Academic Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Assaf Report on Research Publishing in and from South Africa (2018)

Twelve Years Later: Second ASSAf Report on Research Publishing in and from South Africa (2018) Applying scientific thinking in the service of society PO Box 72135, Lynnwood Ridge 0040, Pretoria, South Africa Tel: +27 12 349 6600 • Fax: +27 86 576 9520 • Email: [email protected] Department: Department: Science and Technology Science and Technology TWELVE YEARS LATER Academy of Science of South Africa December 2018 ISBN 978-0-6399410-5-9 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/assaf.2018/0030 Cite: Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf), (2019). Twelve Years Later: Second ASSAf Report on Research Publishing In and From South Africa (2018). [Online] Available at: DOI:10.17159/assaf.2018/0030 Published by: Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf) PO Box 72135, Lynnwood Ridge, Pretoria, South Africa, 0040 Tel: +27 12 349 6600 • Fax: +27 86 576 9520 E-mail: [email protected] Reproduction is permitted, provided the source and publisher are appropriately acknowledged. The Academy of Science of South Africa (ASSAf) was inaugurated in May 1996. It was formed in response to the need for an Academy of Science consonant with the dawn of democracy in South Africa: activist in its mission of using science and scholarship for the benefit of society, with a mandate encompassing all scholarly disciplines that use an open-minded and evidence-based approach to build knowledge. ASSAf thus adopted in its name the term ‘science’ in the singular as reflecting a common way of enquiring rather than an aggregation of different disciplines. Its Members are elected on the basis of a combination of two principal criteria, academic excellence and significant contributions to society. -

DHET Local Journals (2021)

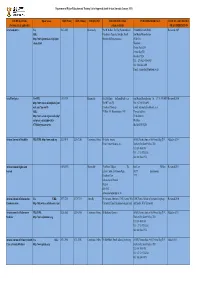

Department of Higher Education and Training List of Approved South African Journals (January 2021) JOURNAL TITLE Open Access ISSN (Print) ISSN (Online) FREQUENCY EDITOR'S DETAILS PUBLISHER'S DETAILS DATE OF LAST REVIEW (Previous title if applicable) (when available) OR ACCREDITATION Acta Academica Yes 0587-2405 Bi-annually Prof H Melber, The Dag Hammarskjold PUBLISHER ADDRESS Reviewed 2009 URL: Foundation Uppsala, Sweden, Email: Sun Media Bloemfontein http://www.journals.co.za/ej/ejour_ [email protected] 55 Brill St classic.html Westdene Postnet Suite 214 Private Bag X01 Brandhof 9324 Tel : +27-(0)51-430-0459 Fax : 086-545-4491 E-mail : [email protected] Acta Theologica Yes URL: 1015-8758 Biannually Dr L Hoffman [email protected] Sun Media Bloemfontein Tel: + 27 51 430 0459 Reviewed 2010 http://www.ufs.ac.za/templates/jour Prof HC van Zyl Fax: +27 86 545 4491 nals.aspx?journal=5 Faculty of Theology E-mail: [email protected] URL: PO Box 339, Bloemfontein,9300 Physical address: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php? 59 Brill Street script=sci_serial&pid=1015- Westdene 8758&lng=en&nrm=iso BLOEMFONTEIN African Journal of Disability YES, URL: http://www.ajod.org 2223-9170 2226-7220 Continuous Online Dr Leslie Swartz AOSIS, Postnet Suite #110, Private Bag X19, Added in 2014 Email: [email protected] Durbanville, South Africa, 7551 Tel: 086 1000 381 Tel: +27 21 975 2602 Fax: 086 5004 974 African Human Rights Law 1609-073X Biannually Prof Frans Viljoen The Juta Law PO Box Reviewed 2011 Journal Editor: Centre for Human Right 24299 -

Stronger Together

STRONGER TOGETHER supporting, giving to, and investing in Wits STRONGERTOGETHER WITSVICE-CHANCELLOR As you are aware, we are facing challenging times, when public funding for higher education is declining, while students demand no fee increases or no fees at all. Universities are caught in a financial pincer, which we have to transcend without compromising academic quality. We are increasingly reliant on your support to attract and retain talented, innovative academics and students; to offer more scholarships to disadvantaged students with academic potential; to support the research and teaching activities of our university; to update our technology and equipment; and to maintain and develop our facilities and infrastructure. Your support assists us in ensuring that Wits remains financially sustainable and at the cutting edge of higher education on the continent and globally. Your support also boosts us in our You, our donors, supporters critical role of helping to build a strong, stable, democratic, and investors, are the internationalised society in a country dealing with profound mainsail of our university. socio-political problems, unemployment and complex issues of You have consistently been decolonisation and transformation. there for us, helping to sustain We are currently required to make hard financial trade-offs that and advance our globally are not simply managerial and strategic; they are also ethical competitive university. and moral. They include being firm about keeping campus safe and functioning, while proactively addressing inequality in South African society, contributing to job creation and overcoming the capacity constraints that are limiting Africa’s economic growth. In so many ways, Wits has an inestimable role to play in shaping the future of South Africa and the continent. -

Commission of Inquiry Into Higher Education Report

REPORT OF THE COMMISSION OF ENQUIRY INTO HIGHER EDUCATION AND TRAINING TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 9 1.1 The start of the #Feesmustfall protest: the demands and the outcome ............................................................................................................ 9 1.2 The students’ demands .................................................................... 16 1.3 The consequences of the protest and determined increases ........... 20 2 The Mandate of the Commission .................................................................. 26 3 Higher Education and Training: Purpose, Policy and Historical Development and Funding ............................................................................. 32 3.1 The purpose of higher education ...................................................... 32 3.2 Higher education policy .................................................................... 34 3.3 The National Development Plan (NDP) ............................................ 36 3.4 The White Paper for Post-School Education and Training (PSET) (2013) ............................................................................................... 38 3.5 Early policy decisions on university funding ..................................... 39 3.6 Public or private benefit .................................................................... 42 3.7 Defining higher education and training for