Special Feature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lierbergercollege of Fine Arts

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ASU Digital Repository SONIC GEOGRAPHY THE MUSIC OF JOHN LUTHER ADAMS ACME GLENN HACKBARTH, DIRECTOR STUDENT ENSEMBLE RECITAL SERIES KATZIN CONCERT HALL FRIDAY, APRIL 27, 2007 7:30 PM MUSIC lierbergerCollege of Fine Arts ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY Program The Light That Fills the World Sarah Bowlin, violin Christopher Rose, bass Bill Sallak and Matt Coleman, percussion Jennifer Waleczek and Patrick Fanning, synthesizer Eric Schultz, sound ...and bells remembered... Bill Sallak, Jesse Parker, Yi-Chia Chen, Darrell Thompson, Matt Coleman, percussion Eric Schultz, conductor Dark Waves Jennifer Waleczek and Patrick Fanning, piano Eric Schultz, sound **There will be a 10-minute intermission** Dark Wind Josh Bennett, bass clarinet Yi-Chia Chen and Jesse Parker, percussion Patrick Fanning, piano James Smart, conductor Red Arc/Blue Veil Yi-Chia Chen, percussion Jennifer Waleczek, piano Eric Schultz, sound Out of respect for the performers and those audience members around you, please turn all beepers, cell phones and watches to their silent mode. Thank you. ittyRE Performance Events Staff Manager Paul W. Estes Senior Event Mangers: Iftekhar, Anwar, Laura Boone, Edwin Brown, Brady Cullum, Eric Damashek, Mirel DeLaTorre, Anthony Garcia, Ingrid Israel Xian Meng, Kevan Nymeyer Apprentice Event Managers: Lee E. Humphrey, Megan Leigh Smith Events Information Call 480-965-TUNE (480-965-8863) 02006 ASU Herberger College of Fine Arts 0706. -

New Music Festival 2014 1

ILLINOIS STATE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF MUSIC REDNEW MUSIC NOTEFESTIVAL 2014 SUNDAY, MARCH 30TH – THURSDAY, APRIL 3RD CO-DIRECTORS YAO CHEN & CARL SCHIMMEL GUEST COMPOSER LEE HYLA GUEST ENSEMBLES ENSEMBLE DAL NIENTE CONCORDANCE ENSEMBLE RED NOTE New Music Festival 2014 1 CALENDAR OF EVENTS SUNDAY, MARCH 30TH 3 PM, CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Illinois State University Symphony Orchestra and Chamber Orchestra Dr. Glenn Block, conductor Justin Vickers, tenor Christine Hansen, horn Kim Pereira, narrator Music by David Biedenbender, Benjamin Britten, Michael-Thomas Foumai, and Carl Schimmel $10.00 General admission, $8.00 Faculty/Staff, $6.00 Students/Seniors MONDAY, MARCH 31ST 8 PM, KEMP RECITAL HALL Ensemble Dal Niente Music by Lee Hyla (Guest Composer), Raphaël Cendo, Gerard Grisey, and Kaija Saariaho TUESDAY, APRIL 1ST 1 PM, CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS READING SESSION - Ensemble Dal Niente Reading Session for ISU Student Composers 8 PM, KEMP RECITAL HALL Premieres of participants in the RED NOTE New Music Festival Composition Workshop Music by Luciano Leite Barbosa, Jiyoun Chung, Paul Frucht, Ian Gottlieb, Pierce Gradone, Emily Koh, Kaito Nakahori, and Lorenzo Restagno WEDNESDAY, APRIL 2ND 8 PM, KEMP RECITAL HALL Concordance Ensemble Patricia Morehead, guest composer and oboe Music by Midwestern composers Amy Dunker, David Gillingham, Patricia Morehead, James Stephenson, David Vayo, and others THURSDAY, APRIL 3RD 8 PM, KEMP RECITAL HALL ISU Faculty and Students Music by John Luther Adams, Mark Applebaum, Yao Chen, Paul Crabtree, John David Earnest, and Martha Horst as well as the winning piece in the RED NOTE New Music Festival Chamber Composition Competition, Specific Gravity 2.72, by Lansing McLoskey 2 RED NOTE Composition Competition 2014 RED NOTE NEW MUSIC FESTIVAL COMPOSITION COMPETITION CATEGORY A (Chamber Ensemble) There were 355 submissions in this year’s RED NOTE New Music Festival Composition Com- petition - Category A (Chamber Ensemble). -

Swope Bird Program for Web.Pdf

Sacred Music at Notre Dame presents Emily Bird, soprano Jared Swope, baritone MSM Voice Recital “Ego Dormio” from Sacri Affetti SV 300 (1625) Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643) Sonet vox tua in auribus cordis mei Lucrezia Orsina Vizzana (1590–1622) Oiseaux, si tous les ans, K. 307 (1777–78) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Dans un bois solitaire, K. 308 (1777–78) (1756–1791) Quand je fus pris au pavillon (1899) Reynaldo Hahn Rêverie (1895) (1874–1947) Si mes vers avaient des ailes (1895) “Ich wandelte unter den Bäumen” from Liederkreis, Op. 24 (1840) Robert Schumann “Mondnacht” from Liederkreis Op. 39 (1840) (1810–1856) “Aus alten märchen winkt es” from Dichterliebe, Op. 48 (1840) Selections from Vier Gesänge, Op. 70 (1875–77) Johannes Brahms “Im Garten am Seegestade” (1833–1897) “Lerchengesang” “Serenade” “Gratias agimus tibi” from Messe in G-Moll, BWV 235 (c. 1738-39) Johann Sebastian Bach “Quoniam tu solus sanctus” from Messe in B-Moll, BWV 232 (1749) (1685–1750) She’s Like the Swallow (1976) Arr. Benjamin Britten (1913–1976) Sweet Chance, that lead my steps abroad (1914) Michael Head (1900–1976) Sunday, March 24, 2019 7:00PM O’Neill Hall of Music & Sacred Music | LaBar Recital Hall Emily Bird & Jared Swope are students of Prof. Stephen Lancaster. This recital is in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MSM-Voice Performance. Personnel Myles Hayden, Continuo Organ Mona Coalter, Collaborative Pianist SMND Ritornello Ensemble Travon DeLeon, Violin Brook Bennett, Cello Emma Sepmeier, Horn Robert Simon, Bassoon Tiffany Gillaspy, Bassoon Daniel Schwandt, Continuo Organ The piano used in this performance is a gift of David and Shari Boehnen. -

Doctor of Musical Arts in Composition, the Peabody Conservatory

DOUGLAS BUCHANAN, DMA Composer, Conductor, Educator www.dbcomposer.com [email protected] EDUCATION Doctor of Musical Arts in Composition, Peabody Conservatory 2013 • Composition Dissertation: Colonnades, for piano solo, Michael Hersch, advisor • Qualifying Paper: Music and Mythic Meaning: A Ritual Theory of Form and Expression, Dr. Elizabeth Tolbert, advisor Master of Music in Music Theory Pedagogy, Peabody Conservatory 2008 • Qualifying Paper: Course Materials for 20th-Century Ear Training, Dr. Kip Wile, advisor Master of Music in Composition, Peabody Conservatory 2008 • Composition studies with Nicholas Maw and Michael Hersch • Conducting studies with Harlan Parker Bachelor of Music in Piano Performance, summa cum laude, The College of Wooster 2006 • Choral conducting and organ studies with John Russell • Composition studies with Jack Gallagher and Peter Mowrey • Piano studies with Bryan Dykstra and Peter Mowrey • Received Departmental Honors and Pi Kappa Lambda Performance Award RESIDENCIES, FELLOWSHIPS, AND FESTIVALS The Dallas Chamber Symphony, Composer-in-Residence 2016-2018 • Residency and activities funded by The Arts Community Alliance and National Endowment for the Arts; outreach activities involve working with local students and under-represented audiences, including the Dallas Street Choir and at-risk youth. The Canticle Singers of Baltimore, Composer-in-Residence 2015-Present Composer, New Music on the Point Summer Festival Composers’ Course 2016 The Broken Consort, Composer-in-Residence 2015-2016 The Lunar New Music Ensemble, -

Programme Standing Wave’S 2012-2013 Season

NORTHERNSTANDING WAVE SOCIETY PRESENTS standingVISIONS wave ensemble Tuesday November 6 at The Cultch welcome Welcome to Northern Visions, the first concert of Programme Standing Wave’s 2012-2013 Season. The North, as Glenn Gould called it, “that incredible tapestry of tundra and Two Sides taiga country,” holds a special fascination for many Fabian Svensson [2007] artists, composers, and musicians. Most of the music on flute, clarinet, violin, cello, piano, percussion tonight’s program has in one way or another, passed through a northern filter. Daniel Janke’s Weather Kalais Coming, is a kind of musical diagram of the complex, Thorkell Sigurbjörnsson [1976] shifting patterns of migratory birds seen overhead in his Yukon home. Thorkell Sigurbjörnsson’s Kalais describes flute, windhose a Wind God from Icelandic mythology. Norwegian composer Rolf Wallin’s The Age of Wire and String, The Light Within based on chapters of Ben Marcus’ audacious book of John L. Adams [2007] the same name, is cryptic yet funny; alienating, yet flute, clarinet, violin, cello, piano, percussion, tape beautiful. Fabian Svensson’s Two Sides is essentially an argument (actually a near-rumble!), in which the INTERMISSION utterly opposed “sides” circle around one another, speaking the same harmonic language, yet stubbornly The Age of Wire and String and aggressively refusing to agree. Alaskan composer Rolf Wallin [2005] John Luther Adams’ The Light Within, which is based on flute, clarinet, violin, viola, piano the large-scale installation art of James Turrell, serves as a metaphor for the “northern” experience which each 1. Snoring, Accidental Speech piece on tonight’s concert touches on: at first, the music 2. -

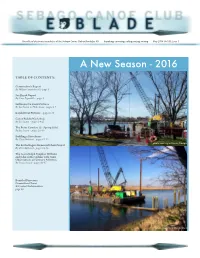

EBLADE May 2016 Page 2 COMMODORE’S REPORT by Walter Lewandowski

The official electronic newsletter of the Sebago Canoe Club in Brooklyn, NY kayaking, canoeing, sailing, racing, rowing May 2016 Vol. 83, Issue 1 A New Season - 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS: Commodore’s Report By Walter Lewandowski - page 3 Sea Kayak Report By Tony Pignatello - page 4 Sail Report & Event Pictures By Jim Luton & Holly Sears - pages 5-7 Kayak Event Pictures - pages 8-13 Canoe Paddle Workshop By Jim Luton - pages 14-25 The Point Comfort 23 - Spring 2016 By Jim Luton - pages 26-40 Building a Shavehorse By Chris Bickford - pages 41-42 photo courtesy of Bonnie Aldinger The Kevin Rogers Memorial Chair Project By Chris Bickford - pages 43-45 The Sea in Ralph Vaughan Williams and John Luther Adams with Some Observations on Literary Affinities By Denis Sivack - pages 46-47 Board of Directors, Committee Chairs & Contact Information page 48 photo courtesy of Chris Bickford A New Dock photo courtesy of John Wright photo courtesy of John Wright EBLADE May 2016 page 2 COMMODORE’S REPORT By Walter Lewandowski Hail Sebago, A spring report from the outer banks of North Carolina. Later in this Once again, we successfully completed our annual dues collec- issue you will read about all the projects, trips and activities planned for tion well before our on-water activities commenced. Thanks again for this season. Here we will talk about all the business of Sebago. everyone’s cooperation. This has put us in position to better plan and Thankfully our dock is finally back in shape just in time for our May budget for our ambitious range of programs, including those that let us events. -

Symphony Ludwig Van Beethoven Was a German Composer Who Lived from 1770 to 1827 and Was Born in the City of Bonn to a Father Who Was a Musician

BOB COLE CONSERVATORY SYMPHONY JOHANNES MULLER-STOSCH, MUSIC DIRECTOR FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 5, 2016 8:00PM CARPENTER PERFORMING ARTS CENTER PLEASE SILENCE ALL ELECTRONIC MOBILE DEVICES. PROGRAM Andante & Allegro from Saxophone Concerto ............................................................................................... Henri Tomasi (1901-1971) Paul Cotton—alto saxophone BCCM 2015/2016 INSTRUMENTAL CONCERTO COMPETITION WINNER Knoxville-Summer of 1915 .................................................................................................................................Samuel Barber (1910-1981) Jeannine Robertson—soprano BCCM 2015/2016 VOICE CONCERTO COMPETITION WINNER Erin Hobbs—graduate conductor INTERMISSION* Symphony No. 3 in E-flat major, Op. 55 “Eroica” ...........................................................................Ludwig van Beethoven Allegro con brio (1770-1827) Marcia funebre: Adagio assai Scherzo: Allegro vivace Finale: Allegro molto ** You may text: (562) 774-2226 or email: [email protected] to ask question about the orchestra or today’s program during intermission. A few of the incoming questions will be addressed during the second half of the program. PROGRAM NOTES Saxophone Concerto Henri Tomasi was born on August 17, 1901 in Marseilles, France, where he developed a fascination with life at sea, and as a child hoped to one day be a sailor. His course quickly changed when his father saw young Henri’s potential as a musician, and enrolled him in the Conservatory of Marseilles. He later attended the Paris Conservatory at the age of 16, and won several prestigious prizes for his works, including the Prix de Rome. He was both composer and conductor, however he later retired as conductor and focused solely on composing. Tomasi composed his Concerto for Saxophone in 1949. It was a competition piece written for Marcel Mule, one of his earlier professors of saxophone in the Paris Conservatory. -

Department of Music Center for the Arts Recital Hall

Department of Music Center for the Arts Recital Hall College Music Society, Mid Atlantic Chapter Composers’ Concert II New Chamber, Vocal, and Solo Works Saturday, April 1, 2017 10:00 AM Calle veneziana Kye Ryung Park Christopher Dillon, piano (b. 1974) in generationes sempiternas… Bradley S. Green Erika Binsley, horn (b. 1989) L’Etere del Tempo Keith Kramer Emily Madsen, oboe; Christopher Dillon, piano (b. 1968) two Souls for the Space of one J. M. Smith Christopher Dillon, piano (b. 1992) The Bunyip: a folktale retelling Thomas Dempster Douglas O’Connor, alto saxophone (b. 1980) Mandala of the Dark Waves Douglas Buchanan Lily Josefsberg, piccolo (b. 1984) Andrew Kwon, viola; Jasmine Hogan, harp Batter my heart, three-person’d God Buchanan Sara Woodward and Clair Galloway Weber, sopranos Lucy McVeigh, mezzo soprano Purgatory Branch (Winter) Dempster Leneida Crawford, mezzo soprano; Terry Ewell, bassoon Indelible Imprint L. A. Logrande Douglas O’Connor, alto saxophone; Nathan Cornelius, guitar (b. 1963) A Seeker’s Song Gregory Mertl Nathan Cornelius, guitar (b. 1969) Please silence all electronic devices. The use of recording equipment and flash photography without prior permission of the Department of Music is strictly prohibited. For your own safety, look for your nearest exit. In case of emergency, walk; do not run to that exit. Program Notes Park: Calle veneziana is inspired by my impressions and experiences in Venice. It depicts a beautiful day I spent exploring the charming scenery along the hidden streets. It begins with the mysterious and capricious morning in Venice. Once the day begins, the second section echoes the present beauty of Venice on its busy streets crowded with tourists. -

LIVING AMERICAN COMPOSERS: NEW MUSIC from BOWLING GREEN Broadcast Schedule – Winter 2018

LIVING AMERICAN COMPOSERS: NEW MUSIC FROM BOWLING GREEN Broadcast Schedule – Winter 2018 PROGRAM #: MBG 18-01 RELEASE: December 28, 2017 TITLE: Close Up with Jennifer Higdon, Part I DESCRIPTION: Composer and Bowling Green State University Alumna Jennifer Higdon co-hosts this episode, which features her own works plus the first installment in her 6-part subseries “Living Women Composers.” J. Higdon: Flute Poetic Jan Vinci, flute Reiko Uchida, piano Troy1649 Du Yun: When a Tiger Meets a Rosa Rugosa Hilary Hahn, violin Cory Smythe, piano DG B0019103 J. Higdon: Viola Concerto Roberto Diaz, viola Nashville Symphony/Guerrero Naxos 8.559823 PROGRAM #: MBG 18-02 RELEASE: January 4, 2018 TITLE: Close Up with Jennifer Higdon, Part II DESCRIPTION: Composer and Bowling Green State University Alumna Jennifer Higdon co-hosts this episode, which features her own works plus the second installment in her 6-part subseries, “Living Women Composers” with composer Libby Larsen. J. Higdon: All Things Majestic Nashville Symphony/Guerrero Naxos 8.559823 Libby Larsen: Four on the Floor Kentucky Center Chamber Players New Dynamic J. Higdon: On the Death of the Righteous Mendelssohn Club of Philadelphia/Harler Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia Innova 806 J. Higdon: Loco (excerpt) Fort Worth Symphony/Harth-Bedoya Fort Worth Symphony Orchestra PROGRAM #: MBG 18-03 RELEASE: January 11, 2018 TITLE: Festival 2016 DESCRIPTION: We hear concert performances from the 2016 New Music Festival at Bowling Green State University. Also, Jennifer Higdon profiles the music of Marilyn -

E PLURIBUS by CURTIS N. SMITH Submitted to the Faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUScholarWorks E PLURIBUS BY CURTIS N. SMITH Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University December 2017 ii Accepted by the faculty of the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music Doctoral Committee _________________________________________________________ Aaron Travers, Chair and Research Director _________________________________________________________ Don Freund _________________________________________________________ P.Q. Phan December 4, 2017 iii iv CURTIS N. SMITH E Pluribus SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA 2017 v Program Notes This piece is about the individual and the collective, and is inspired by democracy. There are two main characters—the ocean of sound, represented most prominently by the strings—especially at the beginning and end, and a tonal chord progression that emerges gradually from the dense cluster at the beginning of the piece. The sublimation of the tonal progression into the cluster and the cluster’s interaction with the tonal progression propel the piece, delineate structure, and act as a type of embodiment for the societal shifts and interactions experienced in a democracy. The tonal chord progression is a quotation and adaptation of the strings part from Charles Ives’s The Unanswered Question. I turn to Ives and this specific piece for three main reasons. First, I had the United States of America in mind while preparing to write this piece and Ives is arguably the founding father of America’s independent compositional voice. -

An Evening of Video Game Music

An Evening of Video Game Music The WMGSO is a community orchestra and choir whose mission is to share and celebrate video game music with as wide an audience as possible, primarily by putting on affordable, accessible concerts in the D.C. area. Game music weaves a complex melodic thread through the traditions, shared memories, values, and mythos of an entire international and intergenerational culture. WMGSO showcases this music because it largely escapes recognition in professional circles. The result: classical music with a 21st-century twist, drawing non-gamers to the artistic merits of video game soundtracks, and attracting new audiences to orchestral concert halls. Board of Executives Staff Music Director Nigel Horne Choirmaster Jacob Coppage-Gross President Ayla Hurley Ensemble Manager Evan Schefstad Vice President Joseph Wang Music Librarian Zeynep Dilli Secretary Mimi Herrmann Assistant Treasurer Patricia Lesley Treasurer Chris Apple Small Ensemble Director Katie Noble Development Director Jessie Biele Event Coordinator Emily Monahan Public Relations Director Melissa Apter Assistant Public Relations Mary Beck About the Music Director WMGSO’s Music Director is Nigel Horne. Nigel is an experienced conductor, clinician and composer, with a degree in band studies from the University of Sheffield, England, and a Master of Philosophy in Free Composition from the University of Leeds. Nigel has also directed the Rockville Brass Band since 2009. WMGSO is supported in part by funding from the Montgomery County Government and the Arts and Humanities Council of Montgomery County. WMGSO is licensed by the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers. Our Supporters WMGSO relies on the generosity of our Supporters to help defray the costs of everything from venue rental to music license purchases. -

The Music of John Luther Adams / Edited by Bernd Herzogenrath

The Farthest Place * * * * * * * * * The Farthest Place The Music of John Luther �dams Edited by Bernd Herzogenrath � Northeastern University Press Boston northeastern university press An imprint of University Press of New England www.upne.com © 2012 Northeastern University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Designed by Eric M. Brooks Typeset in Arnhem and Aeonis by Passumpsic Publishing University Press of New England is a member of the Green Press Initiative. The paper used in this book meets their minimum requirement for recycled paper. For permission to reproduce any of the material in this book, contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Suite 250, Lebanon NH 03766; or visit www.upne.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The farthest place: the music of John Luther Adams / edited by Bernd Herzogenrath. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-1-55553-762-3 (cloth: alk. paper)— isbn 978-1-55553-763-0 (pbk.: alk. paper)— isbn 978-1-55553-764-7 1. Adams, John Luther, 1953– —Analysis, appreciation. I. Herzogenrath, Bernd, 1964–. ml410.a2333f37 2011 780.92—dc23 2011040642 5 4 3 2 1 * For Frank and Janna Contents Acknowledgments * ix Introduction * 1 bernd herzogenrath 1 Song of the Earth * 13 alex ross 2 Music as Place, Place as Music The Sonic Geography of John Luther Adams * 23 sabine feisst 3 Time at the End of the World The Orchestral Tetralogy of John Luther Adams * 48 kyle gann 4 for Lou Harrison * 70 peter garland 5 Strange Noise, Sacred