August 20131

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Emancipating Modern Slaves: the Challenges of Combating the Sex

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2013 Emancipating Modern Slaves: The hC allenges of Combating the Sex Trade Rachel Mann Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Mann, Rachel, "Emancipating Modern Slaves: The hC allenges of Combating the Sex Trade" (2013). Honors Theses. 700. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/700 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMANCIPATING MODERN SLAVES: THE CHALLENGES OF COMBATING THE SEX TRADE By Rachel J. Mann * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Political Science UNION COLLEGE June, 2013 ABSTRACT MANN, RACHEL Emancipating Modern Slaves: The Challenges of Combating the Sex Trade, June 2013 ADVISOR: Thomas Lobe The trafficking and enslavement of women and children for sexual exploitation affects millions of victims in every region of the world. Sex trafficking operates as a business, where women are treated as commodities within a global market for sex. Traffickers profit from a supply of vulnerable women, international demand for sex slavery, and a viable means of transporting victims. Globalization and the expansion of free market capitalism have increased these factors, leading to a dramatic increase in sex trafficking. Globalization has also brought new dimensions to the fight against sex trafficking. -

Refugeemagazine

RefugeeIssue 11 Kakuma Edition Magazine KAKUMA JOINS THE WORLD IN CELEBRATING RIO 2016 The Refugee Magazine Issue 11 1 2 The Refugee Magazine Issue 11 Editorial Editorial know by now you all are aware that Kakuma’s best athletes competed with the world’s best at the 2016 Rio Olympic Games. Yes, you read that well. For the first time in history refugees have been represented in the Olympic games. The 10 refugees from around the world participated in the Olympics under the International Olympics Committee flag as they Ido not belong to any state. 5 out of the 10 refugees selected worldwide are from the Kakuma Refugee Camp. We share with you some of their stories and also what their families, relatives and close friends feel about their historic achievement. This month has also seen FilmAid International partner with International Olympic Committee, Amnesty International, Globecast, and UNHCR to screen the 2016 Rio Olympic Games live from Brazil to thousands of refugees living in the Kakuma Refugee Camp. The screening locations located at Kakuma 1 Sanitation and Kakuma 4 near Hope Primary School have attracted thousands of refugees some of whom are watching the Olympics for the first time. We share some of the funniest and best quotes from refugees who brave the cold night to support their own. In our fashion column this month, we take at a look at designers and designs that are trending in various communities or areas across the camp. Find out what you need to have in your wardrobe this season. Finally, in the spirit of the Olympic Games, we share stories of different sports men and women who might not have made it to the 2016 Rio Olympic games, but have a promising future ahead. -

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination

Recasting Caste: Histories of Dalit Transnationalism and the Internationalization of Caste Discrimination by Purvi Mehta A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Farina Mir, Chair Professor Pamela Ballinger Emeritus Professor David W. Cohen Associate Professor Matthew Hull Professor Mrinalini Sinha Dedication For my sister, Prapti Mehta ii Acknowledgements I thank the dalit activists that generously shared their work with me. These activists – including those at the National Campaign for Dalit Human Rights, Navsarjan Trust, and the National Federation of Dalit Women – gave time and energy to support me and my research in India. Thank you. The research for this dissertation was conducting with funding from Rackham Graduate School, the Eisenberg Center for Historical Studies, the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, the Center for Comparative and International Studies, and the Nonprofit and Public Management Center. I thank these institutions for their support. I thank my dissertation committee at the University of Michigan for their years of guidance. My adviser, Farina Mir, supported every step of the process leading up to and including this dissertation. I thank her for her years of dedication and mentorship. Pamela Ballinger, David Cohen, Fernando Coronil, Matthew Hull, and Mrinalini Sinha posed challenging questions, offered analytical and conceptual clarity, and encouraged me to find my voice. I thank them for their intellectual generosity and commitment to me and my project. Diana Denney, Kathleen King, and Lorna Altstetter helped me navigate through graduate training. -

UNDP ERITREA NEWSLETTER Special Edition ©Undperitrea/Mwaniki

UNDP ERITREA NEWSLETTER Special Edition ©UNDPEritrea/Mwaniki UNDP Staff in Asmara, Eritrea In this Issue 3. New UN Secretary General Cooperation Framework 10. Ground breaking 6. Eritrean Students receive 2017-2015. International Conference 708 bicycles from Qhubeka 8. International Day for the on Eritrean Studies held in Asmara 7. Government of the Eradication of Poaverty State of Eritrea and the marked in Eritrea 11. Fifty years of development, United Nations launch 9. International Youth Day Eritrea celebrates UNDP’s the Strategic Partnership celebration in Eritrea 50th anniversary Message from the Resident Representative elcome to our special edition of the UNDP Eritrea annual newsletter. In this special edition, we shareW with our partners and the public some of our stories from Eritrea. From the beginning of this year, we embarked on a new Country Programme Document (CPD) and a new Strategic Partnership Cooperation Framework (SPCF) between the UN and The Government of the State of Eritrea. Both documents will guide our work until 2021. In February 2017, we partnered with the Ministry of Education, Qhubeka, Eritrea Commission of Culture and Sports and © UNDP Eritrea/Mwaniki the 50 mile Ride for Rwanda to bring 708 bicycles to students in Eritrea. This UNDP Eritrea RR promoting the SDGs to mark the 50th Anniversary initiative is an education empowerment program in Eritrea that has been going Framework (SPCF) 2017 – 2021 between In 2017, I encourage each one of us to on for 2 years. the UN and the Government of the State reflect on our successes and lessons of Eritrea. learned in the previous years. -

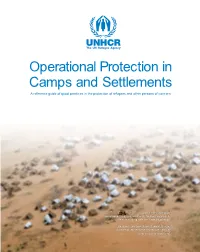

Operational Protection in Camps and Settlements

Operational Protection in Camps and Settlements Operational Protection in Camps and Settlements A reference guide of good practices in the protection of refugees and other persons of concern A UNHCR publication, developed in co-operation with the NGO community and with funding from the Ford Foundation. Solutions and Operations Support Section Division of International Protection Services Geneva, Switzerland 2006 Operational Protection in Camps and Settlements A Reference Guide of Good Practices in the Protection of Refugees and Other Persons of Concern Sudan / Internally displaced people / aerial view of Seliah camp, 150 km north of El Geneina. The camp has 10,000 IDPs, most of whom fled their villages between May and August 2003, after attacks from the Janjaweed; others recently came back from refugee camps in Eastern Chad. September 27, 2004. UNHCR / H. Caux The Operational Protection Reference Guide is published in loose-leaf binder format to allow the periodic update and addition of good practices and new guidance. These supplements will be distributed regularly, with new Table of Contents and instructions on addition to the Reference Guide. Limited additional information and documents may be available for some of the good practices herein. NGOs and UNHCR field offices looking to replicate such practices, in ways appropriate to their local context, are encouraged to contact the UNHCR field office or NGO listed in the good practice for further information, including updates and lessons learned that have emerged since publication. UNHCR is always eager to receive additional examples of good practices from NGOs, refugee communities and UNHCR field offices, for possible inclusion in future supplements to the Guide. -

Farley Prostitution, Sex Trade, COVID-19 Pandemic

1 Prostitution, the Sex Trade, and the COVID-19 Pandemic by Melissa Farley [1] Logos - a journal of modern society & culture Spring 2020 Volume 19 #1 The COVID-19 pandemic has had immediate and severe impacts on women in the sex trade who are already among the most vulnerable women on the planet. Because of quarantines, social distancing, governments’ neglect of the poor, systemic racism in all walks of life including healthcare, failure to protect children from abuse, and the predation of sex buyers and pimps – the coronavirus pandemic threatens already-marginalized women’s ability to survive. Even before the pandemic, sex buyers and pimps inflicted more sexual violence on women in the sex trade than any other group of women who have been studied by researchers (Hunter, 1994; Farley, 2017). The greater the poverty, the greater the likelihood of violent exploitation in the sex trade, as noted 26 years ago by Dutch researcher Ine Vanwesenbeeck (1994). This article will discuss the impact of COVID-19 as it increases harms resulting from the poverty and violent exploitation of prostitution, an oppressive institution built on foundations of sexism and racism. Women in the sex trade are in harm’s way for many reasons including a lack of food, shelter, and healthcare, all of which increase their risk of contracting COVID19. Understanding what it’s like to be anxious about access to food and shelter is key to understanding the risks taken by people in prostitution. Knowing they were risking their lives, many women prostituted during the pandemic. “Poverty will kill us before the coronavirus,” said an Indian woman in prostitution (Dutt, 2020). -

Desert Locust Swarm in Northern Red Sea Region Soil and Water Conservation Crops in Halhal Sub-Zone in Good Condition

Special Edition No. 25 Saturday, August 29, 2020 Pages 4 DESERT LOCUST SWARM IN NORTHERN RED SEA REGION SOIL AND WATER CONSERVATION The administrator of Foro sub- ready for distribution to farmers, zone, Mr. Osman Arafa, called on Mr. Tesfay Tewolde, head of the the residents to finalize preparation Ministry of Agriculture branch in for the water and soil conservation the sub-zone, called on the farmers program that is set to begin in the to finalize preparation and the coming month of September. administrations to submit request for agricultural machinery service. Mr. Osman made the call at a meeting he conducted with Pointing out that effort is administrators and managing underway to put under control directors as well as village locust swarm migrating from coordinators of the administrative neighboring countries, Mr. Osman areas of Zula, Afta, Hadish called on the residents to stay Airomale, Malka and Roberia. vigilant and immediately report to concerned institutions in case of At the meeting, Mr. Osman new occurrence of locust swarm. indicated that the program will include construction of terraces and According to document from the water diversion schemes as well as Ministry of Agriculture in the sub- agricultural infrastructure. zone, in Foro sub-zone there is 83 Desert locust swarm originating to 80 hectares of land, Mr. Tesfit on controlling desert locust swarm Indicating that select seeds are hectares of arable land. from neighboring countries of Gerezgiher from the Ministry of invasion. Ethiopia and Yemen has been Agriculture branch in the region detected in small scale in some said that the swarm is spreading to areas of the Northern Red Sea other areas and that strong effort Region. -

East and Horn of Africa

EAST AND HORN OF AFRICA 2014 - 2015 GLOBAL APPEAL Chad Djibouti Eritrea Ethiopia Kenya Somalia South Sudan Sudan Uganda Distribution of food tokens to Sudanese refugees in Yida, South Sudan (May 2012) UNHCR / V. TAN | Overview | Working environment The East and Horn of Africa continues to The situation in Sudan remains complex. against human smuggling and trafficking suffer from conflict and displacement. Violence in South Kordofan and Blue in eastern Sudan, more effort is required While the number of people in the region Nile States, as well as in parts of Darfur, to protect people of concern in the east requiring humanitarian assistance has risen has sent refugees fleeing into several against exploitation and violence. significantly, access to those in need is neighbouring countries. In 2013, conflict often impeded. Some 6 million people of between ethnic groups over mining rights, In South Sudan, inter-ethnic conflict in concern to UNHCR, including 1.8 million and a general breakdown in law and order Jonglei State has displaced thousands of refugees and more than 3 million internally in the Darfur region of Sudan, resulted in people. Refugees have fled into Ethiopia displaced people (IDPs), require protection loss of life as well as displacement both and Kenya and, to a lesser extent, Uganda. and assistance in the region. internally and externally. Thousands of The lack of security is one of the main refugees have streamed into neighbouring obstacles to access and humanitarian However, there has been some improvement eastern Chad in search of protection. intervention in this region of South Sudan. in the situation in Somalia, leading to fewer Hundreds of thousands more have been refugees fleeing the country and prompting internally displaced, reversing, in the space Kenya remains the largest refugee-hosting some to return. -

Regrouping of Villages News Brief Improving Health Service Commendable Effort Has Been Made to Improve and Expand Health Service Provision in the Southern Region

Special Edition No. 82 Saturday, 3 April, 2021 Pages 4 REGROUPING OF VILLAGES NEWS BRIEF IMPROVING HEALTH SERVICE Commendable effort has been made to improve and expand health service provision in the Southern region. According to Dr. Emanuel Mihreteab, head of the Ministry of Health branch in the region, in 2020 modern medical equipment have been installed in five hospitals in the region and that praiseworthy medical service is being provided to the public. Indicating that the health facilities are equipped with the necessary medical equipment and human resources, Dr. Emanuel said that compared to that of 2019 pre and post natal treatment visits has increased by 64%, pregnant women delivering at health facilities by 3% and vaccination coverage by 94%. Social service provision are significantly contributing Foro semi-urban center is Dr. Emanuel went on to say that controlling communicable diseases institutions put in place in Foro in facilitating socio-economic located 46 km south of the port has been the main priority program and that malaria infection has been semi-urban center is contributing activities, the residents called for city of Massawa and is resident reduced by 50% and death rate due to malaria has been reduced to zero in villages regrouping. the maintenance of the roads in to about 800 families. level while TB treatment to 93%. some areas that are damaged due The substantial investment to flooding and for allotment of In the Southern region there are one referral hospital, 4 hospitals, 3 made to put in place educational land for construction of residential community hospitals, 9 health centers, 41 health stations as well as 2 and health facilities as well as houses. -

Interaction Member Activity Report ETHIOPIA and ERITREA a Guide to Humanitarian and Development Efforts of Interaction Member Agencies in Ethiopia and Eritrea

InterAction Member Activity Report ETHIOPIA AND ERITREA A Guide to Humanitarian and Development Efforts of InterAction Member Agencies in Ethiopia and Eritrea October 2005 Photo courtesy of GOAL Produced by Joshua Kearns With the Humanitarian Policy and Practice Unit of 1717 Massachusetts Ave., NW, Suite 701, Washington DC 20036 Phone (202) 667-8227 Fax (202) 667-8236 Website: http://www.interaction.org Table of Contents Map of Ethiopia 4 Map of Eritrea 5 Background Summary 6 Report Summary 8 Organizations by Country 9 Organizations by Sector Activity 10 Glossary of Acronyms 13 InterAction Member Activity Report Action Against Hunger USA 15 Adventist Development and Relief Agency 18 Africare 21 AmeriCares 22 CARE 23 Catholic Relief Services 25 Christian Children’s Fund 29 Christian Reformed World Relief Committee 32 Church World Service 34 Concern Worldwide 36 Food for the Hungry International 42 International Institute of Rural Reconstruction 43 International Medical Corps 45 International Rescue Committee 49 Jesuit Refugee Services 52 Latter-day Saint Charities 54 Lutheran World Relief 55 InterAction Member Activity Report for Ethiopia and Eritrea 2 October 2005 Mercy Corps 56 Near East Foundation 58 Oxfam America 60 Pact, Inc 62 Pathfinder International 65 Save the Children 67 U.S. Fund for UNICEF 70 Winrock International 73 World Concern 75 World Vision 76 InterAction Member Activity Report for Ethiopia and Eritrea 3 October 2005 MAP OF ETHIOPIA Map courtesy of Central Intelligence Agency / World Fact Book InterAction Member Activity Report for Ethiopia and Eritrea 4 October 2005 MAP OF ERITREA Map courtesy of Central Intelligence Agency / World Fact Book InterAction Member Activity Report for Ethiopia and Eritrea 5 October 2005 BACKGROUND SUMMARY Introduction According to the United Nations Development Programme, Ethiopia and Eritrea rank 170th and 156th respectively out of 177 countries listed in the 2004 Human Development Report. -

Profile of Internal Displacement : Eritrea

PROFILE OF INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT : ERITREA Compilation of the information available in the Global IDP Database of the Norwegian Refugee Council (as of 19 October, 2001) Also available at http://www.idpproject.org Users of this document are welcome to credit the Global IDP Database for the collection of information. The opinions expressed here are those of the sources and are not necessarily shared by the Global IDP Project or NRC Norwegian Refugee Council/Global IDP Project Chemin Moïse Duboule, 59 1209 Geneva - Switzerland Tel: + 41 22 788 80 85 Fax: + 41 22 788 80 86 E-mail : [email protected] CONTENTS CONTENTS 1 PROFILE SUMMARY 6 SUMMARY 6 SUMMARY 6 CAUSES AND BACKGROUND OF DISPLACEMENT 9 MAIN CAUSES FOR DISPLACEMENT 9 ARMED CONFLICT BETWEEN ERITREA AND ETHIOPIA CAUSED SUBSTANTIAL INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT (MAY 1998 - JUNE 2000) 9 BACKGROUND OF THE CONFLICT 10 BACKGROUND TO THE BORDER DISPUTE (1999) 10 CHRONOLOGY OF THE MILITARY CONFRONTATIONS IN BORDER AREAS BETWEEN ERITREA AND ETHIOPIA (MAY 1998 – JUNE 2000) 11 END OF WAR AFTER SIGNING OF CEASE-FIRE IN JUNE 2000 AND PEACE AGREEMENT IN DECEMBER 2000 13 THE UNITED NATIONS MISSION IN ETHIOPIA AND ERITREA (UNMEE) AND THE TEMPORARY SECURITY ZONE (TSZ) 16 POPULATION PROFILE AND FIGURES 19 TOTAL NATIONAL FIGURES 19 BETWEEN 50,000-70,000 PEOPLE REMAINED INTERNALLY DISPLACED BY MID-2001 19 AVAILABLE FIGURES SUGGEST THAT 308,000 REMAINED INTERNALLY DISPLACED BY END-2000 20 APPROXIMATELY 900,000 ERITREANS INTERNALLY DISPLACED BY MID-2000 21 THE IDP POPULATION ESTIMATED TO AMOUNT TO 266,200 BY THE -

YOUTH INCLUSION: SIMAMA TV SHOW Youth in Daadab Refugee Camp Simama! to Voice Their Concerns

THE RefugeeMAGAZINE Dadaab Edition ISSUE #7 SCAN THIS QR CODE FOR ONLINE VERSION FOCUS ON YOUTH INCLUSION: SIMAMA TV SHOW Youth In Daadab Refugee Camp Simama! To Voice Their Concerns RefugeeTHE Editorial ear ardent readers, it is our joy that just as we bid farewell to 2015 with the 16 DAYS OF ACTIVISM SPECIAL EDITION of The Refugee IN BRIEF... Magazine, we are here yet again to usher Din 2016 with this 7th Edition telling interesting and SIMAMA! inspiring stories from the Dadaab complex. We also ACCEPT ME AS I AM capture the landmark production of a Television show focusing on Youth Inclusion that was produced here in Youth inclusion Campaign Dadaab by UNHCR in collaboration withFilmAid. In December 2015, FilmAid undertook a pioneering television production in the In this edition we relive the Activitie leading to and part Dadaab refugee camp. Simama - ACCEPT of the 16 Days of Activism whose culmination coincided ME AS I AM identified 50 young people from with the graduation ceremony of Filmid trained different demographics and assembled them Journalism Trainees . for a constructive discussion. Simama, Kiswahili translation for Arise Or FilmAid recruits and conducts annual training of youths Stand Up, is calling on the young refugees in Film Making and Journalism equiping them with the and the Dadaab community in general to skills to be able to tell their own stories in creative ways identify, speak up and construct a sustainable across print and film media. The 16 Days of Action run future for religious and cultural acceptance. from 25th November-10th December. The campaign spans these 16 Days in order to highlight the link Refugee Education: between violence against women and human rights.