The Evolutionary History of Cetacean Brain and Body Size

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Isthminia Panamensis, a New Fossil Inioid (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Chagres Formation of Panama and the Evolution of ‘River Dolphins’ in the Americas

Isthminia panamensis, a new fossil inioid (Mammalia, Cetacea) from the Chagres Formation of Panama and the evolution of ‘river dolphins’ in the Americas Nicholas D. Pyenson1,2, Jorge Velez-Juarbe´ 3,4, Carolina S. Gutstein1,5, Holly Little1, Dioselina Vigil6 and Aaron O’Dea6 1 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, USA 2 Departments of Mammalogy and Paleontology, Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, Seattle, WA, USA 3 Department of Mammalogy, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, CA, USA 4 Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA 5 Comision´ de Patrimonio Natural, Consejo de Monumentos Nacionales, Santiago, Chile 6 Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute, Balboa, Republic of Panama ABSTRACT In contrast to dominant mode of ecological transition in the evolution of marine mammals, different lineages of toothed whales (Odontoceti) have repeatedly invaded freshwater ecosystems during the Cenozoic era. The so-called ‘river dolphins’ are now recognized as independent lineages that converged on similar morphological specializations (e.g., longirostry). In South America, the two endemic ‘river dolphin’ lineages form a clade (Inioidea), with closely related fossil inioids from marine rock units in the South Pacific and North Atlantic oceans. Here we describe a new genus and species of fossil inioid, Isthminia panamensis, gen. et sp. nov. from the late Miocene of Panama. The type and only known specimen consists of a partial skull, mandibles, isolated teeth, a right scapula, and carpal elements recovered from Submitted 27 April 2015 the Pina˜ Facies of the Chagres Formation, along the Caribbean coast of Panama. -

Artiodactyla and Perissodactyla (Mammalia) from the Early-Middle Eocene Kuldana Formation of Kohat (Pakistan)

CO"uTK1BL 11015 FKOLI IHt \lC5tLL1 OF I' ALEO\ IOLOG1 THE UNIVERSITY OF IVICHIGAN VOI 77 Lo 10 p 717-37.1 October 33 1987 ARTIODACTYLA AND PERISSODACTYLA (MAMMALIA) FROM THE EARLY-MIDDLE EOCENE KULDANA FORMATION OF KOHAT (PAKISTAN) BY J. G. M. THEWISSEN. P. D. GINGERICH and D. E. RUSSELL MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ANN ARBOR CONTRIBUTIONS FROM THE MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY Charles B. Beck, Director Jennifer A. Kitchell, Editor This series of contributions from the Museum of Paleontology is a medium for publication of papers based chiefly on collections in the Museum. When the number of pages issued is sufficient to make a volume, a title page and a table of contents will be sent to libraries on the mailing list, and to individuals upon request. A list of the separate issues may also be obtained by request. Correspond- ence should be directed to the Museum of Paleontology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109. VOLS. II-XXVII. Parts of volumes may be obtained if available. Price lists are available upon inquiry. I ARTIODACTI L .-I A\D PERISSODACTYL4 (kl.iihlhlAL1A) FROM THE EARLY-h1IDDLE EOCEUE KCLD..I\4 FORMATIO\ OF KOHAT (PAKISTAY) J. G. M. THEWISSEN. P. D. GINGERICH AND D. E. RUSSELL Ah.strcict.-Chorlakki. yielding approximately 400 specimens (mostly isolated teeth and bone fragments). is one of four major early-to-middle Eocene niammal localities on the Indo-Pakistan subcontinent. On the basis of ung~~latesclescribed in this paper we consider the Chorlakki fauna to be younger than that from Barbora Banda. -

The Elephant Brain in Numbers

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 12 June 2014 NEUROANATOMY doi: 10.3389/fnana.2014.00046 The elephant brain in numbers Suzana Herculano-Houzel 1,2*, Kamilla Avelino-de-Souza 1,2, Kleber Neves 1,2, Jairo Porfírio 1,2, Débora Messeder 1,2, Larissa Mattos Feijó 1,2, José Maldonado 3 and Paul R. Manger 4 1 Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 2 Instituto Nacional de Neurociência Translacional, São Paulo, Brazil 3 MBF Bioscience, Inc., Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 4 School of Anatomical Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa Edited by: What explains the superior cognitive abilities of the human brain compared to other, larger Patrick R. Hof, Mount Sinai School of brains? Here we investigate the possibility that the human brain has a larger number of Medicine, USA neurons than even larger brains by determining the cellular composition of the brain of Reviewed by: the African elephant. We find that the African elephant brain, which is about three times John M. Allman, Caltech, USA 9 Roger Lyons Reep, University of larger than the human brain, contains 257 billion (10 ) neurons, three times more than the Florida, USA average human brain; however, 97.5%of the neurons in the elephant brain (251 billion) are *Correspondence: found in the cerebellum. This makes the elephant an outlier in regard to the number of Suzana Herculano-Houzel, Centro de cerebellar neurons compared to other mammals, which might be related to sensorimotor Ciências da Saúde, Universidade specializations. In contrast, the elephant cerebral cortex, which has twice the mass of the Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rua Carlos Chagas Filho, 373 – sala human cerebral cortex, holds only 5.6 billion neurons, about one third of the number of F1-009, Ilha do Fundão 21941-902, neurons found in the human cerebral cortex. -

How Welfare Biology and Commonsense May Help to Reduce Animal Suffering

Ng, Yew-Kwang (2016) How welfare biology and commonsense may help to reduce animal suffering. Animal Sentience 7(1) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1012 This article has appeared in the journal Animal Sentience, a peer-reviewed journal on animal cognition and feeling. It has been made open access, free for all, by WellBeing International and deposited in the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ng, Yew-Kwang (2016) How welfare biology and commonsense may help to reduce animal suffering. Animal Sentience 7(1) DOI: 10.51291/2377-7478.1012 Cover Page Footnote I am grateful to Dr. Timothy D. Hau of the University of Hong Kong for assistance. This article is available in Animal Sentience: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/ animsent/vol1/iss7/1 Animal Sentience 2016.007: Ng on Animal Suffering Call for Commentary: Animal Sentience publishes Open Peer Commentary on all accepted target articles. Target articles are peer-reviewed. Commentaries are editorially reviewed. There are submitted commentaries as well as invited commentaries. Commentaries appear as soon as they have been revised and accepted. Target article authors may respond to their commentaries individually or in a joint response to multiple commentaries. Instructions: http://animalstudiesrepository.org/animsent/guidelines.html How welfare biology and commonsense may help to reduce animal suffering Yew-Kwang Ng Division of Economics Nanyang Technological University Singapore Abstract: Welfare biology is the study of the welfare of living things. Welfare is net happiness (enjoyment minus suffering). Since this necessarily involves feelings, Dawkins (2014) has suggested that animal welfare science may face a paradox, because feelings are very difficult to study. -

EXTERNAL FEATURES of the DUSKY DOLPHIN Lagenorhynchus Obscurus (GRAY, 1828) from PERUVIAN WATERS Caracteristicas EXTERNAS DEL DE

Estud. Oceanol. 12: 37-53 1993 ISSN CL 0O71-173X EXTERNAL FEATURES OF THE DUSKY DOLPHIN Lagenorhynchus obscurus (GRAY, 1828) FROM PERUVIAN WATERS CARACTERisTICAS EXTERNAS DEL DELFiN OSCURO Lagenorhynchus obscurus (GRAY, 1828) DE AGUAS PERUANAS Koen Van Waerebeek Centro Peruano de Estudios Cetol6gicos (CEPEC), Asociaci6n de Ecologfa y Conservaci6n, Casilla 1536, Lima 18, Peru ABSTRACT Individual, sexual and developmental variation is quantified in the external morphology and colouration of the dusky dolphin Lagenorhynchus obscurus from Peruvian coastal waters. No significant difference in body length between sexes is found{p = 0.09) and, generally, little sexual dimorphism is present. However, males have a more anteriorly positioned genital slit and anus and their dorsal fin is more curved, has a broader base and a greater surface area than females Although the dorsal fin apparently serves as a secondary sexual character, the use of it for sexing free-ranging dusky dolphins is discouraged because of high overlap in values Relative growth in 25 body measurements is characterized for both sexes by multiplicative regression equations. The colouration pattern of the dorsal fin, flank patch, thoracic field, flipper stripe and possibly (x2, p = 008) the eye patch, are independent of maturity status. Flipper blaze and lower lip patch are less pigmented in juveniles than in adults No sexual dimorphism is found in the colour pattern The existence of a discrete "Fitzroy" colour form can not be confirmed from available data. Various cases of anomalous, piebald pigmentation are described, probably equivalent to so-called partial albinism Adult dusky dolphins from both SW Africa and New Zealand are 8-10 cm shorter than Peruvian specimens, supporting conclusions of separate populations from a recent skull variability study. -

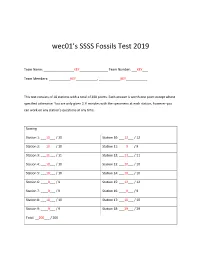

Wec01's SSSS Fossils Test 2019

wec01’s SSSS Fossils Test 2019 Team Name: _________________KEY________________ Team Number: ___KEY___ Team Members: ____________KEY____________, ____________KEY____________ This test consists of 18 stations with a total of 200 points. Each answer is worth one point except where specified otherwise. You are only given 2 ½ minutes with the specimens at each station, however you can work on any station’s questions at any time. Scoring Station 1: ___10___ / 10 Station 10: ___12___ / 12 Station 2: ___10___ / 10 Station 11: ____9___ / 9 Station 3: ___11___ / 11 Station 12: ___11___ / 11 Station 4: ___10___ / 10 Station 13: ___10___ / 10 Station 5: ___10___ / 10 Station 14: ___10___ / 10 Station 6: ____9___ / 9 Station 15: ___12___ / 12 Station 7: ____9___ / 9 Station 16: ____9___ / 9 Station 8: ___10___ / 10 Station 17: ___10___ / 10 Station 9: ____9___ / 9 Station 18: ___29___ / 29 Total: __200___ / 200 Team Number: _KEY_ Station 1: Dinosaurs (10 pt) 1. Identify the genus of specimen A Tyrannosaurus (1 pt) 2. Identify the genus of specimen B Stegosaurus (1 pt) 3. Identify the genus of specimen C Allosaurus (1 pt) 4. Which specimen(s) (A, B, or C) are A, C (1 pt) Saurischians? 5. Which two specimens (A, B, or C) lived at B, C (1 pt) the same time? 6. Identify the genus of specimen D Velociraptor (1 pt) 7. Identify the genus of specimen E Coelophysis (1 pt) 8. Which specimen (D or E) is commonly E (1 pt) found in Ghost Ranch, New Mexico? 9. Which specimen (A, B, C, D, or E) would D (1 pt) specimen F have been found on? 10. -

THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A

s l a m m a y t T i M S N v I i A e G t A n i p E S r a A C a C E H n T M i THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity The Humane Society of the United State s/ World Society for the Protection of Animals 2009 1 1 1 2 0 A M , n o t s o g B r o . 1 a 0 s 2 u - e a t i p s u S w , t e e r t S h t u o S 9 8 THE CASE AGAINST Marine Mammals in Captivity Authors: Naomi A. Rose, E.C.M. Parsons, and Richard Farinato, 4th edition Editors: Naomi A. Rose and Debra Firmani, 4th edition ©2009 The Humane Society of the United States and the World Society for the Protection of Animals. All rights reserved. ©2008 The HSUS. All rights reserved. Printed on recycled paper, acid free and elemental chlorine free, with soy-based ink. Cover: ©iStockphoto.com/Ying Ying Wong Overview n the debate over marine mammals in captivity, the of the natural environment. The truth is that marine mammals have evolved physically and behaviorally to survive these rigors. public display industry maintains that marine mammal For example, nearly every kind of marine mammal, from sea lion Iexhibits serve a valuable conservation function, people to dolphin, travels large distances daily in a search for food. In learn important information from seeing live animals, and captivity, natural feeding and foraging patterns are completely lost. -

SOCIETY of VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY OCTOBER 2015 ABSTRACTS of PAPERS 75Th ANNUAL MEETING

SOCIETY OF VERTEBRATE PALEONTOLOGY OCTOBER 2015 ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS 75th ANNUAL MEETING Hyatt Regency Dallas Dallas, Texas, USA October 14 – 17, 2015 HOST COMMITTEE Stephen Cohen; Anthony R. Fiorillo; Louis Jacobs; Michael Polcyn; Amy Smith; Christopher Strganac; Ronald S. Tykoski; Diana Vineyard; Dale Winkler EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE John Long, President; P. David Polly, Vice President; Catherine A. Forster, Past-President; Glenn Storrs, Secretary; Ted J. Vlamis, Treasurer; Elizabeth Hadly, Member-at-Large; Xiaoming Wang, Member-at-Large; Paul M. Barrett, Member-at-Large SYMPOSIUM CONVENORS Larisa R. G. DeSantis; Anthony R. Fiorillo; Camille Grohé; Marc E. H. Jones; Joshua H. Miller; Christopher Noto; Emma Sherratt; Michael Spaulding; Z. Jack Tseng; Akinobu Watanabe; Lindsay Zanno PROGRAM COMMITTEE David Evans, Co-Chair; Mary Silcox, Co-Chair; Heather Ahrens; Brian Beatty; Jonathan Bloch; Martin Brazeau; Chris Brochu; Richard Butler; Darin Croft; Ted Daeschler; David Fox; Anjali Goswami; Elizabeth Hadly; Pat Holroyd; Marc Jones; Christian Kammerer; Amber MacKenzie; Erin Maxwell; Josh Miller; Jessica Miller-Camp; Kevin Padian; Lauren Sallan; William Sanders; Michelle Stocker; Paul Upchurch; Aaron Wood EDITORS Amber MacKenzie; Erin Maxwell; Jessica Miller-Camp October 2015 PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS 1 Grant Information dinosaur-bearing units in the world. Though exposed in Saskatchewan, outcropping is NSF grant #0847777 (EAR) to D.J. Varrichio sparse, widely distributed, and often difficult to access. Despite this, recently, several microfossil sites have been identified throughout southwestern Saskatchewan, Canada. Technical Session VI (Thursday, October 15, 2015, 9:00 AM) The Saskatchewan sites produce a rich vertebrate record, including chondrichthyans, osteichthyans, turtles, champsosaurs, crocodiles, squamates, amphibians, birds, MULTIDENTICULATE TEETH IN TRIASSIC FISH HEMICALYPTERUS WEIRI mammals, and dinosaurs. -

A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archaeoceti) and Associated Biota from Georgia Author(S): Richard C

A New Middle Eocene Protocetid Whale (Mammalia: Cetacea: Archaeoceti) and Associated Biota from Georgia Author(s): Richard C. Hulbert, Jr., Richard M. Petkewich, Gale A. Bishop, David Bukry and David P. Aleshire Source: Journal of Paleontology , Sep., 1998, Vol. 72, No. 5 (Sep., 1998), pp. 907-927 Published by: Paleontological Society Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1306667 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1306667?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms SEPM Society for Sedimentary Geology and are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Paleontology This content downloaded from 131.204.154.192 on Thu, 08 Apr 2021 18:43:05 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms J. Paleont., 72(5), 1998, pp. 907-927 Copyright ? 1998, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/98/0072-0907$03.00 A NEW MIDDLE EOCENE PROTOCETID WHALE (MAMMALIA: CETACEA: ARCHAEOCETI) AND ASSOCIATED BIOTA FROM GEORGIA RICHARD C. HULBERT, JR.,1 RICHARD M. PETKEWICH,"4 GALE A. -

PDF of Manuscript and Figures

The triple origin of whales DAVID PETERS Independent Researcher 311 Collinsville Avenue, Collinsville, IL 62234, USA [email protected] 314-323-7776 July 13, 2018 RH: PETERS—TRIPLE ORIGIN OF WHALES Keywords: Cetacea, Mysticeti, Odontoceti, Phylogenetic analyis ABSTRACT—Workers presume the traditional whale clade, Cetacea, is monophyletic when they support a hypothesis of relationships for baleen whales (Mysticeti) rooted on stem members of the toothed whale clade (Odontoceti). Here a wider gamut phylogenetic analysis recovers Archaeoceti + Odontoceti far apart from Mysticeti and right whales apart from other mysticetes. The three whale clades had semi-aquatic ancestors with four limbs. The clade Odontoceti arises from a lineage that includes archaeocetids, pakicetids, tenrecs, elephant shrews and anagalids: all predators. The clade Mysticeti arises from a lineage that includes desmostylians, anthracobunids, cambaytheres, hippos and mesonychids: none predators. Right whales are derived from a sister to Desmostylus. Other mysticetes arise from a sister to the RBCM specimen attributed to Behemotops. Basal mysticetes include Caperea (for right whales) and Miocaperea (for all other mysticetes). Cetotheres are not related to aetiocetids. Whales and hippos are not related to artiodactyls. Rather the artiodactyl-type ankle found in basal archaeocetes is also found in the tenrec/odontocete clade. Former mesonychids, Sinonyx and Andrewsarchus, nest close to tenrecs. These are novel observations and hypotheses of mammal interrelationships based on morphology and a wide gamut taxon list that includes relevant taxa that prior studies ignored. Here some taxa are tested together for the first time, so they nest together for the first time. INTRODUCTION Marx and Fordyce (2015) reported the genesis of the baleen whale clade (Mysticeti) extended back to Zygorhiza, Physeter and other toothed whales (Archaeoceti + Odontoceti). -

Mammal Species Native to the USA and Canada for Which the MIL Has an Image (296) 31 July 2021

Mammal species native to the USA and Canada for which the MIL has an image (296) 31 July 2021 ARTIODACTYLA (includes CETACEA) (38) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei - Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 7. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Bos bison - American Bison 2. Oreamnos americanus - Mountain Goat 3. Ovibos moschatus - Muskox 4. Ovis canadensis - Bighorn Sheep 5. Ovis dalli - Thinhorn Sheep CERVIDAE - deer 1. Alces alces - Moose 2. Cervus canadensis - Wapiti (Elk) 3. Odocoileus hemionus - Mule Deer 4. Odocoileus virginianus - White-tailed Deer 5. Rangifer tarandus -Caribou DELPHINIDAE - ocean dolphins 1. Delphinus delphis - Common Dolphin 2. Globicephala macrorhynchus - Short-finned Pilot Whale 3. Grampus griseus - Risso's Dolphin 4. Lagenorhynchus albirostris - White-beaked Dolphin 5. Lissodelphis borealis - Northern Right-whale Dolphin 6. Orcinus orca - Killer Whale 7. Peponocephala electra - Melon-headed Whale 8. Pseudorca crassidens - False Killer Whale 9. Sagmatias obliquidens - Pacific White-sided Dolphin 10. Stenella coeruleoalba - Striped Dolphin 11. Stenella frontalis – Atlantic Spotted Dolphin 12. Steno bredanensis - Rough-toothed Dolphin 13. Tursiops truncatus - Common Bottlenose Dolphin MONODONTIDAE - narwhals, belugas 1. Delphinapterus leucas - Beluga 2. Monodon monoceros - Narwhal PHOCOENIDAE - porpoises 1. Phocoena phocoena - Harbor Porpoise 2. Phocoenoides dalli - Dall’s Porpoise PHYSETERIDAE - sperm whales Physeter macrocephalus – Sperm Whale TAYASSUIDAE - peccaries Dicotyles tajacu - Collared Peccary CARNIVORA (48) CANIDAE - dogs 1. Canis latrans - Coyote 2. -

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA

B.Sc. II YEAR CHORDATA CHORDATA 16SCCZO3 Dr. R. JENNI & Dr. R. DHANAPAL DEPARTMENT OF ZOOLOGY M. R. GOVT. ARTS COLLEGE MANNARGUDI CONTENTS CHORDATA COURSE CODE: 16SCCZO3 Block and Unit title Block I (Primitive chordates) 1 Origin of chordates: Introduction and charterers of chordates. Classification of chordates up to order level. 2 Hemichordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Balanoglossus and its affinities. 3 Urochordata: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Herdmania and its affinities. 4 Cephalochordates: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Branchiostoma (Amphioxus) and its affinities. 5 Cyclostomata (Agnatha) General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Petromyzon and its affinities. Block II (Lower chordates) 6 Fishes: General characters and classification up to order level. Types of scales and fins of fishes, Scoliodon as type study, migration and parental care in fishes. 7 Amphibians: General characters and classification up to order level, Rana tigrina as type study, parental care, neoteny and paedogenesis. 8 Reptilia: General characters and classification up to order level, extinct reptiles. Uromastix as type study. Identification of poisonous and non-poisonous snakes and biting mechanism of snakes. 9 Aves: General characters and classification up to order level. Study of Columba (Pigeon) and Characters of Archaeopteryx. Flight adaptations & bird migration. 10 Mammalia: General characters and classification up