The Field-Names of Cnoc A' Mhadain / Sliddery Muir

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Painting Time: the Highland Journals of John Francis Campbell of Islay

SCOTTISH ARCHIVES 2013 Volume 19 © The Scottish Records Association Painting Time: The Highland Journals of John Francis Campbell of Islay Anne MacLeod This article examines sketches and drawings of the Highlands by John Francis Campbell of Islay (1821–85), who is now largely remembered for his contribution to folklore studies in the north-west of Scotland. An industrious polymath, with interests in archaeology, ethnology and geological science, Campbell was also widely travelled. His travels in Scotland and throughout the world were recorded in a series of journals, meticulously assembled over several decades. Crammed with cuttings, sketches, watercolours and photographs, the visual element within these volumes deserves to be more widely known. Campbell’s drawing skills were frequently deployed as an aide-memoire or functional tool, designed to document his scientific observations. At the same time, we can find within the journals many pioneering and visually appealing depictions of upland and moorland scenery. A tension between documenting and illuminating the hidden beauty of the world lay at the heart of Victorian aesthetics, something the work of this gentleman amateur illustrates to the full. Illustrated travel diaries are one of the hidden treasures of family archives and manuscript collections. They come in many shapes and forms: legible and illegible, threadbare and richly bound, often illustrated with cribbed engravings, hasty sketches or careful watercolours. Some mirror their published cousins in style and layout, and were perhaps intended for the print market; others remain no more than private or family mementoes. This paper will examine the manuscript journals of one Victorian scholar, John Francis Campbell of Islay (1821–85). -

Visitarran Opening Post Covid

VisitArran Opening Post Covid Please note this list is as advised by the businesses listed. Please do check times etc as these may change as time moves on. There may also be businesses open who haven't had time to let us know! Business Name Opening Date Hours Website Phone Self Catering Arran Castaways 3/7/2020 https://www.arrancastaways.com/ 0777 75591325 Auchrannie Resort 15/7/20 www.auchrannie.co.uk 01770 302234 Balmichael Glamping 17/7/20 www.balmichaelglamping.co.uk 01770 465 095 Bellevue Farm Cottages 6/7/2020 https://www.bellevue-arran.co.uk/ 01770 860251 Belvedere Cottage 15/7/20 https://www.belvedere-guesthouse.co.uk/ 01770 302397 Clan Hamilton Flat 3/7/2020 www.beachfrontflat.co.uk Online only Dougarie Estate 4/7/2020 www.dougarieestate.co.uk 07970 286536 Greannan Self Catering 18/7/20 www.visitarran.com 01770 860200 Green Brae Barn 3/7/2020 www.cottagesonarran.com 0739 3403072 Hamilton Cottages 3/7/2020 www.hamiltoncottages.co.uk 0776 6220278 Kildonan Farm Cottages 31/7/20 kildonanfarmcottages.co.uk 01770 820324 Kinloch Hotel 15/7/20 www.bw-kinlochhotel.co.uk 01770 860444 Lochside Self Catering Full until mid Nov http://www.lochside-arran.co.uk/ 01770 860276 Millrink Cottages 6/7/2020 www.millrinkarran.co.uk 01770 870256 Oakbank Farm 4/7/2020 www.oakbankfarm.com 01770 600404 Runach Arainn Glamping 3/7/2020 runacharainn.com 01770 870515 Shannochie Cottages 4/7/2020 www.shannochiearran.co.uk 01770 820291 Viewbank Cottage 17/7/20 www.viewbank-arran.co.uk 01770 700326 West Knowe Holiday 18/7/20 https://www.cottageguide.co.uk/westknowe-oldbyre/ -

Migration of Swallows

Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England (I978) vol 6o HUNTERIANA John Hunter, Gilbert White, and the migration of swallows I F Lyle, ALA Library of the Royal College of Surgeons of England Introduction fied than himself, although he frequently sug- gested points that would be worthy of investi- This year is not only the 25oth anniversary of gation by others. Hunter, by comparison, was John Hunter's birth, but it is also I90 years the complete professional and his work as a since the publication of Gilbert White's Nat- comparative anatomist was complemented by ural History and Antiquities of Selborne in White's fieldwork. The only occasion on which December I788. White and Hunter were con- they are known to have co-operated was in temporaries, White being the older man by I768, when White, through an intermediary, eight years, and both died in I 793. Despite asked Hunter to undertake the dissection of a their widely differing backgrounds and person- buck's head to discover the true function of the alities they had two very particular things in suborbital glands in deer3. Nevertheless, common. One was their interest in natural there were several subjects in natural history history, which both had entertained from child- that interested both of them, and one of these hood and in which they were both self-taught. was the age-old question: What happens to In later life both men referred to this. Hunter swallows in winter? wrote: 'When I was a boy, I wanted to know all about the Background and history clouds and the grasses, and why the leaves changed colour in the autumn; I watched the ants, bees, One of the most contentious issues of eight- birds, tadpoles, and caddisworms; I pestered people eenth-century natural history was with questions about what nobody knew or cared the disap- anything about". -

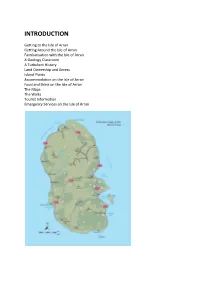

Introduction

INTRODUCTION Getting to the Isle of Arran Getting Around the Isle of Arran Familiarisation with the Isle of Arran A Geology Classroom A Turbulent History Land Ownership and Access Island Plants Accommodation on the Isle of Arran Food and Drink on the Isle of Arran The Maps The Walks Tourist Information Emergency Services on the Isle of Arran THE WALKS Walk 1 Goat Fell and Brodick Walk 2 Brodick Castle and Country Park Walk 3 Brodick and the Clauchland Hills Walk 4 Sheeans and Glen Cloy Walk 5 Lamlash and the Clauchland Hills Walk 6 Sheeans and The Ross Walk 7 Lamlash to Brodick Walk 8 Holy Isle from Lamlash Walk 9 Tighvein and Monamore Glen Walk 10 Tighvein and Urie Loch Walk 11 Glenashdale Falls Walk 12 Glenashdale and Loch na Leirg Walk 13 Lamlash and Kingscross Walk 14 Lagg to Kildonan Coastal Walk Walk 15 Kilmory Forest Circuit Walk 16 Sliddery and Cnocan Donn Walk 17 Tighvein and Glenscorrodale Walk 18 The Ross and Cnoc a' Chapuill Walk 19 Shiskine and Clauchan Glen Walk 20 Ballymichael and Ard Bheinn Walk 21 The String and Beinn Bhreac Walk 22 Blackwaterfoot and King's Cave Walk 23 Machrie Moor Stone Circles Walk 24 Dougarie and Beinn Nuis Walk 25 Dougarie and Sail Chalmadale Walk 26 Circuit of Glen Iorsa Walk 27 Imachar and Beinn Bharrain Walk 28 Pirnmill and Beinn Bharrain Walk 29 Coire Fhion Lochain Walk 30 Catacol and Meall nan Damh Walk 31 Catacol and Beinn Bhreac Walk 32 Catacol and Beinn Tarsuinn Walk 33 Lochranza and Meall Mòr Walk 34 Gleann Easan Biorach Walk 35 Lochranza and Cock of Arran Walk 36 Lochranza and Sail an Im Walk 37 Sannox and Fionn Bhealach Walk 38 North Glen Sannox Horseshoe Walk 39 Glen Sannox Horseshoe Walk 40 Glen Sannox to Glen Rosa Walk 41 Corrie and Goat Fell Walk 42 Glen Rosa and Beinn Tarsuinn Walk 43 Western Glen Rosa Walk 44 Eastern Glen Rosa Appendix 1 The Arran Coastal Way Appendix 2 Gaelic/English Glossary Appendix 3 Useful Contact Information . -

Gaelic Songs of Mary Macleod

Mot.a A^ M(iM£i^^ «''/. A\;-\- "niai^ GAELIC SONGS OF MARY MACLEOD BLACKIE & SON LIMITED so Old Bailey, London 17 Stanhope Street, GLASGOW BLACKIE & SON (INDIA) LIMITED Warwick House, Fort Street, Bombay BLACKIE & SON (CANADA) LIMITED Toronto GAELIC SONGS OF MARY MACLEOD Edited with Introduction, Translation, Notes, etc. BY J. CARMICHAEL WATSON BLACKIE & SON LIMITED LONDON AND GLASGOW 1934 f7 \ o, !SSl f' Printed in Great Britain by Blackie & Son, Ltd., Glasgow Orain agus Luinneagan Gàidhlig le Màiri nighean Alasdair Ruaidh Preface The scarcity of published Gaelic literature, which is one of the chief factors adversely affecting the spoken language, is strikingly illustrated by the fact that the present book is not only the first edition but even the first complete collection of the surviving songs of the poetess of Harris and Skye. She is probably the best of our minor Gaelic bards, and she has been dead for two centuries and a quarter; yet her songs have remained scattered in various scarce books, and only four of them have hitherto been edited. How much of her works is lost to us we can only guess; this book contains all that is known to survive. Circumstances have constrained me to try to meet three needs, the needs of the Gaelic reader, of the Eng- lish reader, and of the schools. In special regard to the first and last, it may be said that the text has been formed on principles stated elsewhere, that the spelling conforms to correct modern standards, and that the apostrophe has been kept strictly in control. -

Macdonald Bards from Mediaeval Times

O^ ^^l /^^ : MACDONALD BARDS MEDIEVAL TIMES. KEITH NORMAN MACDONALD, M.D. {REPRINTED FROM THE "OBAN TIMES."] EDINBURGH NORMAN MACLEOD, 25 GEORGE IV. BRIDGE. 1900. PRBPACB. \y^HILE my Papers on the " MacDonald Bards" were appearing in the "Oban Times," numerous correspondents expressed a wish to the author that they would be some day presented to the pubUc in book form. Feeling certain that many outside the great Clan Donald may take an interest in these biographical sketches, they are now collected and placed in a permanent form, suitable for reference ; and, brief as they are, they may be found of some service, containing as they do information not easily procurable elsewhere, especially to those who take a warm interest in the language and literature of the Highlands of Scotland. K. N. MACDONALD. 21 Clarendon Crescknt, EDINBURGH, October 2Uh, 1900. INDEX. Page. Alexander MacDonald, Bohuntin, ^ ... .. ... 13 Alexander MacAonghuis (son of Angus), ... ... ... 17 Alexander MacMhaighstir Alasdair, ... ... ... ... 25 Alexander MacDonald, Nova Scotia, ... .. .. ... 69 Alexander MacDonald, Ridge, Nova Scotia, ... ... .. 99 Alasdair Buidhe MacDonald, ... .. ... ... ... 102 Alice MacDonald (MacDonell), ... ... .. ... ... 82 Alister MacDonald, Inverness, ... ... .. ... ... 73 Alexander MacDonald, An Dall Mòr, ... ... ... .. 43 Allan MacDonald, Lochaber, ... ... ... ... .. 55 Allan MacDonald, Ridge, Nova Scotia, ... .... ... ... 101 Am Bard Mucanach (Tlie Muck Bard), ... ... .. ... 20 Am Bard CONANACH (The Strathconan Bard), .. ... ... 48 An Aigeannach, -

North Ayrshire Council 29 June 2000

North Ayrshire Council 29 June 2000 Irvine, 29 June 2000 - Minutes of the Meeting of North Ayrshire Council held in the Council Chambers, Cunninghame House, Irvine on Thursday 29 June 2000 at 5.00 p.m. Present Samuel Taylor, Jane Gorman, Thomas Barr, John Bell, Jacqueline Browne, Jack Carson, Gordon Clarkson, John Donn, David Gallagher, James Jennings, Margaret McDougall, Joseph McKinney, Peter McNamara, Elisabethe Marshall, John Moffat, David Munn, Margaret Munn, Alan Munro, David O’Neill, Robert Rae, John Reid, John Sillars and Richard Wilkinson. In Attendance B Devine, Chief Executive; J Travers, Corporate Director (Educational Services); T Orr, Corporate Director (Property Services); and G Irving, Corporate Director (Social Services); A Herbert, Assistant Chief Executive (Finance); I Mackay, Assistant Chief Executive (Legal and Regulatory); B MacDonald, Assistant Chief Executive (Development and Promotion); and G Lawson, Principal Policy Officer (Chief Executive’s). Chair Mr Taylor in the Chair. Apologies for Absence Samuel Gooding, Alan Hill, Ian Clarkson, Stewart Dewar and Elliot Gray. 1. Minutes Confirmed The Minutes of the Meeting of the Council held on 18 May 2000 were confirmed. 2. Reports of Committees The annexed reports of Committees being the Minutes of the Meetings as undernoted were submitted, moved and seconded in terms of Standing Order No. 9 and approved as follows:- Planning and Regulatory Sub-Committee: 22 May 2000 1- 6 Executive and Ratification Committee: 23 May 2000 7 * Educational Services Committee: 24 May 2000 -

A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: an Anti-Johnsonian Venture Hans Utz

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 5 1992 A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture Hans Utz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Utz, Hans (1992) "A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 27: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol27/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hans UIZ A Genevan's Journey to the Hebrides in 1807: An Anti-Johnsonian Venture The book Voyage en Ecosse et aux Iles Hebrides by Louis-Albert Necker de Saussure of Geneva is the basis for my report.! While he was studying in Edinburgh he began his private "discovery of Scotland" by recalling the links existing between the foreign country and his own: on one side, the Calvinist church and mentality had been imported from Geneva, while on the other, the topographic alternation between high mountains and low hills invited comparison with Switzerland. Necker's interest in geology first incited his second step in discovery, the exploration of the Highlands and Islands. Presently his ethnological curiosity was aroused to investigate a people who had been isolated for many centuries and who, after the abortive Jacobite Re bellion of 1745-1746, were confronted with the advanced civilization of Lowland Scotland, and of dominant England. -

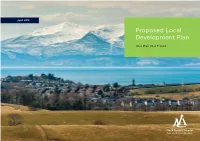

Proposed Local Development Plan

April 2018 Proposed Local Development Plan Your Plan Your Future Your Plan Your Future Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................. 2 Using the Plan ...................................................................................................................4 What Happens Next ...................................................................................................... 5 page 8 page 18 How to Respond .............................................................................................................. 5 Vision .....................................................................................................................................6 Strategic Policy 1: Spatial Strategy ....................................................................... 8 Strategic Policy 1: Strategic Policy 2: Towns and Villages Objective .............................................................................. 10 The Countryside Objective ....................................................................................12 The Coast Objective ..................................................................................................14 Spatial Placemaking Supporting Development Objective: Infrastructure and Services .....16 Strategy Strategic Policy 2: Placemaking ........................................................................... 18 Strategic Policy 3: Strategic Development Areas .....................................20 -

Witch-Hunting and Witch Belief in the Gidhealtachd

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Enlighten Henderson, L. (2008) Witch-hunting and witch belief in the Gàidhealtachd. In: Goodare, J. and Martin, L. and Miller, J. (eds.) Witchcraft and Belief in Early Modern Scotland. Palgrave historical studies in witchcraft and magic . Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 95-118. ISBN 9780230507883 http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/7708/ Deposited on: 1 April 2011 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 CHAPTER 4 Witch-Hunting and Witch Belief in the Gàidhealtachd Lizanne Henderson In 1727, an old woman from Loth in Sutherland was brought before a blazing fire in Dornoch. The woman, traditionally known as Janet Horne, warmed herself, thinking the fire had been lit to take the chill from her bones and not, as was actually intended, to burn her to death. Or so the story goes. This case is well known as the last example of the barbarous practice of burning witches in Scotland. It is also infamous for some of its more unusual characteristics – such as the alleged witch ‘having ridden upon her own daughter’, whom she had ‘transformed into a pony’, and of course, the memorable image of the poor, deluded soul warming herself while the instruments of her death were being prepared. Impressive materials, though the most familiar parts of the story did not appear in print until at least 92 years after the event!1 Ironically, although Gaelic-speaking Scotland has been noted for the relative absence of formal witch persecutions, it has become memorable as the part of Scotland that punished witches later than anywhere else. -

Barluath Additional Musicians: Source at the Royal Conservatoire We Are Creating the Future for Performance

Ainsley Hamill Lead vocals/harmony vocals, Eilidh Firth Fiddle Edward Seaman Highland bagpipes (track 10), border bagpipes (tracks 1, 3 & 9), whistles (tracks 1, 3, 6 & 9), bouzouki (tracks 2, 5 & 8) Colin Greeves Highland bagpipes (track 1), smallpipes (tracks 6 & 9), whistles (tracks 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 8 & 10), clarinet (track 5) Alistair Iain Paterson Piano, synth glockenspiel (track 5), synth bass (track 6) Barluath Additional musicians: Source At the Royal Conservatoire we are creating the future for performance. We provide vocational education at the highest Peter Webster Acoustic guitar (tracks 1, 3, 5 & 9) professional level in dance, drama, music, production, and Dara Stewart Double bass (tracks 2 & 7), screen. We offer an extraordinary blend of intensive tuition, electric bass (1, 3, 5, 8 & 9) world-class facilities, a full performance schedule, the space to collaborate across the disciplines, teaching from renowned John Lowrie Drumkit (tracks 1 & 9), cajon (track 3), staff and international industry practitioners, and unrivalled percussion (track 6) professional partnerships. Find out more at www.rcs.ac.uk David Foley Bódhran (track 8) Special thanks to Bob Whitney, Phil Cunningham, Kenna Campbell, Mairi Barluath MacInnes and Jenn Butterworth for their artistic direction and encouragement. Source We also appreciate the support of John Wallace and Joshua Dickson Produced by Phil Cunningham at The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, as well as Nimbus Alliance All tracks recorded, engineered, for giving us this wonderful opportunity. mixed and mastered by Bob Whitney for The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland/Nimbus Alliance Big thanks to Peter Webster, John Lowrie, Dara Stewart and David Design & Photography by MadeBrave.com Foley for their exceptional musical contributions, and the craic! We would also like to thank Andrew Dobbie and MadeBrave for the photography, album artwork and design. -

Committee Minutes

North Ayrshire Council 4 November 1999 Irvine, 4 November 1999 - Minutes of the Meeting of North Ayrshire Council held in the Council Chambers, Cunninghame House, Irvine on Thursday 4 November 1999 at 5.00 p.m. Present Thomas Barr, John Bell, Jacqueline Browne, Ian Clarkson, John Donn, David Gallagher, Jane Gorman, Elliot Gray, Alan Hill, Margaret McDougall, Joseph McKinney, Elizabeth McLardy, Peter McNamara, Elisabethe Marshall, John Moffat, David Munn, Margaret Munn, Alan Munro, David O’Neill, Robert Rae, John Reid, Samuel Taylor, John Sillars and Richard Wilkinson. In Attendance B Devine, Chief Executive; J Travers, Corporate Director (Educational Services); T Orr, Corporate Director (Property Services); G Irving, Corporate Director (Social Services); A Herbert, Assistant Chief Executive (Finance); I Mackay, Assistant Chief Executive (Legal and Regulatory); B MacDonald, Assistant Chief Executive (Development and Promotion); J Barrett, Assistant Chief Executive (Information Technology); M McCormick, Media Relations Officer; and G Lawson, Principal Policy Officer (Chief Executive’s). Chair Mr Taylor in the Chair. Apologies for Absence Jack Carson, Stewart Dewar, Samuel Gooding and Robert Reilly. 1. Minutes Confirmed The Minutes of the Meeting of the Council held on 23 September 1999 were confirmed. 2. A78 By-Pass The Convener reported that the Transport Minister of the Scottish Parliament had announced the outcome of the Government’s Strategic Road Review. Part of the Review was that a by-pass surrounding the Three Towns (Ardrossan, Saltcoats, Stevenston) on the A78 was to be constructed which would help to alleviate the traffic congestion in that area. The Council and Cunninghame District Council before 1996 had lobbied for the construction of such a by-pass and the Council welcomed this news.