1 Catholic Missions in Kingston Upon Thames, 1850

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Growth of London Through Transport Map of London’S Boroughs

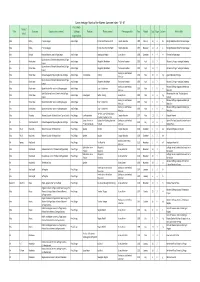

Kingston The growth of London through transport Map of London’s boroughs 10 The map shows the current boundaries of London’s Key boroughs. The content of 2 1 Barking 17 Hillingdon this album relates to the & Dagenham 15 31 18 Hounslow area highlighted on the map. 14 26 2 Barnet 16 19 Islington This album is one of a 3 Bexley 20 Kensington series looking at London 17 4 6 12 19 4 Brent & Chelsea boroughs and their transport 1 25 stories from 1800 to the 5 Bromley 21 Kingston 9 30 present day. 33 7 6 Camden 22 Lambeth 23 Lewisham 7 City of London 13 20 28 8 Croydon 24 Merton 18 11 3 9 Ealing 25 Newham 22 32 23 26 Redbridge 27 10 Enfield 11 Greenwich 27 Richmond 28 Southwark 24 12 Hackney 29 Sutton Kingston 13 Hammersmith 21 5 & Fulham 30 Tower Hamlets 29 8 14 Haringey 31 Waltham Forest 15 Harrow 32 Wandsworth 16 Havering 33 Westminster A3 RICHMOND RIVER A307 THAMES ROAD KINGSTON A308 UPON Kingston Hill THAMES * * Kings Road Kingston A238 Turks Pier Norbiton * * Bentalls A3 * Market Place NEW * Cambridge* A2043 Road MALDEN Estates New Malden A307 Kingston Bridge Berrylands KINGSTON SURBITON RIVER THAMES UPON KINGSTON BY PASS THAMES Surbiton A240 A3 Malden Beresford Avenue* Manor Worcester Park A243 A309 A240 A3 Tolworth Haycroft* Estate HOOK A3 0 miles ½ 1 Manseld* Chessington Road North 0 kilometres 1 Chessington South A243 A3 A243 * RBK. marked are at theLocalHistoryRoom page. Thoseinthecollection atthebottomofeach are fortheimages References the book. can befoundatthebackof contributing tothisalbum Details ofthepartner theseries. -

Mayor John Williams & Kingston's Fairfield. a Tribute To

MAYOR JOHN WILLIAMS & KINGSTON’S FAIRFIELD. A TRIBUTE TO JUNE SAMPSON, LOCAL HISTORIAN & JOURNALIST. David A Kennedy, PhD 25 NOVEMBER 2019 ABSTRACT John Williams, Mayor of Kingston in 1858, 1859 and 1864, was an energetic, public-spirited, self-educated man who had poor and humble beginnings. He came to Kingston in 1851 to take over the ailing Griffin Hotel which he developed into a flourishing enterprise that was highly regarded. He was instrumental in securing the Fairfield as a recreation ground for the townsfolk and played a part in improving the Promenade on the River Thames. While he acquired enemies, notably Alderman Frederick Gould, his civic funeral in 1872 and obituary tributes indicated that overall he was a greatly respected and valued man. Local historian June Sampson’s view that John Williams deserved greater recognition in Kingston was justified and a memorial in the Fairfield would seem appropriate for this. INTRODUCTION In 2006, June Sampson, distinguished local historian who was formerly the Surrey Comet’s Features Editor, wrote that Kingston upon Thames owed The Fairfield recreation ground to John Williams, who was Mayor of the town in 1858, 1859 and 1864.1 Earlier, she gave a fuller account of Williams’ struggle to have the Fairfield enclosed for the people, which came to fruition in 1865. However, it was not until 1889, after John Williams died in 1872, that the Fairfield was completely laid out and formally opened with a celebratory cricket match. June acknowledged the support that Williams received from Russell Knapp, the owner and editor of the Surrey Comet newspaper, which appeared to be her main source. -

Small Mammals of Kingston Upon Thames AF42018

MAMMALS OF KINGSTON UPON THAMES 1998-2017 Abstract The Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames (RBK) is a small borough of which approximately 13% is open land. Despite policies at all levels to favour ‘sustainable development’ and ‘green infrastructure’, as well as numerous local initiatives, development pressure continues to diminish the boroughs’ open spaces and wildlife habitats. Due to the proximity of good quality habitats in neighbouring boroughs, as well as strong boundary features, a surprising thirty-two species of mammal were recorded in the borough between 1998 - 2018. The all too familiar pressures and initiatives to counter them are considered in the first part of this paper and is followed by a Directory of the Mammals of Kingston, a presentation of the records to date. RBK and its Habitats Open Spaces in the borough RBK has a small amount of open land, estimates vary between 13%-17%. Land designated as Public Open Space accounts for 7.5% (276.68 ha) and Sites of Nature Conservation Importance or SNCI land 10% (377.35 ha) [last updates to SNCIs received in 2010) (GIGL, 2013]. In considering the presence/absence of fauna, no borough can be seen in isolation and has to be considered in the context of, at least, the surrounding boroughs and their open land: fifty-five per cent of the adjacent Borough of Richmond upon Thames (LBRuT) is open land. Boundary features (especially rivers) and large areas of ‘publicly owned land’ used as grazing pasture or leased to golf courses, ensure that RBK retains an important wildlife interest. The RBK borough boundary is twentyseven miles long and borders two Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) - Richmond Park National Nature Reserve (NNR) and Special Site of Scientific Interest (SSSI) (45 ha in RBK) and Wimbledon Common SSSI (4.9 ha in RBK). -

Person Index M-N Pceditfinal.Xlsx

Surrey Heritage: March of the Women: Surname Index ‐ "M ‐ N" Pro or Anti‐ Name/ Title Surname Organisations named Suffrage Position Places named Newspaper title Year Month Day Page Column Article title Initial organisation Miss Mabey Primrose League Anti‐Suffrage St Paul's Hall‐Thornton heath Croydon Guardian 1908 February 22 5 d‐eEdridge Habitation of the Primrose League Miss Mabey Primrose League St Paul's Hall, Thornton Heath Croydon Guardian 1907 November 16 10 e Edridge Habitation of the Primrose League Mrs Macaird National Women's Anti‐Suffrage League Anti‐Suffrage Beechwood, Reigate Surrey Mirror 1908 December 4 4 H The Anti‐Suffrage League Epsom division of Women's National Anti‐Suffrage Mr G. MacAndrew Anti‐Suffrage Village Hall, Mickleham The Surrey Advertiser 1909 April 10 7 Women’s Suffrage: meeting at Camberley League Epsom division of Women's National Anti‐Suffrage Mrs G. MacAndrew Anti‐Suffrage Village Hall, Mickleham The Surrey Advertiser 1909 April 10 7 Women’s Suffrage: meeting at Camberley League Dorking and Leatherhead Miss MacAndrew National League for Opposing Women's Suffrage Anti‐Suffrage In attendance Dorking 1911 May 27 8 f‐gAgainst Women's Suffrage Advertiser Epsom division of Women's National Anti‐Suffrage Miss MacAndrew Anti‐Suffrage Village Hall, Mickleham The Surrey Advertiser 1909 April 10 7 Women’s Suffrage: meeting at Camberley League Dorking and Leatherhead Women's Suffrage. Opposition Meeting at Miss MacAndrew Epsom Division Women's Anti‐Suffrage League Anti‐Suffrage Epsom; Mickleham 1909 May 1 8 h Advertiser Mickleham South East Surrey Branch Women's Anti‐Suffrage Women and the Vote. -

ST-RAPHAELS-WAR-MEMORIAL.Pdf

BEHIND THE NAMES. THE MEMORIAL TO THE PARISH DEAD OF THE GREAT WAR, 1914-1919, AT ST. RAPHAEL’S ROMAN CATHOLIC CHURCH, KINGSTON UPON THAMES DAVID A. KENNEDY, PhD 25 June 2019 ABSTRACT The War Memorial at St. Raphael’s Roman Catholic Church, Kingston upon Thames KT1 2NA, was installed in 1921, probably at the expense of the church’s owner, Captain, The Honourable George Savile. It lists the names of 50 parishioners; 47 men and three women. An attempt was made to compile biographical notes for each person from computerised databases and other sources. A best match was sought for each name, i.e., someone who, on a balance of probabilities in the light of the accumulated evidence, was most likely to be a person behind a name on the memorial. Most of the men served in the British forces and thirteen appeared to be Belgian citizens who probably were known to parishioners who were Belgian refugees. A British woman was killed during a German air-raid on London by shrapnel from an anti-aircraft gun. Two French sisters, assumed to be known to an existing parishioner, were killed in a church during a German long-range bombardment of Paris. One man did not die in the Great War and the name of a brother appeared to have been substituted for a sailor who died in the War. One soldier, stationed in England, was murdered by a comrade of unsound mind. In the time available, it was impossible to compile biographical notes for most of the Belgians and some of the British names, because of lack of information. -

Download It As A

Richmond History JOURNAL OF THE RICHMOND LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY Numbers 1–39 (1981–2018): Contents, Author Index and Subject Index This listing combines, and makes available online, two publications previously available in print form – Journal Numbers 1 to X: Contents and Index, republished with corrections in October 2006, and Journal Numbers XI to XXV: Contents and Index, published in November 2004. This combined version has been extended to cover all issues of Richmond History up to No. 39 (2018) and it also now includes an author index. Journal numbers are in Arabic numerals and are shown in bold. Although we have taken care to check the accuracy of the index we are aware that there may be some inaccuracies, inconsistencies or omissions. We would welcome any corrections or additions – please email them to [email protected] List of Contents There were two issues in 1981, Richmond History's first year of publication. Since then it has been published annually. No. 1: 1981 The Richmond ‘Riverside Lands’ in the 17th Century James Green Vincent Van Gogh in Richmond and Petersham Stephen Pasmore The development of the top of Richmond Hill John Cloake Hesba Stretton (1832–1911), Novelist of Ham Common Silvia Greenwood Richmond Schools in the 18th and 19th centuries Bernard J. Bull No. 2: 1981 The Hoflands at Richmond Phyllis Bell The existing remains of Richmond Palace John Cloake The eccentric Vicar of Kew, the Revd Caleb Colton, 1780–1832 G. E. Cassidy Miscellania: (a) John Evelyn in 1678 (b) Wordsworth’s The Choir of Richmond Hill, 1820 Augustin Heckel and Richmond Hill Stephen Pasmore The topography of Heckel’s ‘View of Richmond Hill Highgate, 1744’ John Cloake Richmond in the 17th century – the Friars area James Green No. -

Display PDF in Separate

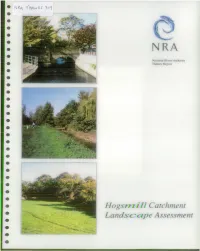

N NRA National Rivers Authority Thames Region H ogsrrrill Catchment L andscape Assessment -2 * ,,t HOGSMILL CATCHMENT LANDSCAPE ASSESSMENT Report prepared by WS Atkins Planning Consultants on behalf of National Rivers Authority Thames Region April 1994 NRA Landscape Architecture Group WS Atkins Planning Consultants National Rivers Authority Woodcote Grove, Ashley Road Thames Region Epsom, Surrey KT18 5BW Kings Meadow House, Kings Meadow Road Tel: (0372) 726140 Reading, Berkshire RG1 8DQ Fax: (0372) 740055 Tel: 0734 535000 Fax: 0734 500388 F2530/REP1/1 EN VIR O N M EN T A G E N C Y RCA/jeh : III III III 111 1 0 2 3 3 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are grateful to the following for giving information and help in compiling this report. National Rivers Authority - Thames Region Kevin Patrick Landscape Architect Dave Webb Conservation Officer Frances Bayley Conservation Officer (Surveys) Neil Dunlop Pollution Officer Dave Leeming Biologist Karen Hills Geomorphology David van Beeston Operations Manager Tributaries Surrey County Council John Edwards County Ecologist Local Authorities Jeff Grace Parks and Royal Borough of Andrew Watson Horticulture Section Kingston Upon Thames James Brebner Planning Department Royal Borough of Kingston Upon Thames John Biglin Countryside Development Borough of Officer Epsom and Ewell Other Organisations Nick Owen Project Officer Lower Mole Countryside Management Project Michael Waite London Ecology Unit CONTENTS Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Purpose of study 1 Methodology 2 Structure of Report 3 2. DEVELOPMENT OF THE LANDSCAPE 5 Physical Influences 5 Human Influences 9 3. NATURE CONSERVATION VALUE 19 Wildlife habitats adjacent to the river 19 Biological survey of the river 21 River corridor survey 22 4. -

Surrey History XII 2013

CONTENTS Seething Wells, Surbiton The Reeds of Oatlands: A Tudor Marriage Settlement The suppression of the Chantry College of St Peter, Lingfield Accessions of Records in Surrey History Centre, 2012 Index to volumes VIII to XII VOLUME XII 2013 SurreyHistory - 12 - Cover.indd 1 15/08/2013 09:34 SURREY LOCAL HISTORY COMMITTEE PUBLICATIONS SURREY ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY Chairman: Gerry Moss, 10 Hurstleigh Drive, Redhill, Surrey, RH1 2AA The former Surrey Local History Council produced Surrey History for many years and the majority of the back numbers are still available. In addition the following extra publications are in print: The Surrey Local History Committee, which is a committee of the Surrey Views of Surrey Churches Archaeological Society, exists to foster an interest in the history of Surrey. It does by C.T. Cracklow this by encouraging local history societies within the county, by the organisation (reprint of 1826 views) of meetings, by publication and also by co-operation with other bodies, to discover 1979 £7.50 (hardback) the past and to maintain the heritage of Surrey, in history, architecture, landscape and archaeology. Pastors, Parishes and People in Surrey The meetings organised by the Committee include a one-day Symposium on by David Robinson a local history theme and a half-day meeting on a more specialised subject. The 1989 £2.95 Committee produces Surrey History annually and other booklets from time to time. See below for publications enquires. Old Surrey Receipts and Food for Thought Membership of the Surrey Archaeological Society, our parent body, by compiled by Daphne Grimm local history societies, will help the Committee to express with authority the 1991 £3.95 importance of local history in the county. -

Royal Borough of Kingston Upon Thames Minor Parking Amendments

ROYAL BOROUGH OF KINGSTON UPON THAMES MINOR PARKING AMENDMENTS - VARIOUS LOCATIONS (REF. KINGMAP0040) THE KINGSTON UPON THAMES (FREE PARKING PLACES, LOADING PLACES AND WAITING, LOADING AND STOPPING RESTRICTIONS) (AMENDMENT NO. *) ORDER 202* THE KINGSTON UPON THAMES (CHARGED-FOR PARKING PLACES) (AMENDMENT NO. *) ORDER 202* THE KINGSTON UPON THAMES (PRESCRIBED ROUTES) (AMENDMENT NO. *) TRAFFIC ORDER 202* DOCUMENTS FOR INSPECTION 1. A copy of the notice to appear in the Surrey Comet and the London Gazette on 26th March 2020 2. The Council’s statement of reasons for proposing to make the Orders 3. The draft Orders 4. Plans to indicate the locations and effect of the Orders Available for inspection until further notice ROYAL BOROUGH OF KINGSTON UPON THAMES MINOR PARKING AMENDMENTS - VARIOUS LOCATIONS (REF. KINGMAP0040) The Kingston upon Thames (Free Parking Places, Loading Places and Waiting, Loading and Stopping Restrictions) (Amendment No. *) Order 202*; The Kingston upon Thames (Charged-For Parking Places) (Amendment No. *) Order 202*; and The Kingston upon Thames (Prescribed Routes) (Amendment No. *) Traffic Order 202*. 1. NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the Council of the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames propose to make the above-mentioned Orders under sections 6, 45, 46, 49 and 124 of and Part IV of Schedule 9 to the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, as amended. 2. The general effect of the Orders would be; (a) to introduce a double yellow line “at any time” waiting restriction and a loading restriction (applying from 7 a.m. to 10 a.m. and from 4 p.m. to 7 p.m.) at each of the following existing ‘goods vehicles loading only’ parking places; (i) in High Street, Kingston (outside No. -

Royal Borough of Kingston Upon Thames

ROYAL BOROUGH OF KINGSTON UPON THAMES EXPERIMENTAL CYCLE FACILITIES AND PARKING, WAITING AND LOADING AMENDMENTS – KINGSTON VALE (SW15), KINGSTON HILL AND LONDON ROAD, KINGSTON - MODIFICATION (REF. KINGMAP0037) THE KINGSTON UPON THAMES (PRESCRIBED ROUTES) (NO. 2) EXPERIMENTAL TRAFFIC ORDER 2020 DOCUMENTS FOR INSPECTION 1. A copy of the notice to appear in the Surrey Comet and the London Gazette on 9th July 2020 2. The Council’s statement of reasons for making the Order 3. The made Order 4. Plans to indicate the location and effect of the Order Available for inspection until further notice ROYAL BOROUGH OF KINGSTON UPON THAMES EXPERIMENTAL CYCLE FACILITIES AND PARKING, WAITING AND LOADING AMENDMENTS – KINGSTON VALE (SW15), KINGSTON HILL AND LONDON ROAD, KINGSTON - MODIFICATION (REF. KINGMAP0037) The Kingston upon Thames (Prescribed Routes) (No. 2) Experimental Traffic Order 2020 1. NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the Council of the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames on 6th July 2020 made the above-mentioned Order under section 9 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, as amended by the Local Government Act 1985. 2. Further to the notice published on 6th February 2020 (introducing the above-mentioned experimental scheme, ref. KingMap0037), the general effect of the Order, which will come into force on 20th July 2020, will be to formally introduce mandatory, two-way cycle lanes which will operate at any time in London Road, Kingston, on the north-west side; from No. 177 to the entrance to Princeton Mews; and from Norbiton Hall to No. 147 -

Journal-Index-13-July-2017.Pdf

Richmond History JOURNAL OF THE RICHMOND LOCAL HISTORY SOCIETY Numbers 1–38: Contents, Author Index and Subject Index This listing combines, and makes available online, two publications previously available in print form – Journal Numbers 1 to X: Contents and Index, republished with corrections in October 2006, and Journal Numbers XI to XXV: Contents and Index, published in November 2004. This combined version has been extended to cover all issues of Richmond History up to No. 38 (2017) and it now also includes an author index. Journal numbers are in Arabic numerals and are shown in bold. Although we have taken care to check the accuracy of the index we are are aware that there may be some inaccuracies, inconsistencies or omissions. We would welcome any corrections or additions – please email them to [email protected] List of Contents There were two issues in 1981, Richmond History's first year of publication. Since then it has been published annually. No. 1: 1981 The Richmond ‘Riverside Lands’ in the 17th Century James Green Vincent Van Gogh in Richmond and Petersham Stephen Pasmore The development of the top of Richmond Hill John Cloake Hesba Stretton (1832–1911), Novelist of Ham Common Silvia Greenwood Richmond Schools in the 18th and 19th centuries Bernard J. Bull No. 2: 1981 The Hoflands at Richmond Phyllis Bell The existing remains of Richmond Palace John Cloake The eccentric Vicar of Kew, the Revd Caleb Colton, 1780–1832 G. E. Cassidy Miscellania: (a) John Evelyn in 1678 (b) Wordsworth’s The Choir of Richmond Hill, 1820 Augustin Heckel and Richmond Hill Stephen Pasmore The topography of Heckel’s ‘View of Richmond Hill Highgate, 1744’ John Cloake Richmond in the 17th century – the Friars area James Green No. -

A Glimpse of Kingston Workhouse Infirmary in 1911

A GLIMPSE OF KINGSTON WORKHOUSE INFIRMARY IN 1911 David A Kennedy, PhD 15 June 2020 ABSTRACT The enumerator of the 1911 Census of Kingston Union Workhouse Infirmary was the matron, Miss Annie Smith. Her record and other sources provided information on the institution’s 465 in-patients, 53 resident nurses, two medical officers and 13 resident domestic servants. The Census data indicated the range of afflictions that prevailed within the community, including the workhouse, that was served by the infirmary. The evidence suggested that in 1911 the infirmary consisted of at least three buildings, constructed at different times, and there were separate wards or rooms for patients with contagious diseases, patients with learning difficulties and patients with mental illness. Maternity patients were accommodated in the workhouse. The nursing and medical standards of the infirmary appeared to be high. INTRODUCTION This research was stimulated by an investigation of the life of Catherine McAllister, an assistant matron at Kingston Infirmary who was killed in the Irish Mail train disaster in 1915. Miss McAllister joined the institution just before the Census on the night of 2 April 1911.1 The main objective was to discover more about the patients and staff that she would have met and her place of work. The enumerator of Kingston Union Workhouse Infirmary for the Census of 1911 was Miss Annie Smith, the matron [Figure 1]. She recorded 465 in- patients, of whom 187 were males and 278 were females, with children included in the total. There were 53 resident nurses, including probationers, and 13 resident domestic servants.