A Lacanian Approach to Shakespeare's Sonnets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Booklet Shakespeare 3

SONNET 1 From fairest creatures we desire increase, That thereby beauty’s rose might never die, But as the riper should by time decease, His tender heir might bear his memory: But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes, Feed’st thy light’st flame with self-substantial fuel, Making a famine where abundance lies, Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel. Thou that art now the world’s fresh ornament And only herald to the gaudy spring, Within thine own bud buriest thy content And, tender churl, makest waste in niggarding. Pity the world, or else this glutton be, To eat the world’s due, by the grave and thee. SONNET 18 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm’d; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance or nature’s changing course untrimm’d; But thy eternal summer shall not fade Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest; Nor shall Death brag thou wander’st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou growest: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. SONNET 29 When, in disgrace with fortune and men's eyes, I all alone beweep my outcast state, And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries, And look upon myself, and curse my fate, Wishing me like to one more rich in hope, Featur'd like him, like him with friends possess'd, Desiring this man's art and that man's scope, With what I most enjoy contented least; Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising, Haply I think on thee, and then my state, Like to the lark at break of day arising From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven's gate; For thy sweet love remember'd such wealth brings That then I scorn to change my state with kings. -

The Subversive Nature of the Dark Lady Sonnets: a Reading of Sonnets 129 and 144

Annali di Ca’ Foscari. Serie occidentale [online] ISSN 2499-1562 Vol. 49 – Settembre 2015 [print] ISSN 2499-2232 «My Female Evil» The Subversive Nature of the Dark Lady Sonnets: a Reading of Sonnets 129 and 144 Camilla Caporicci (Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München, Deutschland) Abstract Shakespeare’s opposition towards some aspects of Stoic and Neoplatonic doctrines and religious fanaticism, particularly Puritanism, can be found in many of his plays. However, rather than focusing on the dramatic output, this essay will concentrate on Shakespeare’s Sonnets. The strongly subversive nature of the Dark Lady section is especially notable, although modern critical opinion is generally less inclined to acknowledge its subversive philosophical message because of the supposedly more ‘personal’ nature of lyrical expression compared to the dramatic. In fact, critics have generally chosen to focus their attention on the Fair Youth section, more or less intentionally ignoring the Sonnets’ second part, summarily dismissed as an example of parodic inversion of the Petrarchan model, thus avoiding an examination of its profound revolutionary character, that is – an implicit rejection of the Christian and Neo-platonic basis of the sonnet tradi- tion. Through a close reading of two highly meaningful sonnets, this essay will show that, in the poems dedicated to the Dark Lady, Shakespeare calls into question, through clear terminological reference, the very foundations of Christian and Neo-platonic thought – such as the dichotomous nature of creation, the supremacy of the soul over the body, the conception of sin et cetera – in order to show their internal inconsistencies, and to propose instead a new ontological paradigm, based on materialistic and Epicurean principles, that proclaims reality to consist of an indissoluble union of spirit and matter. -

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (SJHSS) ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) a Stylistic Approach of William Shakespeare's

Saudi Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences (SJHSS) ISSN 2415-6256 (Print) Scholars Middle East Publishers ISSN 2415-6248 (Online) Dubai, United Arab Emirates Website: http://scholarsmepub.com/ A Stylistic Approach of William Shakespeare’s “SONNET 138” Most Farhana Jannat* Lecturer, Department of English Bangladesh University of Professionals, Mirpur Cantonment, Dhaka, Bangladesh Abstract: This paper aims to analyze the sonnet 138 written by William *Corresponding author Shakespeare from a stylistic point of view. The division of Shakespeare‟s sonnets Most Farhana Jannat is shown. A short introduction to both style and stylistics in literature are written. For further facilitation, a short introduction to Shakespeare, the sonnet 138 and its Article History themes are given. The stylistic analysis of the sonnet is shown from four sides. Received: 23.11.2017 Graphological, grammatical, phonological and lexical analyses are shown. This Accepted: 04.12.2017 paper will help to understand the structure and style of Shakespeare‟s sonnet Published: 30.12.2017 number 138. Moreover, the themes and ideals of Shakespeare will also be understood. DOI: Keywords: Sonnet, style, stylistic, graphological analysis, lexical analysis, 10.21276/sjhss.2017.2.12.1 grammatical analysis, phonological analysis, Shakespeare INTRODUCTION William Shakespeare is well known worldwide for his 154 sonnets. The critics believe that, among them, the first 1-126 is about the Fair Youth or the Earl of Southampton while the rest of the sonnets are written about the dark lady. Sonnet 138, among all the other sonnets in the sequence, is one of the most well- known sonnets. In this particular sonnet, the poet continues in his quest of self- criticism but mixes it with a unique love for the dark lady. -

Shakespeare, the Fair Young Man and the Dark Lady

Högskolan Dalarna English C Literature Essay Supervisors: Elizabeth Kella, Irene Gilsenan-Nordin Breaking the Conventions: Shakespeare, the Fair Young Man and the Dark Lady VS Autumn 2005 30th March 2006 Artyom Kulagin Box 166 SE-177 23 JÄRFÄLLA E-Mail: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………….....2 2. Petrarch Versus Shakespeare: Blonde Versus Brunette………………………..6 3. The Dark Lady: an Alluring but Degraded Object of Desire…..…..…………..9 4. Shakespeare and the Fair Young Man………………………………………...11 5. The Love Triangle in Shakespeare’s Sonnets…………………………………15 6. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………….18 7. Works Cited……………………………………………………………...……20 8. Appendix…………………………………………………………………....…21 2 Introduction What we need most, is not so much to realise the ideal as to idealise the real. Francis Herbert Hedge According to Meyer H. Abrams, in the competitive and vital world of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, the overcoming of the human spirit unleashed curiosity, individual self-assertion, and a powerful conviction that man was the measure of all things (472). In the Renaissance, the literary images of the human being appeared to be perfect and unattainable, aiming to improve society through the perfection of the individual. It was achieved by means of literature and its different forms. The most explicit form for conveying the beauty and perfection of a human being to be used was the poem. Love verses, odes devoted to queens and lyrical songs of various kinds were the best weapon in the love arsenal of poets. Regardless of a vast variety of different poetic forms, however, poets in their verses encompassed all possible themes and, therefore, were searching for something new, more expressive, unique and revolutionary to some extent. -

Deception and Self-Deception in the Dark Lady Sonnets

ISSN 2249-4529 Lapis Lazuli An International Literary Journal WWW.PINTERSOCIETY.COM VOL.6 / NO.1-2/SPRING, AUTUMN 2016 Deception and Self-Deception in the Dark Lady Sonnets Abhinaba Chatterjee Abstract: Shakespeare's sonnets, especially those addressed to the 'Dark Lady', reveal the dilemmas of a male character, trapped in the conventions of the time and his own inner instincts of sexual gratification. This paper analyses this aspect of the poet-narrator, both from the empowered position of the dark lady and as the conflict between the eternal opposites of the psyche, the conflict of the ego and the id, the Elizabethan convention of treating women as an equal and the male desire for sexual gratification. Keywords: Shakespeare, Sonnet-sequence, dark lady, Elizabethan convention, female subjectivity, distortion, abjection, sexuality, Christianity, Neoplatonism The sonnets 127-152 are addressed to an older woman who provokes love and revulsion simultaneously in the poet. Shakespeare’s poetry dramatizes the power of stigmatizing discourse of promiscuity to distort female subjectivity, revealing in the process the contradictions of the logic on which this distortion rests. It is the evacuation of subjectivity that the dark lady refuses when she presumes to occupy the male province of carnal desire. However, contrary to critical consensus, it is not her promiscuity as such that so disturbs the speaker of the Sonnets. Rather, it is her assertion of 42 VOL.6 / NO.1-2/ SPRING, AUTUMN 2016 sexual subjectivity; of agency and choice, which threatens the male prerogative he claims – the dark lady wants some men (may be many men) but she does not want all of them. -

William Shakespeare. Total Number of Sonnets – One Hundred and Fifty Four

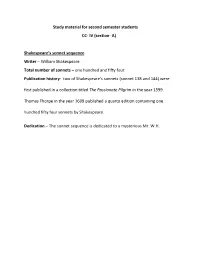

Study material for second semester students CC- IV (section- A) Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence Writer – William Shakespeare. Total number of sonnets – one hundred and fifty four. Publication history- two of Shakespeare’s sonnets (sonnet 138 and 144) were first published in a collection titled The Passionate Pilgrim in the year 1599. Thomas Thorpe in the year 1609 published a quarto edition containing one hundred fifty four sonnets by Shakespeare. Dedication – The sonnet sequence is dedicated to a mysterious Mr. W.H. Division: the first one hundred twenty six sonnets (1-126) are dedicated to an unnamed young man often mentioned as the ‘Fair Youth’. The last two sonnets (153 & 154) are addressed to Cupid and the rest of the sonnets (127-52) are dedicated to a mysterious woman or the Dark Lady. There is a fierce debate regarding the true identity of the ‘Fair Youth’ and the Dark Lady among Shakespeare scholars. Though some scholars propose that either William Herbert, 3rd Earl of Pembroke or Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton is most likely the mysterious young man and Mary Fitton is probably the Dark Lady of Shakespeare’s sonnet sequence, there is no irrefutable proof and therefore the debate is never resolved. Form – Barring a few exceptions, the sonnets of the sequence are written in Shakespearean sonnet style containing three quatrains and a final couplet. The sonnets generally are written in iambic pentameter. The sonnets follow the rhyme scheme abab cdcd efef gg. Exceptions- sonnet 99 has fifteen lines in stead of fourteen. Sonnet 126 has twelve lines written in the form of six couplets. -

Unit -3 Shakespeare : W.H. and Dark Lady 3.1 Objectives : 3.2

Unit -3 qqq Shakespeare : W.H. and Dark Lady Structure 3.1 Objectives 3.2 Shakespeare : Life and Works 3.3 Shakespeare’s Sonnets 3.4 The Text: W.H. 3.4.1 Sonnet I 3.4.2 Sonnet LV (55) 3.4.3 Sonnet CXVI (116) 3.4.4 Sonnet 126 3.5 The Text: Dark Lady 3.5.1 Sonnet CXXX (130) 3.5.2 Sonnet CXXXVIII (138) 3.6 Conclusion 3.7 Questions 3.8 Reference 3.1 qqq Objectives : I welcome you to this Unit but not without some hesitation. Some of you, 1 am afraid, may want to question the relevance as well as the utility of an introduction to William Shakespeare for, generally speaking, neither in your school nor in your college have you been too far away from the Bard of Avon. You could not have been. A student of English Literature cannot perhaps hope to graduate without reading Shakespeare because it will mean studying the human body and not learning about the heart and the circulatory system. Yet I feel that I should introduce or rather re-introduce Shakespeare to make you aware of certain facts/issues/controversies. 3.2 qqq Shakespeare : Life and Works From your study of Shakespeare at the undergraduate level, you know that a great deal 70 of mystery shrouds the poet-dramatist and his identity itself has been in question for many hundred years now. It has almost turned into a literary detective story, with enthusiasts trying to unveil the truth about a man known to have been born in Stratford-upon-Avon on 23 April 1564 and baptized on the 26th. -

SUGGESTED SONNETS 2015 / 2016 Season the English-Speaking Union National Shakespeare Competition INDEX of SUGGESTED SONNETS

SUGGESTED SONNETS 2015 / 2016 Season The English-Speaking Union National Shakespeare Competition INDEX OF SUGGESTED SONNETS Below is a list of suggested sonnets for recitation in the ESU National Shakespeare Competition. Sonnet First Line Pg. Sonnet First Line Pg. 2 When forty winters shall besiege thy brow 1 76 Why is my verse so barren of new pride 28 8 Music to hear, why hear’st thou music sadly? 2 78 So oft have I invok’d thee for my muse 29 10 For shame deny that thou bear’st love to any, 3 83 I never saw that you did painting need 30 12 When I do count the clock that tells the time 4 90 Then hate me when thou wilt, if ever, now, 31 14 Not from the stars do I my judgment pluck, 5 91 Some glory in their birth, some in their skill, 32 15 When I consider everything that grows 6 97 How like a winter hath my absence been 33 17 Who will believe my verse in time to come 7 102 My love is strengthened, though more weak… 34 18 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? 8 104 To me, fair friend, you never can be old, 35 20 A woman’s face with Nature’s own hand painted 9 113 Since I left you, mine eye is in my mind, 36 23 As an unperfect actor on the stage 10 116 Let me not to the marriage of true minds 37 27 Weary with toil, I haste me to my bed, 11 120 That you were once unkind befriends me now, 38 29 When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes 12 121 ’Tis better to be vile than vile esteemed, 39 30 When to the sessions of sweet silent thought 13 124 If my dear love were but the child of state, 40 34 Why didst thou promise such a beauteous day 14 126 O thou, my lovely boy, who in thy power 41 40 Take all my loves, my love, yea, take them all. -

Sonnets! Finale Event on Tuesday, October 20, 2020 at 6:30 P.M

SONNET TEXT FOR THINKING SHAKESPEARE LIVE: SONNETS! FINALE EVENT ON TUESDAY, OCTOBER 20, 2020 AT 6:30 P.M. PDT SONNET 18 Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer’s lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimmed; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance, or nature’s changing course, untrimmed: But thy eternal summer shall not fade, Nor lose possession of that fair thou ow’st, Nor shall death brag thou wander’st in his shade When in eternal lines to time thou grow’st: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this, and this gives life to thee. SONNET 138 When my love swears that she is made of truth, I do believe her, though I know she lies, That she might think me some untutored youth Unlearned in the world’s false subtleties. Thus vainly thinking that she thinks me young, Although she knows my days are past the best, Simply I credit her false-speaking tongue; On both sides thus is simple truth suppressed. But wherefore says she not she is unjust? And wherefore say not I that I am old? O love’s best habit is in seeming trust, And age in love loves not t’have years told: Therefore I lie with her, and she with me, And in our faults by lies we flattered be. -

Sixteen Dramatically Illustrated Sonnets by Alan Haehnel Sonnet

Will and Whimsy: Sixteen Dramatically Illustrated Sonnets by Alan Haehnel Audition preparation: Listed are the sonnets we are performing, the synopsis of the scenes attached to that sonnet, and the demographic of the characters. Find 3-5 sonnets that speak to you and be prepared to read for those at auditions. Sonnet Scene Characters Gender Breakdown Sonnet 116 Josh is trying to propose to Laura Josh 1 male Let me not to the marriage of true minds Laura 1 female Admit impediments. Love is not love Which alters when it alteration finds, Or bends with the remover to remove. O no! it is an ever-fixed mark That looks on tempests and is never shaken; It is the star to every wand'ring bark, Whose worth's unknown, although his height be taken. Love's not Time's fool, though rosy lips and cheeks Within his bending sickle's compass come; Love alters not with his brief hours and weeks, But bears it out even to the edge of doom. If this be error and upon me prov'd, I never writ, nor no man ever lov'd. Sonnet 89 Jake wants girlfriend Jessica to ‘fix’ him and all his Jake 1 male Say that thou didst forsake me for some fault, faults. Jessica 1 female And I will comment upon that offence: Speak of my lameness, and I straight will halt, Against thy reasons making no defence. Thou canst not, love, disgrace me half so ill, To set a form upon desired change, As I'll myself disgrace; knowing thy will, I will acquaintance strangle, and look strange; Be absent from thy walks; and in my tongue Thy sweet beloved name no more shall dwell, Lest I, too much profane, should do it wrong, And haply of our old acquaintance tell. -

Sonnet 144 by William Shakespeare Two Loves I Have, of Comfort And

B.A. II (Opt. Eng.), Semester III Study of Poetry: Sonnets & Elegy—V Sonnet 144 by William Shakespeare Two loves I have, of comfort and despair, Which like two spirits, do suggest me still; The better angel is a man right fair, The worser spirit a woman colored ill. To win me soon to hell, ma female evil Tempteth my vetter angel from my side, And would corrupt my saint to be a devil, Wooing his purity with her foul pride. And whether that my angel be turned fiend Suspect I may, but not directly tell; But being both form me, both to each friend, I guess one angel in another’s hell. Yet this shall I ne’er know, but live in doubt, Till my bad angel fire my good one out. Summary: Sonnet 144 is the only sonnet that explicitly refers to both the Dark Lady and the young man, the poet's "Two loves." Atypically, the poet removes himself from the love triangle and tries to consider the situation with detachment. The humor of the previous sonnet is missing, and the poet's mood is cynical and mocking, in part because uncertainty about the relationship torments him. Although the sonnet is unique in presenting the poet's attempt to be objective about the two other figures in the relationship, stylistically it is very similar to others in terms of setting up an antithesis between two warring elements, the youth ("comfort") and the woman ("despair"): "The better angel is a man right fair, / The worser spirit a woman, colored ill." Symbolically, the young man and the woman represent two kinds of love battling for supremacy within the poet's own character: selfless adoration and shameful lust, respectively. -

Woman's Reflection in Shakespeare's Sonnets

WOMAN’S REFLECTION IN SHAKESPEARE’S SONNETS Ramona CHIRIBUŢĂ∗ Abstract: Shakespeare’s paired portraits of a beautiful, unattainable young man and a dark, promiscuous woman can easily be read as expressions of the deepest misogyny. But it is worth remembering that the Petrarchan tradition he challenged was also consistent with misogyny. Petrarch himself had written misogynist satires on women, and the objectified, ideal lady of the Petrarchan sonnet tradition stood as an implicit rebuke to the human imperfection of women as they actually were. The Petrarchan lady modelled the features that constituted a beautiful woman – in life as well as in art. Petrarch’s figuration of Laura’ played a crucial role in the development of a code of beauty... that causes us to view the fetish zed body as a norm and encourages us to seek, or to seek to be, ideal types, beautiful monsters composed of every individual perfection. Keywords: misogyny, effeminate men, protofeminist, lust, fetishism. Like “Romeo and Juliet”, Shakespeare’s sonnets stage a complicated negotiation with the Petrarchan tradition. Written at a time when the vogue of the sonnet sequence was so familiar that it was an easy subject to parody, even in plays written for the amusement of a public theatre audience, Shakespeare’s sonnets were clearly belated. They were also novel, however, in two important respects. In the first place, their repeated subject is the speaker’s devotion to a beautiful young man. Other poets, as far back as Dante and Petrarch, had written occasional sonnets of praise to male patrons and friends, but in Shakespeare’s, the figure of the beautiful young man is assigned the central role traditionally occupied by the Petrarchan lady.