State Legislative Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Operators for PDF, Common to All Language Levels

STATE LEGISLATIVE BRANCH 2004 Legislative Elections By Tim Storey Before launching into the analysis of the 2004 state legislative elections, it is instructive to go back two years to the last major legislative elections. The year 2002 was a banner year for the Republican Party in legislatures; they seized eight legislative chambers and claimed bragging rights by taking the majority of legislative seats nationwide for the first time in 50 years. When it comes to state legislatures, Democrats Control of Legislative Seats bounced back big in 2004 despite their defeat at the Perhaps the parity in state legislatures is best top of the ticket where George Bush extended his understood by looking at the total number of seats stay in the White House by defeating John Kerry by held by each party. There are 7,382 total legislative a relatively close 35 electoral vote margin. The seats in the 50 states. Of those, 7,316 are held by Democrats took control of seven legislative cham- partisans from the two major political parties. Third bers and had a quasi-victory by gaining ties in both party legislators hold 16 seats, and Nebraska voters the Iowa Senate and Montana House—both con- choose the 49 senators there in a non-partisan trolled by the GOP before the election. The Demo- election. As of mid-January 2005, the difference crats also regained the title of holding the most seats between the two major parties was a miniscule one although their margin is a tiny fraction of 1 percent— seat, with the advantage going to the Democrats. -

Prayer Practices

Floor Action 5-145 Prayer Practices Legislatures operate with a certain element of pomp, ceremony and procedure that flavor the institution with a unique air of tradition and theatre. The mystique of the opening ceremonies and rituals help to bring order and dignity to the proceedings. One of these opening ceremonies is the offering of a prayer. Use of legislative prayer. The practice of opening legislative sessions with prayer is long- standing. The custom draws its roots from both houses of the British Parliament, which, according to noted parliamentarian Luther Cushing, from time ”immemorial” began each day with a “reading of the prayers.” In the United States, this custom has continued without interruption at the federal level since the first Congress under the Constitution (1789) and for more than a century in many states. Almost all state legislatures still use an opening prayer as part of their tradition and procedure (see table 02-5.50). In the Massachusetts Senate, a prayer is offered at the beginning of floor sessions for special occasions. Although the use of an opening prayer is standard practice, the timing of when the prayer occurs varies (see table 02-5.51). In the majority of legislative bodies, the prayer is offered after the floor session is called to order, but before the opening roll call is taken. Prayers sometimes are given before floor sessions are officially called to order; this is true in the Colorado House, Nebraska Senate and Ohio House. Many chambers vary on who delivers the prayer. Forty-seven chambers allow people other than the designated legislative chaplain or a visiting chaplain to offer the opening prayer (see table 02-5.52). -

Grassley up 9 Points in Iowa Senate Race, Quinnipiac University Swing State Poll Finds; Bennet Swamping Gop Challenger in Colorado

Peter A. Brown, Assistant Director (203) 535-6203 Tim Malloy, Assistant Director (203) 645-8043 Rubenstein Pat Smith (212) 843-8026 FOR RELEASE: AUGUST 18, 2016 GRASSLEY UP 9 POINTS IN IOWA SENATE RACE, QUINNIPIAC UNIVERSITY SWING STATE POLL FINDS; BENNET SWAMPING GOP CHALLENGER IN COLORADO Incumbent U.S. Senators hold comfortable likely voter leads in reelection races in Colorado and Iowa, according to a Quinnipiac University Swing State Poll released today. In Colorado, first-term Democratic Sen. Michael Bennet is cruising to a second term with a 54 – 38 percent lead over El Paso County Commissioner Darryl Glenn, his Republican challenger, the independent Quinnipiac (KWIN-uh-pe-ack) University Poll finds. Party loyalty trumps race as non-white likely voters go Democratic 64 – 22 percent, even though Glenn is black. White voters back the incumbent 53 – 41 percent. Bennet leads 96 – 1 percent among Democrats and 55 – 33 percent among independent voters. Republicans back Glenn 84 – 8 percent. Bennet leads 59 – 33 percent among women and 49 – 43 percent among men. “For first term Sen. Michael Bennet, the path to a second six years in DC may seem as clear as a crisp day in the Rockies, but there is still time for Darryl Glenn to summon enough support to win a Senate seat the GOP sorely needs,” said Tim Malloy, assistant director of the Quinnipiac University Poll. Iowa In Iowa, six-term Republican incumbent Sen. Chuck Grassley is holding off his Democratic challenger, former Lieutenant Gov. Patty Judge 51 – 42 percent. The challenger gets no bounce from women likely voters, who are divided, with 47 percent for the Democrat and 46 percent for the Republican. -

Electronic Voting

Short Report: Electronic Voting 15 SR 001 Date: April 13, 2015 by: Matthew Sackett, Research Manager TABLE OF CONTENTS Part I: Introduction Part II: General Overview of Electronic Voting Systems Part III: Summary of National Conference of State Legislatures Research on Electronic Voting (Survey) Part IV: Wyoming Legislature’s process and procedures relating to vote taking and recording Part V: Conclusion Attachments: Attachment A: NCSL Survey Results WYOMING LEGISLATIVE SERVICE OFFICE • 213 State Capitol • Cheyenne, Wyoming 82002 TELEPHONE (307) 777-7881 • FAX (307) 777-5466 • EMAIL • [email protected] • WEBSITE http://legisweb.state.wy.us Page 2 PART I: INTRODUCTION As part of the Capitol renovation process, the Select Committee on Legislative Technology asked LSO staff to prepare an update to a report that was done for them previously (2008) about electronic voting systems. The previous report included as its main focus a survey conducted by the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) to other states that asked a variety of questions on electronic voting both in terms of equipment and legislative procedures. For purposes of this update, LSO again reached out to Ms. Brenda Erickson, a staff specialist knowledgeable in the areas of electronic voting and voting process and procedure from NCSL, to again conduct a survey related to process and procedure of other states related to electronic voting. Before engaging in a discussion of electronic voting systems, it is important to recognize that electronic voting systems are tools for facilitating legislative business. These systems are subject to legislative rules, processes and procedures. It is the implementation, and subsequent enforcement, of legislative rules and procedures related to voting process, not just the systems technology, which create accountability in the process. -

Some Do's and Don'ts During Your Visit

Advocate’s Guide to Visiting the Iowa Capitol To learn more about advocacy at the state capitol, contact Sheila Hansen at [email protected] or visit www.commongoodiowa.org. Thank you so much for coming to Des Moines to meet with your legislators! You are about to participate in one of the most important and effective strategies to influence the legislative process and help ensure future public support for programs and services for young children. Furthermore, you can take pride in knowing that your visit to your legislative delegation contributes to our great democratic process and sets an example for others to follow. The purpose of your visit is to educate legislators about the importance of the issues you care about — and how their support can advance opportunity for Iowans. What is Your Legislator’s Job? Your Iowa legislators do more than just vote “aye” or “nay” on bills. They are responsible for: Lawmaking • Studying, discussing and voting on proposed legislation • Allocating money to state agencies and programs • Creating, modifying and abolishing state laws and programs as necessary • Settling conflicts, righting injustices and making authoritative decisions Representing • Serving constituents living in the district • Doing what is in the best interest of the state as a whole • Acting as a liaison between citizens and state government Monitoring • Overseeing the work of departments and agencies funded by the Legislature • Ensuring that laws are being carried out according to legislative intent • Confirming the Governor’s appointments and responding to vetoes • Keeping the lawmaking process open and honest The information you share with them will help them effectively fulfil their responsibilities. -

Cortevapac Q4 2019

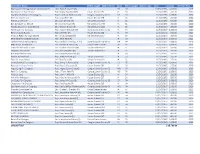

Committee Name Candidate Office Sought - District Name State Office Sought - District Type Date Amount Election Year Ryan Quarles for Agriculture Commissioner Hon. Ryan F. Quarles (R) KY CB 10/15/2019 $ 2,000.00 2019 Kaufmann for State House Rep. Bobby Kaufmann (R) House District 073 IA SH 11/5/2019 $ 250.00 2020 Lisa Blunt Rochester For Congress Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester (D) Congressional District 01 DE FH 11/5/2019 $ 2,500.00 2020 Klein for Statehouse Rep. Jarad Klein (R) House District 078 IA SH 11/5/2019 $ 250.00 2020 Friends of Whitver Sen. Jack Whitver (R) Senate District 019 IA SS 11/5/2019 $ 500.00 2020 Dan Zumbach for Senate Sen. Dan Zumbach (R) Senate District 048 IA SS 11/5/2019 $ 250.00 2020 Waylon Brown for State Senate Sen. Waylon Brown (R) Senate District 026 IA SS 11/5/2019 $ 250.00 2020 Finkenauer For Congress Rep. Abby Finkenauer (D) Congressional District 01 IA FH 11/5/2019 $ 2,500.00 2020 Hein for State House Rep. Lee Hein (R) House District 096 IA SH 11/5/2019 $ 500.00 2020 Amanda Ragan for Iowa Senate Sen. Amanda Ragan (D) Senate District 027 IA SS 11/5/2019 $ 250.00 2022 Mike Naig for Iowa Agriculture Hon. Mike Naig (R) IA CB 11/5/2019 $ 1,000.00 2022 Sanford Bishop For Congress Rep. Sanford D. Bishop, Jr. (D) Congressional District 02 GA FH 11/5/2019 $ 1,000.00 2020 Mike Braun For Indiana Sen. Michael K. Braun (R) United States Senate IN FS 11/5/2019 $ 1,000.00 2024 Schneider for State Senate Sen. -

Leadership Staffing Support

SO=Session Only FT=Full Time PERSONAL STAFF - a study of western states PT=Part Time STATE PERSONAL STAFF OFFICER MAJORITY MINORITY Comments TERM SESSION LIMITS Alaska House 1-2 FT per member 4-FT 4-FT 3-FT None Annual 40 Members Alaska Senate 2-3 FT per member 4-FT 4-FT 3-FT None Annual 20 Members Arizona House 1-FT per 2 members 2-FT 1-FT 1-FT Yes Annual 60 Members Arizona Senate 1-FT per 2 members 2-FT 1-FT 1-FT Yes Annual 30 Members Arkansas House Constituent Services No Additional No Additional No Additional Chief Clerk hires staff Yes Annual 100 Members 4-6 FT Arkansas Senate Constituent Services No Additional No Additional No Additional Chief Clerk hires staff 35 Members 4 FT Colorado House 2-SO per member 1-FT 4-FT 4-FT Hours may be used in the Yes Annual 65 Members not to exceed 690 hrs 4-SO 3-SO interim per fiscal year Colorado Senate 1-SO per member 8-FT Shares Presiding 5-FT 50 hrs in interim Yes Annual 35 Members not to exceed 420 hrs 2-SO Officer Staff 2-SO $10.50 per hour per fiscal year Hawaii House 1-FT per member 4-FT 2-FT 2-FT Similar to Hawaii Senate None Annual 51 Members 2-FT Pro Tem (see below) Hawaii Senate 2-FT per member 5-FT V.P. 3-FT No Additional Monthly allocation for None Annual 25 Members (1 serves as 1-SO additional SO staff ($5,000 committee clerk) with an extra $1-2,000 if chairman or leader) Idaho House 1-SO per chairman 1-SO 1-SO 3-SO Leadership hires staff None Annual 70 Members 1-PT in Interim STATE PERSONAL STAFF OFFICER MAJORITY MINORITY Comments TERM SESSION Idaho Senate 1-SO per chairman & 3-FT -

Election Laws (2020)

Election Law Volume (2020) ELECTION LAWS OF IOWA 2020 Published under the authority of Iowa Code chapter 2B by the Legislative Services Agency GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF IOWA Des Moines EDITOR’S NOTE This publication contains all election laws to be included in the 2021 Iowa Code. Changes in Code language to be included in the 2021 Code are marked by highlighting in yellow. Code sections with changes are also highlighted in yellow in the Table of Contents. Some changes in Code sections highlighted in yellow will not take effect until January 1, 2021, and are identified by an asterisk in the Code section text and an accompanying footnote which states: *SEE CODE 2020 FOR LAW IN EFFECT PRIOR TO JANUARY 1, 2021. Source footnotes citing and describing the most recent Acts changes follow each new or amended Code section. Internal Code reference citations (Referred to in § __ ) may follow a Code section, but these citations have not yet been validated. DISCLAIMER This document is not an official legal publication of the state of Iowa. For the official publication of the Iowa Acts and the Iowa Code, see those publications. (Iowa Code §2B.17) ELECTION LAWS OF IOWA 2020 PAGE 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS CONSTITUTION OF THE STATE OF IOWA (CODIFIED) ARTICLE II RIGHT OF SUFFRAGE Section 1 Electors.................................................................................................... 27 Section 2 Privileged from arrest................................................................................ 27 Section 3 From military duty.................................................................................... -

The Collapse of the Iowa Democratic Party: Iowa and the Lecompton Constitution Garret Wilson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2012 the collapse of the iowa democratic party: iowa and the lecompton constitution Garret Wilson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wilson, Garret, "the collapse of the iowa democratic party: iowa and the lecompton constitution" (2012). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 12519. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/12519 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The collapse of the Iowa Democratic Party: Iowa and the lecompton constitution by Garret W. Wilson A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: History Program of Study Committee: Kathleen Hilliard, Major Professor Charles Dobbs Robert Urbatsch Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2012 Copyright © Garret W. Wilson 2012. All rights reserved. ii Table of Contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1 Early Development of Iowa 9 Chapter 2 The Lecompton Constitution 33 Chapter 3 The Lasting Effects of the Lecompton Constitution 58 Bibliography 79 1 Introduction The ideal of compromise consumed the politics of America during the antebellum era. The political arguments of expansion and abolition of slavery constantly threatened to tear the Union apart because with every piece of new legislation a state would threaten secession. -

3.12 -- Page 1 of 4 the THREE BRANCHES of GOVERNMENT

USA–Iowa TOOLKIT #3.12 -- Page 1 of 4 THE THREE BRANCHES OF GOVERNMENT https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/resources/threeBranchesGovernment.pdf In Iowa government, as at the national level of government, power is distributed among three branches: • Legislative – www.legis.iowa.gov – The legislative branch creates laws that establish policies and programs. • Executive – www.iowagov –The executive branch carries out the policies and programs contained in law. • Judicial – www.iowacourts.gov – The judicial branch resolves any conflicts arising from the interpretation or application of the laws. While each branch of government has its own separate responsibilities, one branch cannot function without the other two branches. LEGISLATIVE BRANCH: The Iowa Constitution establishes the state’s lawmaking authority in a general assembly consisting of a Senate and a House of Representatives. The Iowa General Assembly is often referred to as the “Iowa Legislature” or simply the “Legislature.” Legislative Districts The Iowa Senate consists of 50 members. Each Senator represents a separate geographic area of the state. This area is called a district. There are 50 Senate districts in Iowa. Each Senate district currently contains approximately 58,500 people. The Iowa House of Representatives consists of 100 members. As with the Senate, each Representative serves a separate district. There are 100 House districts in Iowa, two within each Senate district. Currently, each House district contains approximately 29,300 people. Every Iowan is represented by one Senator and one Representative in the Iowa Legislature (also known as the General Assembly) Since the districts are all of nearly equal population, all Iowans are represented equally in the General Assembly. -

The New York State Legislative Process: an Evaluation and Blueprint for Reform

THE NEW YORK STATE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS: AN EVALUATION AND BLUEPRINT FOR REFORM JEREMY M. CREELAN & LAURA M. MOULTON BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE AT NYU SCHOOL OF LAW THE NEW YORK STATE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS: AN EVALUATION AND BLUEPRINT FOR REFORM JEREMY M. CREELAN & LAURA M. MOULTON BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE AT NYU SCHOOL OF LAW www.brennancenter.org Six years of experience have taught me that in every case the reason for the failures of good legislation in the public interest and the passage of ineffective and abortive legislation can be traced directly to the rules. New York State Senator George F. Thompson Thompson Asks Aid for Senate Reform New York Times, Dec. 23, 1918 Some day a legislative leadership with a sense of humor will push through both houses resolutions calling for the abolition of their own legislative bodies and the speedy execution of the members. If read in the usual mumbling tone by the clerk and voted on in the usual uninquiring manner, the resolution will be adopted unanimously. Warren Moscow Politics in the Empire State (Alfred A. Knopf 1948) The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law unites thinkers and advocates in pursuit of a vision of inclusive and effective democracy. Our mission is to develop and implement an innovative, nonpartisan agenda of scholarship, public education, and legal action that promotes equality and human dignity, while safeguarding fundamental freedoms. The Center operates in the areas of Democracy, Poverty, and Criminal Justice. Copyright 2004 by the Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report represents the extensive work and dedication of many people. -

Iowa -- Political Scenario

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas http://dolearchives.ku.edu IOWA -- POLITICAL SCENARIO U.S. Senate Race POLLING: A poll commissioned by three Iowa television stations (KCCI-Des Moines, KGAN-Cedar Rapids, and KTIV-Sioux City) and conducted by Political-Media Research, Inc., shows Harkin leading Tauke by a mere 9-point margin (46% to 37%). Seventeen percent of Iowans surveyed were uncommitted. Tauke's people contend that Harkin's dropping below 50% shows his vulnerability, while a Harkin spokesman maintained the sitting Senator's 17-point lead among Independents. SURROGATES: Tauke's campaign received an early boost from Clayton Yeutter in 1989. Also throughout the year, President Bush, Vice President Quayle, Secretary Sullivan, and Secretary Dole appeared. The Tauke campaign also has future commitments from Secretary Cavasos (June), Secretary Mosbacher (July), Secretary Brady (August), and Secretary Kemp. Iowa Native Son Cooper Evans will also appear. CAMPAIGN THEMES: Tauke is stressing his abilities as a coalition-builder in Congress -- as opposed to Harkin, who you'll recall gave a very strong statement in 1985 regarding your stand on portions of the Farm Bill. The character issue has worked well for Tauke -- and they're painting Harkin as accountable to influence peddlers. (90 % of his fundraising money is from out-of-state donors). \ ISSUES TO STRESS: Tom Tauke is a friend to agriculture. The Harkin record is bad news for farmers, since he's beholden to special interests on both the East and West Coasts. (See specifics in Tauke campaign brief). Also, Tauke has asked that you stress that if Harkin is defeated, Iowa won't lose a seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee -- since Harkin is fighting for agriculture interests outside of Iowa.