Volume 2 Issue 2 Part 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federalism and Global Governance

CADMUS, Volume I, No. 5, October 2012, 135-144 Federalism and Global Governance John Scales Avery, Fellow, World Academy of Art and Science; University of Copenhagen, Denmark Abstract It is becoming increasingly clear that the concept of the absolutely sovereign nation-state is a dangerous anachronism in a world of thermonuclear weapons, instantaneous communication, and economic interdependence. Probably our best hope for the future lies in developing the United Nations into a World Federation. The strengthened United Nations should have a legislature with the power to make laws that are binding on individuals, and the ability to arrest and try individual political leaders for violations of these laws. The world federation should also have the power of taxation, and the military and legal powers necessary to guarantee the human rights of ethnic minorities within nations. 1. Making the United Nations into a Federation A federation of states is, by definition, a limited union where the federal government has the power to make laws that are binding on individuals, but where the laws are confined to interstate matters, and where all powers not expressly delegated to the federal government are retained by the individual states. In other words, in a federation each of the member states runs its own internal affairs according to its own laws and customs; but in certain agreed-on matters, where the interests of the states overlap, authority is specifically delegated to the federal government. Since the federal structure seems well suited to a world government with limited and carefully-defined powers that would preserve as much local autonomy as possible, it is wor- thwhile to look at the histories of a few of the federations. -

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Hellenic College, Brookline, MA Marian Gheorghe SIMION, Ph.D

Marian Gh. Simion, PhD TEACHING AREAS: RELIGION, VIOLENCE, PEACEBUILDING Cell: 978-339-3233 | E-mail: [email protected] | Home Address: 21 Oak Ridge Drive, Ayer, MA 01432 PROFESSIONAL SUMMARY TEACHING SUBJECTS (SELECTION) A versatile scholar practitioner with teaching talent, compassion, integrity, practical Religion, Violence & Peace experience and international expertise, Conflict Transformation strong verbal and written communication Research Methodology skills; relying on 16+ years of successful Collective Violence expertise in higher education. Highly Orthodox Christianity motivated to use a pedagogy based on clear World Religions & Violence learning objectives, focus on structure, use of Anthropology of Violence case studies, and critical thinking exercises. Just War Theory Ritual & Violence SELECTED PUBLICATIONS Religion & Diplomacy Religion & Politics Research Methodology in Orthodox Peace Totalitarianism Studies: university textbook (Romanian) Terrorism & Religion (Presa Universitara Clujeana, 2016) Religion and Public Policy: Human Rights, Conflicts, and Ethics LANGUAGES (Cambridge University Press, 2015) Just Peace: Orthodox Perspectives (WCC Publications, 2012) ROMANIAN ENGLISH FRENCH GREEK Religion and Political Conflict: From Dialectics to Cross-Domain Charting (Presses internationale polytechnique, 2011) +++ Latin, Old Slavic, Pastristic Greek, Italian, Spanish AWARDS (selection) APPOINTMENTS (current & past) Medal of the Romanian Parliament Awarded by the Chamber of Deputies (Juridical Committee on Discipline -

September 6, 2019 the Honorable

1701 K STREET, N.W., SUITE 950 • WASHINGTON, D.C. 20006 • PHONE: 202.331.1616 • WWW.BRETTONWOODS.ORG September 6, 2019 The Honorable James E. Risch The Honorable Bob Menendez Chairman Ranking Member Committee on Foreign Relations Committee on Foreign Relations United States Senate United States Senate Dear Senator Risch and Senator Menendez: We write to ask that you support both the authorization and appropriations for the general capital increase (GCI) for the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) of the World Bank Group. As you know, the World Bank Group’s shareholders endorsed an ambitious package of measures for the capital increase in 2018. It includes internal reforms and a set of policy measures that greatly strengthens the institution’s ability to scale up resources and deliver on its mission of fighting global poverty. It was developed in response to an increasingly complex development landscape and to confront emerging challenges to the global economy which will require a coordinated and sustained effort. The Bank has also developed, for the first time, a comprehensive strategy to address fragility, conflict and violence in countries where assistance is needed the most. It is important that the United States supports this effort because it: • Promotes National Security Interests World Bank support to countries where poverty and disease can breed political instability and foster extremism is vital to U.S. national security interests. World Bank projects promote stability in weak states and help mitigate cross-border problems – such as the Ebola outbreak and refugee crises – which precipitates positive spillover effects on national, regional, and global security fostering a safer world for all Americans. -

Pcr 422 Course Guide

COURSE GUIDE PCR 422 GLOBALISATION AND PEACE Course Team Dr. S. Ebimaro (Course Developer/Writer) - Abuja Dr. E. K. Faluyi (Course Editor) - UNILAG Mr. O. B. Durojaiye (Course Coordinator) - NOUN NATIONAL OPEN UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA PCR 422 COURSE GUIDE National Open University of Nigeria Headquarters 14/16 Ahmadu Bello Way Victoria Island, Lagos Abuja Office 5 Dar es Salaam Street Off Aminu Kano Crescent Wuse II, Abuja E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.nou.edu.ng Published by National Open University of Nigeria Printed 2015 ISBN: 978-058-740-9 All Rights Reserved Printed by ii PCR 422 COURSE GUIDE CONTENTS PAGE Introduction…………………………………………….. iv Course Objectives………………………………………. iv Working through the Course…………………………… v Course Materials………………………………………... v Textbook and References………………………………. v Assessment File………………………………………… v Tutor -Marked Assignment……………………………… v Final Examination……………………………………… vi Course Marking Scheme……………………………….. vi Presentation Schedule…………………………………... vi How to Get the Most from this Course………………… vii Tutors and Tutorials……………………………………. vii Summary………………………………………………... viii iii PCR 422 COURSE GUIDE INTRODUCTION PCR 422 Globalisation and Peace is a three-credit unit course for undergraduate students in Globalisation and Peace Studies. The materials have been developed to equip you with the fundamental principles of the subject matter. The course guide gives you an overview of the course. It also provides you with information on the organisation and requirements of the course. COURSE OBJECTIVES The course aims to help students understand the causal relationship between globalisation and conflict, and how fair and inclusive globalisation can engender peace and economic development. Globalisation is the comprehensive term for the emergence of a global society in which economic, political, environmental, and cultural events in one part of the world quickly come to have significance impact on people in other parts of the world. -

Offshore Energy Geopolitics: an Examination of Emerging Risks to Future Oil and Gas Activities in Hotspot Maritime Regions

OFFSHORE ENERGY GEOPOLITICS: AN EXAMINATION OF EMERGING RISKS TO FUTURE OIL AND GAS ACTIVITIES IN HOTSPOT MARITIME REGIONS by Erik Fagley A thesis submitted to the Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for degree of Master of Arts in Global Security Studies Baltimore, Maryland May 2014 © 2014 Erik Fagley All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT As the world’s conventional oil and gas fields decline, the oil and gas industry seeks to exploit new sources of energy to satisfy demand and promote economic growth. The most promising geographical regions left to explore are offshore waters that contain a substantial reserve base that contain decades of supply. Although offshore development is not new, certain regions slated for production are vulnerable to a wide-array of risks that might derail future activity. The examination of these risks is a timely study given its relevance to energy security and the ever-increasing vulnerabilities in maritime regions. To better explain the offshore energy geopolitical landscape, this thesis explores three regions – the South China Sea, Arctic, and the Gulf of Guinea. Each region typifies political, legal, economic and environmental risks associated with offshore development; however, each region is faced with markedly different risks to future operations. Whether this includes territorial disputes between claimants over control of seabed resources in the South China Sea, the absence of an effective framework to govern and regulate offshore activities in the Arctic, or the emergence of oil theft and maritime piracy in the Gulf of Guinea, each chapter highlights the importance of addressing these risks. In response, the thesis provides mitigating strategies and policy recommendations to alleviate tensions, resolve gaps in governance and regulation and combat maritime piracy. -

Newsmax Funding World Bank Should Be Congressional Priority

8/3/2017 PrintTemplate Newsmax Funding World Bank Should be Congressional Priority Thursday, August 3, 2017 10:32 AM By: Francesco Stipo In September of this year, the U.S. Congress will vote on a foreign operations budget, including funding for the International Development Association (IDA), an international financial institution offering loans and grants to the world’s poorest countries. It is part of the World Bank Group. In 2016, the U.S. pledged $3.871 billion for the 3-year IDA budget. This year the U.S. House of Representatives has proposed to cut the funds to IDA by 50 percent for the year 2018. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) are important pillars of international development and financial stability. World Bank funding fosters American global leadership. As the largest shareholder of the World Bank, the U.S. is the only country possessing veto power, thus assuring a strong influence in its decisions. Traditionally, the president of the World Bank has always been a U.S. citizen (the current president, Jim Yong Kim, is Korean-American). Since he became president of the World Bank, Jim Yong Kim has taken new initiatives to modernize the organization. In 2014, he launched the Global Infrastructure Facility (GIF), a public-private partnership combining private capital and public expertise to foster international development. GIF reflects the increasing importance of the private sector in financing projects of public relevance. In 2010 the IMF initiated a reform, backed by current Managing Director Christine Lagarde, which was approved by Congress in 2015. The IMF reform increased the quotas of emerging economies while preserving American de facto veto power. -

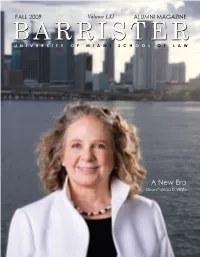

Fall 2009 Alumni Magazine

FALL 2009 Volume LXI ALUMNI MAGAZINE BARRISTERBARRISTER UNIVERSITY OF MIAMI SCHOOL OF LAW A New Era Dean Patricia D. White BARRISTER FALL ALUMNI MAGAZINE Patricia D. White Dean and Professor of Law Patrick O. Gudridge Associate Dean and Professor of Law Raquel M. Matas Associate Dean for Administration COVER22 10 Georgina A. Angones Assistant Dean for Alumni Relations and Development CONTENTS Jeannette F. Hausler ON THE COVER INSERT HONOR ROLL OF DONORS Dean of Students Emerita 1 Dean Patricia White - The Right Leader for Our Time NOTEWORTHY 25 Miami Scholars Program Michelle Valencia FEATURES Director of Publications 5 Alumna Carolyn Lamm Becomes Students from the Children & President of ABA Youth Law Clinic Fight for Patricia Moya Disabled Youths Graphic Designer A Conversation with Professor Bernard Oxman ALUMNI 28 Message from the President of Contributors Riding for Charity the Alumni Association Angelica Boutwell Nancy Funkhouser FACULTY BRIEFS New York Alumni Reception Mary Howard 12 New Faculty Law School Alumni Honored Tai Palacio Visiting Faculty Faculty Notes Mindy Rosenthal Florida Bar Reception Patty Shillington STUDENT HIGHLIGHTS Class of 1959 Angela Sturrup 18 UM Law Student Elected President of the Florida Bar’s Law Alex Laster Bowling Extravaganza Photographers Student Division Jenny Abreu Young Alumni Committee UM Law Wins Dubersein Richard Patterson Bankruptcy Moot Court Joshua Prezante Soia Mentschikioff’s Vision of Competition Legal Education Steve Schlackman Bob Soto UM Law Hosts the HNBA Class Notes BLSA Team Ranks Among In Memoriam The Barrister is published by the Nation’s Top Eight Office of Law Alumni Relations and Questionnaire Development, University of Miami NASALSA School of Law. -

The Future of the Pacific and Its Relevance for Geo-Economic Interests

World Academy of Art & Science Eruditio, Issue 3, September 2013 The Future of the Pacific Francesco Stipo et al ERUDITIO, Volume I, Issue 3, September 2013, 42-53 The Future of the Pacific and its Relevance for Geo-economic Interests Francesco Stipo, Fellow, World Academy of Art & Science; Chair, Legal Political Committee, US Association, Club of Rome Anitra Thorhaug, Chair, Energy & Resources Committee; US Association, Club of Rome Marian Simion, Chair, Health and Religion Committee; US Association, Club of Rome Keith Butler, Roberta Gibbs, Ryan Jackson, Andrew Oerke, Lockey White* Abstract The Report forecasts that free trade initiatives in the Pacific will become polarized between the Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership. The Report identifies two factors that will slow Chinese economic growth and reduce U.S.-China bilateral trade in the next 30 years: the development of additive manufacturing and the increase of Chinese cost of labor. In the next 30 years there will be a redistribution of global energy demand that will change the global political scenario: the discovery of large quantities of oil and natural gas in North America will reduce foreign energy demand in the United States and increase the availability of energy to cover Chinese demand. The short-term consequences will be reduction of com- petition between the US and China for sources of energy, increase of Chinese reliance on Middle Eastern and Latin American oil and growing Japanese imports of liquefied natural gas from the United States. This scenario will change when renewable energy will become more cost effective and will replace oil and natural gas as the main source of energy. -

Gender Perspectives on Climate Change & Human Security

THE WEALTH OF NATIONS REVISITED CADMUS Inside This Issue The very possession of nuclear weapons violates the funda- mental human rights of the citizens of the world and must be CADMUS regarded as illegal. Winston P. Nagan, Simulated ICJ Judgment PROMOTING LEADERSHIP IN THOUGHT THAT LEADS TO ACTION A papers series of the South-East European Division The emerging individual is less deferential to the past and more of the World Academy of Art and Science (SEED-WAAS) insistent on his or her rights; less willing to conform to regimen- tation, more insistent on freedom and more tolerant of diversity. Evolution from Violence to Law to Social Justice It is more rational to argue that developing countries cannot afford unemployment and underemployment, than to suppose Volume I, Issue 4 April 2012 ISSN 2038-5242 that they cannot afford full employment. Jesus Felipe, Inclusive Growth Editorial: Human Capital The tremendously wasteful underutilization of precious human SEED-IDEAS resources and productive capacity is Greece’s most serious Great Transformations problem and also its greatest opportunity. The Great Divorce: Finance and Economy Immediate Solution for the Greek Financial Crisis Evolution from Violence to Law to Social Justice Immediate Solution for the Greek Financial Crisis The Original thinker seeks not just ideas but original ideas which Economic Crisis & the Science of Economics are called in Philosophy Real-Ideas. Cadmus Journal refers ARTICLES to them as Seed-Ideas. Ideas, sooner or later, lead to action. Original Thinking Pregnant ideas have the dynamism to lead to action. Real-Ideas — Ashok Natarajan are capable of self-effectuation, as knowledge and will are inte- Inclusive Growth: Why is it important for developing Asia? grated in them. -

Issue 5 Part 1

THE WEALTH OF NATIONS REVISITED CADMUS PROMOTING LEADERSHIP IN THOUGHT THAT LEADS TO ACTION A papers series of the South-East European Division of the World Academy of Art and Science (SEED-WAAS) Volume I, Issue 5, Part 1 October 2012 ISSN 2038-5242 Seed-Idea: Recognizing Unrecognized Genius — Ivo Šlaus & Garry Jacobs Seed-Idea: Counter-Aging in the Post-industrial Society — Orio Giarini Seed-Idea: Seeding Intrinsic Values: How a Law of Ecocide will Shift our Consciousness — Polly Higgins Crises and Opportunities: A Manifesto for Change — Ian Johnson & Garry Jacobs Double Factor Ten: Responsibility and Growth in the 21st Century — F. J. Radermacher Rio+20 — Robert E. Horn The Future of the Arctic: A Key to Global Sustainability — Francesco Stipo et al Book review — 2052: A Global Forecast for the Next Forty Years — Michael Marien EDITORIAL BOARD Chairman: Ivo Šlaus, President of World Academy of Art & Science; President, South East European Division, World Academy of Art & Science, Zagreb, Croatia; Member of the Club of Rome. Editor-in-Chief: Orio Giarini, Director, The Risk Institute (Geneva and Trieste, Publisher), Member of the Board of Trustees of World Academy of Art & Science; Member of the Club of Rome. Managing Editor: Garry Jacobs, Chairman of the Board of Trustees, World Academy of Art & Science; Vice-President, The Mother’s Service Society, Pondicherry, India. Members: Walter Truett Anderson, Former President, World Academy of Art & Science; Fellow of the Meridian International Institute (USA) and Western Behavioral Sciences Institute. Ian Johnson, Secretary General, Club of Rome; former Vice President, The World Bank; Fellow of World Academy of Art & Science. -

CADMUS Inside This Issue

THE WEALTH OF NATIONS REVISITED CADMUS Inside This Issue The world needs a paradigm shift in economics similar to the one physics experienced at the dawn of the last century, when CADMUS quantum mechanics and the special and general theories of relativity were invented to address new phenomena not explai- PROMOTING LEADERSHIP IN THOUGHT THAT LEADS TO ACTION A papers series of the South-East European Division nable by Newtonian mechanics or Maxwell’s electrodynamics. Roberto Peccei, of the World Academy of Art and Science (SEED-WAAS) Rethinking Growth: The Need for a New Economics Society is evolving. Understanding the present in the light of the past, we see only the problems resulting in gloom. Understanding the present in the light of the future compels us to evolve, we see the opportunities it points to. Volume I, Issue 3 October 2011 ISSN 2038-5242 Ian Johnson,The World in 2052 We have organized production to perfection, but left out the most crucial ingredient – humanity. We have raised the value SEED IDEAS of GDP phenomenally, but overlooked the value of human Organization Abolishes Scarcity security. The process of society’s past evolution offers hope and assurance that there is a better way and a better life for all Organizing International Food Security humanity waiting to emerge. Human-centered economic theory Boundless Frontiers of Untold Wealth and measures of wealth, welfare and human security can help Mediterranean-EU Community for a New Era of Mankind us realize it now. ARTICLES Orio Giarini & Garry Jacobs, The Evolution of Wealth & Human Security The World in 2052 — Ian Johnson Working for peace is part of the heritage WAAS fellows have Rethinking Growth: The Need for a New Economics been given by Academy founders who, after helping deve- — Roberto Peccei lop the theories and technology for nuclear weapons, were The Evolution of Wealth & Human Security: The Paradox amongst the first to recognize that they should be banned. -

Vol. 44, No. 4: Full Issue

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 44 Number 4 Summer Article 6 Student Edition April 2020 Vol. 44, no. 4: Full Issue Denver Journal International Law & Policy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation 45 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y (2016). This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. Denver Journal 10 of International Law and Policy VOLUME 44 NUMBER 4 SUMMER-2016 TA]BLE OF CONTENTS DENVER JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND PoLicy's STUDENT EDITION OIL AND SUSTAINABILITY IN THE ARCTIC CIRCLE ................... Caroline M. Rixey 441 WHAT DOES CLIMATE JUSTICE LOOK LIKE FOR THE ENVIRONMENTALLY DISPLACED IN A POST PARIS AGREEMENT ENVIRONMENT? POLITICAL QUESTIONS AND COURT DEFERENCE TO CLIMATE SCIENCE IN THE URGENDA DECISION ............. Jeremy M. Bellavia 453 CSR BEST PRACTICE FOR ABOLISHING CHILD LABOR IN THE TRAVEL AND TOURISM INDUSTRY ............. Jeremy S. Goldstein 475 THE SUBMISSION OF THE SOVEREIGN: AN EXAMINATION OF THE COMPATIBILITY OF SOVEREIGNTY AND INTERNATIONAL LAW ......... Cameron Oren Hunter 521 OIL AND SUSTA1NABILITY IN THE ARCTIC CIRCLE CarolineM Rixey* Remaining one of the last untouched environments on Earth, the Arctic Circle is home to a vast number of natural resources and wildlife. Yet as a result of climate change, the unique environment of the Arctic is rapidly shifting, uncovering more and more of the continental shelf as the ice sheets melt away.' This melting allows for greater access to the Arctic land beneath, and the resources it provides, that was unavailable before.