Deuteronomy in the Temple Scroll and Its Use in the Textual Criticism of Deuteronomy*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditions About Miriam in the Qumran Scrolls

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department Classics and Religious Studies 2003 Traditions about Miriam in the Qumran Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub Part of the Classics Commons Crawford, Sidnie White, "Traditions about Miriam in the Qumran Scrolls" (2003). Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department. 97. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/97 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in STUDIES IN JEWISH CIVILIZATION, VOLUME 14: WOMEN AND JUDAISM, ed. Leonard J. Greenspoon, Ronald A. Simkins, & Jean Axelrad Cahan (Omaha: Creighton University Press, 2003), pp. 33-44. Traditions about Miriam in the Qumran Scrolls Sidnie White Crawford The literature of Second Temple Judaism (late sixth century BCE to 70 CE) contains many compositions that focus on characters and events known from the biblical texts. The characters or events in these new compositions are developed in various ways: filling in gaps in the biblical account, offering explanations for difficult passages, or simply adding details to the lives of biblical personages to make them fuller and more interesting characters. For example, the work known as Joseph andAseneth focuses on the biblical character Aseneth, the Egyptian wife of Joseph, mentioned only briefly in Gen 41:45, 50.' This work attempts to explain, among other things, how Joseph, the righteous son of Jacob, contracted an exogamous marriage with the daughter of an Egyptian priest. -

BSBB9401 DEAD SEA SCROLLS Fall 2018 Dr. R. Dennis Cole NOBTS Mcfarland Chair of Archaeology Dodd Faculty 201 [email protected] 504-282-4455 X3248

BSBB9401 DEAD SEA SCROLLS Fall 2018 Dr. R. Dennis Cole NOBTS Mcfarland Chair of Archaeology Dodd Faculty 201 [email protected] 504-282-4455 x3248 NOBTS MISSION STATEMENT The mission of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary is to equip leaders to fulfill the Great Commission and the Great Commandments through the local church and its ministries. COURSE PURPOSE, CORE VALUE FOCUS, AND CURRICULUM COMPETENCIES New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary has five core values: Doctrinal Integrity, Spiritual Vitality, Mission Focus, Characteristic Excellence, and Servant Leadership. These values shape both the context and manner in which all curricula are taught, with “doctrinal integrity” and “characteristic academic excellence” being especially highlighted in this course. NOBTS has seven basic competencies guiding our degree programs. The student will develop skills in Biblical Exposition, Christian Theological Heritage, Disciple Making, Interpersonal Skills, Servant Leadership, Spiritual & Character Formation, and Worship Leadership. This course addresses primarily the compentency of “Biblical Exposition” competency by helping the student learn to interpret the Bible accurately through a better understanding of its historical and theological context. During the Academic Year 2018-19, the focal competency will be Doctrinal Integrity.. COURSE DESCRIPTION Research includes historical background and description of the Qumran cult and problems relating to the significance and dating of the Scrolls. Special emphasis is placed on a theological analysis of the non- biblical texts of the Dead Sea library on subjects such as God, man, and eschatology. Meaningful comparisons are sought in the Qumran view of sin, atonement, forgiveness, ethics, and messianic expectation with Jewish and Christian views of the Old and New Testaments as well as other Interbiblical literature. -

![Qumran Hebrew (With a Trial Cut [1Qs])*](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9626/qumran-hebrew-with-a-trial-cut-1qs-1289626.webp)

Qumran Hebrew (With a Trial Cut [1Qs])*

QUMRAN HEBREW (WITH A TRIAL CUT [1QS])* Gary A. Rendsburg Rutgers University One would think that after sixty years of studying the scrolls, scholars would have reached a consensus concerning the nature of the language of these texts. But such is not the case—the picture is no different for Qumran Hebrew (QH) than it is for identifying the sect of the Qum- ran community, for understanding the origins of the scroll depository in the caves, or for the classification of the archaeological remains at Qumran. At first glance, this is a bit difficult to comprehend, since in theory, at least, linguistic research should be the most objective form of scholarly inquiry, and the facts should speak for themselves—in contrast to, let’s say, the interpretation of texts, where subjectivity may be considered necessary at all times. But as we shall see, even though the data themselves are derived from purely empirical observation, the interpretation of the linguistic picture that emerges from the study of Qumran Hebrew has no less a range of options than the other subjects canvassed during this symposium. Before entering into such discussion, however, let us begin with the presentation of some basic facts. Of the 930 assorted documents from Qumran, 790, or about 85% of them are written in Hebrew (120 or about 13% are written in Aramaic, and 20 or about 2% are written in Greek). Of these 930, about 230 are biblical manuscripts, which * It was my pleasure to present this paper on three occasions during calendar year 2008: first and most importantly at the symposium entitled “The Dead Sea Scrolls at 60: The Scholarly Contributions of NYU Faculty and Alumni” (March 6), next at the “Semitic Philology Workshop” of Harvard University (November 20), and finally at the panel on “New Directions in Dead Sea Scrolls Scholarship” at the annual meeting of the Association of Jewish Studies held in Washington, D.C. -

The Meaning of the Phrase ציר המקרש in the Temple Scroll

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department Classics and Religious Studies September 2001 IN THE TEMPLE ציר המקרש THE MEANING OF THE PHRASE SCROLL* Sidnie White Crawford University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub Part of the Classics Commons .(IN THE TEMPLE SCROLL*" (2001 ציר המקרש Crawford, Sidnie White, "THE MEANING OF THE PHRASE Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department. 6. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/classicsfacpub/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Classics and Religious Studies at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Classics and Religious Studies Department by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. THE MEANING OF THE PHRASE IN THE TEMPLE SCROLL * SIDNIE WHITE CRAWFORD University of Nebraska-Lincoln A minor point of contention in the interpretation of the Temple Scroll has been the meaning of the phrase found in the laws concerning the purity of the ideal sanctuary envisioned by the Temple Scroll. This phrase is not a biblical phrase; therefore we can- not fall back on a biblical meaning to help us determine its meaning. The problem is compounded by the fact that the Temple Scroll uses a variety of terms to refer to the Temple building itself, the various buildings and courts which surround it, and the wider area around it; these terms overlap and a clear distinction in terminology is not dis- cernible. These terms include , , , , , , , and the phrase presently under consideration, (see Appendix 1). -

A Study on the Teacher of Righteousness, Collective Memory, and Tradition at Qumran by Gianc

MANUFACTURING HISTORY AND IDENTITY: A STUDY ON THE TEACHER OF RIGHTEOUSNESS, COLLECTIVE MEMORY, AND TRADITION AT QUMRAN BY GIANCARLO P. ANGULO A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Religion May 2014 Winston Salem, North Carolina Approved By: Kenneth G. Hoglund, Ph.D., Advisor Jarrod Whitaker, Ph.D., Chair Clinton J. Moyer, Ph.D. Acknowledgments It would not be possible to adequately present the breadth of my gratitude in the scope of this short acknowledgment section. That being said, I would like to extend a few thanks to some of those who have most influenced my academic and personal progression during my time in academia. To begin, I would be remiss not to mention the many excellent professors and specifically Dr. Erik Larson at Florida International University. The Religious Studies department at my undergraduate university nurtured my nascent fascination with religion and the Dead Sea Scrolls and launched me into the career I am now seeking to pursue. Furthermore, a thank you goes out to my readers Dr. Jarrod Whitaker and Dr. Clinton Moyer. You have both presented me with wonderful opportunities during my time at Wake Forest University that have helped to develop me into the student and speaker I am today. Your guidance and review of this thesis have proven essential for me to produce my very best work. Also, a very special thank you must go out to my advisor, professor, and friend, Dr. Ken Hoglund. -

Chaos Theory and the Text of the Old Testament1 Peter J

Chaos Theory and the Text of the Old Testament1 Peter J. Gentry Peter J. Gentry is Donald L. Williams Professor of Old Testament Interpretation and Director of the Hexapla Institute at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He has served on the faculty of Toronto Baptist Seminary and Bible College and also taught at the University of Toronto, Heritage Theological Seminary, and Tyndale Seminary. Dr. Gentry is the author of many articles and book reviews, the co-author of Kingdom through Covenant, 2nd ed. (Crossway, 2018) and God’s Kingdom through God’s Covenants (Crossway, 2015), and the author of How to Read and Understand the Biblical Prophets (Crossway, 2017), and he recently published a critical edition of Ecclesiastes for the Göttingen Septuagint (2019). Introduction Canon and Text are closely related. For those who believe in divine revelation mediated by authorized agents, the central questions are (1) which writings come from these agents authorized to speak for God and (2) have their writings been reliably transmitted to us? Although my inquiry is focused on the latter question, the former is logically prior. How one answers the first question will determine evaluation of evidence relating to the second. What defines a canonical text according to Nahum Sarna, is “a fixed arrangement of content” and “the tendency to produce a standardized text.”2 Since the very first biblical text constituted a covenant, this automatically implies a fixed arrangement of content and a standard text. I am referring to the Covenant at Sinai, a marriage between Yahweh and Israel. A marriage contract does not have a long oral pre-history. -

The New Testament Κύριος Problem and How the Old Testament Speeches Can Help Solve It

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 14 Original Research The New Testament κύριος problem and how the Old Testament speeches can help solve it Author: The New Testament (NT) κύριος problem forms part of a larger interconnected network of 1 Peter Nagel challenges, which has the divine name Yhwh as the epicentre. To put it plainly, if the term Affiliation: κύριος is an equivalent for the divine name Yhwh and if the term κύριος in the Yhwh sense is 1Department of Old and New applied to Jesus, the implication is that Jesus is put on par with Yhwh. This problem therefore, Testament, Faculty of forms part of a matrix of interconnected issues in a constant push and pull relation. There is no Theology, Stellenbosch easy way to address this problem, but one must start somewhere. This study will attempt to University, Stellenbosch, South Africa introduce, illustrate and explain the complexity of the NT κύριος problem to contribute to a deeper understanding of the problem and to appreciate its intricacies. The aim is therefore to Corresponding author: illustrate the intricacy of the problem by showing where the NT κύριος problem might have Peter Nagel, originated and how it evolved. These intricacies will then be pulled into a singular focus made [email protected] possible by the explicit κύριος citations. These citations, in turn, will be categorised as Theos, Dates: Davidic and Jesus speeches and analysed in an attempt to contribute to a possible solution. Received: 18 May 2020 Accepted: 16 June 2020 Contribution: This article fits in well with the contestation of ‘historical thought’ and ‘source Published: 30 Oct. -

The Valediction of Moses

Forschungen zum Alten Testament Edited by Konrad Schmid (Zürich) · Mark S. Smith (Princeton) Hermann Spieckermann (Göttingen) · Andrew Teeter (Harvard) 145 Idan Dershowitz The Valediction of Moses A Proto-Biblical Book Mohr Siebeck Idan Dershowitz: born 1982; undergraduate and graduate training at the Hebrew University, following several years of yeshiva study; 2017 elected to the Harvard Society of Fellows; currently Chair of Hebrew Bible and Its Exegesis at the University of Potsdam. orcid.org/0000-0002-5310-8504 Open access sponsored by the Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law at the Harvard Law School. ISBN 978-3-16-160644-1 / eISBN 978-3-16-160645-8 DOI 10.1628/978-3-16-160645-8 ISSN 0940-4155 / eISSN 2568-8359 (Forschungen zum Alten Testament) The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliographie; detailed bibliographic data are available at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Mohr Siebeck Tübingen, Germany. www.mohrsiebeck.com This work is licensed under the license “Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 Inter- national” (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). A complete Version of the license text can be found at: https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Any use not covered by the above license is prohibited and illegal without the permission of the publisher. The book was printed on non-aging paper by Gulde Druck in Tübingen, and bound by Buch- binderei Spinner in Ottersweier. Printed in Germany. Acknowledgments This work would not have been possible without the generosity of my friends, family, and colleagues. The Harvard Society of Fellows provided the ideal environment for this ven- ture.Atatimeinwhichacademiaisbecomingincreasinglyriskaverse,theSociety remains devoted to supporting its fellows’ passion projects. -

11Q19 Temple Scroll

11Q19 Temple Scroll Donald W. Parry 11Q19 Temple Scroll was found in Cave 11 in 1956. At twenty-eight feet, it is the longest scroll among the Qumran nds. Much of this scroll’s sixty-six columns examines various physical aspects of the temple at Jerusalem that would be built in a future day—its construction and measurements, the Holy of Holies, the chambers and colonnades, the mercy seat, cherubim, veil, table, golden lampstand, altar, and courtyards. The Temple Scroll also describes the ideal temple society with a discussion of a covenant between God and Israel, purity regulations, judges and ofcers, vows and oaths, detailed statutes of the Jewish king, crimes punishable by hanging, and laws relating to idolatry, sacricial animals, apostasy, priests, Levites, priestly dues, witnesses, the conduct of war, and rebellious sons. The scroll does not simply repeat the laws on temple worship and social conduct as they appear in the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy, but blends them into a new, harmonious whole, sometimes adding new materials, such as festivals of new oil and wine that are not mentioned in the law of Moses. In short, the temple, according to the scroll itself, is “the temple on which I [the Lord] will settle my glory until the day of blessing on which I will create my temple and establish it for myself for all times” (29:7– 10). Many third-person statements in the books of Moses are given in rst person in the Temple Scroll. Because this shift eliminates Moses as an intermediary, the scroll is presented as a revelation given directly from God to Israel.1 Thus the Temple Scroll “purports to be the community’s Second Torah,”2 and as such it is an important additional source on theology in the Second Temple period. -

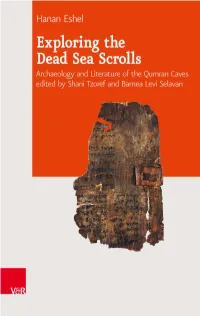

Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls

Hanan Eshel, Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls © 2015, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525550960 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647550961 Hanan Eshel, Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls Journal of Ancient Judaism Supplements Edited by Armin Lange, Bernard M. Levinson and Vered Noam Advisory Board Katell Berthelot (University of Aix-Marseille), George Brooke (University of Manchester), Jonathan Ben Dov (University of Haifa), Beate Ego (University of Osnabrück), Esther Eshel (Bar-Ilan University), Heinz-Josef Fabry (University of Bonn), Steven Fraade (Yale University), Maxine L. Grossman (University of Maryland), Christine Hayes (Yale University), Catherine Hezser (University of London), Alex Jassen (University of Minnesota), James L. Kugel (Bar-Ilan University), Jodi Magness (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill), Carol Meyers, (Duke University), Eric Meyers (Duke University), Hillel Newman (University of Haifa), Christophe Nihan (University of Lausanne), Lawrence H. Schiffman (New York University), Konrad Schmid (University of Zurich), Adiel Schremer (Bar-Ilan University), Michael Segal (Hebrew University of Jerusalem), Aharon Shemesh (Bar-Ilan University), Günter Stemberger (University of Vienna), Kristin De Troyer (University of St. Andrews), Azzan Yadin (Rutgers University) Volume 18 Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht © 2015, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525550960 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647550961 Hanan Eshel, Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls Hanan Eshel Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls Archaeology and Literature of the Qumran Caves edited by Shani Tzoref / Barnea Levi Selavan Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht © 2015, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht GmbH & Co. KG, Göttingen ISBN Print: 9783525550960 — ISBN E-Book: 9783647550961 Hanan Eshel, Exploring the Dead Sea Scrolls This volume is generously sponsored by the David and Jemima Jeselsohn Epigraphic Center for Jewish History. -

The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls

Archaeology and Biblical Studies Andrew G. Vaughn, Editor Number 14 The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls by C. D. Elledge Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta The Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls Copyright © 2005 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Offi ce, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Elledge, C. D. (Casey Deryl) Th e Bible and the Dead Sea Scrolls / by C. D. Elledge. p. cm. — (Archaeology and biblical studies; 14) Includes indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-58983-183-4 (paper binding : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-58983-183-7 (paper binding : alk. paper) 1. Dead Sea scrolls. 2. Bible—Criticism, interpretation, etc. I. Title. II. Series. BM487.E45 2005 296.1'55—dc22 2005016939 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence. CONTENTS Preface vii Abbreviations x . What Are the Dead Sea Scrolls and How Were They Discovered? ................................................................1 The Unlikely Discovery of an Ancient Library 1 Controversies Solved through International Cooperation 8 Major Publications of the Dead Sea Scrolls 11 . -

HOW to REWRITE TORAH: the Case for Proto-Sectarian Ideology in the Reworked Pentateuch (4QRP)*

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary Portland Seminary 2007 How to Rewrite Torah: The aC se for Proto- Sectarian Ideology in the Reworked Pentateuch (4QRP) Roger S. Nam George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Nam, Roger S., "How to Rewrite Torah: The asC e for Proto-Sectarian Ideology in the Reworked Pentateuch (4QRP)" (2007). Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary. 87. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/gfes/87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Portland Seminary at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Portland Seminary by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOW TO REWRITE TORAH: The Case for Proto-Sectarian Ideology in the Reworked Pentateuch (4QRP)* Summary This study challenges the initial categorization of the Reworked Penta teuch (4Q364-4Q367) as another non-sectarian textual witness to the Torah. A close analysis of the manuscripts suggests that certain unaligned readings likely ret1ect some of the sectarian ideas of the community. Other variants evoke both content and ideology of the authoritative "Rewritten Bible" documents, the Temple Scroll and Jubilees. These characteristics imply that 4QRP contains deliberate reworking of biblical material that is in line with sectarian ideology, in contrast to a mere mechanical copying of the text. Though the scroll may not be strictly sectarian, at the very least, it is proto sectarian in that 4QRP served as source material for the community's ideol ogy.