1 Chinese Household Saving and Dependent Children: Theory and Evidence+

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Altruism, Favoritism, and Guilt in the Allocation of Family Resources: Sophie's Choice in Mao's Mass Send Down Movement

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Li, Hongbin; Rosenzweig, Mark Richard; Zhang, Junsen Working Paper Altruism, favoritism, and guilt in the allocation of family resources: Sophie's choice in Mao's mass send down movement Center Discussion Paper, No. 965 Provided in Cooperation with: Economic Growth Center (EGC), Yale University Suggested Citation: Li, Hongbin; Rosenzweig, Mark Richard; Zhang, Junsen (2008) : Altruism, favoritism, and guilt in the allocation of family resources: Sophie's choice in Mao's mass send down movement, Center Discussion Paper, No. 965, Yale University, Economic Growth Center, New Haven, CT This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/27004 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

The Economic Consequences of Demographic Change in East Asia, NBER-EASE Volume 19

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Economic Consequences of Demographic Change in East Asia, NBER-EASE Volume 19 Volume Author/Editor: Takatoshi Ito and Andrew Rose, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-38685-6 ISBN13: 978-0-226-38685-0 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/ito_08-2 Conference Date: June 19-21, 2008 Publication Date: August 2010 Chapter Title: Long-Term Effects of Early-Life Development: Evidence from the 1959 to 1961 China Famine Chapter Authors: Douglas Almond, Lena Edlund, Hongbin Li, Junsen Zhang Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c8166 Chapter pages in book: (321 - 345) 9 Long- Term Effects of Early- Life Development Evidence from the 1959 to 1961 China Famine Douglas Almond, Lena Edlund, Hongbin Li, and Junsen Zhang 9.1 Introduction The dramatic success of China’s One Child Policy in reducing fertility catapults the question of population aging to center stage. As China’s depen- dency ratio increases, the health and productivity of those of working age will play key roles. So far, attention has generally focused on investments in these “working age” cohorts that occur after birth (e.g., educational invest- ments). This chapter focuses instead on the prenatal environment and its impact on health and economic outcomes in adulthood, exploiting the 1959 to 1961 Chinese famine (henceforth, “the Famine”) as a natural experiment in maternal stress and nutrition. While starvation on the scale of the Famine may seem remote, maternal malnutrition is not. -

Online Appendix

The Evolution of China’s One-child Policy and Its Effects on Family Outcomes* Online Appendix Junsen Zhang Junsen Zhang is the Wei Lun Professor of Economics, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong. His email address is [email protected]. 1 I. Empirical Framework The major difficulty in estimating the effect of the one-child policy is that its introduction in 1979 coincided with that of the open-door policy and economic reforms. Following Li and Zhang (2016), my empirical identification is to explore the heterogeneity of the intensity of the one-child policy implementation across provinces/prefectures. Specifically, I construct a measure based on the excess births of each province/prefecture conditional on initial births and other variables. The important variable in my analysis is the excess fertility rate (EFR), which is defined as below: !(����ℎ!" ∙ 1(���!" ≥ 2) ∙ 1(25 ≤ ���!" ≤ 44)) ���! = !(1(���!" ≥ 1) ∙ 1(25 ≤ ���!" ≤ 44)) − !(����ℎ!" ∙ 1(���!" = 1) ∙ 1(25 ≤ ���!" ≤ 44)) where Birth!" is a dummy indicator for woman i, within an age range of 25-44 years old, in prefecture j giving a birth in 1981, and NSC!" is the number of surviving children of women i in prefecture j by the end of 1981. In other words, the EFR in a prefecture here is defined as the percentage of Han mothers (i.e. women with at least one surviving child) aged 25-44 in the 1982 census who gave a higher order birth in 1981. Using the EFR to represent the extent of violation of the one-child policy in prefecture j, I can further examine the effect of the policy on various family outcome variables. -

1 / 5 YI, JUNJIAN Curriculum Vitae November 2010 Gender: Male

YI, JUNJIAN Curriculum Vitae November 2010 Gender: Male Email: [email protected] Birth Year: 1978 Mobile Phone: (852) 9601‐7756 Marital Status: Married Office Phone: (852) 2609‐8228 Citizenship: P. R. China Fax: (852) 2603‐5805 Mail Address: Room 1007, Department of Economics, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong Education Ph.D., Economics, (2007‐2011, expected), The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK); Supervisor: Prof. Junsen Zhang Visiting Ph.D. student (2009‐2010), Department of Economics, University of Chicago; Host supervisor: Prof. James Heckman M.Phil., Economics (2005‐2007), CUHK; Supervisor: Prof. Junsen Zhang Master, Economics (2002‐2005), Zhejiang University; Supervisor: Prof. Xianguo Yao Research Interests Primary fields: Labour and Demographic Economics, Applied Econometrics Secondary fields: Development Economics, Chinese Economy Awards and Scholarships Research Studentship, Department of Economics, CUHK, 2010‐2011 Global Scholarship for Research Excellence of CUHK (CNOOC Grants), 2008‐2009 Best Thesis Award, Department of Economics, CUHK, 2007 (M.Phil. thesis) Postgraduate Studentship, CUHK, 2005‐2010 Teaching and Research Experiences Teaching Assistant, Mathematical Methods in Economics II, Department of Economics, CUHK, 2nd Term 2008/2009 Teaching Assistant, Labour Economics, Department of Economics, CUHK, 1st Term 2008/2009 Teaching Assistant, Introductory Econometrics, Department of Economics, CUHK, 1st Term 2007/2008 Teaching Assistant, Economics on Money and Banking, Department of Economics, CUHK, 1st Term 2005/2006 Research Assistant, Department of Economics, CUHK, Jan. 2006 ‐ Nov. 2010 (for Prof. Junsen Zhang) Research Assistant, School of Economics, Zhejiang University, Mar. 2005 ‐ Jul. 2005 (for Prof. Xianguo Yao) Research Grants 1 / 5 CHUK Special Grant for RGC shortlisted Collaborative Research Fund Application, Hong Kong, 2009‐2011, ʺFamily Background, Educational Inequality, and Preschool Intervention Programs in Hong Kong and the Chinese Mainland: An Analysis with the Experimental Approach,ʺ Co‐I (Prof. -

Peer Migration in China

Peer Migration in China Yuyu Chen Peking University, Guanghua School of Management Ginger Zhe Jin University of Maryland & NBER Yang Yue Xiamen University October 4, 2018 Abstract With 280 million rural laborers migrating to the city in 2017, China is experiencing the largest internal migration in the human history. Using instrumental variables in the 2006 China Agricultural Census, we find that a 10-percentage-point increase in the migration rate of co- villagers raises one's migration probability by 9.18 percent points. Both information exchange at the origin and cost reduction at the destination could explain migration cluster in age, destination, and occupation. However, migration has little effect on the agricultural productivity of non- migrants, probably because labor redundancy is severe at the origin and migrants are more likely of high productivity. Keywords: internal migration, social network, China. JEL: J6, O12, R23. Contact information: Yuyu Chen, Guanghua School of Management, Peking University. Email: [email protected]. Ginger Zhe Jin, Department of Economics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742. Email: [email protected]. Yang Yue, Wang Yanan Institute for Studies in Economics and School of Economics, Xiamen University. Email: [email protected]. This project is a collaborative effort with a local government of China. We would like to thank Hongbin Cai, Wei Li, Brian Viard, Roger Betancourt, Loren Brandt, Judy Hellerstein, John Ham, Matthew Chesnes, Seth Sanders, V. Joseph Hotz, Duncan Thomas, Francisca Antman and Hillel Rapoport for helpful comments. All errors are our own. 1 1. Introduction The past 30 years has witnessed an explosive growth of labor migration inside China. -

Altruism, Favoritism, and Guilt in the Allocation of Family Resources: Sophie’S Choice in Mao’S Mass Send Down Movement

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Discussion Papers Economic Growth Center 9-1-2008 Altruism, Favoritism, and Guilt in the Allocation of Family Resources: Sophie’s Choice in Mao’s Mass Send Down Movement Hongbin Li Mark Rosenzweig Junsen Zhang Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/egcenter-discussion-paper-series Recommended Citation Li, Hongbin; Rosenzweig, Mark; and Zhang, Junsen, "Altruism, Favoritism, and Guilt in the Allocation of Family Resources: Sophie’s Choice in Mao’s Mass Send Down Movement" (2008). Discussion Papers. 973. https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/egcenter-discussion-paper-series/973 This Discussion Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Economic Growth Center at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Discussion Papers by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECONOMIC GROWTH CENTER YALE UNIVERSITY P.O. Box 208629 New Haven, CT 06520-8269 http://www.econ.yale.edu/~egcenter/ CENTER DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 965 Altruism, Favoritism, and Guilt in the Allocation of Family Resources: Sophie’s Choice in Mao’s Mass Send Down Movement Hongbin Li Tsinghua University Mark Rosenzweig Yale University Junsen Zhang The Chinese University of Hong Kong September 2008 Notes: Center discussion papers are preliminary materials circulated to stimulate discussion and critical comments. The work described in this paper was substantially supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Project no. -

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES PEER MIGRATION in CHINA Yuyu Chen Ginger Zhe Jin

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES PEER MIGRATION IN CHINA Yuyu Chen Ginger Zhe Jin Yang Yue Working Paper 15671 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15671 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2010 This project is a collaborative effort with a local government of China. We would like to thank Hongbin Cai, Wei Li, Brian Viard, Roger Betancourt, Loren Brandt, Judy Hellerstein, John Ham, Matthew Chesnes, Seth Sanders, V. Joseph Hotz, Duncan Thomas, Francisca Antman and Hillel Rapoport for helpful comments. All errors are our own. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by Yuyu Chen, Ginger Zhe Jin, and Yang Yue. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. Peer Migration in China Yuyu Chen, Ginger Zhe Jin, and Yang Yue NBER Working Paper No. 15671 January 2010, Revised September 2010 JEL No. J6,O12,R23 ABSTRACT We aim to quantify the role of social networks in job-related migration. With over 130 million rural labors migrating to the city each year, China is experiencing the largest internal migration in the human history. Using instrumental variables in the 2006 China Agricultural Census, we find that a 10-percentage-point increase in the migration rate of co-villagers raises one's migration probability by 7.27 percent points, an effect comparable to an increase of education by 7-8 years. -

Fertility, Household Structure, and Parental Labor Supply: Evidence from Rural China

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Li, Hongbin; Yi, Junjian; Zhang, Junsen Working Paper Fertility, Household Structure, and Parental Labor Supply: Evidence from Rural China IZA Discussion Papers, No. 9342 Provided in Cooperation with: IZA – Institute of Labor Economics Suggested Citation: Li, Hongbin; Yi, Junjian; Zhang, Junsen (2015) : Fertility, Household Structure, and Parental Labor Supply: Evidence from Rural China, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 9342, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/120992 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der -

Economic Growth, Comparative Advantage, and Gender Differences

Economic Growth, Comparative Advantage, and Gender Differences in Schooling Outcomes: Evidence from the Birthweight Differences of Chinese Twins Using data from two surveys on twins in the People’s Republic of China, the paper estimates the gender-specific effects of birthweight on a variety of schooling and labor market outcomes. Applying a simple model of schooling and occupational choice incorporating biological differences in brawn between males and females, it shows that the comparative advantage of females in skill is reflected in their greater investment in education and in the selection of more skill-intensive occupations relative to males. ADB Economics Working Paper Series About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.7 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 828 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Economic Growth, Comparative Advantage, and Gender Differences in Schooling Outcomes: Evidence from the Birthweight Differences of Chinese Twins Mark R. Rosenzweig and Junsen Zhang No. 323 | December 2012 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org/economics Printed on recycled paper Printed in the Philippines ADB Economics Working Paper Series Economic Growth, Comparative Advantage, and Gender Differences in Schooling Outcomes: Evidence from the Birthweight Differences of Chinese Twins Mark R. -

Date Time Session Number Session Title Presenter (Last Name

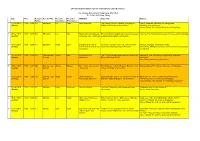

2019 International Symposium on Contemporary Labor Economics The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shenzhen 15 - 16 Dec 2019 (Sun - Mon) Date Time Session Session Title Presenter Presenter Affiliation Paper Title Authors Number (Last Name) (First Name) 1 15 Dec 2019 13:30 - 15:00 1-A Education Hu Yuan Jinan University The Causal Effects of Parents' Schooling on Jere R. Behrman, University of Pennsylvania; (Sunday) Children's Schooling in Urban China Yuan Hu, Jinan University*; Junsen Zhang, The Chinese University of Hong Kong 2 15 Dec 2019 13:30 - 15:00 1-A Education Luo Wei The Hong Kong University Economic Reform and Human Capital Investment: Wei Luo, The Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (Sunday) of Science and Technology Evidence from China's Land Reform 3 15 Dec 2019 13:30 - 15:00 1-A Education Wang Danli Shanghai University of (From) the Kungfu's Curse: The Effect of Clan Ming Lu, Shanghai Jiaotong University; (Sunday) International Business and Conflicts on Education and Its Evolution Danli Wang, Shanghai University of International Business and Economics Economics* 4 15 Dec 2019 13:30 - 15:00 1-B Eldercare and Zhang Anqi The University of The Effect of Introducing a Universal Pension on Katsushi S. Imai, University of Manchester, and Kobe (Sunday) pension Manchester Elderly Poverty in China University; Anqi Zhang, University of Manchester* 5 15 Dec 2019 13:30 - 15:00 1-B Eldercare and Zhang Shujuan The Chinese University of Family Support or Social Support: Evidence from Shujuan Zhang, The Chinese University of Hong -

Capitalizing China

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Capitalizing China Volume Author/Editor: Joseph P. H. Fan and Randall Morck, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-23724-9; 978-0-226-23724-4 (cloth) Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/morc10-1 Conference Date: December 15-16, 2009 Publication Date: November 2012 Chapter Title: Why Are Saving Rates So High in China? Chapter Author(s): Dennis Tao Yang, Junsen Zhang, Shaojie Zhou Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c12068 Chapter pages in book: (p. 249 - 278) 5 Why Are Saving Rates So High in China? Dennis Tao Yang, Junsen Zhang, and Shaojie Zhou 5.1 Introduction The spectacular economic growth of China in the past three decades has been associated with an equally remarkable high rate of saving. While the gross national saving as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) hovered just a little above 35 percent in the 1980s, the average yearly rate climbed to 41 percent in the 1990s (fi gure 5.1). Since China’s entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO), the growth in aggregate saving acceler- ated, surging from just below 38 percent in 2000 to an unprecedented 53 per- cent in 2007. China’s national saving rates since 2000 have been one of the highest worldwide, far surpassing the rates prevailing in Japan, South Korea, and other East Asian economies during the years of their miracle growth.1 Dennis Tao Yang is professor of business administration at the University of Virginia. -

ZHANG Junsen Personal Data Address: Department of Economics

CURRICULUM VITAE (May 2009) ZHANG Junsen Personal Data Address: Department of Economics Chinese University of Hong Kong Shatin, NT, Hong Kong Phone: 852-2609-8186 Fax: 852-2603-5805 (Economics Department) E-mail: [email protected] Marital Status: Married with two children Research Areas Labour and Demographic Economics; Applied Econometrics; Chinese Economy Education 1990 Ph.D. (Economics), McMaster University, Ontario, Canada 1986 M.A. (Economics), McMaster University, Ontario, Canada 1985 M.B.A. programme (except thesis), Department of Management Science, Nankai University, Tianjin, China 1983 B.Sc. (Engineering), Zhejiang University, Zhejiang, China Employment 2004.10 Professor of Economics (Chair Professor), Department of Economics, Chinese University of Hong Kong (C.U.H.K.) 2000 -- 2004 Professor, Department of Economics, C.U.H.K. 1995 -- 2000 Associate Professor, Department of Economics, C.U.H.K. 1999 -- Present Research Fellow, The Institute for the Study of Labour, Bonn, Germany 1993 -- 1995 Assistant Professor (Lecturer), Department of Economics, C.U.H.K. 1990 -- 1993 Assistant Professor, Department of Economics, The University of Western Ontario (U.W.O.), Canada 1989 -- 1990 Lecturer in Econometrics, Department of Statistics, Faculty of Economics and Commerce, the Australian National University (A.N.U.) Major Administrative Duties Head of the Graduate Division (Economics), 1998- Associate Dean (Research), Faculty of Social Science, 2004.11- Acting Chairman of Department of Economics, various times Teaching Evaluation Coordinator,