Defiled Trades and Social Outcasts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

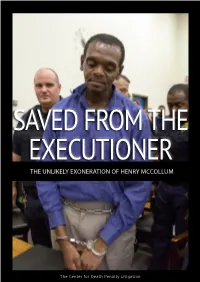

SAVED from the EXECUTIONER: the Unlikely Exoneration of Henry

SAVED FROM THE EXECUTIONER THE UNLIKELY EXONERATION OF HENRY MCCOLLUM The Center for Death Penalty Litigation HENRY MCCOLLUM f all the men and women on death row in North Carolina, Henry McCollum’s guilty verdict looked O airtight. He had signed a confession full of grisly details. Written in crude and unapologetic language, it told the story of four boys, he among them, raping 11-year-old Sabrina Buie, and suffocating her by shoving her own underwear down her throat. He had confessed again in front of television cameras shortly after. His younger brother, Leon Brown, also admitted involvement in the crime. Both were sen- tenced to death in 1984. Leon was later resentenced to life in prison. But Henry remained on death row for 30 years and became Exhibit A in the defense of the death penalty. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia pointed to the brutality of Henry’s crime as a reason to continue capital punishment nation- wide. During North Carolina legislative elections in 2010, Henry’s face showed up on political flyers, the example of a brutal rapist and child killer who deserved to be executed. What almost no one saw — not even his top-notch defense attorneys — was that Henry McCollum was inno- cent. He had nothing to do with Sabrina’s murder. Nor did Leon. In 2014, both were exonerated by DNA evidence and, in 2015, then-Gov. Pat McCrory granted them a rare LEON BROWN pardon of innocence. Though Henry insisted on his innocence for decades, the truth was painfully slow to emerge: Two intellectually disabled teenagers – naive, powerless, and intimidated by a cadre of law enforcement officers – had been pres- sured into signing false confessions. -

The German Civil Code

TUE A ERICANI LAW REGISTER FOUNDED 1852. UNIERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA DEPART=ENT OF LAW VOL. {4 0 - S'I DECEMBER, 1902. No. 12. THE GERMAN CIVIL CODE. (Das Biirgerliche Gesetzbuch.) SOURCES-PREPARATION-ADOPTION. The magnitude of an attempt to codify the German civil. laws can be adequately appreciated only by remembering that for more than fifteefn centuries central Europe was the world's arena for startling political changes radically involv- ing territorial boundaries and of necessity affecting private as well as public law. With no thought of presenting new data, but that the reader may properly marshall events for an accurate compre- hension of the irregular development of the law into the modem and concrete results, it is necessary to call attention to some of the political- and social factors which have been potent and conspicuous since the eighth century. Notwithstanding the boast of Charles the Great that he was both master of Europe and the chosen pr6pagandist of Christianity and despite his efforts in urging general accept- ance of the Roman law, which the Latinized Celts of the western and southern parts of his titular domain had orig- THE GERM AN CIVIL CODE. inally been forced to receive and later had willingly retained, upon none of those three points did the facts sustain his van- ity. He was constrained to recognize that beyond the Rhine there were great tribes, anciently nomadic, but for some cen- turies become agricultural when not engaged in their normal and chief occupation, war, who were by no means under his control. His missii or special commissioners to those people were not well received and his laws were not much respected. -

Prison Guards and the Death Penalty

BRIEFING PAPER Prison guards and the death penalty Introduction and elsewhere.3 In Japan, in the latter stages before execution, all communication between prisoners or When we think about the people affected by the death between guards and prisoners is forbidden.4 penalty, we may not think about guards on death rows. But these officials, whether they oversee prisoners In 2014, the Texas prison guards union appealed for awaiting execution or participate in the execution itself, better death row prisoner conditions, because the can be deeply affected by their role in helping to put a guards faced daily danger from prisoners made mentally person to death. ill by solitary confinement and who had ‘nothing to lose’.5 In this environment, routine safety practices were imposed that dehumanised prisoners and guards alike, Guards on death row such as every exit of a cell requiring a strip search. Persons sentenced to death are usually considered Guards protested that their own dignity was undermined among the most dangerous prisoners and are placed by the obligation to look at ‘one naked inmate after in the highest security conditions. Prison guards are another’6 all day. frequently suspicious of death row prisoners, are particularly vigilant around them,1 and experience death row as a dangerous place. Interactions with prisoners Despite the stark conditions, death rows are still places Harsh prison conditions can make things worse not where human connections form. In all but the most only for prisoners but also for guards. The mental extreme solitary settings, guards engage with prisoners health of death row prisoners frequently deteriorates regularly, bringing them food and accompanying them and they may suffer from ‘death row phenomenon’, the when they leave their cells (for example to exercise, ‘condition of mental and emotional distress brought on receive visits or attend court hearings). -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) The many faces of Duchess Matilda: matronage, motherhood and mediation in the twelfth century Jasperse, T.G. Publication date 2013 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Jasperse, T. G. (2013). The many faces of Duchess Matilda: matronage, motherhood and mediation in the twelfth century. Boxpress. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 The many faces of Duchess Matilda: matronage, motherhood and mediation in the twelfth century Jitske Jasperse The many faces of Duchess Matilda: matronage, motherhood and mediation in the twelfth century ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. -

Police Science As a Source of Modern Administrative Sciences

Teka Komisji Prawniczej PAN Oddział w Lublinie, t. XII, 2019, nr 2, s. 327–336 https://doi.org/10.32084/tekapr.2019.12.2-25 POLICE SCIENCE AS A SOURCE OF MODERN ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCES Grzegorz Smyk, hab. Ph.D., University Professor Department of History of State and Law, Faculty of Law and Administration at the Maria Curie–Skłodowska University in Lublin e-mail: [email protected]; https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0143-4233 Summary. It was the science of police (Ger. Polizeiwissenschaft) that first endeavoured to offer a comprehensive understanding of the organisation and operation of public administra- tion. It stemmed from the cameralist doctrine which combined, in addition to administrative management, a broad and not-at-all systemic set of knowledge of economics, finance, statistics, demography, economic policy of the state, and even philosophy. While cameralism mainly put emphasis on economics and approached administrative issues only as a means of efficient fiscal and economic administration of the state, police science, which was under the influence of the law of nature, addressed the development of a system of methods and measures employed to shape the structure of public administration in the modern state. Key words: police science, administration, administrative law The arrival of modern administrative science was intertwined with the sys- temic transformation of the state ruled by public law that occurred in the 18th century under the influence of Enlightenment philosophy. The transformation processes were triggered by the crisis of the social, economic and organisa- tional framework of the feudal state, which caused all these areas of human activity to go through reforms aimed, in particular, to create a new, well-oiled state apparatus. -

State Forms and State Systems in Modern Europe by Robert Von Friedeburg

State Forms and State Systems in Modern Europe by Robert von Friedeburg This article discusses the transformation of Europe from a collection of Christian dynasties and (city-) republics, which were all part of the Church of Rome and represented at the Councils of Constance (1414–1418) and Basle (1432–1448), to a Europe of sovereign states. Of these states, five would go on to dominate Europe for much of 18th, 19th and the first part of the 20th century. These five powers saw their position of dominance destroyed by the First and Second World Wars, after which Europe was dominated by two powers which were fully or partly non-European, the Soviet Union and the United States, both of which led alliance systems (Warsaw Pact, North Atlantic Treaty Organi- zation). Given that one of these alliance systems has already ceased to exist, it can be argued that the emergence of the modern occidental state remains the most significant development in modern world history. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. From universal Christianity to the sovereign western state: Problems and definitions 2. State forms and state systems, 1490s to 1790s 3. Toward the modern state system, 1790s to 1950 4. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Bibliography 3. Notes Citation From universal Christianity to the sovereign western state: Problems and definitions Discussions of the modern occidental state are complicated by the fact that some fundamental assumptions about its nature have lost their validity over the last twenty years. Until the 1950s, it was assumed that the gradual transfer of le- gitimacy in the area of civil order from universal Christianity to the modern state was caused by a putative early-modern triumph of the coercive, bureaucratic, institutional, tax-collecting state over elites which, while initially reluctant, were eventually subdued. -

The Spanish Garrote

he members of parliament, meeting in Cadiz in 1812, to draft the first Spanish os diputados reunidos en Cádiz en 1812 para redactar la primera Constitución Constitution, were sensitive to the irrational torment that those condemned to Española, fueron sensibles a los irracionales padecimientos que hasta entonces capital punishment had up until then suffered when they were punished. In De- the spanish garrote sufrían los condenados a la pena capital en el momento de ser ajusticiados, y cree CXXVIII, of 24 January, they recognized that “no punishment will be trans- en el Decreto CXXVIII, de 24 de enero, reconocieron que “ninguna pena ha ferable to the family of the person that suffers it; and wishing at the same time that Lde ser trascendental a la familia del que la sufre; y queriendo al mismo tiempo Tthe torment of the criminals should not offer too repugnant a spectacle to humanity que el suplicio de los delincuentes no ofrezca un espectáculo demasiado and to the generous nature of the Spanish nation (…) ” they agreed to abolish the repugnante a la humanidad y al carácter generoso de la Nación española transferable punishment of hanging, replacing it with the garrote. (...) ” acordaron abolir la trascendental pena de horca, sustituyéndola por la Some days earlier, on January 10th, the City Council of Toledo, in compliance de garrote. with a decision of the Real Junta Criminal [Royal Criminal Committee] of the city, Ya unos días antes, el 10 de enero, el ayuntamiento de Toledo, en cum- agreed to the construction of two garrotes and approved the regulations for the plimiento de una providencia de la Real Junta Criminal de la ciudad, acordó construction of the platform. -

The Peformative Grotesquerie of the Crucifixion of Jesus

THE GROTESQUE CROSS: THE PERFORMATIVE GROTESQUERIE OF THE CRUCIFIXION OF JESUS Hephzibah Darshni Dutt A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2015 Committee: Jonathan Chambers, Advisor Charles Kanwischer Graduate Faculty Representative Eileen Cherry Chandler Marcus Sherrell © 2015 Hephzibah Dutt All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Jonathan Chambers, Advisor In this study I argue that the crucifixion of Jesus is a performative event and this event is an exemplar of the Grotesque. To this end, I first conduct a dramatistic analysis of the crucifixion of Jesus, working to explicate its performativity. Viewing this performative event through the lens of the Grotesque, I then discuss its various grotesqueries, to propose the concept of the Grotesque Cross. As such, the term “Grotesque Cross” functions as shorthand for the performative event of the crucifixion of Jesus, as it is characterized by various aspects of the Grotesque. I develop the concept of the Grotesque Cross thematically through focused studies of representations of the crucifixion: the film, Jesus of Montreal (Arcand, 1989), Philip Turner’s play, Christ in the Concrete City, and an autoethnographic examination of Cross-wearing as performance. I examine each representation through the lens of the Grotesque to define various facets of the Grotesque Cross. iv For Drs. Chetty and Rukhsana Dutt, beloved holy monsters & Hannah, Abhishek, and Esther, my fellow aliens v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS St. Cyril of Jerusalem, in instructing catechumens, wrote, “The dragon sits by the side of the road, watching those who pass. -

Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth-Century New England

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2014 "Thus Did God Break the Head of that Leviathan": Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth-Century New England Ian Edward Tonat College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Indigenous Studies Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Tonat, Ian Edward, ""Thus Did God Break the Head of that Leviathan": Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth-Century New England" (2014). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626765. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-ycqh-3b72 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Thus Did God Break the Head of That Leviathan”: Performative Violence and Judicial Beheadings of Native Americans in Seventeenth- Century New England Ian Edward Tonat Gaithersburg, Maryland Bachelor of Arts, Carleton College, 2011 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Lyon G. Tyler Department of History The College of William and Mary May, 2014 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted -

Das Würzburger Landgericht in Der Ersten Hälfte Des 14

DAS WÜRZBURGER LANDGERICHT IN DER ERSTEN HÄLFTE DES 14. JAHRHUNDERTS UND SEINE ÄLTESTEN PROTOKOLLE. EDITION UND AUSWERTUNG Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät II der Julius-Maximilians-Universität Würzburg vorgelegt von Michael Schäfer aus Marktheidenfeld Würzburg 2002 wer sich um weisheit bemüht benötigt viel zeit und nur wer sonst nichts zu tun hat wird weisheit gewinnen jesus sirach meinen Eltern und Birgitta INHALT Einführung I. Darstellung Die Entwicklung des Würzburger Herzogtums .................................................................10 Grundlagen der Entstehung 10 - Das Zeugnis Adams von Bremen 17 - Frühes 12. Jahrhundert 22 - Die „güldene Freiheit“ 30 Das Landgericht und seine Protokolle ................................................................................37 Hochgerichtsbarkeit 40 - Gerichtsverfassung Frankens 42 - Das Landgericht im Besonderen 45 - Landrecht und Grundlage der Rechtssprechung 51 - Die Zuständigkeiten des Landgerichts 63 - Das Landgericht und die anderen Ge- richte 74 - Der Landrichter 85 - Die Schöffen 91 - Die Gerichtsstätten 101 - Die Sanktionen 109 - Die Niederlegung des Urteilsspruches 136 - Die Bedeu- tung der Landgerichtsprotokolle vor dem Gericht 139 Die Quellen des Landgerichts 147 - Das älteste Landgerichtsprotokoll (Hand- schriftenbeschreibung) 149 - Editionsprinzipien 171 Methodologische Anmerkungen zur statistischen Auswertung......................................180 Datenbasis 183 - Korrelationen und Zeitrahmen 185 - Strukturierter -

Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by St. John's University School of Law St. John's Law Review Volume 75 Number 3 Volume 75, Summer 2001, Number 3 Article 4 March 2012 Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row Norman L. Greene Governor George H. Ryan Donald Cabana Jim Dwyer Martha Barnett See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview Recommended Citation Greene, Norman L.; Ryan, Governor George H.; Cabana, Donald; Dwyer, Jim; Barnett, Martha; and Davis, Evan (2001) "Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row," St. John's Law Review: Vol. 75 : No. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview/vol75/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in St. John's Law Review by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Governor Ryan's Capital Punishment Moratorium and the Executioner's Confession: Views from the Governor's Mansion to Death Row Authors Norman L. Greene, Governor George H. Ryan, Donald Cabana, Jim Dwyer, Martha Barnett, and Evan Davis This article is available in St. John's Law Review: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/lawreview/vol75/iss3/4 GOVERNOR RYAN'S CAPITAL PUNISHMENT MORATORIUM AND THE EXECUTIONER'S CONFESSION: VIEWS FROM THE GOVERNOR'S MANSION TO DEATH ROW NORMAN L. -

Death Row Witness Reveals Inmates' Most Chilling Final Moments

From bloodied shirts and shuddering to HEADS on fire: Death Row witness reveals inmates' most chilling final moments By: Chris Kitching - Mirror Online Ron Word has watched more than 60 Death Row inmates die for their brutal crimes - and their chilling final moments are likely to stay with him until he takes his last breath. Twice, he looked on in horror as flames shot out of a prisoner's head - filling the chamber with smoke - when a hooded executioner switched on an electric chair called "Old Sparky". Another time, blood suddenly appeared on a convicted murderer's white shirt, caking along the leather chest strap holding him to the chair, as electricity surged through his body. Mr Word was there for another 'botched' execution, when two full doses of lethal drugs were needed to kill an inmate - who shuddered, blinked and mouthed words for 34 minutes before he finally died. And then there was the case of US serial killer Ted Bundy, whose execution in 1989 drew a "circus" outside Florida State Prison and celebratory fireworks when it was announced that his life had been snuffed out. Inside the execution chamber at the Florida State Prison near Starke (Image: Florida Department of Corrections/Doug Smith) 1 of 19 The electric chair at the prison was called "Old Sparky" (Image: Florida Department of Corrections) Ted Bundy was one of the most notorious serial killers in recent history (Image: www.alamy.com) Mr Word witnessed all of these executions in his role as a journalist. Now retired, the 67-year-old was tasked with serving as an official witness to state executions and reporting what he saw afterwards for the Associated Press in America.