Kalahari-Namib Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Actas Del Vi Simposio De La Red Latinoamericana De Estudios Sobre Imagen, Identidad Y Territorio

ACTAS DEL VI SIMPOSIO DE LA RED LATINOAMERICANA DE ESTUDIOS SOBRE IMAGEN, IDENTIDAD Y TERRITORIO “ESCENARIOS DE INQUIETUD. CIUDADES, POÉTICAS, POLÍTICAS” 14, 15 Y 16 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2016 MICAELA CUESTA M. FERNANDA GONZÁLEZ MARÍA STEGMAYER (COMPS.) 2 Cuesta, Micaela Actas del VI Simposio de la Red Latinoamericana de estudios sobre Imagen, Identidad y Territorio : escenarios de inquietud : ciudades, poéticas, políticas / Micaela Cuesta ; María Fernanda González ; María Stegmayer. - 1a ed compendiada. - Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires : Departamento de Publicaciones de la Facultad de Derecho y Ciencias Sociales de la Universidad de Buenos Aires. Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani - UBA, 2016. Libro digital, PDF Archivo Digital: descarga y online ISBN 978-987-3810-27-5 1. Identidad. 2. Imagen. 3. Actas de Congresos. I. González, María Fernanda II. Stegmayer, María III. Título CDD 306 3 ÍNDICE Presentación .............................................................................................................................. 5 Ciudades y memorias Sesión de debates I: Cuerpo y espacio Ciudades performativas: Teatralidad, memoria y experiencia..................................................... 11 Lorena Verzero Fioravante e o vazio: o desenho como estratégia de ausência................................................... 21 Eduardo Vieira da Cunha Percepción geográfica del espacio y los cuatro elementos: Reflexión sobre una interfaz entre fenomenología y astrología......................................................................................................... -

One of Five West Coast, Low-Latitude Deserts of the World, the Namib Extends Along the Entire Namibian Coastline in an 80-120 Km Wide Belt

N A M I B I A G 3 E 0 O 9 1 L - O Y G E I V C R A U S L NAMIB DESERT Source: Roadside Geology of Namibia One of five west coast, low-latitude deserts of the world, the Namib extends along the entire Namibian coastline in an 80-120 km wide belt. Its extreme aridity is the result of the cold, upwelling Benguela Current, which flows up the west coast of Africa as far as Angola, and because of its low temperatures induces very little evaporation and rainfall (<50 mm per year). It does, however, create an up to 50 km wide coastal fog belt providing sufficient moisture for the development of a specialist flora and fauna, many of which are endemic to the Namib. In addition, the lagoons at Walvis Bay and Sandwich Harbour are designated wetlands of international importance, because of their unique setting and rich birdlife, including flamingo, white pelican and Damara tern. Larger mammals like the famed desert elephant, black rhino, lion, cheetah and giraffe can be found along the northern rivers traversing the Skeleton Coast National Park. Geomorphologically, the Namib includes a variety of landscapes, including classic sand dunes, extensive gravel plains, locally with gypcrete and calcrete duricrusts, elongated salt pans, ephemeral watercourses forming linear oases, inselbergs and low mountain ranges. Along the coast, wind-swept sandy beaches alternate with rocky stretches, in places carved into striking rock formations (e.g. Bogenfels Arch). Designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2013, the “Namib Sand Sea“ between Lüderitz and the Kuiseb River encompasses such well-known landmarks as Sossusvlei and Sandwich Harbour, while the fabled Skeleton Coast north of the Ugab River is notorious for its numerous ship wrecks. -

Explore the Northern Cape Province

Cultural Guiding - Explore The Northern Cape Province When Schalk van Niekerk traded all his possessions for an 83.5 carat stone owned by the Griqua Shepard, Zwartboy, Sir Richard Southey, Colonial Secretary of the Cape, declared with some justification: “This is the rock on which the future of South Africa will be built.” For us, The Star of South Africa, as the gem became known, shines not in the East, but in the Northern Cape. (Tourism Blueprint, 2006) 2 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module # 1 - Province Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Province Overview Module # 2 - Cultural Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Cultural Overview Module # 3 - Historical Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Historical Overview Module # 4 - Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Component # 1 - Northern Cape Wildlife and Nature Conservation Overview Module # 5 - Namaqualand Component # 1 - Namaqualand Component # 2 - The Hantam Karoo Component # 3 - Towns along the N14 Component # 4 - Richtersveld Component # 5 - The West Coast Module # 5 - Karoo Region Component # 1 - Introduction to the Karoo and N12 towns Component # 2 - Towns along the N1, N9 and N10 Component # 3 - Other Karoo towns Module # 6 - Diamond Region Component # 1 - Kimberley Component # 2 - Battlefields and towns along the N12 Module # 7 - The Green Kalahari Component # 1 – The Green Kalahari Module # 8 - The Kalahari Component # 1 - Kuruman and towns along the N14 South and R31 Northern Cape Province Overview This course material is the copyrighted intellectual property of WildlifeCampus. It may not be copied, distributed or reproduced in any format whatsoever without the express written permission of WildlifeCampus. 3 – WildlifeCampus Cultural Guiding Course – Northern Cape Module 1 - Component 1 Northern Cape Province Overview Introduction Diamonds certainly put the Northern Cape on the map, but it has far more to offer than these shiny stones. -

Sand Dunes Computer Animations and Paper Models by Tau Rho Alpha*, John P

Go Home U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Sand Dunes Computer animations and paper models By Tau Rho Alpha*, John P. Galloway*, and Scott W. Starratt* Open-file Report 98-131-A - This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this program has been used by the U.S. Geological Survey, no warranty, expressed or implied, is made by the USGS as to the accuracy and functioning of the program and related program material, nor shall the fact of distribution constitute any such warranty, and no responsibility is assumed by the USGS in connection therewith. * U.S. Geological Survey Menlo Park, CA 94025 Comments encouraged tralpha @ omega? .wr.usgs .gov [email protected] [email protected] (gobackward) <j (goforward) Description of Report This report illustrates, through computer animations and paper models, why sand dunes can develop different forms. By studying the animations and the paper models, students will better understand the evolution of sand dunes, Included in the paper and diskette versions of this report are templates for making a paper models, instructions for there assembly, and a discussion of development of different forms of sand dunes. In addition, the diskette version includes animations of how different sand dunes develop. Many people provided help and encouragement in the development of this HyperCard stack, particularly David M. Rubin, Maura Hogan and Sue Priest. -

Back Matter (PDF)

Index Page numbers in italic refer to tables, and those in bold to figures. accretionary orogens, defined 23 Namaqua-Natal Orogen 435-8 Africa, East SW Angola and NW Botswana 442 Congo-Sat Francisco Craton 4, 5, 35, 45-6, 49, 64 Umkondo Igneous Province 438-9 palaeomagnetic poles at 1100-700 Ma 37 Pan-African orogenic belts (650-450 Ma) 442-50 East African(-Antarctic) Orogen Damara-Lufilian Arc-Zambezi Belt 3, 435, accretion and deformation, Arabian-Nubian Shield 442-50 (ANS) 327-61 Katangan basaltic rocks 443,446 continuation of East Antarctic Orogen 263 Mwembeshi Shear Zone 442 E/W Gondwana suture 263-5 Neoproterozoic basin evolution and seafloor evolution 357-8 spreading 445-6 extensional collapse in DML 271-87 orogenesis 446-51 deformations 283-5 Ubendian and Kibaran Belts 445 Heimefront Shear Zone, DML 208,251, 252-3, within-plate magmatism and basin initiation 443-5 284, 415,417 Zambezi Belt 27,415 structural section, Neoproterozoic deformation, Zambezi Orogen 3, 5 Madagascar 365-72 Zambezi-Damara Belt 65, 67, 442-50 see also Arabian-Nubian Shield (ANS); Zimbabwe Belt, ophiolites 27 Mozambique Belt Zimbabwe Craton 427,433 Mozambique Belt evolution 60-1,291, 401-25 Zimbabwe-Kapvaal-Grunehogna Craton 42, 208, 250, carbonates 405.6 272-3 Dronning Mand Land 62-3 see also Pan-African eclogites and ophiolites 406-7 Africa, West 40-1 isotopic data Amazonia-Rio de la Plata megacraton 2-3, 40-1 crystallization and metamorphic ages 407-11 Birimian Orogen 24 Sm-Nd (T DM) 411-14 A1-Jifn Basin see Najd Fault System lithologies 402-7 Albany-Fraser-Wilkes -

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018 Private Bag 0024 Gaborone TOLL FREE NUMBER: 0800600200 Tel: ( +267) 367 1300 Fax: ( +267) 395 2201 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Published by STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Phone: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Email: [email protected] Website: www.statsbots.org.bw Contact Unit: Environment Statistics Unit Phone: 367 1300 ISBN: 978-99968-482-3-0 (e-book) Copyright © Statistics Botswana 2020 No part of this information shall be reproduced, stored in a Retrieval system, or even transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronically, mechanically, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Statistics Botswana. BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS WATER DIGEST 2018 Statistics Botswana PREFACE This is Statistics Botswana’s annual Botswana Environment Statistics: Water Digest. It is the first solely water statistics annual digest. This Digest will provide data for use by decision-makers in water management and development and provide tools for the monitoring of trends in water statistics. The indicators in this report cover data on dam levels, water production, billed water consumption, non-revenue water, and water supplied to mines. It is envisaged that coverage of indicators will be expanded as more data becomes available. International standards and guidelines were followed in the compilation of this report. The United Nations Framework for the Development of Environment Statistics (UNFDES) and the United Nations International Recommendations for Water Statistics were particularly useful guidelines. The data collected herein will feed into the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) for water and hence facilitate an informed management of water resources. -

Early History of South Africa

THE EARLY HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES . .3 SOUTH AFRICA: THE EARLY INHABITANTS . .5 THE KHOISAN . .6 The San (Bushmen) . .6 The Khoikhoi (Hottentots) . .8 BLACK SETTLEMENT . .9 THE NGUNI . .9 The Xhosa . .10 The Zulu . .11 The Ndebele . .12 The Swazi . .13 THE SOTHO . .13 The Western Sotho . .14 The Southern Sotho . .14 The Northern Sotho (Bapedi) . .14 THE VENDA . .15 THE MASHANGANA-TSONGA . .15 THE MFECANE/DIFAQANE (Total war) Dingiswayo . .16 Shaka . .16 Dingane . .18 Mzilikazi . .19 Soshangane . .20 Mmantatise . .21 Sikonyela . .21 Moshweshwe . .22 Consequences of the Mfecane/Difaqane . .23 Page 1 EUROPEAN INTERESTS The Portuguese . .24 The British . .24 The Dutch . .25 The French . .25 THE SLAVES . .22 THE TREKBOERS (MIGRATING FARMERS) . .27 EUROPEAN OCCUPATIONS OF THE CAPE British Occupation (1795 - 1803) . .29 Batavian rule 1803 - 1806 . .29 Second British Occupation: 1806 . .31 British Governors . .32 Slagtersnek Rebellion . .32 The British Settlers 1820 . .32 THE GREAT TREK Causes of the Great Trek . .34 Different Trek groups . .35 Trichardt and Van Rensburg . .35 Andries Hendrik Potgieter . .35 Gerrit Maritz . .36 Piet Retief . .36 Piet Uys . .36 Voortrekkers in Zululand and Natal . .37 Voortrekker settlement in the Transvaal . .38 Voortrekker settlement in the Orange Free State . .39 THE DISCOVERY OF DIAMONDS AND GOLD . .41 Page 2 EVOLUTION OF AFRICAN SOCIETIES Humankind had its earliest origins in Africa The introduction of iron changed the African and the story of life in South Africa has continent irrevocably and was a large step proven to be a micro-study of life on the forwards in the development of the people. -

World Heritage Cultural Landscapes a Handbook for Conservation and Management

World Heritage papers26 World Heritage Cultural Landscapes A Handbook for Conservation and Management World Heritage Cultural Landscapes A Handbook for Conservation and Management Nora Mitchell, Mechtild Rössler, Pierre-Marie Tricaud (Authors/Ed.) Drafting group Nora Mitchell, Mechtild Rössler, Pierre-Marie Tricaud Editorial Assistant Christine Delsol Contributors Carmen Añón Feliú Alessandro Balsamo* Francesco Bandarin* Disclaimer Henry Cleere The ideas and opinions expressed in this publication are those of Viera Dvoráková the authors and are not necessarily those of UNESCO and do not Peter Fowler commit the Organization. Eva Horsáková Jane Lennon The designations employed and the presentation of material in this Katri Lisitzin publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever Kerstin Manz* on the part of UNESCO concerning the legal status of any country, Nora Mitchell territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delim- Meryl Oliver itation of its frontiers or boundaries. Saúl Alcántara Onofre John Rodger Published in November 2009 by the UNESCO World Heritage Centre Mechtild Rossler* Anna Sidorenko* The publication of this volume was financed by the Netherlands Herbert Stovel Fund-in-Trust. Pierre-Marie Tricaud Herman van Hooff* Augusto Villalon World Heritage Centre Christopher Young UNESCO (* UNESCO staff) 7, place de Fontenoy 75352 Paris 07 SP France Coordination of the World Heritage Paper Series Tel. : 33 (0)1 45 68 15 71 Vesna Vujicic Lugassy Fax: 33 (0)1 45 68 55 70 Website: http://whc.unesco.org -

Upper Mantle P and S Wave Velocity Structure of the Kalahari Craton And

RESEARCH LETTER Upper Mantle P and S Wave Velocity Structure of the 10.1029/2019GL084053 Kalahari Craton and Surrounding Proterozoic Key Points: • Thick cratonic lithosphere extends Terranes, Southern Africa beneath the Rehoboth Province and Kameron Ortiz1, Andrew Nyblade1,5 , Mark van der Meijde2, Hanneke Paulssen3 , parts of the northern Okwa Terrane 4 4 5 2,6 and Magondi Belt Motsamai Kwadiba , Onkgopotse Ntibinyane , Raymond Durrheim , Islam Fadel , • The northern edge of the greater and Kyle Homman1 Kalahari Craton lithosphere lies along the northern boundary of the 1Department of Geosciences, Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, USA, 2Faculty for Geo‐information Rehoboth Province and Magondi Science and Earth Observation (ITC), University of Twente, Enschede, Netherlands, 3Department of Earth Sciences, Belt 4 • Cratonic mantle lithosphere Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University, Utrecht, Netherlands, Botswana Geoscience Institute, Lobatse, Botswana, 5 6 beneath the Okwa Terrane and School of Geosciences, The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, Geology Department, Faculty Magondi Belt may have been of Science, Helwan University, Ain Helwan, Egypt chemically altered by Proterozoic magmatic events Abstract New broadband seismic data from Botswana and South Africa have been combined with Supporting Information: existing data from the region to develop improved P and S wave velocity models for investigating the • Supporting Information S1 upper mantle structure of southern Africa. Higher craton‐like velocities are imaged beneath the Rehoboth Province and parts of the northern Okwa Terrane and the Magondi Belt, indicating that the Correspondence to: northern edge of the greater Kalahari Craton lithosphere lies along the northern boundary of these A. Nyblade, terranes. -

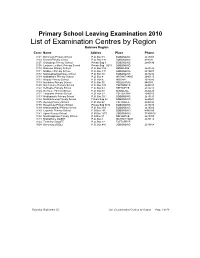

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

Pinnacle Point Cave 13B (Western Cape Province, South Africa) in Context: the Cape Floral Kingdom, Shellfish, and Modern Human Originsq

Journal of Human Evolution 59 (2010) 425e443 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Human Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhevol Pinnacle Point Cave 13B (Western Cape Province, South Africa) in context: The Cape Floral kingdom, shellfish, and modern human originsq Curtis W. Marean Institute of Human Origins, School of Human Evolution and Social Change, P.O. Box 872402, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-2402, USA article info abstract Article history: Genetic and anatomical evidence suggests that Homo sapiens arose in Africa between 200 and 100 ka, Received 15 December 2009 and recent evidence suggests that complex cognition may have appeared between w164 and 75 ka. This Accepted 19 March 2010 evidence directs our focus to Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 6, when from 195e123 ka the world was in a fluctuating but predominantly glacial stage, when much of Africa was cooler and drier, and when dated Keywords: archaeological sites are rare. Previously we have shown that humans had expanded their diet to include Middle Stone Age marine resources by w164 ka (Æ12 ka) at Pinnacle Point Cave 13B (PP13B) on the south coast of South Mossel Bay Africa, perhaps as a response to these harsh environmental conditions. The associated material culture Origins of modern humans documents an early use and modification of pigment, likely for symbolic behavior, as well as the production of bladelet stone tool technology, and there is now intriguing evidence for heat treatment of lithics. PP13B also includes a later sequence of MIS 5 occupations that document an adaptation that increasingly focuses on coastal resources. -

Developing a Framework of Dune Accumulation in the Northern Rub Al

Developing a framework of Quaternary dune accumulation in the northern Rub’ al-Khali, Arabia. Andrew R Farranta, Geoff A T Dullerb, Adrian G Parkerc, Helen M Robertsb, Ash Partond, Robert W O Knoxa#, and Thomas Bidea. aBritish Geological Survey, Keyworth, Nottingham, NG12 5GG, UK. [email protected] [corresponding author 0115 9363184]. bAberystwyth Luminescence Research Laboratory, Department of Geography & Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Aberystwyth, SY23 3DB, Wales, UK cDepartment of Social Sciences, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Oxford Brookes University, Oxford, OX3 0BP, UK dResearch Laboratory for Archaeology and the History of Art, School of Archaeology, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX1 2HU, UK #Deceased Abstract Located at the crossroads between Africa and Eurasia, Arabia occupies a pivotal position for human migration and dispersal during the Late Pleistocene. Deducing the timing of humid and arid phases is critical to understanding when the Rub’ al-Khali desert acted as a barrier to human movement and settlement. Recent geological mapping in the northern part of the Rub’ al-Khali has enabled the Quaternary history of the region to be put into a regional stratigraphical framework. In addition to the active dunes, two significant palaeodune sequences have been identified. Dating of key sections has enabled a chronology of dune accretion and stabilisation to be determined. In addition, previously published optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dates have been put in their proper stratigraphical context, from which a record of Late Pleistocene dune activity can be constructed. The results indicate the record of dune activity in the northern Rub’ al-Khali is preservation limited and is synchronous with humid events driven by the incursion of the Indian Ocean monsoon.