Turning a Blind Eye: Why Washington Keeps Giving in to Wall Street

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

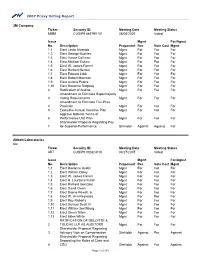

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM

2007 Proxy Voting Report 3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/08/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Rozanne Ridgway Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Supermajority 3 Voting Requirements Mgmt For For For Amendment to Eliminate Fair-Price 4 Provision Mgmt For For For 5 Executive Annual Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Approve Material Terms of 6 Performance Unit Plan Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Pay- 7 for-Superior-Performance ShrHoldr Against Against For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/27/2007 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect Richard Gonzalez Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. -

September 23–24, 2020

Wednesday, Thursday, On Demand Sponsors September 23 September 24 Sessions A gathering for regulators and industry professionals to exchange ideas and empower success September 23–24, 2020 Wednesday, September 23 LIVE 10:00 AM – 11:00 AM – LIVE: Virtual Exhibit Hall During this allotted time, visit sponsors, ask questions, and learn from fellow colleagues about industry topics. 11:00 AM – 11:05 AM – LIVE: Welcome Remarks C&L VIRTUAL FORUM CHAIRPERSON Scott Kursman Citi 11:05 AM – 11:35 AM – LIVE: One-on-One Conversation with Robert Cook Robert Cook MODERATOR FINRA Ira D. Hammerman SIFMA 11:45 AM – 12:45 PM – LIVE: COVID-19: Lessons Learned for Compliance & Legal Professionals • Operational capacity – what does this mean for systems access, especially trading businesses • Meeting regulatory obligations for oversight in this COVID-19 environment. Anticipating unique risks in this new operating structure. • Supervisory and management challenges with remote staff and related information security challenges • Discuss today’s challenges of internal and external communications and recordkeeping • Considerations for Return-to-Work plans Michael Broadbery Andy Cadel Kevin H. Dunn Marlon Paz Emily Westerberg MODERATOR Goldman Sachs Citi National Institute for Mayer Brown Russell Amy J. Greer Occupational Safety SEC Baker & McKenzie LLP and Health 12:55 PM – 2:00 PM – LIVE: Leadership Matters: Meaningful, Measured Impact in Diversity and Inclusion This panel will take a deeper dive into how today’s financial industry leadership work must be a matter -

Report of Investigation

REPORT OF INVESTIGATION UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL Investigation into Allegations of Improper Preferential Treatment and Special Access in Connection with the Division of Enforcement's Investigation of Citigroup, Inc. Case No. OIG-559 September 27,2011 This document is subjed to the provisions of th e Privacy Act of 1974, and may require redadion before disdosure to third parties. No redaction has betn performed by the Office of Inspedor Gmeral. Recipients of this report should not disseminate or copy it without the Inspector General's approval. " Report of Investigation Cas. No. OIG-559 Investigation into Allegations of Improper Preferential Treatment and Speeial Access in Connection with the Division of Enforcement's Investigation ofCitigroup, Inc. Table of Contents Introduction and Summary of Results ofthe Investigation ......................................... ..... .. I Scope of the Investigation................................................................................................... 2 Relevant Statutes, Regulations and Pol icies ....................................................................... 4 Results of the Investigation................................................. .. .............................................. 5 I. The Enforcement Staff Investigated Citigroup and Considered Various Charges and Settlement Options ........................................................................................... 5 A. The Enforcement Staff Opened an Investigation -

The TJX Companies, Inc. (Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

Table of Contents SCHEDULE 14A INFORMATION Proxy Statement Pursuant to Section 14(a) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (Amendment No. ) Filed by the Registrant x Filed by a Party other than the Registrant o Check the appropriate box: x Preliminary Proxy Statement o Definitive Proxy Statement o Definitive Additional Materials o Soliciting Material Pursuant to §240.14a-11(c) or §240.14a-12 o Confidential, for Use of the Commission Only (as permitted by Rule 14a-6(e)(2)) The TJX Companies, Inc. (Name of Registrant as Specified In Its Charter) (Name of Person(s) Filing Proxy Statement) Payment of Filing Fee (Check the appropriate box): x No fee required. o Fee computed on table below per Exchange Act Rules 14a-6(i)(1) and 0-11. 1) Title of each class of securities to which transaction applies: 2) Aggregate number of securities to which transaction applies: 3) Per unit price or other underlying value of transaction computed pursuant to Exchange Act Rule 0-11 (Set forth the amount on which the filing fee is calculated and state how it was determined): 4) Proposed maximum aggregate value of transaction: 5) Total fee paid: o Fee paid previously with preliminary materials. o Check box if any part of the fee is offset as provided by Exchange Act Rule 0-11(a)(2) and identify the filing for which the offsetting fee was paid previously. Identify the previous filing by registration statement number, or the Form or Schedule and the date of its filing. 1) Amount Previously Paid: 2) Form, Schedule or Registration Statement No.: 3) Filing Party: 4) Date Filed: Table of Contents 770 Cochituate Road Framingham, Massachusetts 01701 April , 2005 Dear Stockholder: We cordially invite you to attend our 2005 Annual Meeting on Tuesday, June 7, 2005, at 11:00 a.m., to be held in The Ben Cammarata Auditorium, located at our offices, 770 Cochituate Road, Framingham, Massachusetts. -

Lbex-Am 008597

CITIGROUP AGENDA Meeting Bank Participants Address Lehman's operating performance and risk management practices. • Introduce Brian Leach, CRO, who is new at Citi and in his role, to Ian and Paolo, as well as to the Firm. LBEX-AM 008597 CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS, INC. Lehman Agenda NETWORK MANAGEMENT • Citi is ranked #1 in Asia, #2 in the US, and #3 in Europe in total operating fees paid by LEH. Fees exceed $30 MM p.a. Citi has been# 1 on the short list to be awarded new operating business due to to the substantial credit support provided until its action of June 12. Most recently, Citi was awarded our Brazilian outsourcing. Brian R. Leach Chief Risk Officer Citi Brian Leach assumed the role of Chief Risk Officer in March 2008, reporting to Citi's Chief Executive Officer, Vikram Pandit. Brian is also the acting Chief Risk Officer for the Institutional Clients Group. Citi is a leading global financial services company and has a presence in more than 100 countries, representing 90% of the world's GOP. The Citi brand is the most recognized in the financial services industry. Citi is known around the world for market leadership, global product excellence, outstanding talent, strong regional and product franchises, and commitment to providing the highest-quality service to its clients. Prior to becoming Citi's Chief Risk Officer, Brian was the co-COO of Old Lane. Brian, along with several former colleagues from Morgan Stanley, founded Old Lane LP in 2005. Earlier, he had worked for his LBEX-AM 008598 CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY LEHMAN BROTHERS HOLDINGS, INC. -

SEC Historical Society Highlights

Securities and Exchange Commission Historical Society o Highlights of 2005 Preserving Investing’s Past WWW. SECHISTORICAL. ORG Exploring Investing’s Future T the virtual museum of sec and securities industry history T Highlights of 2005 Report The Highlights of 2005 is the narrative section of the Securities and Exchange Commission Historical Society’s 2005 Annual Report. The 2005 financial statement and list of donors Letter from the President will be published in the 2005 Annual Report later in 2006. Dear Friends: Carla L. Rosati, CFRE, Editor On December 1st, our virtual museum and archive at www.sechistorical.org Donald Norwood Design, Design and Publication opened its first galleries – 431 Days: Joseph P. Kennedy and the Creation of Scavone Photography and the SEC (1934-35); and William O. Douglas and the Growing Power of the Rob Tannenbaum, Photography SEC (1936-39) – a milestone in the mission of the Securities and Exchange (and images from the virtual museum and archive) Commission Historical Society to preserve and share SEC and securities history for generations to come. Securities and Exchange Commission For those of you who helped to build the Society as a non-profit organiza- Historical Society The Securities and Exchange Commission tion from our founding on September 15, 1999, and those of you who wit- Historical Society, a 501(c)(3) non-profit nessed the opening of the virtual museum and archive on June 1, 2002, this organization, independent of and separate was indeed a proud moment. from the U.S. Securities and Exchange When I met with SEC Chairman Christopher Cox in October, he informed Commission, preserves and shares SEC and me that the museum’s collections were used to prepare for his confirmation securities history through its virtual museum hearings. -

CORPORATIONS and CAPITAL MARKETS EVOLUTION Sponsored

CORPORATIONS AND CAPITAL MARKETS EVOLUTION Sponsored by: Columbia Law School Transactional Studies Program Speaker Biographies Raanan A. Agus Raanan A. Agus is the global head of the Principal Strategies Group in the Equities Division of Goldman Sachs. The Principal Strategies Group is a proprietary, multi-strategy investment arm within Goldman Sachs that engages in equity long/short strategies, convertible arbitrage, volatility strategies, distressed and capital structure arbitrage, tactical trading, and special situation/event-driven strategies. Mr. Agus joined Goldman Sachs in 1993 as an associate in Equities Arbitrage, and became a managing director in 1999 and a partner in 2000. Mr. Agus is also a member of the Equities/FICC Joint Operating Committee and the Firmwide Risk Committee. He is also on the Goldman Sachs chess team. Mr. Agus earned an A.B. degree from Princeton University in 1989 and a joint J.D./M.B.A. degree, specializing in finance, from Columbia University in 1993. Alan L. Beller Alan L. Beller is a partner based in the New York office of Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton. His practice focuses on a wide variety of complex securities, corporate governance, and corporate matters. Mr. Beller served as the Director of the Division of Corporation Finance of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and as Senior Counselor to the Commission from January 2002 until February 2006. During his four-year tenure, Mr. Beller led the Division in producing the most far-reaching corporate governance, financial disclosure, and securities offering reforms in Commission history, including the implementation of the corporate provisions of the Sarbanes- Oxley Act of 2002 and the adoption of corporate governance standards for listed companies. -

Q4 2007 Citigroup Inc. Earnings Conference Call on Jan. 15. 2008

FINAL TRANSCRIPT C - Q4 2007 Citigroup Inc. Earnings Conference Call Event Date/Time: Jan. 15. 2008 / 8:30AM ET www.streetevents.com Contact Us © 2008 Thomson Financial. Republished with permission. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of Thomson Financial. FINAL TRANSCRIPT Jan. 15. 2008 / 8:30AM, C - Q4 2007 Citigroup Inc. Earnings Conference Call CORPORATE PARTICIPANTS Art Tildesley Citigroup Inc. - IR Vikram Pandit Citigroup Inc. - CEO Gary Crittenden Citigroup Inc. - CFO CONFERENCE CALL PARTICIPANTS Guy Moszkowski Merrill Lynch - Analyst Betsy Graseck Morgan Stanley - Analyst William Tanona Goldman Sachs - Analyst Mike Mayo Deutsche Bank - Analyst Meredith Whitney Oppenheimer - Analyst Glenn Schorr UBS - Analyst Richard Bove Punk, Ziegel - Analyst David Hilder Bear Stearns - Analyst PRESENTATION Operator Good morning, ladies and gentlemen and welcome to Citi©s fourth-quarter and full-year 2007 earnings review featuring Citi Chief Executive Officer, Vikram Pandit and Chief Financial Officer, Gary Crittenden. Today©s call will be hosted by Art Tildesley. We ask that you hold all questions until the completion of the formal remarks at which time you will be given instructions for the question and answer session. Also, as a reminder, this conference is being recorded today. If you have any objections, please disconnect at this time. Mr. Tildesley, you may begin. Art Tildesley - Citigroup Inc. - IR Thank you very much, operator and thank you all for joining us this morning. Welcome to our fourth-quarter 2007 earnings presentation. The presentation that we will be walking through is available on our website, so you will want to download that now if you haven©t already done so. -

Printmgr File

Citigroup Inc. 399 Park Avenue New York, NY 10043 March 13, 2007 Dear Stockholder: We cordially invite you to attend Citigroup’s annual stockholders’ meeting. The meeting will be held on Tuesday, April 17, 2007, at 9AM at Carnegie Hall, 154 West 57th Street in New York City. The entrance to Carnegie Hall is on West 57th Street just east of Seventh Avenue. At the meeting, stockholders will vote on a number of important matters. Please take the time to carefully read each of the proposals described in the attached proxy statement. Thank you for your support of Citigroup. Sincerely, Charles Prince Chairman of the Board and Chief Executive Officer This proxy statement and the accompanying proxy card are being mailed to Citigroup stockholders beginning about March 13, 2007. Citigroup Inc. 399 Park Avenue New York, NY 10043 Notice of Annual Meeting of Stockholders Dear Stockholder: Citigroup’s annual stockholders’ meeting will be held on Tuesday, April 17, 2007, at 9AM at Carnegie Hall, 154 West 57th Street in New York City. The entrance to Carnegie Hall is on West 57th Street just east of Seventh Avenue. You will need an admission ticket or proof of ownership of Citigroup stock to enter the meeting. At the meeting, stockholders will be asked to ➢ elect directors, ➢ ratify the selection of Citigroup’s independent registered public accounting firm for 2007, ➢ act on certain stockholder proposals, and ➢ consider any other business properly brought before the meeting. The close of business on February 21, 2007 is the record date for determining stockholders entitled to vote at the annual meeting. -

Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets: Consultation Document

NOVEMBER 2020 TASKFORCE ON SCALING VOLUNTARY CARBON MARKETS CONSULTATION DOCUMENT REPORT FRONT-PIECE ABOUT THE TASKFORCE The Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets is a private sector-led initiative working to scale an effective and efficient voluntary carbon market to help meet the goals of the Paris Agreement. The Taskforce was initiated by Mark Carney, UN Special Envoy for Climate Action and Finance Advisor to UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson for the 26th UN Climate Change Conference of the Parties (COP26); is chaired by Bill Winters, Group Chief Executive, Standard Chartered; and sponsored by the Institute of International Finance (IIF) under the leadership of IIF President and CEO, Tim Adams. Annette Nazareth, a partner at Davis Polk and former Commissioner of the US Securities and Exchange Commission, serves as the Operating Lead for the Taskforce. McKinsey & Company provides knowledge and advisory support. The Taskforce’s more than 50 members represent buyers and sellers of carbon credits, standard setters, the financial sector and market infrastructure providers. The Taskforce’s unique value proposition has been to bring all parts of the value chain to work intensively together and to provide recommended actions for the most pressing pain-points facing voluntary carbon markets. The Taskforce is also supported by a highly engaged Consultation Group, composed of subject- matter experts from more than 80 institutions, who contribute additional perspective to the recommendations. ABOUT THE REPORT This report was developed by the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets, drawing on multiple sources, including a research collaboration with McKinsey & Company, which is providing knowledge and advisory support to the IIF. -

Citigroup Q3 2007 Earnings Call Transcript - Seeking Alpha Page 1 of 23

Citigroup Q3 2007 Earnings Call Transcript - Seeking Alpha Page 1 of 23 Citigroup Q3 2007 Earnings Call Transcript Citigroup, Inc. (C) Q3 2007 Earnings Call October 15, 20078:30 am ET Executives Art Tildesley - IR Charles Prince - Chairman, CEO Gary Crittenden - CFO Analysts Jason Goldberg - Lehman Brothers Betsy Graseck - Morgan Stanley Guy Moszkowski - Merrill Lynch Glenn Schorr - UBS John McDonald - Banc of AmericaSecurities Ron Mandle - GIC Mike Mayo - Deutsche Bank Meredith Whitney - CIBC World Markets Jeff Harte - Sandler O'Neill Vivek Juneja – JP Morgan Diane Merdian - KBW Operator Welcome to Citi's third quarter 2007 earnings reviewfeaturing Citi Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Charles Prince and ChiefFinancial Officer Gary Crittenden. Today's call will be hosted by ArtTildesley, Director of Investor Relations. (Operator Instructions) Mr.Tildesley, you may begin. Art Tildesley Thank you very much, operator and thank you all for joiningus today for our third quarter 2007 earnings presentation. We are going to walkyou through a presentation, that presentation is available on our website now,so if you haven't downloaded that, you want to do that now. The format we will follow will be Chuck will start the call,Gary will take you through our presentationand then we would be happy to answer any questions you may have. Before we get started, I would like to remind you thattoday's presentation may contain forward-looking statements. Citigroup'sfinancial results may differ materially from these statements, so please referto our SEC filings for a description of the factors that could cause our actualresults to differ from expectations. With that said, let me turn it over to Chuck. -

Credible Living Wills: the First Generation

CREDIBLE LIVING WILLS: THE FIRST GENERATION Davis Polk & Wardwell LLP and McKinsey & Company1 April 25, 2011 Executive Summary The post-financial crisis era has seen a paradigm shift in the regulation of the financial services industry. Systemically important financial institutions are becoming subject to new regulatory requirements in multiple areas including increased capital and liquidity requirements, mandatory stress tests, restrictions on their activities, higher prudential standards and recapitalization or wind-down mechanisms. Enhanced planning for the risk of failure is an important element of the new regulatory paradigm. Supervisors from the United States, the European Union and the Group of Twenty (G20) are developing requirements for systemically important financial institutions to create credible living wills. These plans will include key information about the firm and set forth actions that could be taken to reduce idiosyncratic losses and to mitigate systemic contagion in the event of financial distress, up to and including the insolvency or failure of the firm. In some ways, living wills are analogous to contingency planning for public emergencies that arise when a hurricane, earthquake or other natural disaster strikes. Even though human choices are the underlying causes of financial panics, financial panics are also like natural disasters because they have occurred repeatedly, suddenly, unpredictably and destructively throughout the history of financial markets. The rationale behind the living will is that, like contingency planning for an emergency, pre-planning could reduce the likelihood of future crises or at least enhance the ability of firms and supervisors to respond to a crisis. A concern with the living wills process is that, like a poorly designed contingency plan, it could be used to impose changes that are intended to reduce systemic risk but which are neither risk mitigating nor efficient.