Red Diamond Newsletter (BMA Ctr)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syria: 'Nowhere Is Safe for Us': Unlawful Attacks and Mass

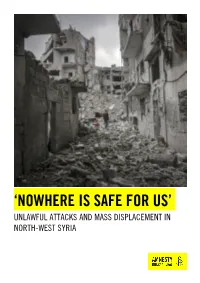

‘NOWHERE IS SAFE FOR US’ UNLAWFUL ATTACKS AND MASS DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH-WEST SYRIA Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2020 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons Cover photo: Ariha in southern Idlib, which was turned into a ghost town after civilians fled to northern (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, international 4.0) licence. Idlib, close to the Turkish border, due to attacks by Syrian government and allied forces. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode © Muhammed Said/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2020 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: MDE 24/2089/2020 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF NORTH-WEST SYRIA 4 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 2. METHODOLOGY 8 3. BACKGROUND 10 4. ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES AND SCHOOLS 12 4.1 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES 14 AL-SHAMI HOSPITAL IN ARIHA 14 AL-FERDOUS HOSPITAL AND AL-KINANA HOSPITAL IN DARET IZZA 16 MEDICAL FACILITIES IN SARMIN AND TAFTANAZ 17 ATTACKS ON MEDICAL FACILITIES IN 2019 17 4.2 ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS 18 AL-BARAEM SCHOOL IN IDLIB CITY 19 MOUNIB KAMISHE SCHOOL IN MAARET MISREEN 20 OTHER ATTACKS ON SCHOOLS IN 2020 21 5. -

Ballistic and Blast Resistant Security Solutions Introduction Protecharmored.Com 1-413-445-4000

BALLISTIC AND BLAST RESISTANT SECURITY SOLUTIONS INTRODUCTION PROTECHARMORED.COM 1-413-445-4000 Political, social and terrorist unrest in today’s world requires protection against the harshest ballistic, blast and fragmentation threats utilized around the globe. As a world leader in hard-armor technology, PROTECH® BLAST AND FRAGMENTATION PROTECTION Armor Systems is rapidly becoming the single-source provider of security SOLUTIONSSURVIVABILITY solutions for military, nuclear and government agencies. Using only the PROTECH® Armor Systems provides comprehensive blast analyses to determine most advanced materials and engineering, we offer standard and custom the safe standoff distances for a wide range of explosive threats. structures to provide unsurpassed protection no matter what’s demanded. • Threats ranging from 100 to 10,000 pounds of TNT have been analyzed, From defensive fighting positions, guard booths and guard towers to fully including occupant survivability protected modular ballistic enclosure solutions, PROTECH Armor Systems • Analyses are designed and provided such that the occupant not only survives offers ballistic and blast protection on any level. an attack, but is able to respond after the attack • Safe Standoff Distances (SSD) are provided ensuring the structure meets the required protection when a given standoff is employed TM ® The PROTECH team stands ready to meet all of your ballistic, • Analyses are available for installation tie-down considerations, tower use, blast and fragmentation protection requirements. & foundation design ™ • More than 30 years of ballistic design and technology experience Our exclusive ARMOR-LOK design offers seamless 360-degree protection to all areas • Broad range of small arm ballistic threats up to .50 AP rounds BALLISTIC PROTECTION US & INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS of the structure including windows, doors • Products manufactured using only the highest quality and most advanced and gunport systems. -

Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “

Was the Syria Chemical Weapons Probe “Torpedoed” by the West? By Adam Larson Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, May 02, 2013 Theme: US NATO War Agenda In-depth Report: SYRIA Since the perplexing conflict in Syria first broke out two years ago, the Western powers’ assistance to the anti-government side has been consistent, but relatively indirect. The Americans and Europeans lay the mental, legal, diplomatic, and financial groundwork for regime change in Syria. Meanwhile, Arab/Muslim allies in Turkey and the Persian Gulf are left with the heavy lifting of directly supporting Syrian rebels, and getting weapons and supplementary fighters in place. The involvement of the United States in particular has been extremely lackluster, at least in comparison to its aggressive stance on a similar crisis in Libya not long ago. Hopes of securing major American and allied force, preferrably a Libya-style “no-fly zone,” always leaned most on U.S. president Obama’s announcement of December 3, 2012, that any use of chemical weapons (CW) by the Assad regime – or perhaps their simple transfer – will cross a “red line.” And that, he implied, would trigger direct U.S. intervention. This was followed by vague allegations by the Syrian opposition – on December 6, 8, and 23 – of government CW attacks. [1] Nothing changed, and the allegations stopped for a while. However, as the war entered its third year in mid-March, 2013, a slew of new allegations came flying in. This started with a March 19 attack on Khan Al-Assal, a contested western district of Aleppo, killing a reported 25-31 people. -

Cultural Heritage Is the Physical Manifestation of a People's History

Witnessing Heritage Destruction in Syria and Iraq Cultural heritage is the physical manifestation of a people’s history and forms a significant part of their identity. Unfortunately, the destruction of that heritage has become an ongoing part of the conflict in Syria and Iraq. With the rise of ISIS and the increase of political instability, important cultural sites and irreplaceable collections are now at risk in these countries and across the region. Mass murder, systematic terror, and forced resettlement have always been tools of ethnic and sectarian cleansing. But events in Syria and Iraq remind us that the erasure of cultural heritage, Map of Syria and Iraq which removes all traces of a people from the landscape, is part of the same violent process. Understanding this loss and responding to it remain a challenge for us all. Exhibit credits: Smithsonian Institution University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology American Association for the Advancement of Science U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield A Syrian inspects a damaged mosque following bomb attacks by Assad regime forces in the opposition-controlled al-Shaar neighborhood of Aleppo, Syria, on September 21, 2015. Conflict in Syria and Iraq (Photo by Ibrahim Ebu Leys/Anadolu Agency/ Getty Images) Recent violence in Syria and Iraq has shattered daily life, leaving over 250,000 people dead and over 12 million displaced. Beginning in 2011, civil protests in Damascus and Daraa against the Assad government were met with a severe crackdown, leading to a civil war and creating a power vacuum within which terror groups like ISIS have flourished. -

Displaced Loyalties: the Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey

Displaced Loyalties: The Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey Kristin Fabbe Chad Hazlett Tolga Sinmazdemir Working Paper 18-024 Displaced Loyalties: The Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey Kristin Fabbe Harvard Business School Chad Hazlett UCLA Tolga Sinmazdemir Bogazici University Working Paper 18-024 Copyright © 2017 by Kristin Fabbe, Chad Hazlett, and Tolga Sinmazdemir Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Displaced Loyalties: The Effects of Indiscriminate Violence on Attitudes Among Syrian Refugees in Turkey Kristin Fabbe,∗ Chad Hazlett,y & Tolga Sınmazdemirz December 8, 2017 Abstract How does violence during conflict affect the political attitudes of civilians who leave the conflict zone? Using a survey of 1,384 Syrian refugees in Turkey, we employ a natural experiment owing to the inaccuracy of barrel bombs to examine the effect of having one's home destroyed on political and community loyalties. We find that refugees who lose a home to barrel bombing, while more likely to feel threatened by the Assad regime, are less supportive of the opposition, and instead more likely to say no armed group in the conflict represents them { opposite to what is expected when civilians are captive in the conflict zone and must choose sides for their protection. Respondents also show heightened volunteership towards fellow refugees. Altogether, this suggests that when civilians flee the conflict zone, they withdraw support from all armed groups rather than choosing sides, instead showing solidarity with their civilian community. -

The Reverberating Effects of Explosive Weapon Use in Syria Contents

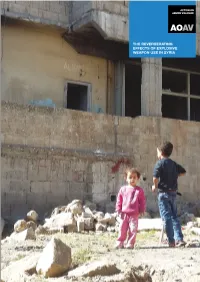

THE REVERBERATING EFFECTS OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPON USE IN SYRIA CONTENTS Introduction 4 1.1 Timeline 6 1.2 Worst locations 8 1.3 Weapon types 11 1.4 Actors 12 Health 14 Economy 19 Environment 24 Society and Culture 30 Conclusion 36 Recommendations 37 Report by Jennifer Dathan Notes 38 Additional research by Silvia Ffiore, Leo San Laureano, Juliana Suess and George Yaolong Editor Iain Overton Copyright © Action on Armed Violence (January 2019) Cover illustration Syrian children play outside their home in Gaziantep, Turkey by Jennifer Dathan Design and printing Tutaev Design Clarifications or corrections from interested parties are welcome Research and publication funded by the Government of Norway, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 4 | ACTION ON ARMED VIOLENCE REVERBERATING EFFECTS OF EXPLOSIVE WEAPONS IN SYRIA | 5 INTRODUCTION The use of explosive weapons, particularly in populated noticed the following year that, whilst total civilian families from both returning to their homes and using areas, causes wide-spread and long-term harm to casualties (deaths and injuries) were just below that their land. Such impact has devastating and lingering civilians. Action on Armed Violence (AOAV) has been of the previous year, civilian deaths had increased by consequences for communities and cultures. monitoring casualties from the use of explosive 50% (from 5,639 in 2016 to 8,463 in 2017). As the war weapons around the globe since 2010. So extreme continued, injuries were increasingly less likely to be In this report, AOAV seeks to better understand the has such harm been in Syria in recent years that, recorded - particularly in incidents where there were reverberating harms from the explosive violence in by the end of 2017, Syria had overtaken Iraq as the high levels of civilian deaths. -

Consumed by War the End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’S Political Order

STUDY Consumed by War The End of Aleppo and Northern Syria’s Political Order KHEDER KHADDOUR October 2017 n The fall of Eastern Aleppo into rebel hands left the western part of the city as the re- gime’s stronghold. A front line divided the city into two parts, deepening its pre-ex- isting socio-economic divide: the west, dominated by a class of businessmen; and the east, largely populated by unskilled workers from the countryside. The mutual mistrust between the city’s demographic components increased. The conflict be- tween the regime and the opposition intensified and reinforced the socio-economic gap, manifesting it geographically. n The destruction of Aleppo represents not only the destruction of a city, but also marks an end to the set of relations that had sustained and structured the city. The conflict has been reshaping the domestic power structures, dissolving the ties be- tween the regime in Damascus and the traditional class of Aleppine businessmen. These businessmen, who were the regime’s main partners, have left the city due to the unfolding war, and a new class of business figures with individual ties to regime security and business figures has emerged. n The conflict has reshaped the structure of northern Syria – of which Aleppo was the main economic, political, and administrative hub – and forged a new balance of power between Aleppo and the north, more generally, and the capital of Damascus. The new class of businessmen does not enjoy the autonomy and political weight in Damascus of the traditional business class; instead they are singular figures within the regime’s new power networks and, at present, the only actors through which to channel reconstruction efforts. -

Manual ENG.Pdf

HISTORY The political crisis has been growing for months. A wave of demonstrations has broken out around the world. The pieces of information released through the mass media hardly reveals half of the seriousness of the situation. And it’s all because of... In a secret session of the Central Geological UN Commission it is revealed that worldwide oil stocks have plummeted to dangerously low levels. If consumption remains at current levels, oil reserves will run out within 10-15 years. This proves too short for even the most highly industrialized countries to switch their economies over to alternative energy sources. Lack of oil leads to a total crash of the world economy, transportation systems, international banking system and, finally, ushers in a period of anarchy and chaos. In September 2001, the UN General Assembly drafted a resolution calling for the takeover of all world oil reserves and placed their control firmly in UN hands. The stated goal was to bring mankind out of the oil crisis with a minimum of pain. The OPEC countries response was to call for a Jihad, or holy war and quickly began building up their arms supplies. The UN then passed another resolution calling for the forcible capture of all oil reserves, starting with those in the Middle East. In November 2001 the first NATO fleet hit the shores of the Persian Gulf... INSTALLING THE GAME You must install World War III: Black Gold game files to your hard drive and have the World War III: Black Gold CD in your CD-ROM drive to play this game. -

Evolution in Military Affairs in the Battlespace of Syria and Iraq

P. MARTON DOI: 10.14267/cojourn.2017v2n2a3 COJOURN 2:2-3 (2017) Evolution in military affairs in the battlespace of Syria and Iraq Péter Marton1 Abstract This paper will consider developments in the Syrian and Iraqi battlespaces that may be conceptualised as relevant to the broader evolution in military affairs. A brief discussion of different notions of „revolution" and „evolution” (in Military Affairs) will be offered, followed by an overview of the combatant actors involved in engagements in the battlespace concerned. The analysis distinguishes at the start between two different evolutionary processes: one specific to the local theatre of war in which local combatants, heavily constrained by their circumstances and limitations, show innovation with limited resources and means, and with very high (existential) stakes. This actually existential evolutionary process is complicated by the effects of the only quasi-evolutionary process of major powers’ interactions (with each other and with local combatants). The latter process is quasi-evolutionary in the sense that it does not carry direct existential stakes for the central players involved in it. The stakes are in a sense virtual: being a function of the prospects of imagined peer-competitor military conflict. Key cases studied in the course of the discussion include (inter alia) the evolution of the Syrian Arab Air Force's use of so-called barrel bombs as well as the use of land-attack cruise missiles and other high-end weaponry by major intervening powers. Keywords: RMA, warfare, militaries, tactics, strategy, Syria, Iraq Introduction: Evolution in military affairs Evolution, in the case of more complex organisms, is the combined effect of genetic re- combination and natural selection that results in the adaptation of different species to their 1 Péter Marton is Associate Professor at Corvinus University’s Institute of International Studies, and Editor- in-Chief of COJOURN. -

The 12Th Annual Report on Human Rights in Syria 2013 (January 2013 – December 2013)

The 12th annual report On human rights in Syria 2013 (January 2013 – December 2013) January 2014 January 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Genocide: daily massacres amidst international silence 8 Arbitrary detention and Enforced Disappearances 11 Besiegement: slow-motion genocide 14 Violations committed against health and the health sector 17 The conditions of Syrian refugees 23 The use of internationally prohibited weapons 27 Violations committed against freedom of the press 31 Violations committed against houses of worship 39 The targeting of historical and archaeological sites 44 Legal and legislative amendments 46 References 47 About SHRC 48 The 12th annual report on human rights in Syria (January 2013 – December 2013) Introduction The year 2013 witnessed a continuation of grave and unprecedented violations committed against the Syrian people amidst a similarly shocking and unprecedented silence in the international community since the beginning of the revolution in March 2011. Throughout the year, massacres were committed on almost a daily basis killing more than 40.000 people and injuring 100.000 others at least. In its attacks, the regime used heavy weapons, small arms, cold weapons and even internationally prohibited weapons. The chemical attack on eastern Ghouta is considered a landmark in the violations committed by the regime against civilians; it is also considered a milestone in the international community’s response to human rights violations Throughout the year, massacres in Syria, despite it not being the first attack in which were committed on almost a daily internationally prohibited weapons have been used by the basis killing more than 40.000 regime. The international community’s response to the crime people and injuring 100.000 drew the international public’s attention to the atrocities others at least. -

The Sudan Consortium the Impact of Sudanese Military Operations On

The Sudan Consortium African and International Civil Society Action for Sudan The impact of Sudanese military operations on the civilian population of Southern Kordofan1 April 2014 The Sudan Consortium works with a trusted group of local Sudanese partners who have been working on the ground in Southern Kordofan since the current conflict began in late 2011. All the attacks referred to in this report were launched against areas where there was no military presence and which were clearly identifiable as civilian in character. We believe that this information provides strong circumstantial evidence that civilians are being directly and deliberately targeted by the Sudanese armed forces in Southern Kordofan. In the last week of April, large numbers of civilians were reported to have been displaced from their homes in Delami County, South Kordofan as a result of a major new military offensive launched in Southern Kordofan by the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF). Although exact numbers are difficult to establish, partners have cited estimates between 45,000 and 70,000. The government offensive in Southern Kordofan appears to have been concentrated on Rashad, Al Abisseya and Delami counties in the north-east of Southern Kordofan. The situation on the ground remains fluid and information from Rashad and Al Abisseya counties has been difficult to obtain. However the Sudan Consortium’s partners on the ground have been able to report firsthand on the situation in Delami County and have interviewed internally displaced persons (IDPs) fleeing from the fighting further north. From 12 April onwards, several locations in Delami County, notably Aberi, Mardis and Sarafyi, were subject to heavy bombardment on a daily basis by artillery and multiple launch rocket systems (MLRS) deployed by the Sudanese Armed Forces. -

About Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ

About Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ Syrians for Truth and Justice /STJ is a nonprofit, nongovernmental, independent Syrian organization. STJ includes many defenders and human rights defenders from Syria and from different backgrounds and affiliations, including academics of other nationalities. The organization works for Syria, where all Syrians, without discrimination, should be accorded dignity, justice and equal human rights. 1 Repeated Attacks with Incendiary Weapons, Cluster Munitions and Chemicals on Eastern Ghouta A Flash Report Documenting the events of 7 March 2018 in Hamoryah and those of 10 and 11 March 2018 in Irbin 2 Introduction Syrian regular forces and their allies continued their heaviest military campaign1 on Eastern Ghouta cities and towns, using various types of weapons, such as rocket launchers “Smerch type”, barrel bombs, guided missiles and incendiary weapons. As on March 7, 2018, the city of Hamoryah2 witnessed a bloody day (following adoption of Security Council Resolution No. 2401), where it was shelled with weapons loaded with incendiary substances, similar to phosphorous, and napalm-like substances. This was accompanied with targeting Hamoryah with a barrel bomb, loaded with toxic gas, dropped by a helicopter on the road between Saqba town and Hamoryah, as confirmed by the field researcher of Syrians for Truth and Justice/STJ. As well as targeting the city with a rocket loaded with cluster munitions the same day. This intensive shelling killed at least 29 civilians, two of whom were burnt to death with incendiary substances, and caused suffocation to scores of civilians as a result of using toxic gas besides the outbreak of fires in residential buildings The hysterical shelling hasn’t spared the city of Irbin3, which was targeted by chemical weapons loaded with incendiary substances similar to phosphorus and others loaded with napalm-like substances, on 10 and 11 March 2018.