THE SKYLARK and the FROGS Your First Example of Dystopian Writing…Enjoy!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interpretation: a Journal of Political Philosophy

Interpretation A JOURNAL A OF POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY Spring 1994 Volume 21 Number 3 Aristophanes' Mark Kremer Criticism of Egalitarianism: An Interpretation of The Assembly of Women Steven Forde The Comic Poet, the City, and the Gods: Dionysus' Katabasis in the Frogs of Aristophanes Tucker Landy Virtue, Art, and the Good Life in Plato's Protagoras Nalin Ranasinghe Deceit, Desire, and the Dialectic: Plato's Republic Revisited Olivia Delgado de Torres Reflections on Patriarchy and the Rebellion of Daughters in Shakespeare's Merchant of Venice and Othello Alfred Mollin On Hamlet's Mousetrap Joseph Alulis The Education of the Prince in Shakespeare's King Lear David Lowenthal King Lear Glenn W. Olsen John Rawls and the Flight from Authority: The Quest for Equality as an Exercise in Primitivism Book Reviews Will Morrisey The Roots of Political Philosophy: Ten Forgotten Socratic Dialogues, edited by Thomas L. Pangle John C. Koritansky Interpreting Tocqueville s "Democracy in America," edited by Ken Masugi Interpretation Editor-in-Chief Hilail Gildin, Dept. of Philosophy, Queens College Executive Editor Leonard Grey General Editors Seth G. Benardete Charles E. Butterworth Hilail Gildin Robert Horwitz (d. 1987) Howard B. White (d. 1974) Consulting Editors Christopher Bruell Joseph Cropsey Ernest L. Fortin John Hallowell (d. 1992) Harry V. Jaffa David Lowenthal Muhsin Mahdi Harvey C. Mansfield, Jr. Arnaldo Momigliano (d. 1987) Michael Oakeshott (d. 1990) Ellis Sandoz Leo Strauss (d. 1973) Kenneth W. Thompson European Editors Terence E. Marshall Heinrich Meier Editors Wayne Ambler Maurice Auerbach Fred Baumann Michael Blaustein Patrick Coby Edward J. Erler Maureen Feder-Marcus Joseph E. Goldberg Stephen Harvey Pamela K. -

Determining Stephen Sondheim's

“I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS BY ©2011 PETER CHARLES LANDIS PURIN Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy ___________________________ Dr. Deron McGee ___________________________ Dr. Paul Laird ___________________________ Dr. John Staniunas ___________________________ Dr. William Everett Date Defended: August 29, 2011 ii The Dissertation Committee for PETER PURIN Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: “I’VE A VOICE, I’VE A VOICE”: DETERMINING STEPHEN SONDHEIM’S COMPOSITIONAL STYLE THROUGH A MUSIC-THEORETIC ANALYSIS OF HIS THEATER WORKS ___________________________ Chairperson Dr. Scott Murphy Date approved: August 29, 2011 iii Abstract This dissertation offers a music-theoretic analysis of the musical style of Stephen Sondheim, as surveyed through his fourteen musicals that have appeared on Broadway. The analysis begins with dramatic concerns, where musico-dramatic intensity analysis graphs show the relationship between music and drama, and how one may affect the interpretation of events in the other. These graphs also show hierarchical recursion in both music and drama. The focus of the analysis then switches to how Sondheim uses traditional accompaniment schemata, but also stretches the schemata into patterns that are distinctly of his voice; particularly in the use of the waltz in four, developing accompaniment, and emerging meter. Sondheim shows his harmonic voice in how he juxtaposes treble and bass lines, creating diagonal dissonances. -

The Frogs: a Modern Adaptation Comedy by Don Zolidis

The Frogs: A Modern Adaptation Comedy by Don Zolidis © Dramatic Publishing Company The Frogs: A Modern Adaptation Comedy by Don Zolidis. Cast: 6 to 25m., 6 to 25w., 8 to 40 either gender. Disgusted with the state of current entertainment, Dionysus, God of Wine and Poetry, decides that it’s time to retrieve Shakespeare from the underworld. Surely if the Bard were given a series on HBO, he’d be able to raise the level of discourse! Accompanied by his trusted servant, Xanthias (the brains of the operation), Dionysus seeks help from Hercules and Charon the Boatman. Unfortunately, his plan to rescue Shakespeare goes horribly awry, as he’s captured by a chorus of reality-television-loving demon frogs. The frogs put the god on trial and threaten him with never-ending torment unless he brings more reality shows into the world. It won’t be easy for Dionysus to survive, and, even if he does get past the frogs, Jane Austen isn’t ready to let Shakespeare escape without a fight. Adapted from Aristophanes’ classic satire, The Frogs is a hilarious and scathing look at highbrow and lowbrow art. Flexible staging. Approximate running time: 100 minutes. Code: FF5. Cover design: Molly Germanotta. ISBN: 978-1-61959-067-0 Dramatic Publishing Your Source for Plays and Musicals Since 1885 311 Washington Street Woodstock, IL 60098 www.dramaticpublishing.com 800-448-7469 © Dramatic Publishing Company The Frogs: A Modern Adaptation By DON ZOLIDIS Dramatic Publishing Company Woodstock, Illinois ● Australia ● New Zealand ● South Africa © Dramatic Publishing Company *** NOTICE *** The amateur and stock acting rights to this work are controlled exclusively by THE DRAMATIC PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC., without whose permission in writing no performance of it may be given. -

Side by Side by Sondheim Jan

Side by Side by Sondheim Jan. 27 – Feb. 19, 2017 at Spencer Theatre Cast & Creative Team Overview About the Artists JENNY ASHMAN (Ensemble) KC Rep: Evita; Off Broadway: Sleep No More; Regional: The Little Mermaid in Concert (The Hollywood Bowl); Evita (Opera North); Sweeney Todd (The Production Company); As You Like It (The Next Stage Theatre); Romance Language (Seven Angels Theatre); Little Women (The Lyric Theatre); A New Brain (Orlando Repertory Theatre); Awards: Nominated for a Los Angeles Ovation Award for Featured Actress in a Musical for Sweeney Todd; Upcoming: Bea Stein in J.D. Salinger biopic, Rebel in the Rye (directed by Empire creator Danny Strong); Education: University of Central Florida Conservatory Theatre - www.jennyashman.com - AEA Member. SHANNA JONES (Ensemble) KC Rep: The Diary of Anne Frank, Sunday in the Park with George, Stillwater, Hair: Retrospection, The Santaland Diaries (2013, 2014, 2015, 2016); New York: Phaedra’s Cabaret, Undone, and Decline and Fall (New York Theatre Workshop); Chicago: Tug of War; Foreign Fire & Civil Strife (Chicago Shakespeare Theatre); Regional: Les Misérables (Pioneer Theatre Company); Romeo and Juliet (Utah Shakespearean Festival); Saturday’s Voyeur (Salt Lake Acting Company); Education: BA, the Actor Training Program at the University of Utah (2008) - www.shannajonesmusic.com - AEA Member. ORVILLE MENDOZA (Ensemble) made his KC Rep debut in the world premiere of A Christmas Story, The Musical directed by Eric Rosen. He is thrilled to be back in Kansas City where he was most recently seen as “The Engineer” in Miss Saigon at Starlight Theatre. Orville is excited to be performing Side by Side by Sondheim having worked with Stephen Sondheim in three of his shows: Pacific Overtures, which was Orville’s Broadway debut; Road Show, directed by John Doyle, original company member and original cast recording (Nonesuch Records); and the 2013 Classic Stage Company revival of Passion, also directed by John Doyle, cast recording (P.S. -

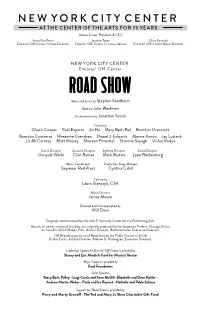

Read the Road Show Program

NEW YORK CITY CENTER AT THE CENTER OF THE ARTS FOR 75 YEARS Arlene Shuler, President & CEO Anne Kauffman Jeanine Tesori Chris Fenwick Encores! Off-Center Artistic Director Encores! Off-Center Creative Advisor Encores! Off-Center Music Director NEW YORK CITY CENTER Encores! Off-Center Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by John Weidman Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Featuring Chuck Cooper Raúl Esparza Jin Ha Mary Beth Peil Brandon Uranowitz Brandon Contreras Rheaume Crenshaw Daniel J. Edwards Marina Kondo Jay Lusteck Liz McCartney Matt Moisey Shereen Pimentel Sharone Sayegh Vishal Vaidya Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Donyale Werle Clint Ramos Mark Barton Leon Rothenberg Music Coordinator Production Stage Manager Seymour Red Press Cynthia Cahill Casting by Laura Stanczyk, CSA Music Director James Moore Directed and Choreographed by Will Davis Originally commissioned by the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Bounce, an earlier version of this play, was originally produced by the Goodman Theatre, Chicago, Illinois on June 30, 2003 (Robert Falls, Artistic Director; Roche Schulfer, Executive Director). Off-Broadway premiere of Road Show by the Public Theater in 2008 (Oskar Eustis, Artistic Director; Andrew D. Hamingson, Executive Director). Leadership Support for Encores! Off-Center is provided by Stacey and Eric Mindich Fund for Musical Theater Major Support is provided by Ford Foundation Series Sponsors Stacy Bash-Polley • Luigi Caiola and Sean McGill • Elizabeth and Dean Kehler • -

A BED and a CHAIR: a New York Love Affair

Contact: Helene Davis [email protected]/212.354.7436 Helene Davis Public Relations: NORM LEWIS, JEREMY JORDAN join CYRILLE AIMÉE, BERNADETTE PETERS in A BED AND A CHAIR: A New York Love Affair New Stephen Sondheim/Wynton Marsalis Collaboration Presented by NEW YORK CITY CENTER & JAZZ AT LINCOLN CENTER Directed by John Doyle; Choreographed by Parker Esse November 13 – 17 at City Center Special Gala Benefit Performance on November 14 New York, N.Y., October 11, 2013 – Norm Lewis and Jeremy Jordan will join Cyrille Aimée and Bernadette Peters in Stephen Sondheim and Wynton Marsalis’s A BED AND A CHAIR: A New York Love Affair, a new musical event featuring Sondheim’s music arranged and performed by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton Marsalis. This Encores! Special Event, directed by frequent Sondheim collaborator John Doyle, with choreography by Parker Esse and musical supervision by David Loud, was conceived by Peter Gethers, Jack Viertel and John Doyle, and will run for seven performances, November 13 – 17 at City Center. The cast will include Cyrille Aimée, Jeremy Jordan, Norm Lewis and Bernadette Peters with dancers Meg Gillentine, Tyler Hanes, Grasan Kingsberry and Elizabeth Parkinson. A BED AND A CHAIR: A New York Love Affair, presented by the combined forces of City Center’s Encores! program and Jazz at Lincoln Center, celebrates love in New York and love of New York. Native Manhattanite Sondheim and adopted citizen Marsalis (originally from New Orleans) and compared musical notes on their shared passion for our city in a program that features more than two dozen Sondheim compositions, each piece newly re-imagined by the unique musical sensibility of Marsalis and performed by the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. -

SWEENEY TODD Is Presented Through Special Arrangement with Musical Theatre International (MTI)

July 22-August 7, 2021 Music and Lyrics by Book by Stephen Sondheim Hugh Wheeler From an Adaptation by CHRISTOPHER BOND Originally Directed On Broadway by HAROLD PRINCE Orchestrations by Jonathan Tunick Scenic Designer Costume Designer Lighting Designer Sound Designer Diggle† Sarita P Fellows† Marika Kent Sun Hee Kil† Music Director Choreographer Casting Director Simone Allen Ben Hobbs Michael Cassera Production Stage Manager Production Manager Assistant Musical Director Amanda Spooner* Adam Zonder Megan Smythe Assistant Directors/Dramaturgs Deck Stage Manager/ Dialect Coach/ Fight Captain Intimacy Consultant Kate Semmens~, Arianna Tilley~ Vicki Whooper* Robin Christian McNair * Directed by Member of the Actors' Equity Association, Sanaz Ghajar the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Originally Produced on Broadway by Richard Barr, Charles Woodward, Robert Fryer, Mary Lea Johnson, Martin Richards in Association with Dean and Judy Manos † USA - Member of United Scenic Artists Local 829 SWEENEY TODD Is presented through special arrangement with Musical Theatre International (MTI). ‡ Member of the Hangar Theatre All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. Company Design Fellows www.mtishows.com ~ Member of the Hangar Theatre Any video and/or audio recording of this production is strictly prohibited. 2021 Lab Company Premier Performance Sponsor Mainstage Media Sponsor Partner In The Arts Partner In Health CAST Sweeney Todd.............................................................................................................................................................Nik -

A Musical Based on the Play by Aristophanes with Music by Stephen Sondheim

Directorial Proposal for The Frogs A musical based on the play by Aristophanes with music by Stephen Sondheim It's The Producers meets Ancient Greece! A rarely staged show with wonderful, memorable music by Sondheim and Shevelove. It's a perfect mixture of political satire, theatrical humor, farce, and drama! Both visually and emotionally electric, it is a piece much needed in our politically charged times. Plot of The Frogs: The Frogs opens with two actors debating which play they should perform. They pray to the gods for guidance whilst 'assisting' the audience with a few dos and don'ts - mostly don'ts - during the performance (Invocation and Instructions to the Audience). The two actors reveal themselves to be Dionysus, the god of wine and theatre, and his slave Xanthias, stating that they are on a mission to save the world by bringing back a great playwright from Hades, George Bernard Shaw. They devise a plan to disguise themselves in order to cross the river Styx to rescue the playwright, and set off on their adventure (I Love To Travel). Dionysus visits the one hero he knows who has successfully traveled to and from Hades, the half god Herakles, who gives the two tips on how to sneak into the underworld (Dress Big). After trying on a few lion skins and being given a large club, they are set on their way to the River Styx with a warning to be careful of the frogs within the river who like things just the way they are. They finally meet Charon, the ferryman of the underworld, in his skiff ready to take our duo to Hades (All Aboard). -

Musicals by Sondheim – a Full List of His Major Works

Musicals by Sondheim – A Full List of His Major Works Stephen Sondheim is a legend in the theatre world. Not only has he achieved the Tony Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Theatre, he has also received eight Grammys, a Pulitzer Prize, an Olivier Award, and a Presidential Medal of Freedom. Sondheim is so revered, and his music so musically intricate, he is the most complex writer in all of musical theater. Here is a list of the classic and ground-breaking musicals by Sondheim, sorted chronologically. Feel free to listen and research as you will! Saturday Night (1954) Music and Lyrics: Stephen Sondheim Book: Julius and Philip Epstein Although Saturday Night was written in 1954, it wasn’t produced until 1997. It’s one of the lesser known musicals by Sondheim, and it tells the story of Brooklyn bachelors in search of love. Cast Recording | Sheet Music | License West Side Story (1957) Music: Leonard Bernstein Lyrics: Stephen Sondheim Book: Arthur Laurents Inspired by Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, West Side Story follows the developing romance between two young lovers from very different (and rivaling) backgrounds. Cast Recording | Sheet Music | License Gypsy (1959) Music: Jule Styne Lyrics: Stephen Sondheim Book: Arthur Laurents Gypsy tells the story of an eager stage mother who is determined to land fame and success for her daughter while secretly hoping for some fame of her own. Cast Recording | Sheet Music | License A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962) Music and Lyrics: Stephen Sondheim Book: Burt Shevelove and Larry Gelbart Set in ancient Rome, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum follows a slave named Pseudolus, who attempts to obtain freedom by getting involved in his master’s love life. -

Laughter in Aristophanes' Frogs and Shakespeare's As You Like It

Orient Research Journal of Social Sciences ISSN Print 2616-7085 June 2020, Vol.5, No. 1 [22-31] ISSN Online 2616-7093 Laughter in Aristophanes’ Frogs and Shakespeare’s as You like It: A Comparative Analysis Naila Arshad1, Muhammad Shahbaz 2 Samana Khalid 3 1. Professor, Department of English, GC Women University Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan 2. Assistant Professor, Department of English, GC Women University Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan 3. Lecturer, Department of English, GC Women University, Sialkot, Punjab, Pakistan Abstract This research paper is an attempt to highlight the importance and usefulness of laughter evoked by the comedy works in literature. This paper intends to explore how comedy has been the best tool to elicit laughter by presenting comparative study of Greek playwright Aristophanes’ Frogs and Elizabethan playwright Shakespeare’s As You Like It, focusing mainly on the comic diction, different techniques, humorous situations and events and role-playing by the memorable characters to provide pleasure and entertainment. By eliciting similarities and differences in the two plays, we have pointed out the role of literary texts in crossing time and spatial boundaries for amusing humanity through words and actions of their characters. After careful perusal of two comedies from different ages, this study has reflected that a literary artist has the power to heal and can teach humanity how to laugh in varied situations and contexts. Key Words: Laughter, Wit, Humorous, Role-Playing, Pleasure, Entertainment, Humanity Introduction According to Maurice Charney, laughter creating through comedy offers the audience, spectators and readers the opportunity to get mental comfort in recreational atmosphere; to express their emotions through laughter caused by comic diction, inversion of the routine order of things, clowny actions and humorously embarrassing events; to defeat their inner sadness by enjoying the comedy works of great writers of the past like Aristophanes, the pioneer of Greek comedy plays and Shakespeare, the pre-eminent Elizabethan playwright. -

Assassins Study Guide

Civil War Study Guide.qxd 9/13/01 10:31 AM Page 3 MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL MUSIC THEATRE INTERNATIONAL is one of the world’s major dramatic licensing agencies, specializing in Broadway, Off-Broadway and West End musicals. Since its founding in 1952, MTI has been responsible for supplying scripts and musical materials to theatres worldwide and for protecting the rights and legacy of the authors whom it represents. It has been a driving force in cultivating new work and in extending the production life of some of the classics: Guys and Dolls, West Side Story, Fiddler On The Roof, Les Misérables, Annie, Of Thee I Sing, Ain’t Misbehavin’, Damn Yankees, The Music Man, Evita, and the complete musical theatre works of composer/lyricist Stephen Sondheim, among others. Apart from the major Broadway and Off- Broadway shows, MTI is proud to represent youth shows, revues and musicals which began life in regional theatres and have since become worthy additions to the musical theatre canon. MTI shows have been performed by 30,000 amateur and professional theatrical organizations throughout the U.S. and Canada, and in over 60 countries around the world. Whether it’s at a high school in Kansas, by an all-female troupe in Japan or the first production of West Side Story ever staged in Estonia, productions of MTI musicals involve over 10 million people each year. Although we value all our clients, the twelve thousand high schools who perform our shows are of particular importance, for it is at these schools that music and drama educators work to keep theatre alive in their community. -

[email protected] NATHAN LANE TO

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATE November 27, 2012 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] NATHAN LANE TO HOST SYMPHONIC SONDHEIM WITH NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC In His Philharmonic Debut Evening of Music by Celebrated Broadway Composer-Lyricist Stephen Sondheim Paul Gemignani To Conduct January 29, 2013 Nathan Lane — Tony Award–winning star of theater, film, and television — will host Symphonic Sondheim, the New York Philharmonic’s performance of symphonic suites by Pulitzer Prize, Tony Award, Academy Award, and Grammy Award–winning composer Stephen Sondheim on January 29, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. Paul Gemignani will conduct the Orchestra in a program that includes a newly commissioned arrangement from Sunday in the Park with George and orchestral selections from The Enclave, Pacific Overtures, Stavisky, Into the Woods, and Sweeney Todd. Mr. Sondheim is renowned as both a lyricist and composer, and the program spotlights his musical achievements by presenting symphonic suites of his music without his lyrics. Mr. Sondheim studied music at Williams College, and after graduating he earned a two-year grant to study with composer and music theorist Milton Babbitt. Mr. Sondheim credits Babbitt with teaching him “long-line” composition, developing musical ideas over an extended period, and cites Rachmaninoff and Ravel as influences. The New York Philharmonic has presented Stephen Sondheim’s works 68 times, including the critically acclaimed, semi-staged production of Company in April 2011 conducted by Paul Gemignani and featuring Stephen Colbert, Neil Patrick Harris, Christina Hendricks, and Patti LuPone, among others. Making his Philharmonic debut in this program, Nathan Lane starred in Mr.