Megan Baker Research Honors Pt. 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Glorious Technicolor: from George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 the G

Glorious Technicolor: From George Eastman House and Beyond Screening Schedule June 5–August 5, 2015 Friday, June 5 4:30 The Garden of Allah. 1936. USA. Directed by Richard Boleslawski. Screenplay by W.P. Lipscomb, Lynn Riggs, based on the novel by Robert Hichens. With Marlene Dietrich, Charles Boyer, Basil Rathbone, Joseph Schildkraut. 35mm restoration by The Museum of Modern Art, with support from the Celeste Bartos Fund for Film Preservation; courtesy The Walt Disney Studios. 75 min. La Cucaracha. 1934. Directed by Lloyd Corrigan. With Steffi Duna, Don Alvarado, Paul Porcasi, Eduardo Durant’s Rhumba Band. Courtesy George Eastman House (35mm dye-transfer print on June 5); and UCLA Film & Television Archive (restored 35mm print on July 21). 20 min. [John Barrymore Technicolor Test for Hamlet]. 1933. USA. Pioneer Pictures. 35mm print from The Museum of Modern Art. 5 min. 7:00 The Wizard of Oz. 1939. USA. Directed by Victor Fleming. Screenplay by Noel Langley, Florence Ryerson, Edgar Allan Woolf, based on the book by L. Frank Baum. Music by Harold Arlen, E.Y. Harburg. With Judy Garland, Frank Morgan, Ray Bolger, Bert Lahr, Ray Bolger, Margaret Hamilton, Billie Burke. 35mm print from George Eastman House; courtesy Warner Bros. 102 min. Saturday, June 6 2:30 THE DAWN OF TECHNICOLOR: THE SILENT ERA *Special Guest Appearances: James Layton and David Pierce, authors of The Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935 (George Eastman House, 2015). James Layton and David Pierce illustrate Technicolor’s origins during the silent film era. Before Technicolor achieved success in the 1930s, the company had to overcome countless technical challenges and persuade cost-conscious producers that color was worth the extra effort and expense. -

Jack Oakie & Victoria Horne-Oakie Films

JACK OAKIE & VICTORIA HORNE-OAKIE FILMS AVAILABLE FOR RESEARCH VIEWING To arrange onsite research viewing access, please visit the Archive Research & Study Center (ARSC) in Powell Library (room 46) or e-mail us at [email protected]. Jack Oakie Films Close Harmony (1929). Directors, John Cromwell, A. Edward Sutherland. Writers, Percy Heath, John V. A. Weaver, Elsie Janis, Gene Markey. Cast, Charles "Buddy" Rogers, Nancy Carroll, Harry Green, Jack Oakie. Marjorie, a song-and-dance girl in the stage show of a palatial movie theater, becomes interested in Al West, a warehouse clerk who has put together an unusual jazz band, and uses her influence to get him a place on one of the programs. Study Copy: DVD3375 M The Wild Party (1929). Director, Dorothy Arzner. Writers, Samuel Hopkins Adams, E. Lloyd Sheldon. Cast, Clara Bow, Fredric March, Marceline Day, Jack Oakie. Wild girls at a college pay more attention to parties than their classes. But when one party girl, Stella Ames, goes too far at a local bar and gets in trouble, her professor has to rescue her. Study Copy: VA11193 M Street Girl (1929). Director, Wesley Ruggles. Writer, Jane Murfin. Cast, Betty Compson, John Harron, Ned Sparks, Jack Oakie. A homeless and destitute violinist joins a combo to bring it success, but has problems with her love life. Study Copy: VA8220 M Let’s Go Native (1930). Director, Leo McCarey. Writers, George Marion Jr., Percy Heath. Cast, Jack Oakie, Jeanette MacDonald, Richard “Skeets” Gallagher. In this comical island musical, assorted passengers (most from a performing troupe bound for Buenos Aires) from a sunken cruise ship end up marooned on an island inhabited by a hoofer and his dancing natives. -

SARP Data~Sep 2018

1 Screenwriting Research Network www.screenwritingresearch.com Screenwriting Archives and Resources Project (SARP) A worldwide statement of screenwriting resources. September 2018 © SRN 2018 Coordination: Ian W. Macdonald [email protected] 1 2 Introduction The Screenwriting Archives and Resources Project (SARP) is an initiative of the Executive Council of the Screenwriting Research Network (SRN). The SRN is a group of scholars worldwide whose research focuses on the genesis, generation and development of screen ideas, i.e. those intended to become moving image productions, whether fiction, fact or entertainment, in any medium (e.g. film, TV, interactive etc.). More information can be found on the SRN website at www.screenwritingresearch.com. Scholars of screenwriting have, until the 2000s, tended to work in isolation from like- minded others, often in academic environments where screenwriting is seen as a specialism in the industrial sense, of some interest within the broad study of Film, or Creative Industries and other sub-fields of Media, Media Practice, Communication and Cultural Studies. Screenwriting scholars have now come together to focus on the practices, processes, discourse, industry and cultural meanings of developing screen ideas; and in following these interests, we have discovered that the collection and preservation of textual material (including scripts, screenplays etc.) has been badly neglected by both academics and archivists, with a few honourable exceptions. This database is intended to draw together information on the collections that do exist, providing us with a greater awareness of what’s available, and therefore also – sadly – what is not. This document is compiled from a basic questionnaire available to anyone, whether scholar, practitioner, archivist or enthusiast. -

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings

Hofstra University Film Library Holdings TITLE PUBLICATION INFORMATION NUMBER DATE LANG 1-800-INDIA Mitra Films and Thirteen/WNET New York producer, Anna Cater director, Safina Uberoi. VD-1181 c2006. eng 1 giant leap Palm Pictures. VD-825 2001 und 1 on 1 V-5489 c2002. eng 3 films by Louis Malle Nouvelles Editions de Films written and directed by Louis Malle. VD-1340 2006 fre produced by Argosy Pictures Corporation, a Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer picture [presented by] 3 godfathers John Ford and Merian C. Cooper produced by John Ford and Merian C. Cooper screenplay VD-1348 [2006] eng by Laurence Stallings and Frank S. Nugent directed by John Ford. Lions Gate Films, Inc. producer, Robert Altman writer, Robert Altman director, Robert 3 women VD-1333 [2004] eng Altman. Filmocom Productions with participation of the Russian Federation Ministry of Culture and financial support of the Hubert Balls Fund of the International Filmfestival Rotterdam 4 VD-1704 2006 rus produced by Yelena Yatsura concept and story by Vladimir Sorokin, Ilya Khrzhanovsky screenplay by Vladimir Sorokin directed by Ilya Khrzhanovsky. a film by Kartemquin Educational Films CPB producer/director, Maria Finitzo co- 5 girls V-5767 2001 eng producer/editor, David E. Simpson. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. ita Flaiano, Brunello Rondi. / una produzione Cineriz ideato e dirètto da Federico Fellini prodotto da Angelo Rizzoli 8 1/2 soggètto, Federico Fellini, Ennio Flaiano scenegiatura, Federico Fellini, Tullio Pinelli, Ennio V-554 c1987. -

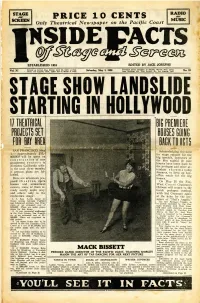

Inside Facts of Stage and Screen (May 3, 1930)

: STAGE RADIO SCREEN PRICE 10 CENTS MUSIC Only Theatrical Newspaper on the Pacific Coast ESTABLISHED 1S24 EDITED BY JACK JOSEPHS Entered as Second Class Matter, April 1927, at Post- Published Every Saturday at 800-801 Warner Bros. Down- Vol. XI 29, Saturday, May 3, 1930 No. 18 office, Los Angeles, Calif., under Act of March 3, 1879. town Building, 401 West Seventh St., Los Angeles, Calif. STAGE SHOW LANDSLIDE STARTING IN HOLLYWOOD 17 THEATRICAL Rie PREMIERE PROJECTS SET GtCKTD ACTS May SAN FRANCISCO, Acknowledging the need Approximately $15,- 1. — for stage support for the will be spent on 000,000 big specials, operators of of new construction the film capital de luxe amusement centers in houses have come back to Northern California with- the prologue and other at- in the next three months, tendant showman ship plans are fol- if present features, to keep up box- lowed. office totals for the big Here are seventeen pro- houses. posed theatres, opera On May 30 the Fox- houses and amusement West Coast Grauman’s centers, some of them al- Chinese will return to the ready nearly un^ler way, lavish prologue method, and others only in the with Sid Grauman again conference stage at the helm for the pre- 1. A Sam Levin house on miere of “Hell’s Angels.” Ocean avenue between Fairfield The new Pantages Theatre, and Lakewood avenues, San Fran- to be jointly operated by the Pan- cisco, at an estimated cost of tages brothers with West Coast, $250,000. Plans are under prepa- will start with elaborate prologue ration for this house. -

Planning & Land Use M.Anagement

DEPARTMENT Of L.TY OF LOS ANGELE~ EXECUTIVE OFFICES CITY PlANNING CALIFORNIA OFFICE OF HISTORIC RESOURCES S. GAll GOLDBERG, AlCP 200 N. SPRING STRm, ROOM 620 DIRECTOR (213) 978-1271 LOS ANGELES, CA 90012·4801 (213)978-1200 VINCENT P. BERTONI, AICP CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION DEPUTY DIRECTOR RICHARD BARRON (213)978-1272 PRESIDENT ROELLA H. LOUIE VICE·PRfSIOfNT JOHN M. DUGAN, AICP DfPU1Y DIRECTOR GLEN C. DAKE ANTONIO R. VILLARAIGOSA (213) 978-1274 MIA M. LEHRER MAYOR OZ SCOTT EVA YUAN-McDANIEl DEPUTY DIRECl'OR LOURDES SANCHEZ (213) 978-1273 COMMISSION EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT (213) 978-1300 FAX: (213) 978·1275 INFORMATION (213) 978-1270 wwv-~.ladty.org!PLN November 13, 2008 Los Angeles City Council Room 395, City Hall 200 North Spring Street Los Angeles, California 90012 ATTENTION: Barbara Greaves, Legislative Assistant Planning and Land Use Management Committee CASE NUMBER: CHC-2008-3554-HCM HEERMAN ESTATE 525 SOUTH VAN NESS AVENUE At the Cultural Heritage Commission meeting of October 30, 2008, the Commission moved to include the above property in the list of Historic-Cultural Monuments, subject to adoption by the City Council. As required under the provisions of Section 22.171.10 of the Los Angeles Administrative Code, the Commission has solicited opinions and information from the office of the Council District in which the site is located and from any Department or Bureau of the city whose operations may be affected by the designation of such site as a Historic-Cultural Monument. Such designation in and of itself has no fiscal impact. Future applications for permits may cause minimal administrative costs. -

Columbia Pictures: Portrait of a Studio

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Film and Media Studies Arts and Humanities 1992 Columbia Pictures: Portrait of a Studio Bernard F. Dick Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Dick, Bernard F., "Columbia Pictures: Portrait of a Studio" (1992). Film and Media Studies. 8. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_film_and_media_studies/8 COLUMBIA PICTURES This page intentionally left blank COLUMBIA PICTURES Portrait of a Studio BERNARD F. DICK Editor THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Copyright © 1992 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2010 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Cataloging-in-Publication Data for the hardcover edition is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 978-0-8131-3019-4 (pbk: alk. paper) This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the HEERMAN ESTATE

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC -2008 -3554 -HCM HEARING DATE: October 30, 2008 Location: 525 S. Van Ness Avenue TIME: 10:00 AM Council District: 4 PLACE : City Hall, Room 350 Community Plan Area: Wilshire 200 N. Spring Street Area Planning Commission: Central Los Angeles, CA Neighborhood Council: Greater Wilshire 90012 Legal Description: Lot 77 of MB 8-76, Henry J. Brown’s Wilshire Terrace PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the HEERMAN ESTATE REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument APPLICANT: Concerned Residents of Larchmont 140 S. Avenue 57 Los Angeles, CA 90042 OWNER: Ho Y and Woo J. Im 28 Viewpoint Place Laguna Niguel, CA 92677 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.7 2. Adopt the report findings. S. GAIL GOLDBERG, AICP Director of Planning [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Office of Historic Resources Prepared by: [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] ________________________ Edgar Garcia, Preservation Planner Office of Historic Resources Attachments: July 28, 2008 Historic-Cultural Monument Application 525 S. Van Ness Ave. CHC-2008-3554-HCM Page 2 of 4 FINDINGS 1. The building “embodies the distinguishing characteristics of an architectural type specimen, inherently valuable for a study of a period style or method of construction” as an example of Colonial Revival residential architecture. 2. The building is associated with a master builder, designer, or architect, as a work by the architects Albert R. -

THE BOX OFFICE CHECK-UP of 1935

1 to tell the world!* IN 1936 THE BOX OFFICE CHECK-UP of 1935 An annual produced by the combined editorial and statistical facilities of Motion Picture Herald and Motion Picture Daily devoted to the records and ratings of talent in motion pictures of the year. QUIGLEY PUBLISHING COMPANY THE PUBLIC'S MANDATE by MARTIN QUIGLEY 1 The Box Office Check-Up is intended to disclose guidance upon that single question which in the daily operations of the industry over- shadows all others; namely, the relative box office values of types and kinds of pictures and the personnel of production responsible for them. It is the form-sheet of the industry, depending upon past performances for future guidance. Judging what producers, types of pictures and personalities will do in the future must largely depend upon the record. The Box Office Check-Up is the record. Examination of the record this year and every year must inevitably dis- close much information of both arresting interest and also of genuine im- portance to the progress of the motion picture. It proves some conten- tions and disproves others. It is a source of enlightenment, the clarifying rays of which must be depended upon to light the road ahead. ^ Striking is the essential character of those pictures which month in and month out stand at the head of the list of Box Office Cham- pions. Since August, 1934, the following are among the subjects in this classification: "Treasure Island," "The Barretts of Wimpole Street," "Flirta- tion Walk," "David Copperfield," "Roberta," "Love Me Forever," "Curley -

Cinema's Unstable Texts

Cinema’s Unstable Texts: A Historical Analysis of Textual Variation in the Film Industry By Mikhail L. Skoptsov B.A. New York University, 2010 M.A. University of Southern California, 2012 Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Modern Culture and Media at Brown University Providence, Rhode Island May 2020 © Copyright 2020 by Mikhail Skoptsov This dissertation by Mikhail L. Skoptsov is accepted in its present form by the Department of Modern Culture and Media as satisfying the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date______________ ____________________________ Philip Rosen, Advisor Recommended to the Graduate Council Date______________ ____________________________ Lynne Joyrich, Reader Date______________ ____________________________ Ariella Azoulay, Reader Approved by the Graduate Council Date______________ ____________________________ Andrew G. Campbell, Dean of the Graduate School iii Curriculum Vitae Mikhail Skoptsov graduated in 2010 from New York University with a B.A. in Cinema Studies with honors, a second major in the French language, and a minor in Producing. He subsequently graduated with an M.A. in Film Studies from the University of Southern California (USC) in 2012. His published academic works include a book chapter in Bringing History to Life Through Film: The Art of Cinematic Storytelling (2013), and articles in the online international journal Series (2015) and Contexts (Spring 2018), the official annual publication of the Haffenreffer Museum of Anthropology. A forthcoming book chapter will appear in The Hobbit in Film and Fiction: Essays on Peter Jacksons Hobbit Trilogy (2020). As a former film critic, he has published multiple reviews in Washington Square News and The Daily Trojan newspapers. -

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

TO THE MEMBERS OF THE ACADEMY OF MOTION PICTURE ARTS AND SCIENCES VOL. 3; No. 6-7 9038 MELROSE AVENUE • HOLLYWOOD 46, CALIF. JUNE-JULY, 1947 INTERNATIONAL FILM EXPOSITION PLANNED "IN THE BEGINNING" by HERSHOL T OUTLINES FILM CONGRESS MARY C. MCCALL, JR. IN ADDRESS TO UNITED NATIONS CLUB It is the plan of the Academy to. A film congress, the first of its kind to be held in this country; devote an issue of " For You r In is planned for Hollywood. The exposition, for which no definite formation" to each branch of its date has been set, will include leading artists and craftsmen in the membership until all the Academy motion picture industry the world over. branches have been covered. jean Hersholt, president of the Academy, made the announce . It is appropriate that the first ment before an audience of fifteen hundred members of fifty-five of this series of informational bulle nations at the United Nations Club in Washington. tins should be devoted to the Writ He stated: ers Branch of the Academy. For it "1 feel that at a gathering such as this, it is appropriate that I is as true in the creation of a mo announce that the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences tion picture as the Bible tells us it will sponsor an International Film Congress in Hollywood a year was in the creation of the world from this summer. We shall bring together from all parts of the that The Word is the Beginning. world men and woman who made this medium one of the great The story·, the play, is the basis of vehicles for the interchange of social and cultural ideas--probably a motion picture.