Wagner, by Ramón

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC THIS WEEK Broadcast Schedule – Spring 2020

THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC THIS WEEK Broadcast Schedule – Spring 2020 PROGRAM#: NYP 20-27 RELEASE DATE: March 25, 2020 Music of Our Time: Liang, Dalbavie, Shepherd, Muhly, and Pintscher Lei LIANG (b. 1972): Verge, for 18 Strings (2009) (Magnus Lindberg, conductor) Marc‐André DALBAVIE (b. 1961): Melodia, for Instrumental Ensemble (2009) (Magnus Lindberg, conductor) Sean SHEPHERD (b. 1979): These Particular Circumstances, in seven uninterrupted episodes (2009) (Alan Gilbert, conductor) Nico MUHLY (b. 1981): Detailed Instructions, for orchestra (2010) (Alan Gilbert, conductor) Matthias PINTSCHER (b. 1971): Songs from Solomon’s garden, for baritone and chamber orchestra (2009; New York Philharmonic Co‐Commission with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra) (Alan Gilbert, conductor; Thomas Hampson, baritone) PROGRAM#: NYP 20-28 RELEASE DATE: April 1, 2020 Bernstein Conducts Bernstein BERNSTEIN: Chichester Psalms (World Premiere performance) (Leonard Bernstein, conductor; Camerata Singers, dir. Abraham Kaplan; John Bogart, boy alto) BERNSTEIN: Kaddish, Symphony No.3 (Leonard Bernstein, conductor; Camerata Singers, dir. Abraham Kaplan; Columbus Boychoir, dir. Donald Bryant; John Bogart, boy alto; Felicia Montealegre, speaker; Jennie Tourel, mezzo-soprano) BERNSTEIN: Suites 1 and 2 from the Dybbuk (Leonard Bernstein, conductor; Paul Sperry, tenor; Bruce Fifer, bass- baritone) PROGRAM#: NYP 20-29 RELEASE DATE: April 8, 2020 American Works: Gershwin, Russo, Ellington, and Copland GERSHWIN: Porgy and Bess (selections) (recorded 1954) (André Kostelantetz, conductor) RUSSO: Symphony No. 2, “Titans” (recorded 1959) (Leonard Bernstein, conductor; Maynard Ferguson, trumpet) ELLINGTON/ Marsalis: A Tone Parallel to Harlem (recorded 1999) (Kurt Masur, conductor; Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, Wynton Marsalis, artistic director & trumpet) COPLAND: The Tender Land (abridged) (recorded 1965) (Aaron Copland, conductor; Joy Clements, soprano; Claramae Turner, mezzo-soprano; Richard Cassilly, tenor; Richard Fredricks, baritone; Norman Treigle, bass; Choral Art Society, dir. -

Alberichs Fluch

„Meiner Freiheit erster Gruß“ Alberichs Fluch (von Gunter Grimm; Dezember 2019) Alberich und die Rheintöchter Alberich ist der Herr der versklavten Zwerge, ein dämonischer Bursche, der darüber hinaus die Zau- berkunst beherrscht. Er besitzt einen Tarnhelm, der ihn unsichtbar macht, und einen magischen Ring, mit dessen Hilfe er Gold hortet und durch Erwerb und Bestechung die Weltherrschaft erringen möchte. Er ist also ein Kapitalist übler Sorte! Es versteht sich, dass Wotan sich dieses verheerende Treiben nicht gefallen lassen darf – schließlich dünkt er sich ja als Göttervater und Herr der Welt. Deshalb wogt in den vier Teilen der „Ring“-Tetralogie unentwegt der Kampf um den Ring. Im Grunde sind all die menschlichen Protagonisten der zwei Generationen: Siegmund und Sieglinde, hernach Siegfried, Gutrune und die Burgunder, nur Instrumente im Kampf um den Besitz des Ringes. Anders sieht das bei den übergeordneten Instanzen aus Götter- und Dämonenwelt: Wotan und Brünnhilde, Alberich und Hagen sind Gegenmächte – freilich nicht eindeutig als die gute und die böse Partei identifizierbar. Im ersten Teil der Tetralogie, im „Rheingold“ wird die Grundkonstellation angelegt. Die Rheintöchter besitzen das mythische Rheingold, dessen Besitz zu uneingeschränkter Macht verhilft, wenn sein Be- sitzer aus diesem Gold einen Ring schmiedet und zugleich der Liebe abschwört. Die Ausgangssituati- on ist der vergebliche Versuch des Zwergenkönigs Alberich, eine der Rheintöchter für sich zu erobern. Sie erzählen ihm vom Gold und dass derjenige, welcher der Liebe entsage, aus dem Gold einen Ring schmieden könne, der ihm quasi die Weltherrschaft verleihen würde. Das leuchtet dem Zwerg derma- ßen ein, dass er den Bericht umgehend in die Tat umsetzt. -

Temporada D'òpera 1984 -1985

GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU TEMPORADA D'ÒPERA 1984 -1985 SALOME EAU SAUVAGE EXTRÊME Christian Dior EAU DE TCHLETTE CONCBiTRÉE C-Kristian Dior PAPIS inventa Eau Sauvage Extrême Eau Sauvage Extrême: aún más intenso aún más presente aún más Eau Sauvage. GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU Temporada d'òpera 1984/85 CONSORCI OKI. GRAN TEATRE DEE LICEU (;knerali·|'\t de cataeenva aji ntament de a\rceu)na s(k:ietat del cran teatre del i.icel SAAB 900 Turbo 168: 2000 cm.'; 4 válvulas por cilindro; doble árbol de levos; intercooler y sistemo A.P.C.; 175 C.V.:5velocidodes; 210l<m/h; oceleroción de 0-100 km: 8,75sg; consumo 90km/h:7,l 1,120km/h:9,5l;troccióndelontera. A más de 200 km. por hora, el mundo combla. Por eso es indispensa¬ ble poder confiar en el vehículo que los alcance. Plenamente, como se puede confiar en un SAAB. Poraue el SAAB es un coche concebido en uno de los centros más avanzados del mundo en tecnología aeronáu¬ tico: SAAB SCANIA. Incorporando los últimos avances de su potencia tecnolágico, SAAB presenta el nuevo SAAB 900 Turbo-16, equipado con el revolucionario motor turbo de 16 vál¬ vulas e intercooler, que desarrolla 175 CV. Lo tecnología elevado o la máximo potencia, que Vd. puede comprobar en su concesionario SAAB. Personalidad en coche koÜnUc Tenor Viñas, 8 - BARCELONA- Tel: 200 73 08 m SALOMÉ Drama musical en 1 acte segons el poema homònim d'Oscar WÜde Música de Richard Strauss Dijous, 7 de febrer de 1985, a les 21 h., funció num. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1969

THE MUSIC DIRECTOR music department he organizes the vocal lenufa, Aida, Parsifal, The flying Dutch- fellows' activities, which have been much When ERICH LEINSDORF relinquishes his man, Tristan und Isolde, Elektra and Son's extended during the last two seasons. post as Music Director of the Boston Sym- Codunov, to name only a few. He now Charles Wilson becomes principal resi- phony Orchestra at the end of the 1969 lives in Hamburg. dent conductor of the New York City Berkshire Festival, he will have made a Opera Company, beginning this coming significant contribution to American mu- SHERRILL MILNES, who made his first fall. sical life. Under his leadership the Or- appearance with the Boston Symphony chestra has presented many premieres and last summer here at Tanglewood, started revived many forgotten works. Among THE SOLOISTS his professional career as a member of the latter have been the complete Schu- Margaret Hiilis's Chicago Choir, and was mann Faust, the original versions of Twenty-three year old ANDRE WATTS soon taking solo parts when the chorus Beethoven's Fidelio and Strauss's Ariadne made his debut with the Boston Sym- appeared with the Chicago Symphony. auf Naxos, and the Piano concerto no. 1 phony Orchestra last winter. He started He won scholarships to the opera depart- of Xaver Scharwenka, while among the to study the piano with his mother when ment of the Berkshire Music Center for numerous world and American premieres he was seven. Two years later he won a two consecutive summers, then joined have been works like Britten's War competition to play a Haydn concert for Boris Goldovsky's company for several requiem and Cello symphony, the piano one of the Philadelphia Orchestra chil- tours. -

18 December 2020 Page 1 of 22

Radio 3 Listings for 12 – 18 December 2020 Page 1 of 22 SATURDAY 12 DECEMBER 2020 Wolfgang Kube (oboe), Andrew Joy (horn), Rainer Jurkiewicz (horn), Rhoda Patrick (bassoon), Bernhard Forck (director) SAT 01:00 Through the Night (m000q3cy) Renaud Capuçon and Andras Schiff 04:46 AM Clara Schumann (1819-1896) Violin sonatas by Debussy, Schumann and Franck recorded at 4 Pieces fugitives for piano, Op 15 the Verbier Festival. Catriona Young presents. Angela Cheng (piano) 01:01 AM 05:01 AM Claude Debussy (1862-1918) Jozef Elsner (1769-1854) Violin Sonata in G minor, L 140 Echo w leise (Overture) Renaud Capuçon (violin), Andras Schiff (piano) Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Andrzej Straszynski (conductor) 01:14 AM Robert Schumann (1810-1856) 05:07 AM Violin Sonata No 2 in D minor, Op 121 Vitazoslav Kubicka (1953-) Renaud Capuçon (violin), Andras Schiff (piano) Winter Stories from the Forest, op 251, symphonic suite Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra, Adrian Kokos (conductor) 01:46 AM Cesar Franck (1822-1890) 05:21 AM Violin Sonata in A Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924) Renaud Capuçon (violin), Andras Schiff (piano) Seven Elegies (No 2, All' Italia) Valerie Tryon (piano) 02:15 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) 05:29 AM Adagio, from 'Violin Sonata No 33 in E flat, K 481' (encore) Vitezslav Novak (1870-1949) Renaud Capuçon (violin), Andras Schiff (piano) V Tatrach (In the Tatra mountains) - symphonic poem (Op.26) BBC National Orchestra of Wales, Richard Hickox (conductor) 02:23 AM Sergey Prokofiev (1891-1953) 05:46 AM Symphony No 3 in C minor, Op 44 Igor Stravinsky (1882 - 1971) Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Riccardo Chailly (conductor) Concertino for string quartet Apollon Musagete Quartet 03:01 AM Dora Pejacevic (1885-1923) 05:53 AM Symphony No 1 in F sharp minor, Op 41 Thomas Kessler (b.1937) Croatian Radio and Television Symphony Orchestra, Mladen Lost Paradise Tarbuk (conductor) Camerata Variabile Basel 03:46 AM 06:08 AM John Browne (fl.1490) Bela Bartok (1881-1945), Arthur Willner (arranger) O Maria salvatoris mater (a 8) Romanian folk dances (Sz.56) arr. -

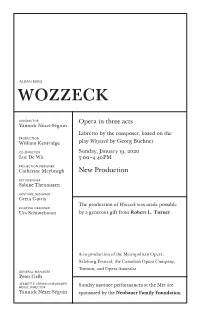

January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM

ALBAN BERG wozzeck conductor Opera in three acts Yannick Nézet-Séguin Libretto by the composer, based on the production William Kentridge play Woyzeck by Georg Büchner co-director Sunday, January 19, 2020 Luc De Wit 3:00–4:40 PM projection designer Catherine Meyburgh New Production set designer Sabine Theunissen costume designer Greta Goiris The production of Wozzeck was made possible lighting designer Urs Schönebaum by a generous gift from Robert L. Turner A co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; Salzburg Festival; the Canadian Opera Company, Toronto; and Opera Australia general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Sunday matinee performances at the Met are Yannick Nézet-Séguin sponsored by the Neubauer Family Foundation 2019–20 SEASON The 75th Metropolitan Opera performance of ALBAN BERG’S wozzeck conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin in order of vocal appearance the captain the fool Gerhard Siegel Brenton Ryan wozzeck a soldier Peter Mattei Daniel Clark Smith andres a townsman Andrew Staples Gregory Warren marie marie’s child Elza van den Heever Eliot Flowers margret Tamara Mumford* puppeteers Andrea Fabi the doctor Gwyneth E. Larsen Christian Van Horn ac tors the drum- major Frank Colardo Christopher Ventris Tina Mitchell apprentices Wozzeck is stage piano solo Richard Bernstein presented without Jonathan C. Kelly Miles Mykkanen intermission. Sunday, January 19, 2020, 3:00–4:40PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA A scene from Chorus Master Donald Palumbo Berg’s Wozzeck Video Control Kim Gunning Assistant Video Editor Snezana Marovic Musical Preparation Caren Levine*, Jonathan C. Kelly, Patrick Furrer, Bryan Wagorn*, and Zalman Kelber* Assistant Stage Directors Gregory Keller, Sarah Ina Meyers, and J. -

The Following Great Artists Have Taught

The following great artists have performed, taught, and/or studied at Hidden Valley Ansel Adams Rod Gilfry Pepe Romero Photographer Baritone Guitarist Sir Thomas Allen Philip Glass Jenny Penny Baritone Composer/Pianist Principal Dancer, The Royal Ballet Julius Baker Thomas Hampson Claudette Peterson Principal Flute, New York Philharmonic Baritone Soprano Samuel Barber Gary Hines Cindy Phelps Composer Conductor, Sounds of Blackness Principal Violist, New York Philharmonic Jeanne Baxtresser Sue Hinshaw Gregor Piatigorsky Principal Flute, New York Philharmonic Soprano Cellist Randall Behr Henry Holt Paul Polivnik Conductor/Pianist Conductor Conductor Martin Bernheimer Reg Huston Margarite Porter Music Critic Bass-Baritone Principal Dancer, The Royal Ballet Roger Cantrell Eugene Izotov Jean-Pierre Rampal Conductor Principal Oboist, San Francisco Symphony Flutist Colin Carr James Jarrett Stewart Robertson Celloist Author/Aesthetist Conductor Richard Cassilly Graham Johnson Joe Robinson Tenor Pianist Principal Oboe, New York Philharmonic David Conte Emil Khudyev Neil Rosenshein Composer Associate Principal Clarinet, Seattle Sym- Tenor Ronald Cunningham phony Ali Ryerson Choreographer, The Boston Ballet Farkhad Khudyev Jazz Flutist Robert Darling Conductor,/Violinist Charles Schleuter Designer/Director Mark Kosower Principal Trumpet, Boston Symphony Or- Leonard Davis Principal Cello, The Cleveland Orchestra chestra Principal Violist, New York Philharmonic Louis Lebherz Elisabeth Schwarzkopf Warren Deck Bass Soprano Principal Tuba, New York Philharmonic -

Lost in the Stars

REVIEWS Performances Lost in the Stars Washington National Opera and the production rocked the house. In musical terms, the 2016 version is even stronger, especially 12–20 February 2016 the contributions of the orchestra, due in great part to the added forces supplied by the Kennedy Center and WNO, particularly the dark richness of added violas. Conductor John DeMain’s Kurt Weill and Maxwell Anderson’s Lost in the Stars sailed into authoritative command of Weill’s score brought the powerful the Kennedy Center this February captained by Washington music to the forefront. National Opera’s Artistic Director Francesca Zambello. The The sound of the men in the Chorus reminds me of the production was an important event in the nation’s capital, not powerful South African tradition of male ensembles, rooted in only amplifying pressing conversations about race and unequal the practice of corralling Black miners in stockades, with music justice but broadening an artistic question in what has become their only emotional outlet. Through the choral writing, the a rich musical-theater nexus—what is musical theater? Lost nation itself becomes a character, with the first act establishing the in the Stars has been a challenge to define since it debuted on context and letting music invoke the work’s panoramic feel and Broadway, where it met mixed critical response. It has continued grand themes. The audience is challenged to feel the loneliness of to perplex many critics who try ungraciously to fit it into a pre- living in fear of “the other,” and to consider how fear and greed existing genre. -

Summer 2008 Dess’ Stiller Frieden Dich Umfing? Volume 5, Number 3 —Parsifal

Wagneriana Du konntest morden? Hier im heil’gen Walde, Summer 2008 dess’ stiller Frieden dich umfing? Volume 5, Number 3 —Parsifal From the Editor he Boston Wagner Society will turn five on September 20. We are planning some festivities for that day that will include live music. This special event will be open to members and their guests only. Invitations will be forthcom- T ing. This year we have put in place new policies for applying for tickets to the Bayreuth Festival. Before you send in your application for 2009, please make sure that you have read these policies (see page 7). Here is a sneak preview of the next season’s events: a talk by William Berger, co-host of Sirius Met Opera’s live broad- casts and author of Wagner without Fear: Learning to Love–and Even Enjoy–Opera’s Most Demanding Genius (on October 18); a talk by Professor Robert Bailey, a well-known Wagnerian scholar and the author of numerous articles on Wagner, titled “Wagner’s Beguiling Tristan und Isolde and Its Misunderstood Aspects” (on November 15); an audiovisual presentation comparing the Nibelungenlied with Wagner’s Ring Cycle, by Vice President Erika Reitshamer (winter 2009). We will add more programs as needed. Due to space limitations, in this issue we are omitting part 4 of Paul Heise’s article “The Influence of Feuerbach on the Libretto of Parsifal.” The series will resume in the next issue. –Dalia Geffen, President and Founder Wagner from a Buddhist Perspective Paul Schofield, The Redeemer Reborn: Parsifal as the Fifth Opera of Wagner’s Ring (New York: Amadeus Press, 2007) he Redeemer Reborn is a very important book. -

The Following Great Artists Have Performed, Taught, And/Or Studied at Hidden Valley

The following great artists have performed, taught, and/or studied at Hidden Valley Ansel Adams Rod Gilfrey Pepe Romero Photographer Baritone Guitarist Sir Thomas Allen Philip Glass Jenny Penny Baritone Composer/Pianist Principal Dancer, The Royal Ballet Julius Baker Thomas Hampson Claudette Peterson Principal Flute, New York Philharmonic Baritone Soprano Samuel Barber Gary Hines Cindy Phelps Composer Conductor, Sounds of Blackness Principal Violist, New York Philharmonic Jeanne Baxtresser Sue Hinshaw Gregor Piatigorsky Principal Flute, New York Philharmonic Soprano Cellist Randall Behr Henry Holt Paul Polivnik Conductor/Pianist Conductor Conductor Martin Bernheimer Reg Huston Margarite Porter Music Critic Bass-Baritone Principal Dancer, The Royal Ballet Roger Cantrell Eugene Izotov Jean-Pierre Rampal Conductor Principal Oboist, San Francisco Symphony Flutist Colin Carr James Jarrett Stewart Robertson Celloist Author/Aesthetist Conductor Richard Cassilly Graham Johnson Joe Robinson Tenor Pianist Principal Oboe, New York Philharmonic David Conte Emil Khudyev Neil Rosenshein Composer Associate Principal Clarinet, Seattle Sym- Tenor Ronald Cunningham phony Ali Ryerson Choreographer, The Boston Ballet Farkhad Khudyev Jazz Flutist Robert Darling Conductor,/Violinist Charles Schleuter Designer/Director Mark Kosower Principal Trumpet, Boston Symphony Or- Leonard Davis Principal Cello, The Cleveland Orchestra chestra Principal Violist, New York Philharmonic Louis Lebherz Elisabeth Schwarzkopf Warren Deck Bass Soprano Principal Tuba, New York -

In Memoriam: Ekkehard Wlaschiha (1938-2019)

In memoriam: Ekkehard Wlaschiha (1938-2019) Foto © YouTube Den tyske baryton- och Wagnersångaren Ekkehard Wlaschiha, en av de gedigna sångarna av den gamla DDR-stammen, har avlidit i en ålder av 80 år. Wlaschiha föddes i Pirna i Sachsen den 28 maj 1938 och studerade vid Franz Liszt- akademien i Weimar innan debuten vid Thüringisches Landestheater i Gera som Dr. Cajus i Muntra fruarna i Windsor 1961. Under 1960-talet var han verksam i Dresden och Weimar innan han blev medlem av ensemblen vid operahuset i Leipzig 1970 till 1983. Han sjöng som ständig gäst vid Dresdner Staatsoper och gästspelade i Sofia och Leningrad. Höjdpunkter var bl.a. dramatiska barytonpartier som Scarpia i Tosca, Pizarro i Fidelio, Tonio i Pajazzo, Coppelius i Hoffmanns äventyr och Jochanaan i Salome. Sedan 1982 var han medlem av ensemblen vid Staatsoper Berlin varifrån hans stora internationella karriär som Wagnersångare inleddes. Wlaschiha medverkade även som Kurwenal i Tristan och Isolde vid festivalen i Lausanne 1983. Den 13 februari 1985 sjöng han Kaspar i Webers Friskytten vid återinvigningen av den bombade Semper-operan i Dresden. Vid festspelen i Bayreuth sjöng han för första gången som Kurwenal 1986 under Daniel Barenboim, 1987-91 och 1993 som Telramund i Lohengrin, 1994-96 och 1997-98 som Alberich iNibelungens Ring. 1987 hade han dessutom stor framgång som Jochanaan mot Hildegard Behrens Salome i München. 1988 debuterade Wlaschiha på Covent Garden som Alberich, en roll som även förde honom till Metropolitan året därpå. 1991 kunde man höra honom som Amfortas i Parsifal på Met liksom Klingsor i samma opera 2001.