Close Air Support: Aviators' Entrée Into the Band of Brothers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JP 3-09.3, Close Air Support, As a Basis for Conducting CAS

Joint Publication 3-09.3 Close Air Support 08 July 2009 PREFACE 1. Scope This publication provides joint doctrine for planning and executing close air support. 2. Purpose This publication has been prepared under the direction of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. It sets forth joint doctrine to govern the activities and performance of the Armed Forces of the United States in joint operations and provides the doctrinal basis for interagency coordination and for US military involvement in multinational operations. It provides military guidance for the exercise of authority by combatant commanders and other joint force commanders (JFCs) and prescribes joint doctrine for operations, education, and training. It provides military guidance for use by the Armed Forces in preparing their appropriate plans. It is not the intent of this publication to restrict the authority of the JFC from organizing the force and executing the mission in a manner the JFC deems most appropriate to ensure unity of effort in the accomplishment of the overall objective. 3. Application a. Joint doctrine established in this publication applies to the Joint Staff, commanders of combatant commands, subunified commands, joint task forces, and subordinate components of these commands, and the Services. b. The guidance in this publication is authoritative; as such, this doctrine will be followed except when, in the judgment of the commander, exceptional circumstances dictate otherwise. If conflicts arise between the contents of this publication and the contents of Service publications, this publication will take precedence unless the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, normally in coordination with the other members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has provided more current and specific guidance. -

The Art of Strafing

The Art of Strafing By Richard B.H. Lewis ODERN fighter pilots risk their lives Mevery day performing the act of strafing, which to some may seem like a tactic from a bygone era. Last Novem- ber, an F-16 pilot, Maj. Troy L. Gilbert, died strafing the enemy in Iraq, trying Painting by Robert Bailey to protect coalition forces taking fire on the ground. My first thought was, “Why was an F-16 doing that mission?” But I already knew the answer. In the 1980s, at the height of the Cold War, I was combat-ready in the 512th Fighter Squadron, an F-16 unit at Ramstein AB, Germany. We had to maintain combat status in air-to- air, air-to-ground, and nuclear strike operations. We practiced strafing oc- casionally. We were not very good at it, but it was extremely challenging. There is a big difference between was “Gott strafe England” (“God punish flight controls and a 30 mm Gatling flying at 25,000 feet where you have England”). The term caught on. gun. I have seen the aircraft return from plenty of room to maneuver and you In the World War I Battle of St. Mihiel, combat with one engine and major parts can barely see a target, and at 200 feet, Capt. Eddie Rickenbacker once strafed of a wing and flight controls blown off. where the ground is rushing right below eight German artillery pieces, each Unquestionably, the A-10 is the ultimate you and you can read the billboards drawn by a team of six horses. -

Air-To-Ground Battle for Italy

Air-to-Ground Battle for Italy MICHAEL C. MCCARTHY Brigadier General, USAF, Retired Air University Press Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama August 2004 Air University Library Cataloging Data McCarthy, Michael C. Air-to-ground battle for Italy / Michael C. McCarthy. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-58566-128-7 1. World War, 1939–1945 — Aerial operations, American. 2. World War, 1939– 1945 — Campaigns — Italy. 3. United States — Army Air Forces — Fighter Group, 57th. I. Title. 940.544973—dc22 Disclaimer Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Air University, the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or any other US government agency. Cleared for public release: distribution unlimited. Air University Press 131 West Shumacher Avenue Maxwell AFB AL 36112–6615 http://aupress.maxwell.af.mil ii Contents Chapter Page DISCLAIMER . ii FOREWORD . v ABOUT THE AUTHOR . vii PREFACE . ix INTRODUCTION . xi Notes . xiv 1 GREAT ADVENTURE BEGINS . 1 2 THREE MUSKETEERS TIMES TWO . 11 3 AIR-TO-GROUND BATTLE FOR ITALY . 45 4 OPERATION STRANGLE . 65 INDEX . 97 Photographs follow page 28 iii THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Foreword The events in this story are based on the memory of the author, backed up by official personnel records. All survivors are now well into their eighties. Those involved in reconstructing the period, the emotional rollercoaster that was part of every day and each combat mission, ask for understanding and tolerance for fallible memories. Bruce Abercrombie, our dedicated photo guy, took most of the pictures. -

Repüléstudományi Közlemények (ISSN: 1417-0604) 2002., Pp

Varga Mihály mk. alezredes ZMNE KLHTK Dékáni Titkárság [email protected] Doctrine, organization and weapon systems of close air support of the Luftwaffe in World War II A Lufwaffe közvetlen légi támogatási doktrínája, szervezete és fegyver-rendszerei a második világháborúban Resume The author presents the essence of doctrine, organization, command and control and weapon systems of close air support of Luftwaffe in World War II. He gives an overview about most frequently used aircraft and their tactical-technical features. The article demonstrates that the close air support is one of the most important components of the tactics success and it was since the appearance of the aerial warfare. Rezümé A szerző ismerteti a lényegét a második világháborús Luftwaffe közvetlen légi támogatási doktrínájának, a végrehajtásért felelős szervezetnek és a légi vezetési és irányítási rendszernek. A szerző áttekinti a leggyakrabban alkalmazott fegyver- rendszereket, csata és bombázó repülőgépeket, valamint azok jellemzőit. A cikk demonstrálja, hogy a harcászati siker egyik legfontosabb összetevőjének tekinthetjük a csapatok közvetlen légi támogatását a légi hadviselés kezdetei óta. Introduction The close air support (generally supporting the land forces from air with fire) one of the most important components of the tactics success and it was since the appearance of the aerial warfare. According to the definition of close air support (CAS): „air action against hostile targets which are in close proximity to friendly forces and which require detailed integration of each air mission with the fire and movement of those forces” 1 At the beginning of the world war II, only the Luftwaffe had made a theory of deployment and a tactical-technical procedures for direct fire support for ground forces. -

HELP from ABOVE Air Force Close Air

HELP FROM ABOVE Air Force Close Air Support of the Army 1946–1973 John Schlight AIR FORCE HISTORY AND MUSEUMS PROGRAM Washington, D. C. 2003 i Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Schlight, John. Help from above : Air Force close air support of the Army 1946-1973 / John Schlight. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Close air support--History--20th century. 2. United States. Air Force--History--20th century. 3. United States. Army--Aviation--History--20th century. I. Title. UG703.S35 2003 358.4'142--dc22 2003020365 ii Foreword The issue of close air support by the United States Air Force in sup- port of, primarily, the United States Army has been fractious for years. Air commanders have clashed continually with ground leaders over the proper use of aircraft in the support of ground operations. This is perhaps not surprising given the very different outlooks of the two services on what constitutes prop- er air support. Often this has turned into a competition between the two serv- ices for resources to execute and control close air support operations. Although such differences extend well back to the initial use of the airplane as a military weapon, in this book the author looks at the period 1946- 1973, a period in which technological advances in the form of jet aircraft, weapons, communications, and other electronic equipment played significant roles. Doctrine, too, evolved and this very important subject is discussed in detail. Close air support remains a critical mission today and the lessons of yesterday should not be ignored. This book makes a notable contribution in seeing that it is not ignored. -

Immersive Forward Air Controller Training: Your Complete Call-For-Fire

TM Your complete call-for-fire and close air support solution Immersive forward air controller training: VBS3Fires FST is an immersive Call-For-Fire and Close Air Support training simulation like no other. It combines the flexibility and stunning visuals of VBS3 with a highly sophisticated close air support simulation system, highly realistic FO and JTAC workflow, as well as all of the functionality available in VBS3Fires. The Close Air Support engine supports the semi- autonomous control of aircraft. No qualified pilot is required to operate a VBS3Fires FST training scenario. Instead, a sophisticated artificial intelligence engine pilots aircraft. This frees the instructor from concentrating on flying an aircraft and allows them to focus on training. Use Cases: Instructor-led JTAC training for Type 1, 2 and 3 control Instructor-led call-for-fire Training for ground based artillery, mortars and NGF Desktop training for CFF and basic CAS Joint Fires training for coordinating air and ground based fires Fire Planning Airspace Deconfliction teaching and visualisation Indirect fire with AC-130 gunship VBS3Fires FST Features: Elevating close air support to a new level VBS3Fires FST allows FACs or JTACs to move freely through the virtual environment. They can interact with manoeuvre elements, engage or be engaged by the enemy, relocate during a scenario and interact with vehicles. The system has a structured workflow developed with SMEs to ensure that there is a smooth and natural progression through the phases of allocating aircraft on station, check in procedures, game plans, nine-line/ five line briefs, talk-on, instructions during an attack, and bomb hit assessments. -

The Last of the Dive-Bombers by Walter J

The Army Air Forces turned to dive-bombers for accuracy, but the A-24 Banshee found itself in the wrong places at the wrong times. The Last of the Dive-bombers By Walter J. Boyne n warfare, as in business, timing and location are everything. The classic Douglas dive-bomber of IWorld War II served the Navy brilliantly as the SBD Dauntless, while the virtu- ally identical A-24 Banshee had only a mediocre career with the US Army Air Forces. There were many reasons for this, but the main one was the combination of the Navy’s long-standing training in dive-bombing and the nature of its tar- gets, which allowed the SBD to perform. In contrast, dive-bombing was thrust upon the heavy-bomber-centric AAF following the spectacular successes of the German Junkers Ju 87 Stuka in 70 AIR FORCE Magazine / December 2010 the initial phases of World War II. The 1926, and instructed his squadron in Left top: An A-24 on the ramp on undeniably menacing look of the Ju 87 the technique. Makin, in the Gilbert Island chain. Left certainly made the pitch easier as well. He made Navy history on Oct. 22, bottom: German Stukas in 1943. Above: An RA-24B assigned to Air Transport When at last the AAF sought to obtain 1926, with a surprise dive-bombing Command. a dive-bombing capability, it took deliv- mock attack on ships of the Pacific ery of Douglas A-24s (erstwhile Navy Fleet, using the Curtiss F6C-2 single- During the 1910-20 Mexican Civil SBD-3s) in mid-1941. -

The Fighting Five-Tenth: One Fighter-Bomber Squadron's

The Fighting Five-Tenth: One Fighter-Bomber Squadron’s Experience during the Development of World War II Tactical Air Power by Adrianne Lee Hodgin Bruce A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 14, 2013 Keywords: World War II, fighter squadrons, tactical air power, P-47 Thunderbolt, European Theater of Operations Copyright 2013 by Adrianne Lee Hodgin Bruce Approved by William Trimble, Chair, Alumni Professor of History Alan Meyer, Assistant Professor of History Mark Sheftall, Associate Professor of History Abstract During the years between World War I and World War II, many within the Army Air Corps (AAC) aggressively sought an independent air arm and believed that strategic bombardment represented an opportunity to inflict severe and dramatic damages on the enemy while operating autonomously. In contrast, working in cooperation with ground forces, as tactical forces later did, was viewed as a subordinate role to the army‘s infantry and therefore upheld notions that the AAC was little more than an alternate means of delivering artillery. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for a significantly expanded air arsenal and war plan in 1939, AAC strategists saw an opportunity to make an impression. Eager to exert their sovereignty, and sold on the efficacy of heavy bombers, AAC leaders answered the president‘s call with a strategic air doctrine and war plans built around the use of heavy bombers. The AAC, renamed the Army Air Forces (AAF) in 1941, eventually put the tactical squadrons into play in Europe, and thus tactical leaders spent 1943 and the beginning of 1944 preparing tactical air units for three missions: achieving and maintaining air superiority, isolating the battlefield, and providing air support for ground forces. -

Conventional Weapons

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 45 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2009 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Windrush Group Windrush House Avenue Two Station Lane Witney OX28 4XW 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary Group Captain K J Dearman FRAeS Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA Members Air Commodore G R Pitchfork MBE BA FRAes *J S Cox Esq BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain A J Byford MA MA RAF *Wing Commander P K Kendall BSc ARCS MA RAF Wing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Manager *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS RFC BOMBS & BOMBING 1912-1918 by AVM Peter Dye 8 THE DEVELOPMENT OF RAF BOMBS, 1919-1939 by 15 Stuart Hadaway RAF BOMBS AND BOMBING 1939-1945 by Nina Burls 25 THE DEVELOPMENT OF RAF GUNS AND 37 AMMUNITION FROM WORLD WAR 1 TO THE -

Beyond Close Air Support Forging a New Air-Ground Partnership

CHILD POLICY This PDF document was made available CIVIL JUSTICE from www.rand.org as a public service of EDUCATION the RAND Corporation. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE Jump down to document6 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit POPULATION AND AGING research organization providing PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY objective analysis and effective SUBSTANCE ABUSE solutions that address the challenges TERRORISM AND facing the public and private sectors HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND around the world. INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND Project AIR FORCE View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Beyond Close Air Support Forging a New Air-Ground Partnership Bruce R. Pirnie, Alan Vick, Adam Grissom, Karl P. Mueller, David T. Orletsky Prepared for the United States Air Force Approved for public release; distribution unlimited The research described in this report was sponsored by the United States Air Force under Contract F49642-01-C-0003. -

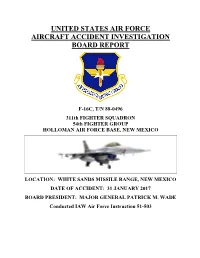

F-16C, T/N 88-0496

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION BOARD REPORT F-16C, T/N 88-0496 311th FIGHTER SQUADRON 54th FIGHTER GROUP HOLLOMAN AIR FORCE BASE, NEW MEXICO LOCATION: WHITE SANDS MISSILE RANGE, NEW MEXICO DATE OF ACCIDENT: 31 JANUARY 2017 BOARD PRESIDENT: MAJOR GENERAL PATRICK M. WADE Conducted IAW Air Force Instruction 51-503 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY UNITED STATES AIR FORCE AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION F-16C, T/N 88-0496 WHITE SANDS MISSILE RANGE, NEW MEXICO 31 JANUARY 2017 On 31 January 2017, at 19:18:31 hours local (L), an F-16C, Tail Number (T/N) 88-0496, fired 155 20mm training projectile bullets on the supporting Joint Terminal Attack Controllers’ (JTAC) position at the Red Rio bombing range (located on the White Sands Missile Range), injuring one military member and killing a civilian contractor. The mishap pilot (MP) and mishap instructor pilot (MIP) were assigned to the 311th fighter squadron, Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico (NM). The MP was enrolled in the F-16 Formal Training Unit program, flying a night, close-air support (CAS) training sortie under the MIP’s supervision. After a successful bomb pass and two failed strafing attempts, the MP errantly pointed his aircraft at the observation point and fired his gun. One 20mm TP bullet fragment struck the mishap contractor (MC) in the back of the head. A UH-60 aircrew extracted the MC, provided urgent care, and transported him to Alamogordo, NM. The MC died at the hospital at 21:01 hours L. The MP was a USAF First Lieutenant, with 86 total flying hours, 60.9 in the F-16. -

Night Air Combat

AU/ACSC/0604G/97-03 NIGHT AIR COMBAT A UNITED STATES MILITARY-TECHNICAL REVOLUTION A Research Paper Presented To The Research Department Air Command and Staff College In Partial Fulfillment of the Graduation Requirements of ACSC By Maj. Merrick E. Krause March 1997 Disclaimer The views expressed in this academic research paper are those of the author(s) and do not reflect the official policy or position of the US government or the Department of Defense. ii Contents Page DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................ ii LIST OF TABLES......................................................................................................... iv PREFACE....................................................................................................................... v ABSTRACT................................................................................................................... vi A UNITED STATES MILITARY-TECHNICAL REVOLUTION.................................. 1 MILITARY-TECHNICAL REVOLUTION THEORY ................................................... 5 Four Elements of an MTR........................................................................................... 9 The Revolution in Military Affairs............................................................................. 12 Revolution or Evolution? .......................................................................................... 15 Strength, Weakness, and Relevance of the MTR Concept ........................................