In the San Francisco Bay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alameda, a Geographical History, by Imelda Merlin

Alameda A Geographical History by Imelda Merlin Friends of the Alameda Free Library Alameda Museum Alameda, California 1 Copyright, 1977 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 77-73071 Cover picture: Fernside Oaks, Cohen Estate, ca. 1900. 2 FOREWORD My initial purpose in writing this book was to satisfy a partial requirement for a Master’s Degree in Geography from the University of California in Berkeley. But, fortunate is the student who enjoys the subject of his research. This slim volume is essentially the original manuscript, except for minor changes in the interest of greater accuracy, which was approved in 1964 by Drs. James Parsons, Gunther Barth and the late Carl Sauer. That it is being published now, perhaps as a response to a new awareness of and interest in our past, is due to the efforts of the “Friends of the Alameda Free Library” who have made a project of getting my thesis into print. I wish to thank the members of this organization and all others, whose continued interest and perseverance have made this publication possible. Imelda Merlin April, 1977 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to acknowledge her indebtedness to the many individuals and institutions who gave substantial assistance in assembling much of the material treated in this thesis. Particular thanks are due to Dr. Clarence J. Glacken for suggesting the topic. The writer also greatly appreciates the interest and support rendered by the staff of the Alameda Free Library, especially Mrs. Hendrine Kleinjan, reference librarian, and Mrs. Myrtle Richards, curator of the Alameda Historical Society. The Engineers’ and other departments at the Alameda City Hall supplied valuable maps an information on the historical development of the city. -

Foster City, a Planned Community in the San Francisco Bay Area

FOS T ER CI T Y - A NEW CI T Y ON T HE BAY A TRIBU T E T O PROFESSOR MI C HAEL MCDOUGALL KAL V IN PLATT As a tribute to Michael McDougall, long-time friend and colleague, Kalvin Platt revisits the Kalvin Platt, FAIA, is project for Foster City, a planned community in the San Francisco Bay Area. Mike was a Chairman of the SWA Group, an International principal planner and designer of this successful story of a new community which, as early Planning and Landscape as 1958, pioneered several planning and urban design maxims that we value today in good Architectural consulting place-making and sustainability. Foster City is a lesson for all of us. firm with 7 offices and award winning projects around the world. Mr. Platt has In the early 1960s; when I came to California as a planner and joined Wilsey, Ham, and Blair, an extensive experience Engineering and Planning Company in Millbrae; I met Michael McDougall. He was working on Foster in Planning New Towns and Communities, City, a new town along the San Francisco Bay. The sinuous “Venice-like” lagoon system that formed Sustainable Land the backbone of the plan amazed me with its inherent beauty and appropriateness to the natural Planning, Urban sloughs that ran along the Bay. What also amazed me was that this was a Master Planned New Design and Park and Town, the first significant effort of this post-WWII large scale planning concept in California and it had Conservation Planning. begun to be built as planned. -

BAYLANDS & CREEKS South San Francisco

Oak_Mus_Baylands_SideA_6_7_05.pdf 6/14/2005 11:52:36 AM M12 M10 M27 M10A 121°00'00" M28 R1 For adjoining area see Creek & Watershed Map of Fremont & Vicinity 37°30' 37°30' 1 1- Dumbarton Pt. M11 - R1 M26 N Fremont e A in rr reek L ( o te C L y alien a o C L g a Agua Fria Creek in u d gu e n e A Green Point M a o N l w - a R2 ry 1 C L r e a M8 e g k u ) M7 n SF2 a R3 e F L Lin in D e M6 e in E L Creek A22 Toroges Slou M1 gh C ine Ravenswood L Slough M5 Open Space e ra Preserve lb A Cooley Landing L i A23 Coyote Creek Lagoon n M3 e M2 C M4 e B Palo Alto Lin d Baylands Nature Mu Preserve S East Palo Alto loug A21 h Calaveras Point A19 e B Station A20 Lin C see For adjoining area oy Island ote Sand Point e A Lucy Evans Lin Baylands Nature Creek Interpretive Center Newby Island A9 San Knapp F Map of Milpitas & North San Jose Creek & Watershed ra Hooks Island n Tract c A i l s Palo Alto v A17 q i ui s to Creek Baylands Nature A6 o A14 A15 Preserve h g G u u a o Milpitas l Long Point d a S A10 A18 l u d p Creek l A3N e e i f Creek & Watershed Map of Palo Alto & Vicinity Creek & Watershed Calera y A16 Berryessa a M M n A1 A13 a i h A11 l San Jose / Santa Clara s g la a u o Don Edwards San Francisco Bay rd Water Pollution Control Plant B l h S g Creek d u National Wildlife Refuge o ew lo lo Vi F S Environmental Education Center . -

About WETA Present Future a Plan for Expanded Bay Area Ferry Service

About WETA Maintenance Facility will consolidate Central and South Bay fleet operations, include a fueling facility with emergency fuel The San Francisco Bay Area Water Emergency Transportation storage capacity, and provide an alternative EOC location, Authority (WETA) is a regional public transit agency tasked with thereby significantly expanding WETA’s emergency response operating and expanding ferry service on the San Francisco and recovery capabilities. Bay, and is responsible for coordinating the water transit response to regional emergencies. Future Present WETA is planning for a system that seamlessly connects cities in the greater Bay Area with San Francisco, using Today, WETA operates daily passenger ferry service to the fast, environmentally responsible vessels, with wait times cities of Alameda, Oakland, San Francisco, Vallejo, and South of 15 minutes or less during peak commute hours. WETA’s San Francisco, carr4$)"(*- /#)тѵр million passengers 2035 vision would expand service throughout the Bay Area, annually under the San Francisco Bay Ferry brand. Over the operating 12 services at 16 terminals with a fleet of 44 vessels. last five years, SF Bay Ferry ridership has grown чф percent. In the near term, WETA will launch a Richmond/San Francisco route (201ш) and new service to Treasure Island. Other By the Numbers terminal sites such as Seaplane Lagoon in Alameda, Berkeley, Mission Bay, Redwood City, the South Bay, and the Carquinez *- /#)ǔǹǒ --$ ./-).+*-/0+ Strait are on the not-too-distant horizon. ($''$*)-$ -. /*ǗǕǑ$& .-*.. 0. 4 --4 /# 4 #4ǹ 1 -44 -ǹ A Plan for Expanded Bay Area Ferry Service --4-$ -.#$+ 1 )! --$ . Vallejo #.$)- . /*!' / /2 )ǓǑǒǘ CARQUINEZ STRAIT Ǚǖʞ.$) ǓǑǒǓǹ )ǓǑǓǑǹ Hercules WETA Expansion Targets Richmond Funded Traveling by ferry has become increasingly more popular in • Richmond Berkeley the Bay Area, as the economy continues to improve and the • Treasure Island Partially Funded Pier 41 Treasure Island population grows. -

Sediment Transport in the San Francisco Bay Coastal System: an Overview

Marine Geology 345 (2013) 3–17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/margeo Sediment transport in the San Francisco Bay Coastal System: An overview Patrick L. Barnard a,⁎, David H. Schoellhamer b,c, Bruce E. Jaffe a, Lester J. McKee d a U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center, Santa Cruz, CA, USA b U.S. Geological Survey, California Water Science Center, Sacramento, CA, USA c University of California, Davis, USA d San Francisco Estuary Institute, Richmond, CA, USA article info abstract Article history: The papers in this special issue feature state-of-the-art approaches to understanding the physical processes Received 29 March 2012 related to sediment transport and geomorphology of complex coastal–estuarine systems. Here we focus on Received in revised form 9 April 2013 the San Francisco Bay Coastal System, extending from the lower San Joaquin–Sacramento Delta, through the Accepted 13 April 2013 Bay, and along the adjacent outer Pacific Coast. San Francisco Bay is an urbanized estuary that is impacted by Available online 20 April 2013 numerous anthropogenic activities common to many large estuaries, including a mining legacy, channel dredging, aggregate mining, reservoirs, freshwater diversion, watershed modifications, urban run-off, ship traffic, exotic Keywords: sediment transport species introductions, land reclamation, and wetland restoration. The Golden Gate strait is the sole inlet 9 3 estuaries connecting the Bay to the Pacific Ocean, and serves as the conduit for a tidal flow of ~8 × 10 m /day, in addition circulation to the transport of mud, sand, biogenic material, nutrients, and pollutants. -

Pinolecreeksedimentfinal

Pinole Creek Watershed Sediment Source Assessment January 2005 Prepared by the San Francisco Estuary Institute for USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and Contra Costa Resource Conservation District San Francisco Estuary Institute The Regional Watershed Program was founded in 1998 to assist local and regional environmental management and the public to understand, characterize and manage environmental resources in the watersheds of the Bay Area. Our intent is to help develop a regional picture of watershed condition and downstream effects through a solid foundation of literature review and peer- review, and the application of a range of science methodologies, empirical data collection and interpretation in watersheds around the Bay Area. Over this time period, the Regional Watershed Program has worked with Bay Area local government bodies, universities, government research organizations, Resource Conservation Districts (RCDs) and local community and environmental groups in the Counties of Marin, Sonoma, Napa, Solano, Contra Costa, Alameda, Santa Clara, San Mateo, and San Francisco. We have also fulfilled technical advisory roles for groups doing similar work outside the Bay Area. This report should be referenced as: Pearce, S., McKee, L., and Shonkoff, S., 2005. Pinole Creek Watershed Sediment Source Assessment. A technical report of the Regional Watershed Program, San Francisco Estuary Institute (SFEI), Oakland, California. SFEI Contribution no. 316, 102 pp. ii San Francisco Estuary Institute ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors gratefully -

Goga Wrfr.Pdf

The National Park Service Water Resources Division is responsible for providing water resources management policy and guidelines, planning, technical assistance, training, and operational support to units of the National Park System. Program areas include water rights, water resources planning, regulatory guidance and review, hydrology, water quality, watershed management, watershed studies, and aquatic ecology. Technical Reports The National Park Service disseminates the results of biological, physical, and social research through the Natural Resources Technical Report Series. Natural resources inventories and monitoring activities, scientific literature reviews, bibliographies, and proceedings of technical workshops and conferences are also disseminated through this series. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for use by the National Park Service. Copies of this report are available from the following: National Park Service (970) 225-3500 Water Resources Division 1201 Oak Ridge Drive, Suite 250 Fort Collins, CO 80525 National Park Service (303) 969-2130 Technical Information Center Denver Service Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, CO 80225-0287 Cover photos: Top: Golden Gate Bridge, Don Weeks Middle: Rodeo Lagoon, Joel Wagner Bottom: Crissy Field, Joel Wagner ii CONTENTS Contents, iii List of Figures, iv Executive Summary, 1 Introduction, 7 Water Resources Planning, 9 Location and Demography, 11 Description of Natural Resources, 12 Climate, 12 Physiography, 12 Geology, 13 Soils, 13 -

Surficial Characteristics of the Bay Floor of South San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bays, California by John L Chin1 and H

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Surficial characteristics of the bay floor of South San Francisco, San Pablo, and Suisun Bays, California by John L Chin1 and H. Edward Clifton1 Open-File Report 90-665 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards (or with the North American Stratigraphic Code). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 1 U.S. Geological Survey, Menlo Park, California 94025 1990 INTRODUCTION San Francisco Bay is the largest estuary on the Pacific Coast of the United States. Although the hydrology and biology of the bay have been extensively studied, almost no studies have been conducted on the surficial characteristics and composition of the bay floor, and how physical processes both form and modify it into different morphologies. Rubin and McCulloch (1979) conducted such a study in central San Francisco Bay. This study was designed to study the southern and northern parts of the bay in a manner analogous to that of Rubin and McCulloch (1979). Our reconnaissance investigation characterizes the surficial morphology of the bay floor as revealed by side-scan sonar imaging and high-resolution bathymetry and deduces the general nature of sedimentation, bedload sediment transport directions, and areas of deposition versus erosion. Our results should apply to current issues involving sedimentation, dredging, pollution, and the disposal of dredge spoils in the San Francisco Bay system and the highly developed urban areas that border it. -

Restoring San Francisco Bay

Restoring San Francisco Bay Amy Hutzel Coastal Conservancy Photo credit: Rick Lewis 150 years of urbanization has altered San Francisco Bay (1850) (1998) We have had a massive impact on the Bay over the last century We’ve filled thousands of acres We’ve dumped garbage IMPORTANCE OF TIDAL MARSH • Growing threat: Climate Change Photo credit: Vivian Reed • Build up of sediment and vegetation takes time. • Higher starting elevation means marshes survive sea-level rise for longer. San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority Mission: To raise and allocate resources for the restoration, enhancement, protection, and enjoyment of wetlands and wildlife habitat in the San Francisco Bay and along its shoreline. The San Francisco Bay Restoration Authority was created by Save The Bay and others through 2008 legislation. Its mandate is to propose new public funding mechanisms to voters for Bay marsh restoration; then provide grants to accelerate wetland restoration, flood protection, and public access to Bay. Governing Board comprised of elected officials from each quadrant of the Bay Area; Advisory Committee represents many community interests. It currently has no funding to carry out Photo credit: Vivian Reed its important mission. Clean and Healthy Bay Ballot Measure: Measure AA June 2016 ballot measure to accelerate Bay wetlands restoration $12/parcel/year for 20 years, would generate ~$500 million for restoration projects around the Bay Strong majority of nine-county Bay Area voters are supportive; needs 2/3 support in all nine counties, cumulatively, to pass Examples of Projects Anticipated to be Eligible For Funding: • Eden Landing (Alameda) • Chelsea Wetlands (Contra Costa) • Bel Marin Keys (Marin) • Edgerly Island (Napa) • Yosemite Slough (San Francisco) • Ravenswood Ponds (San Mateo) • Alviso Ponds (Santa Clara) • Benicia Shoreline (Solano) • Skaggs Island (Sonoma) Clean and Healthy Bay Ballot Measure: Measure AA Restoring vital fish, bird and wildlife habitat. -

Portolá Trail and Development of Foster City Our Vision Table of Contents to Discover the Past and Imagine the Future

Winter 2014-2015 LaThe Journal of the SanPeninsula Mateo County Historical Association, Volume xliii, No. 1 Portolá Trail and Development of Foster City Our Vision Table of Contents To discover the past and imagine the future. Is it Time for a Portolá Trail Designation in San Mateo County? ....................... 3 by Paul O. Reimer, P.E. Our Mission Development of Foster City: A Photo Essay .................................................... 15 To enrich, excite and by T. Jack Foster, Jr. educate through understanding, preserving The San Mateo County Historical Association Board of Directors and interpreting the history Paul Barulich, Chairman; Barbara Pierce, Vice Chairwoman; Shawn DeLuna, Secretary; of San Mateo County. Dee Tolles, Treasurer; Thomas Ames; Alpio Barbara; Keith Bautista; Sandra McLellan Behling; John Blake; Elaine Breeze; David Canepa; Tracy De Leuw; Dee Eva; Ted Everett; Accredited Pat Hawkins; Mark Jamison; Peggy Bort Jones; Doug Keyston; John LaTorra; Joan by the American Alliance Levy; Emmet W. MacCorkle; Karen S. McCown; Nick Marikian; Olivia Garcia Martinez; Gene Mullin; Bob Oyster; Patrick Ryan; Paul Shepherd; John Shroyer; Bill Stronck; of Museums. Joseph Welch III; Shawn White and Mitchell P. Postel, President. President’s Advisory Board Albert A. Acena; Arthur H. Bredenbeck; John Clinton; Robert M. Desky; T. Jack Foster, The San Mateo County Jr.; Umang Gupta; Greg Munks; Phill Raiser; Cynthia L. Schreurs and John Schrup. Historical Association Leadership Council operates the San Mateo John C. Adams, Wells Fargo; Jenny Johnson, Franklin Templeton Investments; Barry County History Museum Jolette, San Mateo Credit Union and Paul Shepherd, Cargill. and Archives at the old San Mateo County Courthouse La Peninsula located in Redwood City, Carmen J. -

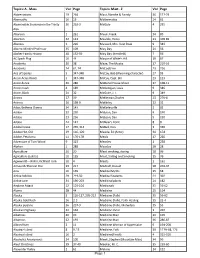

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

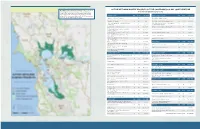

Active Wetland Habitat Projects of the San

ACTIVE WETLAND HABITAT PROJECTS OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY JOINT VENTURE The SFBJV tracks and facilitates habitat protection, restoration, and enhancement projects throughout the nine Bay Area Projects listed Alphabetically by County counties. This map shows where a variety of active wetland habitat projects with identified funding needs are currently ALAMEDA COUNTY MAP ACRES FUND. NEED MARIN COUNTY (continued) MAP ACRES FUND. NEED underway. For a more comprehensive list of all the projects we track, visit: www.sfbayjv.org/projects.php Alameda Creek Fisheries Restoration 1 NA $12,000,000 McInnis Marsh Habitat Restoration 33 180 $17,500,000 Alameda Point Restoration 2 660 TBD Novato Deer Island Tidal Wetlands Restoration 34 194 $7,000,000 Coyote Hills Regional Park - Restoration and Public Prey enhancement for sea ducks - a novel approach 3 306 $12,000,000 35 3.8 $300,000 Access Project to subtidal habitat restoration Hayward Shoreline Habitat Restoration 4 324 $5,000,000 Redwood Creek Restoration at Muir Beach, Phase 5 36 46 $8,200,000 Hoffman Marsh Restoration Project - McLaughlin 5 40 $2,500,000 Spinnaker Marsh Restoration 37 17 $3,000,000 Eastshore State Park Intertidal Habitat Improvement Project - McLaughlin 6 4 $1,000,000 Tennessee Valley Wetlands Restoration 38 5 $600,000 Eastshore State Park Martin Luther King Jr. Regional Shoreline - Water 7 200 $3,000,000 Tiscornia Marsh Restoration 39 16 $1,500,000 Quality Project Oakland Gateway Shoreline - Restoration and 8 200 $12,000,000 Tomales Dunes Wetlands 40 2 $0 Public Access Project Off-shore Bird Habitat Project - McLaughlin 9 1 $1,500,000 NAPA COUNTY MAP ACRES FUND.