The Neapolitan Francesco Fontana Inventor of the Astronomical Telescope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revised Final MASTERS THESIS

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Carlo Fontana and the Origins of the Architectural Monograph A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Juliann Rose Walker June 2016 Thesis Committee: Dr. Kristoffer Neville, Chairperson Dr. Jeanette Kohl Dr. Conrad Rudolph Copyright by Juliann Walker 2016 The Thesis of Juliann Rose Walker is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements I would first like to start by thanking my committee members. Thank you to my advisor, Kristoffer Neville, who has worked with me for almost four years now as both an undergrad and graduate student; this project was possible because of you. To Jeanette Kohl, who was integral in helping me to outline and finish my first chapter, which made the rest of my thesis writing much easier in comparison. Your constructive comments were instrumental to the clarity and depth of my research, so thank you. And thank you to Conrad Rudolph, for your stern, yet fair, critiques of my writing, which were an invaluable reminder that you can never proofread enough. A special thank you to Malcolm Baker, who offered so much of his time and energy to me in my undergraduate career, and for being a valuable and vast resource of knowledge on early modern European artwork as I researched possible thesis topics. And the warmest of thanks to Alesha Jeanette, who has always left her door open for me to come and talk about anything that was on my mind. I would also like to thank Leigh Gleason at the California Museum of Photography, for giving me the opportunity to intern in collections. -

The Evolution of the Early Refractor 1608 - 1683

The Evolution of the Early Refractor 1608 - 1683 Chris Lord Brayebrook Observatory 2012 Summary The optical workings of the refracting telescope were very poorly understood during the period 1608 thru' the early 1640's, even amongst the cogniscenti. Kepler wrote Dioptrice in the late summer of 1610, but it was not published until a year later, and was not widely read or understood. Lens grinding and polishing techniques traditionally used by spectacle makers were inadequate for manufacturing telescope objectives. Following the pioneering optical work of John Burchard von Schyrle, the artisanship of Johannes Wiesel, and the ingenuity of the Huyghens brothers Constantijn and Christiaan, the refracting telescope was improved sufficiently for resolution limited by atmospheric seeing to be obtained. Not until the phenomenon of dispersion was explained by Isaac Newton could the optical error chromatic aberration be understood. Nevertheless Christiaan Huyghens did design an eyepiece which corrected lateral chromatic aberration, although the theory of his eyepiece was not made known until 1667, and particulars published posthumously in 1703. Introduction This purpose of this paper is to draw together the key elements in the development of the early refractor from 1608 until the early 1680's. During this period grinding and polishing methods of object glasses improved, and several different multi-lens eyepiece arrangements were invented. Those curious about the progress of telescope technology during the C17th, be they researchers, collectors, may find this paper useful. The emergence of the refracting telescope in 1608, so simple a device that it could easily be copied, in all likelyhood had its origins almost two decades beforehand. -

Galileo in Early Modern Denmark, 1600-1650

1 Galileo in early modern Denmark, 1600-1650 Helge Kragh Abstract: The scientific revolution in the first half of the seventeenth century, pioneered by figures such as Harvey, Galileo, Gassendi, Kepler and Descartes, was disseminated to the northernmost countries in Europe with considerable delay. In this essay I examine how and when Galileo’s new ideas in physics and astronomy became known in Denmark, and I compare the reception with the one in Sweden. It turns out that Galileo was almost exclusively known for his sensational use of the telescope to unravel the secrets of the heavens, meaning that he was predominantly seen as an astronomical innovator and advocate of the Copernican world system. Danish astronomy at the time was however based on Tycho Brahe’s view of the universe and therefore hostile to Copernican and, by implication, Galilean cosmology. Although Galileo’s telescope attracted much attention, it took about thirty years until a Danish astronomer actually used the instrument for observations. By the 1640s Galileo was generally admired for his astronomical discoveries, but no one in Denmark drew the consequence that the dogma of the central Earth, a fundamental feature of the Tychonian world picture, was therefore incorrect. 1. Introduction In the early 1940s the Swedish scholar Henrik Sandblad (1912-1992), later a professor of history of science and ideas at the University of Gothenburg, published a series of works in which he examined in detail the reception of Copernicanism in Sweden [Sandblad 1943; Sandblad 1944-1945]. Apart from a later summary account [Sandblad 1972], this investigation was published in Swedish and hence not accessible to most readers outside Scandinavia. -

THE STUDY of SATURN's RINGS 1 Thesis Presented for the Degree Of

1 THE STUDY OF SATURN'S RINGS 1610-1675, Thesis presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Field of History of Science by Albert Van Haden Department of History of Science and Technology Imperial College of Science and Teohnology University of London May, 1970 2 ABSTRACT Shortly after the publication of his Starry Messenger, Galileo observed the planet Saturn for the first time through a telescope. To his surprise he discovered that the planet does.not exhibit a single disc, as all other planets do, but rather a central disc flanked by two smaller ones. In the following years, Galileo found that Sa- turn sometimes also appears without these lateral discs, and at other times with handle-like appendages istead of round discs. These ap- pearances posed a great problem to scientists, and this problem was not solved until 1656, while the solution was not fully accepted until about 1670. This thesis traces the problem of Saturn, from its initial form- ulation, through the period of gathering information, to the final stage in which theories were proposed, ending with the acceptance of one of these theories: the ring-theory of Christiaan Huygens. Although the improvement of the telescope had great bearing on the problem of Saturn, and is dealt with to some extent, many other factors were in- volved in the solution of the problem. It was as much a perceptual problem as a technical problem of telescopes, and the mental processes that led Huygens to its solution were symptomatic of the state of science in the 1650's and would have been out of place and perhaps impossible before Descartes. -

On the Alleged Use of Keplerian Telescopes in Naples in the 1610S

On the Alleged Use of Keplerian Telescopes in Naples in the 1610s By Paolo Del Santo Museo Galileo: Institute and Museum of History of Science – Florence (Italy) Abstract The alleged use of Keplerian telescopes by Fabio Colonna (c. 1567 – 1640), in Naples, since as early as October 1614, as claimed in some recent papers, is shown to be in fact untenable and due to a misconception. At the 37th Annual Conference of the Società Italiana degli Storici della Fisica e dell'Astronomia (Italian Society of the Historians of Physics and Astronomy, SISFA), held in Bari in September 2017, Mauro Gargano gave a talk entitled Della Porta, Colonna e Fontana e le prime osservazioni astronomiche a Napoli. This contribution, which appeared in the Proceedings of the Conference (Gargano, 2019a), was then followed by a paper —actually, very close to the former, which, in turn, is very close to a previous one (Gargano, 2017)— published, in the same year, in the Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage (Gargano, 2019b). In both of these writings, Gargano claimed that the Neapolitan naturalist Fabio Colonna (c. 1567 – 1640), member of the Accademia dei Lincei, would have made observations with a so-called “Keplerian” or “astronomical” telescope (i.e. with converging eyepiece), in the early autumn of 1614. The events related to the birth and development of Keplerian telescope —named after Johannes Kepler, who theorised this optical configuration in his Dioptrice, published in 1611— are complex and not well-documented, and their examination lies beyond the scope of this paper. However, from a historiographical point of view, the news that someone was already using such a configuration since as early as autumn 1614 for astronomical observations, if true, would have not negligible implications, which Gargano himself does not seem to realize. -

X9056 E-Mail: [email protected]

Welcome to ENGN1560 Applied Electromagnetics OPTICS Prof. Daniel Mittleman Office: B&H 228 Phone: x9056 E-mail: [email protected] Office hours: Thursdays, 1:00-2:30pm The science of LIGHT All assignments and important class information: https://www.brown.edu/research/labs/mittleman/engn-1560-spring-2017 NOTE: there will be no printed handouts. Logistics • Lectures: MWF@noon • Problem sets: weekly (mostly) • Office Hours: Thursdays 1:00-2:30pm (or by appointment) • Exams: two oral midterms, one written final • Text book: Optics, by Eugene Hecht (4th ed.) • Handouts / Announcements: online only • Lecture attendance: strongly recommended 1. Optics: An Introduction A few of the key questions that have motivated optics research throughout history A short, arbitrary, condensed history of optics Maxwell's Equations Cool things that involve light Total internal reflection Interference Diffraction The Laser Nonlinear Optics Ultrafast Optics Optics: A few key motivating questions 1. What is the speed of light? Is it infinitely fast? If not, then how do we measure its speed? 2. What is light? Is it a wave, or is it a stream of particles? There is a big difference in the behavior of particles vs. waves. What do we mean by “particle” and “wave”? When speaking of a flow of particles, it is clear that something with a mass (greater than zero) is moving: PmV Bullets carry momentum. Also, they can’t be subdivided: Half a bullet doesn’t work. For waves, it is clear that energy moves along one direction. But there is no net flow of mass. Also, a wave can be shrunk arbitrarily and it’s still a wave - there is no “smallest size”. -

Francesco Fontana and the Birth of the Astronomical Telescope

Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage, 20(2), 271‒288 (2017). FRANCESCO FONTANA AND THE BIRTH OF THE ASTRONOMICAL TELESCOPE Paolo Molaro INAF, Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste, Via G.B. Tiepolo 11, 34143 Trieste, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: In the late 1620s the Neapolitan Francesco Fontana was the first to observe the sky using a telescope with two convex lenses, which he had manufactured himself. Fontana succeeded in drawing the most accurate maps of the Moon’s surface of his time, which were to become popular through a number of publications that appeared throughout Europe but did not acknowledge the author. At the end of 1645, in a state of declining health and pressed by the need to defend his authorship, Fontana carried out an intense observing campaign, the results of which he hurriedly collected in his Novae Coelestium Terrestriumque rerum Observationis (1646), the only public- cation he left for posterity. Fontana observed the Moon’s main craters, such as Tycho (which he referred to as ‘Fons Major’), their radial debris patterns and changes in their appearance due to the Moon’s motion. He observed the gibbosity of Mars at quadrature and, together with the Jesuit Giovanni Battista Zupus, he described the phases of Mercury. Fontana observed the two—and occasionally three—major bands of Jupiter, and inferred the rotation of the major planets Mars, Jupiter and Saturn, arguing that they could not be attached to an Aristotelian sky. He came close to revealing the ring structure of Saturn. He also suggested the presence of additional moons around Jupiter, Venus and Saturn, which prompted a debate that lasted more than a hundred years. -

Galileo's World Reprise, Jan-Feb 2017 Art and Astronomy Walking Tour

Galileo’s World Reprise, Jan-Feb 2017 Art and Astronomy Walking Tour What was it like to be an astronomer when art and mathematics were galileo.ou.edu oulynx.org intertwined? Exhibit Locations: “SE HALL” contains The Sky at Night reprise gallery. “S HALL” contains the New Physics gallery and the Rotating Display. Refer to the Exhibit Guide for a fuller description of any book or instrument listed below, keyed to its Gallery name and object number. Ask for an iPad at the Welcome Desk or download a free copy of the Exhibit Guide from the iBooks Store; requires the free iBooks app (iOS or Mac). Follow oulynx.com for exhibit-based open educational resources (OERs). Gallery: Galileo and the Telescope 1. Galileo, Sidereus nuncius (Venice, 1610), “Starry Messenger.” SE HALL In the Starry Messenger (1610), Galileo published the first observations of the heavens made with the telescope. His report caused a sensation, as he claimed to discover mountains on the Moon, vast numbers of previously undetected stars and four satellites of Jupiter. Galileo reported that the planet Jupiter moves through the heavens without leaving its satellites behind. The Earth and Moon both have mountains, seas, atmospheres, and both shine by reflected light. All of these discoveries might suggest that the Earth, also, is a wandering planet. 3. Giorgio Vasari, Le opere (Florence, 1878-85), 8 vols. SE HALL Galileo’s scientific discoveries occurred in the context of a specific artistic culture which possessed sophisticated mathematical techniques for drawing with linear perspective and handling light and shadow. (See “Interdisciplinary connections,” last page.) 8. -

Mapping the Planet Mars by Philip Corneille

Planetary exploration Spaceflight Vol 47 July 2005 Mapping the planet Mars by Philip Corneille Ancient Babylonian clay tablets depicted the Earth as a flat circular disk but both Roman, Greek and Arab empires’ cartographers were more interested in producing celestial globes rather than terrestrial. The first terrestrial globe was produced by Crates of Mallos, around 150 BC, and the earliest surviving Earth globe was produced by Martin Behaim in 1492. However, it lasted until the 20th century when the first photos of Earth from space to produce the most accurate terrestrial globes. Since then mankind’s attention has turned to the planets. Mars before the space age The planet Mars, named after the Roman god of war, is fourth in order of distance from the Sun and seventh in order of size and mass. The astronomical symbol for Mars, represents a shield with a spear. The so- called red planet is slightly more than half the size of Earth but the lack of oceans gives it the same landmass as Earth. Mars has no Lowell observatory – Flagstaff Arizona plate motion and its rotational axis is inclined to the ecliptic, like Earth’s. The planet Mars globe (top) made by completes an elliptical orbit around the Sun Percival Lowell in 1911, in 687 days and spins on its axis with a based on his observations. It period of 24 hours 37 minutes. This period is shows the ‘canals’ in the named a ‘sol’ or Martian solar day. It has two area of Elysium planitia and moons, Phobos (Fear) and Deimos (Terror), Utopia planitia and (above) named after the mythical chariot horses of Mars photo-frames show the Mars. -

Venusians: the Planet Venus in the 18Th-Century Extraterrestrial Life Debate

MEETING VENUS C. Sterken, P. P. Aspaas (Eds.) The Journal of Astronomical Data 19, 1, 2013 Venusians: the Planet Venus in the 18th-Century Extraterrestrial Life Debate David Dun´er1,2 1History of Science and Ideas, Lund University, Biskopsgatan 7, 223 62 Lund, Sweden 2Centre for Cognitive Semiotics, Lund University, Sweden Abstract. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries it became possible to believe in the existence of life on other planets on scientific grounds. Once the Earth was no longer the center of the universe according to Copernicus, once Galileo had aimed his telescope at the Moon and found it a rough globe with mountains and seas, the assumption of life on other planets became much less far-fetched. In general there were no actual differences between Earth and Venus, since both planets orbited the Sun, were of similar size, and possessed mountains and an atmosphere. If there is life on Earth, one may ponder why it could not also exist on Venus. In the extraterrestrial life debate of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the Moon, our closest celestial body, was the prime candidate for life on other worlds, although a number of scientists and scholars also speculated about life on Venus and on other planets, both within our solar system and beyond its frontiers. This chapter discusses the arguments for life on Venus and those scientific findings that were used to support them, which were based in particular on assumptions and claims that both mountains and an atmosphere had been found on Venus. The transits of Venus in the 1760s became especially important for the notion that life could thrive on Venus. -

Michiel Florent Van Langren and Lunar Naming Peter Van Der Krogt, Ferjan Ormeling

ONOMÀSTICA BIBLIOTECA TÈCNICA DE POLÍTICA LINGÜÍSTICA Michiel Florent van Langren and Lunar Naming Peter van der Krogt, Ferjan Ormeling DOI: 10.2436/15.8040.01.190 Abstract Michiel Florent van Langren produced a lunar map in 1645 in order to present a way to mariners to find their position at sea by observing which craters were either illuminated by solar rays or obscured during the waxing or waning of the moon. This required a detailed map of the moon and in order to be able to refer to lunar objects these had to be named. The lunar map he produced in 1645 bore over 300 names, following the system of subdividing lunar topography into land masses and seas (a distinction based on Plutarch), and craters or peaks. He is therefore the pioneer of both selenography and selenonymy. His nomenclature had no lasting impact, although some 50 names he introduced are still used for other craters. The same negative result was obtained by Johannes Hevelius who introduced in 1647 his own naming system based on geographical names. It was the nomenclature proposed by a third astronomer, Giovanni Riccioli, shown on his lunar map produced in 1651 that won the day. From the 244 names Riccioli proposed on his lunar map, 201 are still in use. Nevertheless, despite Van Langren’s lack of success, from a toponymical point of view his methodology is interesting as it provides insight into the contemporary world view of a seventeenth century scientist who was dependant on sponsors to allow him to carry out his work and transform his theories into practical instructions. -

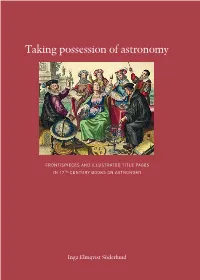

Taking Possession of Astronomy It Noteworthy

ABSTRACT Inga Elmqvist Söderlund possession of astronomy Taking The frontispieces and illustrated title pages in books on astronomy of the 17th century are beautiful works of art. They show a wide variety of designs, each pointing out the particularity of the title and what makes Taking possession of astronomy it noteworthy. The thesis is a survey of 291 frontispieces and illustrated title pages in European books on astronomy from the 17th century. It is a quantitative and qualitative survey of how motifs are related to consumption, identification and display. Elements in the motifs related to factual content as opposed to those aimed to raise the perceived value of astronomy are distinguished. The quantitative study shows that astronomical phenomena (90 per The author Inga Elmqvist Söderlund was born cent) and scientific instruments (62 per cent, or as much as 86 per cent if in 1967. She holds a degree of Master of Arts only titles with illustrations occupying an entire page are considered) are with a major in the History of Art (Stockholm the most common motifs to inform the reader of the genre. Besides these, University 2001) and a degree of MSc in Business a wide range of depicted features indicate the particularity of each title. Administration and Economics (Lund University Different means for raising the value of astronomy and its attributes are 1993). She has curated several exhibitions and held posts at various museums in Sweden. Since identified. The interplay of “real” or “credible” elements with fictional 1996 she has been Curator at the Observatory ones was used to attract attention, create positive associations and Museum in Stockholm.