Music, Mime & Metamorphosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Just This Is It: Dongshan and the Practice of Suchness / Taigen Dan Leighton

“What a delight to have this thorough, wise, and deep work on the teaching of Zen Master Dongshan from the pen of Taigen Dan Leighton! As always, he relates his discussion of traditional Zen materials to contemporary social, ecological, and political issues, bringing up, among many others, Jack London, Lewis Carroll, echinoderms, and, of course, his beloved Bob Dylan. This is a must-have book for all serious students of Zen. It is an education in itself.” —Norman Fischer, author of Training in Compassion: Zen Teachings on the Practice of Lojong “A masterful exposition of the life and teachings of Chinese Chan master Dongshan, the ninth century founder of the Caodong school, later transmitted by Dōgen to Japan as the Sōtō sect. Leighton carefully examines in ways that are true to the traditional sources yet have a distinctively contemporary flavor a variety of material attributed to Dongshan. Leighton is masterful in weaving together specific approaches evoked through stories about and sayings by Dongshan to create a powerful and inspiring religious vision that is useful for students and researchers as well as practitioners of Zen. Through his thoughtful reflections, Leighton brings to light the panoramic approach to kōans characteristic of this lineage, including the works of Dōgen. This book also serves as a significant contribution to Dōgen studies, brilliantly explicating his views throughout.” —Steven Heine, author of Did Dōgen Go to China? What He Wrote and When He Wrote It “In his wonderful new book, Just This Is It, Buddhist scholar and teacher Taigen Dan Leighton launches a fresh inquiry into the Zen teachings of Dongshan, drawing new relevance from these ancient tales. -

Donovan Éÿ³æ¨‚Å°ˆè¼¯ ĸ²È¡Œ (ĸ“Ⱦ' & Æ—¶É—´È¡¨)

Donovan 音樂專輯 串行 (专辑 & 时间表) Fairytale https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/fairytale-1401434/songs https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/what%27s-bin-did-and-what%27s-bin-hid- What's Bin Did and What's Bin Hid 860800/songs Lady of the Stars https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/lady-of-the-stars-3216043/songs Cosmic Wheels https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/cosmic-wheels-2002844/songs Brother Sun, Sister Moon https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/brother-sun%2C-sister-moon-2926268/songs 7-Tease https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/7-tease-2818199/songs Essence to Essence https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/essence-to-essence-3058726/songs Slow Down World https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/slow-down-world-3486789/songs Beat Cafe https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/beat-cafe-652824/songs Pied Piper https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/pied-piper-3382622/songs Rising Again https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/rising-again-7336116/songs Love Is Only Feeling https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/love-is-only-feeling-3264170/songs Sixty Four https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sixty-four-3485765/songs Shadows of Blue https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/shadows-of-blue-16999768/songs Ritual Groove https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ritual-groove-3433337/songs One Night in Time https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/one-night-in-time-7093072/songs Sunshine Superman https://zh.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/sunshine-superman-3977083/songs -

Yazoo Discography

Yazoo discography This discography was created on basis of web resources (special thanks to Eugenio Lopez at www.yazoo.org.uk and Matti Särngren at hem.spray.se/lillemej) and my own collection (marked *). Whenever there is doubt whether a certain release exists, this is indicated. The list is definitely not complete. Many more editions must exist in European countries. Also, there must be a myriad of promo’s out there. I have only included those and other variations (such as red vinyl releases) if I have at least one well documented source. Also, the list of covers is far from complete and I would really appreciate any input. There are four sections: 1. Albums, official releases 2. Singles, official releases 3. Live, bootlegs, mixes and samples 4. Covers (Christian Jongeneel 21-03-2016) 1 1 Albums Upstairs at Eric’s Yazoo 1982 (some 1983) A: Don’t go (3:06) B: Only you (3:12) Too pieces (3:12) Goodbye seventies (2:35) Bad connection (3:17) Tuesday (3:20) I before e except after c (4:38) Winter kills (4:02) Midnight (4:18) Bring your love down (didn’t I) (4:40) In my room (3:50) LP UK Mute STUMM 7 LP France Vogue 540037 * LP Germany Intercord INT 146.803 LP Spain RCA Victor SPL 1-7366 Lyrics on separate sheet ‘Arriba donde Eric’ * LP Spain RCA Victor SPL 1-7366 White label promo LP Spain Sanni Records STUMM 7 Reissue, 1990 * LP Sweden Mute STUMM 7 Marked NCB on label LP Greece Polygram/Mute 4502 Lyrics on separate sheet * LP Japan Sire P-11257 Lyrics on separate sheets (english & japanese) * LP Australia Mute POW 6044 Gatefold sleeve LP Yugoslavia RTL LL 0839 * Cass UK Mute C STUMM 7 * Cass Germany Intercord INT 446.803 Cass France Vogue 740037 Cass Spain RCA Victor SPK1 7366 Reissue, 1990 Cass Spain Sanni Records CSTUMM 7 Different case sleeve Cass India Mute C-STUMM 7 Cass Japan Sire PKF-5356 Cass Czech Rep. -

Donovan 2012.Pdf

PERFORMERS PARKE PUTERBAUGH NOT DUST POP LYRICS BUT MODERN POETRY The view o f the sixties is so generalized it’s good to open up the of the Witch”), and the Allman Brothers Band (whose spirituality o f it and what the music was trying to represent. “Mountain Jam” was based on Donovan’s “There Is a It was certainly not just getting stoned and hanging out, man. Mountain”). Beyond all that, he was a gentle spirit who There was meaning and direction; there was substance to it. sang unforgettably of peace, love, enlightenment, wild —Donovan scenes, and magical visions. Born Donovan Leitch in Glasgow, Scotland, in onovan was the Pied Piper of the counterculture. 1946, he moved at age 10 with his family to Hatfield, A sensitive Celtic folk-poet with an adventurous Hertfordshire, England. After turning 1 6, he pursued a musical mind, he was a key figure on the British romantic wanderlust, running off to roam alongside Beat Dscene during its creative explosion in the mid-sixties. He and bohemian circles. He also studiously applied himself wrote and recorded some of the decade’s most memorable to the guitar, learning a sizable repertoire of folk and blues songs, including “Catch the Wind,” “Sunshine Superman,” songs, with the requisite fingerings. A single appearance “Hurdy Gurdy Man,” and “Atlantis.” He charted a dozen during a performance by some friends’ R & B band resulted Top Forty hits in the U.S. and a nearly equal number in the in an offer for Donovan to cut demos in London, which led U.K. -

City Council Approves Treasure Island Lease

Family Owned & Operated for Over 30 Years GREENTECH WILL PROVIDE YOU WITH THE LAWN SERVICE YOU DESERVE A Full Service Lawn Care and Irrigation Service Company With Loyal Customers. · Drug Free Workplace Special Offer · Dependable ONE FREE LAWN AERATION A TTRUERUE CCOMMUNITYOMMUNITY NNEWSPAPEREWSPAPER · Licensed when you sign-up for our full (6) Application Program Your GREENTECH Lawn Program Includes: • 6 Applications of Premium Quality Fertilizer 937-339-4758 • Broadleaf and crabgrass weed control • Ongoing analysis of lawn condition WEEK OF WEDNESDAY MARCH 30, 2016 1-800-LAWN-CARE • Free prompt service calls WWW.TROYTRIB.COM greentechohio.com AF Marathon Medical City Council Approves Consultant Speaks on Injury-Free Running Treasure Island Lease By Brittany Arlene Jackson By Nancy Bowman An agreement between the city of Troy and the Com- munity Improvement Cor- poration (CIC) for the Trea- sure Island Marina Building restaurant/retail operation was called a “positive step” for the facility’s future. The board of the CIC, a non- profit economic development corporation, approved the draft lease document March 25. Dr. Mark Cucuzella Speaks at Up & Running Questions raised at a meet- ing earlier this month on the Dr. Mark Cucuzzella, the Chief Medical Consultant for the three-party agreement (CIC, Air Force Marathon, gave a talk at Up and Running on the city, sublease holder) were Square in downtown Troy on Thursday, March 24. As a pro- answered, said Mark Douglas, fessor of Family Medicine at West Virginia University and CIC treasurer. “All areas that Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Air Force Reserves, Cucuzzel- needed addressed have been,” la is an advocate for injury-free running and teaches about he said. -

Acoustic Sounds Catalog Update

WINTER 2013 You spoke … We listened For the last year, many of you have asked us numerous times for high-resolution audio downloads using Direct Stream Digital (DSD). Well, after countless hours of research and development, we’re thrilled to announce our new high-resolution service www.superhirez.com. Acoustic Sounds’ new music download service debuts with a selection of mainstream audiophile music using the most advanced audio technology available…DSD. It’s the same digital technology used to produce SACDs and to our ears, it most closely replicates the analog experience. They’re audio files for audiophiles. Of course, we’ll also offer audio downloads in other high-resolution PCM formats. We all like to listen to music. But when Acoustic Sounds’ customers speak, we really listen. Call The Professionals contact our experts for equipment and software guidance RECOMMENDED EQUIPMENT RECOMMENDED SOFTWARE Windows & Mac Mac Only Chord Electronics Limited Mytek Chordette QuteHD Stereo 192-DSD-DAC Preamp Version Ultra-High Res DAC Mac Only Windows Only Teac Playback Designs UD-501 PCM & DSD USB DAC Music Playback System MPS-5 superhirez.com | acousticsounds.com | 800.716.3553 ACOUSTIC SOUNDS FEATURED STORIES 02 Super HiRez: The Story More big news! 04 Supre HiRez: Featured Digital Audio Thanks to such support from so many great customers, we’ve been able to use this space in our cata- 08 RCA Living Stereo from logs to regularly announce exciting developments. We’re growing – in size and scope – all possible Analogue Productions because of your business. I told you not too long ago about our move from 6,000 square feet to 18,000 10 A Tribute To Clark Williams square feet. -

Celebrity Playlists for M4d Radio’S Anniversary Week

Celebrity playlists for m4d Radio’s anniversary week Len Goodman (former ‘Strictly’ judge) Monday 28 June, 9am and 3pm; Thursday 1 July, 12 noon “I’ve put together an hour of music that you might like to dance to. I hope you enjoy the music I have chosen for you. And wherever you are listening, I hope it’s a ten from Len!” 1. Putting On The Ritz – Ella Fitzgerald 10. On Days Like These – Matt Monroe 2. Dream A Little Dream of Me – Mama 11. Anyone Who Had A Heart – Cilla Black Cass 12. Strangers On The Shore – Acker Bilk 3. A Doodlin’ Song – Peggy Lee 13. Living Doll – Cliff Richard 4. Spanish Harlem – Ben E King 14. Dreamboat – Alma Cogan 5. Lazy River – Bobby Darin 15. In The Summertime – Mungo Jerry 6. You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me – 16. Clair – Gilbert O’Sullivan Dusty Springfield 17. My Girl – The Temptations 7. When I Need You – Leo Sayer 18. A Summer Place – Percy Faith 8. Come Outside – Mike Sarne & Wendy 19. Kiss Me Honey Honey – Shirley Bassey Richard 20. I Want To Break Free – Queen 9. Downtown – Petula Clark Angela Lonsdale (Our Girl, Holby City, Coronation Street) Thursday 9am and 3pm; Friday 2 July, 12 noon Angela lost her mother to Alzheimer’s. Her playlist includes a range of songs that were meaningful to her and her mother and that evoke family memories. 1. I Love You Because – Jim Reeves (this 5. Crazy – Patsy Cline (her mother knew song reminds Angela of family Sunday every word of this song when she was lunches) in the care home, even at the point 2. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

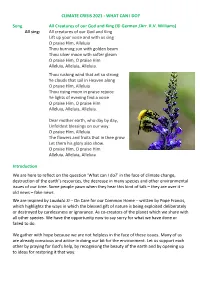

Climate Crisis 2021 - What Can I Do?

CLIMATE CRISIS 2021 - WHAT CAN I DO? Song All Creatures of our God and King (© German /Arr. R.V. Williams) All sing: All creatures of our God and King Lift up your voice and with us sing O praise Him, Alleluia Thou burning sun with golden beam Thou silver moon with softer gleam O praise Him, O praise Him Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia. Thou rushing wind that art so strong Ye clouds that sail in Heaven along O praise Him, Alleluia Thou rising moon in praise rejoice Ye lights of evening find a voice O praise Him, O praise Him Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia. Dear mother earth, who day by day, Unfoldest blessings on our way. O praise Him, Alleluia The flowers and fruits that in thee grow Let them his glory also show. O praise Him, O praise Him Alleluia, Alleluia, Alleluia. Introduction We are here to reflect on the question ‘What can I do?’ in the face of climate change, destruction of the earth’s resources, the decrease in many species and other environmental issues of our time. Some people yawn when they hear this kind of talk – they are over it – old news – fake news. We are inspired by Laudato Si – On Care for our Common Home – written by Pope Francis, which highlights the ways in which the blessed gift of nature is being exploited deliberately or destroyed by carelessness or ignorance. As co-creators of the planet which we share with all other species. We have the opportunity now to say sorry for what we have done or failed to do. -

Samples Top Pop Singles NEW.Vp

DEBUT PEAK WKS ARTIST Ạ=Album Cut Ả=CD ả=Digital DATE POS CHR Song Title ắ=Picture Slv. Ẳ=Cassette ẳ=12" ẵ="45" B-side Label & Number DON & DEWEY Rock and roll duo from Pasadena, California: Don "Sugarcane" Harris (born on 6/18/1938; died on 11/30/1999, age 61) and Dewey Terry (born on 7/17/1937; died of cancer on 5/11/2003, age 65). ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ CLASSIC NON-HOT 100 SONGS ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 1957 (I'm) Leavin' It All Up To You 1957 Jungle Hop 1958 Justine DON & JUAN R&B vocal duo from Brooklyn, New York: Roland "Don" Trone and Claude "Juan" Johnson of The Genies. Don died in May 1982 (age 45). Juan died on 10/31/2002 (age 67). 2/10/62 7 13 1 What's Your Name Chicken Necks Big Top 3079 10/27/62 91 3 2 Magic Wand....................................................................................................................................What I Really Meant To Say Big Top 3121 DON AND THE GOODTIMES Rock and roll band from Portland, Oregon: Don Gallucci (vocals, piano; The Kingsmen), Joey Newman (guitar), Jeff Hawks (tambourine), Buzz Overman (bass) and Bobby Holden (drums). 4/22/67 56 7 1 I Could Be So Good To You ......................................................................................................................And It's So Good ắ Epic 10145 7/29/67 98 1 2 Happy And Me...................................................................................................................If You Love Her, Cherish Her And Such ắ Epic 10199 ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ BREAKOUT HIT ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ 9/4/65 7 3 1 Little Sally Tease [SEA] ...........................................................................................................................Little Green Thing Dunhill 4008 DON, DICK N' JIMMY "Cocktail music" trio: Don Sutton (piano; baritone), Dick Rock (bass; tenor) and Jimmy Cook (acoustic guitar; lead singer). -

Karaoke Listing by Song Title

Karaoke Listing by Song Title Title Artiste 3 Britney Spears 11 Cassadee Pope 18 One Direction 22 Lily Allen 22 Taylor Swift 679 Fetty Wap ft Remy Boyz 1234 Feist 1973 James Blunt 1994 Jason Aldean 1999 Prince #1 Crush Garbage #thatPOWER Will.i.Am ft Justin Bieber 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 1 Thing Amerie 1, 2 Step Ciara Ft Missy Elliott 10,000 Nights Alphabeat 10/10 Paolo Nutini 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan & Miami Sound Machine 1-2-3 Len Barry 18 And Life Skid Row 19-2000 Gorillaz 2 Become 1 Spice Girls To Make A Request: Either hand me a completed Karaoke Request Slip or come over and let me know what song you would like to sing A full up-to-date list can be downloaded on a smart phone from www.southportdj.co.uk/karaoke-dj Karaoke Listing by Song Title Title Artiste 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue 2 Minutes To Midnight Iron Maiden 2 Pints Of Lager & A Packet Of Crisps Please Splognessabounds 2000 Miles The Pretenders 2-4-6-8 Motorway Tom Robinson Band 24K Magic Bruno Mars 3 Words (Duet Version) Cheryl Cole ft Will.I.Am 30 Days The Saturdays 30 Minute Love Affair Paloma Faith 3AM Busted 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 5 Colours In Her Hair McFly 5, 6, 7, 8 Steps 5-4-3-2-1 Manfred Mann 57 Chevrolet Billie Jo Spears 6 Words Wretch 32 6345 789 Blues Brothers 68 Guns The Alarm 7 Things Miley Cyrus 7 Years Lukas Graham 7/11 Beyonce 74-75 The Connells To Make A Request: Either hand me a completed Karaoke Request Slip or come over and let me know what song you would like to sing A full up-to-date list can be downloaded on a smart phone from www.southportdj.co.uk/karaoke-dj -

Forma Y Fondo En El Rock Progresivo

Forma y fondo en el rock progresivo Trabajo de fin de grado Alumno: Antonio Guerrero Ortiz Tutor: Juan Carlos Fernández Serrato Grado en Periodismo Facultad de Comunicación Universidad de Sevilla CULTURAS POP Índice Resumen 3 Palabras clave 3 1. Introducción. Justificación del trabajo. Importancia del objeto de investigación 4 1.1. Introducción 4 1.2. Justificación del trabajo 6 1.3. Importancia del objeto de investigación 8 2. Objetivos, enfoque metodológico e hipótesis de partida del trabajo 11 2.1. Objetivos generales y específicos 11 2.1.1. Objetivos generales 11 2.1.2. Objetivos específicos 11 2.2. Enfoque metodológico 11 2.3. Hipótesis de partida 11 3. El rock progresivo como tendencia estética dentro de la música rock 13 3.1. La música rock como denostado fenómeno de masas 13 3.2. Hacia una nueva calidad estética 16 3.3. Los orígenes del rock progresivo 19 3.4. La difícil definición (intensiva) del rock progresivo 25 3.5. Hacia una definición extensiva: las principales bandas de rock progresivo 27 3.6. Las principales escenas del rock progresivo 30 3.7. Evoluciones ulteriores 32 3.8. El rock progresivo hoy en día 37 3.9. Algunos nombres propios 38 3.10. Discusión y análisis final 40 4. Conclusiones 42 5. Bibliografía 44 5.1. De carácter teórico-metodológico (fuentes secundarias) 44 5.2. General: textos sobre pop y rock 45 5.3. Específica: rock progresivo 47 ANEXO I. Relación de documentos audiovisuales de interés 50 ANEXO II. PROGROCKSAMPLER 105 2 Resumen Este trabajo, que constituye un ejercicio de periodismo cultural, en el que se han puesto en práctica conocimientos diversos adquiridos en distintas asignaturas del Grado de Periodismo, trata de definir el concepto de rock progresivo desde dos perspectivas complementarias: una interna y otra externa.