No Substitute for Experience

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Partisan Balance with Bite

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2018 Partisan Balance with Bite Daniel Hemel Brian D. Feinstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel Hemel & Brian Feinstein, "Partisan Balance with Bite," 118 Columbia Law Review 9 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COLUMBIA LAW REVIEW VOL. 118 JANUARY 2018 NO. 1 ARTICLE PARTISAN BALANCE WITH BITE Brian D. Feinstein* & Daniel J. Hemel** Dozens of multimember agencies across the federal government are subject to partisan balance requirements, which mandate that no more than a simple majority of agency members may hail from a single party. Administrative law scholars and political scientists have questioned whether these provisions meaningfully affect the ideological composition of federal agencies. In theory, Presidents can comply with these require- ments by appointing ideologically sympathetic members of the opposite party once they have filled their quota of same-party appointees (i.e., a Democratic President can appoint liberal Republicans or a Republican President can appoint conservative Democrats). No multiagency study in the past fifty years, however, has examined whether—in practice— partisan balance requirements actually prevent Presidents from selecting like-minded individuals for cross-party appointments. This Article fills that gap. We gather data on 578 appointees to twenty-three agencies over the course of six presidencies and thirty-six years. -

George HW Bush and CHIREP at the UN 1970-1971

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2020 The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971 James W. Weber Jr. University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian History Commons, Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Weber, James W. Jr., "The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971" (2020). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2756. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2756 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Cut is the Deepest : George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970–1971 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by James W. -

For Immediate Release Contact

For Immediate Release Contact: Jenny Parker McCloskey, 215-409-6616 Merissa Blum, 215-409-6645 [email protected] [email protected] BEST-SELLING AUTHOR, JON MEACHAM, VISITS NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER TO UNVEIL HIS UPCOMING BIOGRAPHY ON GEORGE H.W. BUSH Copy of “Destiny and Power” included with admission Philadelphia (November 4, 2015) – Best-selling author and Pulitzer Prize-winning historian, Jon Meacham, visits the National Constitution Center on Thursday, November 12th at 7 p.m. for an America’s Town Hall discussion on his latest biography, Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush, which is set to be released November 10th. Meacham’s biography pulls from a number of sources, many of which have never been available to the public, including journal entries from both President Bush and his wife, Barbara. The biography follows Bush throughout his life, detailing his childhood as well as his rise through the ranks of politics. Highlights include the former president’s time in the Navy during World War II following the attack on Pearl Harbor and becoming the first president since John Adams to live to see his son become president of the United States. Meacham’s past works include his Pulitzer Prize-winning biography on Andrew Jackson, American Lion and best-selling biography, Thomas Jefferson: The Art of Power. Admission to this event is $25 for National Constitution Center Members and $30 for the public. All guests will receive a copy of Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush. A special book signing opportunity with Jon Meacham will follow the program. -

The Evolution of Political Rhetoric: the Year in C-SPAN Archives Research

The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research Volume 6 Article 1 12-15-2020 The Evolution of Political Rhetoric: The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research Robert X. Browning Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse Recommended Citation Browning, Robert X. (2020) "The Evolution of Political Rhetoric: The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research," The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research: Vol. 6 Article 1. Available at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol6/iss1/1 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. The Evolution of Political Rhetoric: The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research Cover Page Footnote To purchase a hard copy of this publication, visit: http://www.thepress.purdue.edu/titles/format/ 9781612496214 This article is available in The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/ccse/vol6/iss1/1 THE EVOLUTION OF POLITICAL RHETORIC THE YEAR IN C-SPAN ARCHIVES RESEARCH Robert X. Browning, Series Editor The C-SPAN Archives, located adjacent to Purdue University, is the home of the online C-SPAN Video Library, which has copied all of C-SPAN’s television content since 1987. Extensive indexing, captioning, and other enhanced online features provide researchers, policy analysts, students, teachers, and public offi- cials with an unparalleled chronological and internally cross-referenced record for deeper study. The Year in C-SPAN Archives Research presents the finest interdisciplinary research utilizing tools of the C-SPAN Video Library. -

Masculinity in American Television from Carter to Clinton Bridget Kies University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations May 2018 Masculinity in American Television from Carter to Clinton Bridget Kies University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Kies, Bridget, "Masculinity in American Television from Carter to Clinton" (2018). Theses and Dissertations. 1844. https://dc.uwm.edu/etd/1844 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MASCULINITY IN AMERICAN TELEVISION FROM CARTER TO CLINTON by Bridget Kies A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English at The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee May 2018 ABSTRACT MASCULINITY IN AMERICAN TELEVISION FROM CARTER TO CLINTON by Bridget Kies The University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, 2018 Under the Supervision of Professor Tasha Oren This dissertation examines American television during a period I call the long 1980s. I argue that during this period, television became invested in new and provocative images of masculinity on screen and in networks’ attempts to court audiences of men. I have demarcated the beginning and ending of the long 1980s with the declaration of Jimmy Carter as Time magazine’s Man of the Year in 1977 and Bill Clinton’s inauguration in 1993. This also correlates with important shifts in the television industry, such as the formation of ESP-TV (later ESPN) in 1979 and the end of Johnny Carson’s tenure as host of The Tonight Show on NBC in 1992. -

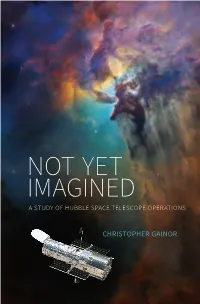

Not Yet Imagined: a Study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations

NOT YET IMAGINED A STUDY OF HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OPERATIONS CHRISTOPHER GAINOR NOT YET IMAGINED NOT YET IMAGINED A STUDY OF HUBBLE SPACE TELESCOPE OPERATIONS CHRISTOPHER GAINOR National Aeronautics and Space Administration Office of Communications NASA History Division Washington, DC 20546 NASA SP-2020-4237 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Gainor, Christopher, author. | United States. NASA History Program Office, publisher. Title: Not Yet Imagined : A study of Hubble Space Telescope Operations / Christopher Gainor. Description: Washington, DC: National Aeronautics and Space Administration, Office of Communications, NASA History Division, [2020] | Series: NASA history series ; sp-2020-4237 | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: “Dr. Christopher Gainor’s Not Yet Imagined documents the history of NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope (HST) from launch in 1990 through 2020. This is considered a follow-on book to Robert W. Smith’s The Space Telescope: A Study of NASA, Science, Technology, and Politics, which recorded the development history of HST. Dr. Gainor’s book will be suitable for a general audience, while also being scholarly. Highly visible interactions among the general public, astronomers, engineers, govern- ment officials, and members of Congress about HST’s servicing missions by Space Shuttle crews is a central theme of this history book. Beyond the glare of public attention, the evolution of HST becoming a model of supranational cooperation amongst scientists is a second central theme. Third, the decision-making behind the changes in Hubble’s instrument packages on servicing missions is chronicled, along with HST’s contributions to our knowledge about our solar system, our galaxy, and our universe. -

Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author Jon Meacham Among Impressive

PRESS RELEASE For Immediate Release Pulitzer Prize-Winning Author Jon Meacham among Impressive Lineup of Authors for 22nd Annual A Celebration of Reading 2016 Celebration to support Former First Lady Barbara Bush’s local & national literacy efforts HOUSTON – The Barbara Bush Houston Literacy Foundation announces a stellar lineup of authors for the 22nd annual A Celebration of Reading fundraising event in Houston. This year’s outstanding lineup includes Pulitzer Prize-winning author Jon Meacham, New York Times Bestselling Authors Brad Meltzer, Kelly Corrigan, and Dr. David Eagleman, and award-winning author and broadcaster Scott Simon. This event, hosted by former First Lady Barbara Bush and Maria and Neil Bush, co-chairs of the Barbara Bush Houston Literacy Foundation, will be held on Thursday, April 21, 2016 at the Hobby Center for the Performing Arts. “Maria and I are delighted to chair this special event,” stated Neil Bush. “We are always deeply honored to be a part of such an important night that not only increases awareness of the literacy crisis in our community, but that also raises funds to help increase literacy rates across Houston and the rest of the country. In the words of my mother and First Lady Barbara Bush: ‘If you help a person to read, then their opportunities in life will be endless.’” Phillips 66 will serve as the Title Sponsor of A Celebration of Reading for a second year in a row. The company’s continued involvement in this event demonstrates its leadership in supporting Houston literacy efforts by advancing the Foundation’s mission to improve the quality of life through the power of literacy – the ability to read, write, speak clearly, and think critically. -

Boogie Man Discussion Guide Intro What Historical Information Did You

Boogie Man Discussion Guide intro What historical information did you learn from this film? What emotions did it elicit? Did you feel empathy for Lee Atwater? Former Atwater intern Tucker Eskew says "You can't understand American politics if you don't understand Lee Atwater." Do you agree? What classic American traits does Atwater embody? What adjectives would you use to describe him? Director Stefan Forbes has referred to the title Boogie Man as a triple-entendre. What different meanings might this phrase have? What relevance does this film have to recent political campaigns? Are these connections obvious? Would you have preferred the film spell them out more, or do you prefer films that allow the viewers to make connections themselves? the rebel Do you believe Atwater was anti-establishment, as he claims? If so, how? Do you feel there’s irony in his use of the term? What other ironies do you find in his life and career? Ed Rollins compares Atwater to Billy the Kid. To what other figures in politics, literature and film might you compare him? Is Atwater a hero or an anti-hero, in the classic definitions of the terms? the backlash What did Strom Thurmond teach Atwater about race, class, and wedge issues? What positive effects did he have on Atwater? What negative ones? Did resentment, as Tucker Eskew states, really become the future of the Republican party? If so, how? What were the causes of this resentment? Did things like the Civil Rights movement and LBJ’s Great Society program play a part in it? Howard Fineman says Atwater made the GOP a Southern party. -

The All-Volunteer Force and Presidential Use of Military Force

The All-Volunteer Force and Presidential Use of Military Force David S. Nasca Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts In Political Science Karen M. Hult, Chair Priya Dixit Brandy Faulkner 19 September 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: U.S. presidents, Military, National Defense, All-Volunteer Force, public approval, defense expenditures, war casualties Copyright 2019, David S. Nasca The All-Volunteer Force and Presidential Use of Military Force David S. Nasca ABSTRACT The creation of the All-Volunteer Force (AVF) in 1973 allowed U.S. presidents to deploy American military power in times and places of their own choosing with fewer concerns that the electorate would turn against their leadership. A reaction to the trauma of the Vietnam War, the AVF did away with conscription and instead relied on volunteers to serve and fight in U.S. military operations. The AVF’s ranks were mostly filled with those willing to deploy and fight for their country, without the U.S. having to rely on conscription. When U.S. presidents had to use the AVF to fight in conflicts, they could expect to enjoy a higher degree of public support than those presidents who led the U.S. military during the Korean and Vietnam wars. Drawing from casualty, financial, and public opinion statistics from 1949 through 2016, this thesis argues that with the adoption of the AVF in 1973 U.S. presidents have been better able to deploy the AVF in combat with less resistance from the American people. -

[email protected]

Order any of these books today by contacting your Readers Advisor at 1-800-742-7691 | 1-402-471-4038 | [email protected] U.S. PRESIDENTS – Forty-first to Current (HISTORIES AND BIOGRAPHIES) (available on digital cartridge) PRESIDENTS: Forty-first President George Bush, (1989-1993) – Vice President(s) Dan Quayle, (1989-1993) Biographies: DB 80060 41: A Portrait of My Father by George W. Bush (7 hours, 44 minutes) The author, the forty-third president of the United States, profiles his father, George H.W. Bush, the forty-first president of the United States. Details the elder Bush’s early life in Massachusetts, service during World War II, and career in the oil industry, the CIA, and politics. Unrated. Commercial audiobook. 2014. DB 82900 Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush by Jon Meacham (25 hours, 12 minutes) Drawing on extensive interviews and access to family diaries and papers, Meacham charts Bush’s rise from county party chairmanship to congressman, UN ambassador, head of the Republican National Committee, envoy to China, director of the CIA, vice president under Ronald Reagan, and, finally, president of the United States. Unrated. Commercial audiobook. 2015. Related Books: DB 38873 Barbara Bush: A Memoir by Barbara Bush (26 hours, 2 minutes) Drawing upon her diaries, tapes, letters, and from a "very selective memory of the early days," Barbara Bush shares the experiences of what she calls a life of "privilege of every kind." She writes of the first years of the Bushes’ marriage; the births of their children and the death of one; the campaign trail; the world leaders she met; the White House years; and of life after the presidency. -

Us National Security Strategy

The Strategist U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY STRATEGY: LESSONS LEARNED PAUL LETTOW 117 U.S. National Security Strategy: Lessons Learned The Biden administration, as well as future administrations, should look to the national security strategy planning efforts of previous administrations for lessons on how to craft a strategy that establishes a competitive approach to America’s rivals that is both toughminded and sustainable in order to guide U.S. foreign, defense, and budget policies and decision-making. In this article, Paul Lettow gives a history of the processes and strategies of past administrations, beginning with the Eisenhower administration, and draws out the lessons to be learned from them. n keeping with the practice of U.S. admin- efforts of previous administrations for lessons on istrations for the past several decades, the how to do just that. A number of those lessons are Biden administration is likely to produce positive but are underappreciated today — and a national security strategy within its first some are cautionary, pointing to flaws in outlook yearI or two. Indeed, it has already signaled that it or process that the Biden administration and fu- will begin work on one.1 It will do so while con- ture administrations ought to avoid. fronting an international environment character- Most presidents since Harry Truman have pro- ized by increasingly intense geopolitical challenges duced a written national security strategy, or some- to the United States — most prominently and com- thing akin to it. During the Cold War, national se- prehensively from China, but also from a Russia curity strategies often took the form of a classified determined to play spoiler and destabilizer when written directive to executive branch departments and where it can, and from Iran, North Korea, and and agencies as part of a systematic planning pro- other powers and threats at a more regional level. -

Open Door NATO and Euro-Atlantic Security After the Cold War

Open Door NATO and Euro-Atlantic Security After the Cold War Daniel S. Hamilton and Kristina Spohr Editors Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies Johns Hopkins University Daniel S. Hamilton and Kristina Spohr, eds., Open Door: NATO and Euro- Atlantic Security After the Cold War. Washington, DC: Foreign Policy Institute/Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs, Johns Hopkins University SAIS 2019. © Foreign Policy Institute/Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs, Johns Hopkins University SAIS, 2019 Supported by Funded by Distributed by Brookings Institution Press. Foreign Policy Institute and Henry A. Kissinger Center for Global Affairs Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies Johns Hopkins University 1717 Massachusetts Ave., NW Washington, DC 20036 Tel: (202) 663-5882 Email: [email protected] http://transatlanticrelations.org https://www.fpi.sais-jhu.edu/ https://www.kissinger.sais-jhu.edu ISBN: 978-1-7337339-2-2 Front cover stamp images reproduced with permission: Czech Republic stamp: Graphic designer: Zdeněk Ziegler 1999 Engraver: Bohumil Šneider 1999 Hungarian stamp: Copyright: Magyar Posta 1999 (Dudás L.) Polish stamp: Copyright: Poczta Polska/Polish Post 1999 Contents Acknowledgments .................................................. vii Foreword ........................................................ix Madeleine K. Albright Introduction ....................................................xiii Daniel S. Hamilton and Kristina Spohr Part I: The Cold War Endgame and NATO Transformed Chapter