Aristophanes' Frogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resounding Mysteries: Sound and Silence in the Eleusinian Soundscape

Body bar (print) issn 2057–5823 and bar (online) issn 2057–5831 Religion Article Resounding mysteries: sound and silence in the Eleusinian soundscape Georgia Petridou Abstract The term ‘soundscape’, as coined by the Canadian composer R. Murray Schafer at the end of the 1960s, refers to the part of the acoustic environment that is per- ceivable by humans. This study attempts to reconstruct roughly the Eleusinian ‘soundscape’ (the words and the sounds made and heard, and those others who remained unheard) as participants in the Great Mysteries of the two Goddesses may have perceived it in the Classical and post-Classical periods. Unlike other mystery cults (e.g. the Cult of Cybele and Attis) whose soundscapes have been meticulously investigated, the soundscape of Eleusis has received relatively little attention, since the visual aspect of the Megala Mysteria of Demeter and Kore has for decades monopolised the scholarly attention. This study aims at putting things right on this front, and simultaneously look closely at the relational dynamic of the acoustic segment of Eleusis as it can be surmised from the work of well-known orators and philosophers of the first and second centuries ce. Keywords: Demeter; Eleusis; Kore; mysteries; silence; sound; soundscape Affiliation University of Liverpool, UK. email: [email protected] bar vol 2.1 2018 68–87 doi: https://doi.org/10.1558/bar.36485 ©2018, equinox publishing RESOUNDING MYSTERIES: SOUND AND SILENCE IN THE ELEUSINIAN SOUNDSCAPE 69 Sound, like breath, is experienced as a movement of coming and going, inspiration and expiration. If that is so, then we should say of the body, as it sings, hums, whistles or speaks, that it is ensounded. -

The Frogs 2K4: Showdown in Hades

SCRIPT The Frogs 2K4: Showdown in Hades Directed by Kerri Rambow XANTHIAS: Man, do you think I should say one of those Martin Lawrence lines to entertain these bougie people? I could make them laugh just like the movies. DIONYSUS: Sure. Say anything you want, except of course, something like, "Oh these bags! Oh my back!" And don’t talk about my momma. XANTHIAS: But that’s funny! Don’t you want me to do my job? DIONYSUS: Whatever! Stop using my issues as your lines--"Dionysus’ mom is so old, she farts dust." That’s really not funny. XANTHIAS: Well it’s funny to the audience, and no one else is having any problems with it. DIONYSUS: Oh yeah, did I mention you also can’t say "My blisters! My blisters on my blisters! My blisters in places you don’t want to know. Oh! Oh! Oh! Can’t you at least wait until I’m dead and gone? XANTHIAS: But by then no one would think it was funny. Just this one last time, until I get new lines... DIONYSUS: How about "NO"? If I was there in the audience your jokes would make me grow old. XANTHIAS: Well, this play is supposed to be a comedy. What if I told the joke about the chicken, and the guy with the chicken, and...and he made a chicken with... DIONYSUS: (To audience) That joke is really old. Older than my mother. (To Xanthias) Go on! Tell them! Just don’t...don’t... XANTHIAS: Don’t do what? DIONYSUS: Don’t drop my shoes. -

Interpretation: a Journal of Political Philosophy

Interpretation A JOURNAL A OF POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Spring 1994 Volume 21 Number 3 Aristophanes' Mark Kremer Criticism of Egalitarianism: An Interpretation of The Assembly of Women Steven Forde The Comic Poet, the City, and the Gods: Dionysus' Katabasis in the Frogs of Aristophanes Tucker Landy Virtue, Art, and the Good Life in Plato's Protagoras Nalin Ranasinghe Deceit, Desire, and the Dialectic: Plato's Republic Revisited Olivia Delgado de Torres Reflections on Patriarchy and the Rebellion of Daughters in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice and Othello Alfred Mollin On Hamlet's Mousetrap Joseph Alulis The Education of the Prince in Shakespeare's King Lear David Lowenthal King Lear Glenn W. Olsen John Rawls and the Flight from Authority: The Quest for Equality as an Exercise in Primitivism Book Reviews Will Morrisey The Roots of Political Philosophy: Ten Forgotten Socratic Dialogues, edited by Thomas L. Pangle John C. Koritansky Interpreting Tocqueville s "Democracy in America," edited by Ken Masugi Interpretation Editor-in-Chief Hilail Gildin, Dept. of Philosophy, Queens College Executive Editor Leonard Grey General Editors Seth G. Benardete Charles E. Butterworth Hilail Gildin Robert Horwitz (d. 1987) Howard B. White (d. 1974) Consulting Editors Christopher Bruell Joseph Cropsey Ernest L. Fortin John Hallowell (d. 1992) Harry V. Jaffa David Lowenthal Muhsin Mahdi Harvey C. Mansfield, Jr. Arnaldo Momigliano (d. 1987) Michael Oakeshott (d. 1990) Ellis Sandoz Leo Strauss (d. 1973) Kenneth W. Thompson European Editors Terence E. Marshall Heinrich Meier Editors Wayne Ambler Maurice Auerbach Fred Baumann Michael Blaustein Patrick Coby Edward J. Erler Maureen Feder-Marcus Joseph E. Goldberg Stephen Harvey Pamela K. -

ARISTOPHANES' FROGS 172 F. by CW DEARDEN the Problem

WHAT HAPPENED TO THE DONKEY? ARISTOPHANES' FROGS 172 f. BY C. W. DEARDEN The problem of the production of Charon's boat 1) is one of the perennial chestnuts of Aristophanic study, yet one that theore- tically it ought to be fairly easy to solve, for, as Arnott has remark- ed 2), the movements of the characters in the early scenes of the Frogs can be plotted with considerable accuracy and this limits in certain respects the possibilities open to the producer. Dionysus and Xanthias open the play as with donkey and baggage they appear on their way to visit Heracles and then the Underworld. The conclusion that they enter through a parodos and journey across the orchestra seems unavoidable for no starting point is indicated for their journey and the donkey would pose problems elsewhere. At line 35 therefore, when Xanthias dismounts, the two climb onto the stage and approach Heracles' door. A conversation with Heracles occupies the next 130 lines before the two travellers bid him adieu and turn back to the orchestra to continue their journey. Xanthias bidden once more to pick up the baggage, pro- duces his customary complaint, suggests that Dionysus might consider hiring a corpse to take the luggage to Hades (167) and points out that one is being carried in. There is no indication of where the corpse comes from and again it seems reasonable to assume that it is simply carried in through one parodos across the orchestra and out through the other; Dionysus and Xanthias them- 1) For the purposes of this article the conclusions of T.B.L. -

Determining Stephen Sondheim's

“I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS BY ©2011 PETER CHARLES LANDIS PURIN Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy ___________________________ Dr. Deron McGee ___________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ___________________________ Dr. John Staniunas ___________________________ Dr. William Everett Date Defended: August 29, 2011 ii The Dissertation Committee for PETER PURIN Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy Date approved: August 29, 2011 iii Abstract This dissertation offers a music-theoretic analysis of the musical style of Stephen Sondheim, as surveyed through his fourteen musicals that have appeared on Broadway. The analysis begins with dramatic concerns, where musico-dramatic intensity analysis graphs show the relationship between music and drama, and how one may affect the interpretation of events in the other. These graphs also show hierarchical recursion in both music and drama. The focus of the analysis then switches to how Sondheim uses traditional accompaniment schemata, but also stretches the schemata into patterns that are distinctly of his voice; particularly in the use of the waltz in four, developing accompaniment, and emerging meter. Sondheim shows his harmonic voice in how he juxtaposes treble and bass lines, creating diagonal dissonances. -

The Frogs: a Modern Adaptation Comedy by Don Zolidis

The Frogs: A Modern Adaptation Comedy by Don Zolidis © Dramatic Publishing Company The Frogs: A Modern Adaptation Comedy by Don Zolidis. Cast: 6 to 25m., 6 to 25w., 8 to 40 either gender. Disgusted with the state of current entertainment, Dionysus, God of Wine and Poetry, decides that it’s time to retrieve Shakespeare from the underworld. Surely if the Bard were given a series on HBO, he’d be able to raise the level of discourse! Accompanied by his trusted servant, Xanthias (the brains of the operation), Dionysus seeks help from Hercules and Charon the Boatman. Unfortunately, his plan to rescue Shakespeare goes horribly awry, as he’s captured by a chorus of reality-television-loving demon frogs. The frogs put the god on trial and threaten him with never-ending torment unless he brings more reality shows into the world. It won’t be easy for Dionysus to survive, and, even if he does get past the frogs, Jane Austen isn’t ready to let Shakespeare escape without a fight. Adapted from Aristophanes’ classic satire, The Frogs is a hilarious and scathing look at highbrow and lowbrow art. Flexible staging. Approximate running time: 100 minutes. Code: FF5. Cover design: Molly Germanotta. ISBN: 978-1-61959-067-0 Dramatic Publishing Your Source for Plays and Musicals Since 1885 311 Washington Street Woodstock, IL 60098 www.dramaticpublishing.com 800-448-7469 © Dramatic Publishing Company The Frogs: A Modern Adaptation By DON ZOLIDIS Dramatic Publishing Company Woodstock, Illinois ● Australia ● New Zealand ● South Africa © Dramatic Publishing Company *** NOTICE *** The amateur and stock acting rights to this work are controlled exclusively by THE DRAMATIC PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC., without whose permission in writing no performance of it may be given. -

THE SKYLARK and the FROGS Your First Example of Dystopian Writing…Enjoy!

THE SKYLARK AND THE FROGS Your first example of dystopian writing…enjoy! There was once a society of frogs that lived at the bottom of a deep, dark well, from which nothing whatsoever could be seen of the world outside. They were ruled over by a great Boss Frog, a fearful bully who claimed, on rather dubious grounds, to own the well and all that creeped or crawled therein. The Boss Frog never did a lick of work to feed or keep himself, but lived off the labors of the several bottom-dog frogs with whom he shared the well. They, wretched creatures, spent all the hours of their lightless days and a good many more of their lightless nights drudging about in the damp and slime to find the tiny grubs and mites on which the Boss Frog fattened. Now, occasionally an eccentric skylark would flutter down into the well and would sing to the frogs of all the marvelous things it had seen in its journeyings in the great world outside: of the sun and the moon and the stars, of the sky-climbing mountains and fruitful valleys and the vast stormy seas, and of what it was like to adventure the boundless space above them. Whenever the skylark came visiting, the Boss Frog would 20 instruct the bottom-dog frogs to attend closely to all the bird had to tell. "For he is telling you," the Boss Frog would explain, "of the happy laud wither all good frogs go for their reward when they finish this life of trials." Secretly, however, the Boss Frog thought this strange bird was quite mad. -

Aristophanes in Performance 421 BC–AD 2007

an offprint from Aristophanes in Performance 421 BC–AD 2007 Peace, Birds and Frogs ❖ EDITED BY EDITH HALL AND AMANDA WRIGLEY Modern Humanities Research Association and Maney Publishing Legenda: Oxford, 2007 C H A P T E R 16 ❖ A Poet without ‘Gravity’: Aristophanes on the Italian Stage Francesca Schironi Since the beginning of the twentieth century, Aristophanes has enjoyed a certain public profile: I have counted at least seventy-four official productions that have taken place in Italy since 1911. The most popular play by far seems to be Birds, which has taken the stage in sixteen different productions. Clouds is also reasonably popular, having been staged in twelve different productions. There have also been some interesting rewritings and pastiches of more than one play. But particularly striking is the relative infrequency with which Frogs — in my view one of Aristophanes’ most engaging comedies — has been produced: it has only seen public performance twice, in 1976 and in 2002.1 Indeed, it is one of those two productions of Frogs that attracted my attention: the most recent one, directed by Luca Ronconi at Syracuse in May 2002. As most people know by now, this performance excited many discussions, in Italy,2 as well as abroad,3 because of widespread suspicion that it had incurred censorship at the hands of Berlusconi’s government. I would like to reconsider this episode, not only because it is both striking and ambiguous, but above all because on closer inspection it seems to me a particularly good illustration of how theatre, and in particular ancient Greek and Roman theatre, ‘works’ in Italy. -

Side by Side by Sondheim Jan

Side by Side by Sondheim Jan. 27 – Feb. 19, 2017 at Spencer Theatre Cast & Creative Team Overview About the Artists JENNY ASHMAN (Ensemble) KC Rep: Evita; Off Broadway: Sleep No More; Regional: The Little Mermaid in Concert (The Hollywood Bowl); Evita (Opera North); Sweeney Todd (The Production Company); As You Like It (The Next Stage Theatre); Romance Language (Seven Angels Theatre); Little Women (The Lyric Theatre); A New Brain (Orlando Repertory Theatre); Awards: Nominated for a Los Angeles Ovation Award for Featured Actress in a Musical for Sweeney Todd; Upcoming: Bea Stein in J.D. Salinger biopic, Rebel in the Rye (directed by Empire creator Danny Strong); Education: University of Central Florida Conservatory Theatre - www.jennyashman.com - AEA Member. SHANNA JONES (Ensemble) KC Rep: The Diary of Anne Frank, Sunday in the Park with George, Stillwater, Hair: Retrospection, The Santaland Diaries (2013, 2014, 2015, 2016); New York: Phaedra’s Cabaret, Undone, and Decline and Fall (New York Theatre Workshop); Chicago: Tug of War; Foreign Fire & Civil Strife (Chicago Shakespeare Theatre); Regional: Les Misérables (Pioneer Theatre Company); Romeo and Juliet (Utah Shakespearean Festival); Saturday’s Voyeur (Salt Lake Acting Company); Education: BA, the Actor Training Program at the University of Utah (2008) - www.shannajonesmusic.com - AEA Member. ORVILLE MENDOZA (Ensemble) made his KC Rep debut in the world premiere of A Christmas Story, The Musical directed by Eric Rosen. He is thrilled to be back in Kansas City where he was most recently seen as “The Engineer” in Miss Saigon at Starlight Theatre. Orville is excited to be performing Side by Side by Sondheim having worked with Stephen Sondheim in three of his shows: Pacific Overtures, which was Orville’s Broadway debut; Road Show, directed by John Doyle, original company member and original cast recording (Nonesuch Records); and the 2013 Classic Stage Company revival of Passion, also directed by John Doyle, cast recording (P.S. -

Paul Epstein, Aristophanes on Tragedy

ARISTOPHANES ON TRAGEDY Paul Epstein Oklahoma State University [email protected] Fifty years before Aristotle wrote his Poetics, Aristophanes had devoted two comedies, Thesmophoriazusae (411) and Frogs (405), to the subject of tragedy. In both plays the plot shows the education of the main character in the nature of tragedy. Euripides learns in Thesmophoriazusae that he must present noble and not base women in his dramas. His depiction of perverse women in the theatre had moved real-life husbands to keep a narrow watch on their wives, and in order to be free of this tyranny, the women use their Thesmophoria1 to compel Euripides to change. Frogs shows the education of the god who presides over tragedy: Dionysus discovers that the telos of the tragedy-writer’s art is the education of the spectators to a heroic defence of their country. This discovery reverses the god’s earlier assumption that his own taste could judge the excellence of a poet. For both comedies, tragedy is a theoretical activity with direct practical results; what the spectators see in the theatre will determine their activity in the family or the State. 2 These ‘statements’ about tragedy occur through an argument whose general form 1 This is an Athenian festival which celebrated Demeter and Persephone as the Thesmophoroi, a term which B. B. Rogers understands as “the givers and guardians of Home.” [The Thesmophoriazusae of Aristophanes (London: G. Bell and Sons, 1920), pp. x, xi.] Certainly, the drama concentrates on this particular meaning of the Thesmophoroi, even though the festival also marks the annual cycle of death and rebirth that the story of the two goddesses celebrates. -

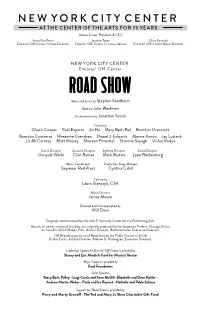

Read the Road Show Program

NEW YORK CITY CENTER AT THE CENTER OF THE ARTS FOR 75 YEARS Arlene Shuler, President & CEO Anne Kauffman Jeanine Tesori Chris Fenwick Encores! Off-Center Artistic Director Encores! Off-Center Creative Advisor Encores! Off-Center Music Director NEW YORK CITY CENTER Encores! Off-Center Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by John Weidman Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Featuring Chuck Cooper Raúl Esparza Jin Ha Mary Beth Peil Brandon Uranowitz Brandon Contreras Rheaume Crenshaw Daniel J. Edwards Marina Kondo Jay Lusteck Liz McCartney Matt Moisey Shereen Pimentel Sharone Sayegh Vishal Vaidya Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Donyale Werle Clint Ramos Mark Barton Leon Rothenberg Music Coordinator Production Stage Manager Seymour Red Press Cynthia Cahill Casting by Laura Stanczyk, CSA Music Director James Moore Directed and Choreographed by Will Davis Originally commissioned by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Bounce, an earlier version of this play, was originally produced by the Goodman Theatre, Chicago, Illinois on June 30, 2003 (Robert Falls, Artistic Director; Roche Schulfer, Executive Director). Off-Broadway premiere of Road Show by the Public Theater in 2008 (Oskar Eustis, Artistic Director; Andrew D. Hamingson, Executive Director). Leadership Support for Encores! Off-Center is provided by Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater Major Support is provided by Ford Foundation Series Sponsors Stacy Bash-Polley • Luigi Caiola and Sean McGill • Elizabeth and Dean Kehler • -

A BED and a CHAIR: a New York Love Affair

Contact: Helene Davis [email protected]/212.354.7436 Helene Davis Public Relations: NORM LEWIS, JEREMY JORDAN join CYRILLE AIMÉE, BERNADETTE PETERS in A BED AND A CHAIR: A New York Love Affair New Stephen Sondheim/Wynton Marsalis Collaboration Presented by NEW YORK CITY CENTER & JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER Directed by John Doyle; Choreographed by Parker Esse November 13 – 17 at City Center Special Gala Benefit Performance on November 14 New York, N.Y., October 11, 2013 – Norm Lewis and Jeremy Jordan will join Cyrille Aimée and Bernadette Peters in Stephen Sondheim and Wynton Marsalis’s A BED AND A CHAIR: A New York Love Affair, a new musical event featuring Sondheim’s music arranged and performed by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis. This Encores! Special Event, directed by frequent Sondheim collaborator John Doyle, with choreography by Parker Esse and musical supervision by David Loud, was conceived by Peter Gethers, Jack Viertel and John Doyle, and will run for seven performances, November 13 – 17 at City Center. The cast will include Cyrille Aimée, Jeremy Jordan, Norm Lewis and Bernadette Peters with dancers Meg Gillentine, Tyler Hanes, Grasan Kingsberry and Elizabeth Parkinson. A BED AND A CHAIR: A New York Love Affair, presented by the combined forces of City Center’s Encores! program and Jazz at Lincoln Center, celebrates love in New York and love of New York. Native Manhattanite Sondheim and adopted citizen Marsalis (originally from New Orleans) and compared musical notes on their shared passion for our city in a program that features more than two dozen Sondheim compositions, each piece newly re-imagined by the unique musical sensibility of Marsalis and performed by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra.