line. 3. Sonnet 27: Paraphrase the statement of each quatrain in enough detail to show that you understand the literal meaning of every line. 4. Sonnet 29: As in Sonnet 18 the rhyme scheme divides into three quatrains and a couplet but the statement of the poem divides rather differently. Describe this division. How is it similar to but different from the division of Sonnet 18? 5. Sonnet 29: Paraphrase the statement of each quatrain in enough detail to show that you understand the literal meaning of every line. 6. Sonnet 30 provides yet another variation in how the statement of the poem can be arranged. Describe the relationships among the three quatrains and compare the division of the statement here with Sonnets 18 and 29. 7. Sonnet 30: Paraphrase the statement of each quatrain in enough detail to show that you understand the literal meaning of every line. 8. Sonnet 60: Here each quatrain makes the same statement in a different way. Explain the imagery that Shakespeare uses in each quatrain to describe the inevitable changes brought by time. 9. Sonnet 64: Again each of the three quatrains make the same statement in a different way, and the statement is much the same as in Sonnet 60. -

Shakespeare's Sonnets

Name Period SHAKESPEARE’S SONNETS Who William Shakespeare is addressing in his 154 sonnets has been and continues to be debated. Some scholars even believe that the sonnets may not be a “true” sequence, meaning that they could have been written over many years and may be addressed to different men and women. Nevertheless, the widely accepted story is presented below. William Shakespeare (the poet and speaker in this sonnet sequence) begins with a set of 17 sonnets advising a beautiful, young man to marry and produce a child in the interest of preserving the family name and property, but even more in the interest of reproducing the young man’s remarkable beauty in his offspring. Sonnets 18-126 urge the poet’s love for the young man and claims that the young man’s beauty will be preserved in the very poems that we are now reading. These sonnets, which, in this supposed narrative, celebrate the poet’s love for the young man, include clusters of poems that seem to tell of such specific events as the young man’s mistreatment of the poet, the young man’s theft of the poet’s mistress, the appearance of “rival poets” who celebrate the young man and gain his favor, the poet’s separation from the young man through travel or through the young man’s indifference, and the poet’s infidelity to the young man. After those 109 poems, the sonnet sequence concludes with a third set (28 sonnets) to or about a woman who is presented as dark and treacherous and with whom the poet is sexually obsessed. -

A Lacanian Approach to Shakespeare's Sonnets

A LACANIAN APPROACH TO SHAKESPEARE’S SONNETS: LOVE, DESIRE AND PHANTASY Elif Derya Senduran* Abstract: Jouissance and desire are inseparable in Lacan’s terminology although some critics call jouissance as “the opposite pole of desire” (Braunstein 102). Jouissance is an ontological concept for Lacan. On the other hand, Lacan depicts desire as “lack of being”, “interpretation”, “desi- re is the desire of the Other”, “desire is the metonomy of being” (qtd. in Braunstein 102-103). Jouissance is not just pleasure or joy for Lacan although jouir means enjoy. Desire is the lack in being whereas jouissance is something expe- rienced by the body when pleasure is not pleasure anymore. Thus, Jouissance is beyond pleasure. Love, desire, phantasy, regarding jouissance are outstanding Lacanian aspects to analyse Shakespeare’s sonnets. Shakespeare’s a hundred and fifty-four sonnets signal variations in theme: sonnets from one to a hundred and twenty-six are written for a young man and the remaining sonnets are addressed to the Dark Lady. The sonnets, addressed to the young man praise an upper-class patron, yet obscene language evokes uncon- ventional associations of feelings which can be related to Lacan because according to Lacan people cannot show what they want in language and desire has a relationship with language (Sarup 13). In the case of the sonnets, the reader may obtain that it is the young man, the speaker favours, so the young man is reduced by the speaker to an object which is the Dark Lady because the speaker wants to possess the Leitura Flutuante, n. 4, pp.