Neoclassicism As Ideology Book Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thesis October 11,2012

Demystifying Galina Ustvolskaya: Critical Examination and Performance Interpretation. Elena Nalimova 10 October 2012 Submitted in partial requirement for the Degree of PhD in Performance Practice at the Goldsmiths College, University of London 1 Declaration The work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been presented for any other degree. Where the work of others has been utilised this has been indicated and the sources acknowledged. All the translations from Russian are my own, unless indicated otherwise. Elena Nalimova 10 October 2012 2 Note on transliteration and translation The transliteration used in the thesis and bibliography follow the Library of Congress system with a few exceptions such as: endings й, ий, ый are simplified to y; я and ю transliterated as ya/yu; е is е and ё is e; soft sign is '. All quotations from the interviews and Russian publications were translated by the author of the thesis. 3 Abstract This thesis presents a performer’s view of Galina Ustvolskaya and her music with the aim of demystifying her artistic persona. The author examines the creation of ‘Ustvolskaya Myth’ by critically analysing Soviet, Russian and Western literature sources, oral history on the subject and the composer’s personal recollections, and reveals paradoxes and parochial misunderstandings of Ustvolskaya’s personality and the origins of her music. Having examined all the available sources, the author argues that the ‘Ustvolskaya Myth’ was a self-made phenomenon that persisted due to insufficient knowledge on the subject. In support of the argument, the thesis offers a performer’s interpretation of Ustvolskaya as she is revealed in her music. -

Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet

37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 37 At6( /NO, 116 HARMONIC ORGANIZATION IN AARON COPLAND'S PIANO QUARTET THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By James McGowan, M.Mus, B.Mus Denton, Texas August, 1995 K McGowan, James, Harmonic Organization in Aaron Copland's Piano Quartet. Master of Music (Theory), August, 1995, 86 pp., 22 examples, 5 figures, bibliography, 122 titles. This thesis presents an analysis of Copland's first major serial work, the Quartet for Piano and Strings (1950), using pitch-class set theory and tonal analytical techniques. The first chapter introduces Copland's Piano Quartet in its historical context and considers major influences on his compositional development. The second chapter takes up a pitch-class set approach to the work, emphasizing the role played by the eleven-tone row in determining salient pc sets. Chapter Three re-examines many of these same passages from the viewpoint of tonal referentiality, considering how Copland is able to evoke tonal gestures within a structural context governed by pc-set relationships. The fourth chapter will reflect on the dialectic that is played out in this work between pc-sets and tonal elements, and considers the strengths and weaknesses of various analytical approaches to the work. -

Stravinsky, the Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance,"

/N81 AI2319 Ti VILSKY' USE OF IEhPIAN IN HIS ORCHESTRAL WORKS THE IS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State College in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of M1- JiROF JU.SIC by Wayne Griffith, B. Mus. Conway, Arkansas January, 1955 TABLE OF CONTENT4 Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . ,.. , , * . Chap ter I. THE USE OF PIANO1E A' Al ORCTHE TL I:ThUERIMT BEFOR 1910 . , , . , , l STRAICY II. S U6 OF 2E PIANO S E114ORCHES L ORK HIS OF "RUSIA PERIOD . 15 The Fire-Bird Pe~trouchka Le han u hossignol III. STAVIL C ' 0 USE OF TE PI 40IN 9M ORCHESTRAL .RKS OF HIS "NEO-CLASSIO" PERIOD . 56 Symphonyof Psalms Scherzo a la Russe Scenes IBfallet Symphony~in Three Movements BIIORPHYy * - . 100 iii 1I3T OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure Page 1. Berlioz, Leio, Finale, (from Berlioz' Treatise on Instrumentation, p . 157) . 4 2. Saint-Saena, ym phony in 0-minor, (from Prof. H. Kling's Modern Orchestration and Instrumentation, a a.~~~~*f0" 0. 7 p. 74) . 0 0 * * * 3. Moussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation Scene,'" 36-40 mm.f . -a - - --. " " . 10 4. oussorgsky, Boris Godunov, "Coronation :scene," mm. 241-247 . f . * . 11 5. imsky-Korsakoff, Sadko , (from rimkir -Korsakoff' s Principles of 0rchtiration, Lart II, p. 135) . 12 6. ximsky-Korsakoff, The Snow aiden, (from Zimsky torsatoff'c tTTrin~lecs ofhOrchestration, Part II, . 01) . - - . - . * - - . 12 7 . i s akosy-. o Rf, TVe <now %aiN , (f 0r 1;i s^ky Korsaoif ' s Prciniles of Orchestration, Part II, 'p. 58) . aa. .a. .a- -.-"- -a-a -r . .". 13 8. Stravinsky, The Fire-Bird, "The Fire-Bird's Dance," 9. -

PAUL HINDEMITH (1895-1963) in the Later Years of His Life Paul Hindemith Had Become a Somewhat Neglected Figure

TEMPO A QUARTERLY REVIEW OF MODERN MUSIC Edited by Colin Mason © 1964 by Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd. PAUL HINDEMITH (1895-1963) In the later years of his life Paul Hindemith had become a somewhat neglected figure. Once ranked with Stravinsky and Bartok among the most stimulating experimenters of the 1920s, he later began to lose his hold on the public, and his influence on younger composers declined, especially after 1945, when serialism started to spread widely, leaving him very much isolated in his hostility to it. Now that that issue no longer greatly agitates the musical world, it is becom- ing possible to assess more clearly the importance and individuality of his con- tribution to 20th-century music. An obvious comparison is with his compatriot of a generation earlier, Max Reger, who was similarly prolific, and in his early days was reckoned daring, but whose work later revealed an academic streak. In Hindemith one might call it rather an intellectual, rational and philosophical streak, not fatal but injurious to the spontaneous play of his musical imagination. As early as 193 1 he wrote an oratorio Das Unaufhorliche, to a text by Gottfried Benn which mocks at human illusions of what is enduring, including (besides learning, science, religion and love) art. Hindemith's choice of such a subject seems to have been symptomatic of some scepticism on his own part about art, and although his innate creative musical genius could not be repressed, it was made to struggle for survival against the theoretical restraints that he insisted on imposing upon it. -

University of Oklahoma

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE THE PIANO CONCERTOS OF PAUL HINDEMITH A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts By YANG-MING SUN Norman, Oklahoma 2007 UMI Number: 3263429 UMI Microform 3263429 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 THE PIANO CONCERTOS OF PAUL HINDEMITH A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY Dr. Edward Gates, chair Dr. Jane Magrath Dr. Eugene Enrico Dr. Sarah Reichardt Dr. Fred Lee © Copyright by YANG-MING SUN 2007 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is dedicated to my beloved parents and my brother for their endless love and support throughout the years it took me to complete this degree. Without their financial sacrifice and constant encouragement, my desire for further musical education would have been impossible to be fulfilled. I wish also to express gratitude and sincere appreciation to my advisor, Dr. Edward Gates, for his constructive guidance and constant support during the writing of this project. Appreciation is extended to my committee members, Professors Jane Magrath, Eugene Enrico, Sarah Reichardt and Fred Lee, for their time and contributions to this document. Without the participation of the writing consultant, this study would not have been possible. I am grateful to Ms. Anna Holloway for her expertise and gracious assistance. Finally I would like to thank several individuals for their wonderful friendships and hospitalities. -

Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum

Performance Practice Review Volume 1 Article 6 Number 1 Spring/Fall Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Musicology Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Buxbaum, Erica Heisler (1988) "Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le Sacre," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 1: No. 1, Article 6. DOI: 10.5642/ perfpr.198801.01.6 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol1/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stravinsky, Tempo, and Le sacre Erica Heisler Buxbaum Performing the works of Igor Stravinsky precisely as he intended would appear to be an uncomplicated matter: Stravinsky notated his scores in great detail, conducted recorded performances of many of his works, and wrote commentaries that contain a great deal of specific performance information. Stravinsky's recordings and published statements, however, raise as many questions as they answer about the determination of tempo and the documentary value of recordings. Like Wagner, Stravinsky believed that the establishment of the proper tempo for a work was crucial and declared that "a piece of mine can survive almost anything but wrong or uncertain tempo." Stravinsky notated his tempi precisely with both Italian words and metronome markings and asserted on many occasions that the primary value of his recordings was that they demonstrated the proper tempi for his works. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

Stravinsky Oedipus

London Symphony Orchestra LSO Live LSO Live captures exceptional performances from the finest musicians using the latest high-density recording technology. The result? Sensational sound quality and definitive interpretations combined with the energy and emotion that you can only experience live in the concert hall. LSO Live lets everyone, everywhere, feel the excitement in the world’s greatest music. For more information visit lso.co.uk LSO Live témoigne de concerts d’exception, donnés par les musiciens les plus remarquables et restitués grâce aux techniques les plus modernes de Stravinsky l’enregistrement haute-définition. La qualité sonore impressionnante entourant ces interprétations d’anthologie se double de l’énergie et de l’émotion que seuls les concerts en direct peuvent offrit. LSO Live permet à chacun, en toute Oedipus Rex circonstance, de vivre cette passion intense au travers des plus grandes oeuvres du répertoire. Pour plus d’informations, rendez vous sur le site lso.co.uk Apollon musagète LSO Live fängt unter Einsatz der neuesten High-Density Aufnahmetechnik außerordentliche Darbietungen der besten Musiker ein. Das Ergebnis? Sir John Eliot Gardiner Sensationelle Klangqualität und maßgebliche Interpretationen, gepaart mit der Energie und Gefühlstiefe, die man nur live im Konzertsaal erleben kann. LSO Live lässt jedermann an der aufregendsten, herrlichsten Musik dieser Welt teilhaben. Wenn Sie mehr erfahren möchten, schauen Sie bei uns Jennifer Johnston herein: lso.co.uk Stuart Skelton Gidon Saks Fanny Ardant LSO0751 Monteverdi Choir London Symphony Orchestra Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) The music is linked by a Speaker, who pretends to explain Oedipus Rex: an opera-oratorio in two acts the plot in the language of the audience, though in fact Oedipus Rex (1927, rev 1948) (1927, rev 1948) Cocteau’s text obscures nearly as much as it clarifies. -

COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, and PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice

Blurring the Border: Copland, Chávez, and Pan-Americanism Item Type text; Electronic Thesis Authors Sierra, Candice Priscilla Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 28/09/2021 23:10:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/634377 BLURRING THE BORDER: COPLAND, CHÁVEZ, AND PAN-AMERICANISM by Candice Priscilla Sierra ________________________________ Copyright © Candice Priscilla Sierra 2019 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the FRED FOX SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2019 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Musical Examples ……...……………………………………………………………… 4 Abstract………………...……………………………………………………………….……... 5 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Chapter 1: Setting the Stage: Similarities in Upbringing and Early Education……………… 11 Chapter 2: Pan-American Identity and the Departure From European Traditions…………... 22 Chapter 3: A Populist Approach to Politics, Music, and the Working Class……………....… 39 Chapter 4: Latin American Impressions: Folk Song, Mexicanidad, and Copland’s New Career Paths………………………………………………………….…. 53 Chapter 5: Musical Aesthetics and Comparisons…………………………………………...... 64 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………. 82 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………….. 85 4 LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES Example 1. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r17-1 to r18+3……………………………... 69 Example 2. Copland, Three Latin American Sketches: No. 3, Danza de Jalisco (1959–1972), r180+4 to r180+8……………………………………………………………………...... 70 Example 3. Chávez, Sinfonía India (1935–1936), r79-2 to r80+1…………………………….. -

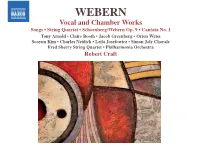

ANTON WEBERN Vol

WEBERN Vocal and Chamber Works Songs • String Quartet • Schoenberg/Webern Op. 9 • Cantata No. 1 Tony Arnold • Claire Booth • Jacob Greenberg • Orion Weiss Sooyun Kim • Charles Neidich • Leila Josefowicz • Simon Joly Chorale Fred Sherry String Quartet • Philharmonia Orchestra Robert Craft THE ROBERT CRAFT COLLECTION Four Songs for Voice and Piano, Op. 12 (1915-17) 5:28 THE MUSIC OF ANTON WEBERN Vol. 3 & I. Der Tag ist vergangen (Day is gone) Text: Folk-song 1:32 Recordings supervised by Robert Craft * II. Die Geheimnisvolle Flöte (The Mysterious Flute) Text by Li T’ai-Po (c.700-762), from Hans Bethge’s ‘Chinese Flute’ 1:32 Five Songs from Der siebente Ring (The Seventh Ring), Op. 3 (1908-09) 5:35 ( III. Schien mir’s, als ich sah die Sonne (It seemed to me, as I saw the sun) Texts by Stefan George (1868-1933) Text from ‘Ghost Sonata’ by August Strindberg (1849-1912) 1:32 1 I. Dies ist ein Lied für dich allein (This is a song for you alone) 1:19 ) IV. Gleich und gleich (Like and Like) 2 II. Im Windesweben (In the weaving of the wind) 0:36 Text by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) 0:52 3 III. An Bachesranft (On the brook’s edge) 1:00 Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano 4 IV. Im Morgentaun (In the morning dew) 1:04 5 V. Kahl reckt der Baum (Bare stretches the tree) 1:36 Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Producer: Philip Traugott • Engineer: Tim Martyn • Editor: Jacob Greenberg • Assistant engineer: Brian Losch Tony Arnold, Soprano • Jacob Greenberg, Piano Recorded at the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, on 28th September, 2011 Three Songs from Viae inviae, Op. -

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN

RECORDED RICHTER Compiled by Ateş TANIN Previous Update: February 7, 2017 This Update: February 12, 2017 New entries (or acquisitions) for this update are marked with [N] and corrections with [C]. The following is a list of recorded recitals and concerts by the late maestro that are in my collection and all others I am aware of. It is mostly indebted to Alex Malow who has been very helpful in sharing with me his extensive knowledge of recorded material and his website for video items at http://www.therichteracolyte.org/ contain more detailed information than this list.. I also hope for this list to get more accurate and complete as I hear from other collectors of one of the greatest pianists of our era. Since a discography by Paul Geffen http://www.trovar.com/str/ is already available on the net for multiple commercial issues of the same performances, I have only listed for all such cases one format of issue of the best versions of what I happened to have or would be happy to have. Thus the main aim of the list is towards items that have not been generally available along with their dates and locations. Details of Richter CDs and DVDs issued by DOREMI are at http://www.doremi.com/richter.html . Please contact me by e-mail:[email protected] LOGO: (CD) = Compact Disc; (SACD) = Super Audio Compact Disc; (BD) = Blu-Ray Disc; (LD) = NTSC Laserdisc; (LP) = LP record; (78) = 78 rpm record; (VHS) = Video Cassette; ** = I have the original issue ; * = I have a CD-R or DVD-R of the original issue. -

20Th Century Foxtrots • 2 Germany

includes WORLD PREMIÈRE RECORDINGS EUGEN D’ALBERT SIEGFRIED BORRIS FIDELIO F. FINKE WALTER GOEHR Public Domain Private Collection Public Domain Courtesy of the Goehr family 20TH CENTURY FOXTROTS • 2 GERMANY PAUL HINDEMITH WALTER NIEMANN KURT WEILL STEFAN WOLPE With kind permission from the © Dipl.-Ing. Gerhard Helzel, Courtesy of the Kurt Weill Courtesy of the Akademie der Hindemith Foundation Edition Romana Hamburg Foundation Künste, Berlin GOTTLIEB WALLISCH, piano GOTTLIEB WALLISCH TH 20 CENTURY FOXTROTS • 2 Born in Vienna, Gottlieb Wallisch first appeared on the concert platform when he was seven years old, and at the age of twelve GERMANY made his debut in the Golden Hall of the Vienna Musikverein. A BORNSCHEIN • BORRIS • BUTTING • D’ALBERT • ERDMANN concert directed by Yehudi Menuhin in 1996 launched Wallisch’s FINKE • GIESEKING • GOEHR • HERBST • HINDEMITH international career: accompanied by the Sinfonia Varsovia, the seventeen-year-old pianist performed Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ KÜNNEKE • MITTMANN • NIEMANN • SEKLES • WEILL • WOLPE Concerto. GOTTLIEB WALLISCH, piano Since then Wallisch has received invitations to the world’s most prestigious concert halls and festivals including Carnegie Hall in Catalogue Number: GP814 New York, Wigmore Hall in London, the Cologne Philharmonie, Recording Dates: 21–23 October, 2019 the Tonhalle Zurich, the NCPA in Beijing, the Ruhr Piano Festival, Recording Venue: Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Berlin-Dahlem, Germany the Beethovenfest in Bonn, the Festivals of Lucerne and Salzburg, Producer and Editor: Boris Hofmann © Andrej Grilc December Nights in Moscow, and the Singapore Arts Festival. Engineer: Henri Thaon Conductors with whom he has performed as a soloist include Piano: Steinway, Model D #544.063 Giuseppe Sinopoli, Sir Neville Marriner, Dennis Russell Davies, Kirill Petrenko, Louis Langrée, Piano Technician: Martin Jerabek Lawrence Foster, Christopher Hogwood, Martin Haselböck and Bruno Weil.