Are BGP Routers Open to Attack? an Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Well-Known TCP Port Numbers Page 1 of 2

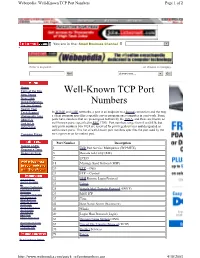

Webopedia: Well-Known TCP Port Numbers Page 1 of 2 You are in the: Small Business Channel Jump to Website Enter a keyword... ...or choose a category. Go! choose one... Go! Home Term of the Day Well-Known TCP Port New Terms New Links Quick Reference Numbers Did You Know? Search Tool Tech Support In TCP/IP and UDP networks, a port is an endpoint to a logical connection and the way Webopedia Jobs a client program specifies a specific server program on a computer in a network. Some About Us ports have numbers that are preassigned to them by the IANA, and these are known as Link to Us well-known ports (specified in RFC 1700). Port numbers range from 0 to 65536, but Advertising only ports numbers 0 to 1024 are reserved for privileged services and designated as well-known ports. This list of well-known port numbers specifies the port used by the Compare Prices server process as its contact port. Port Number Description Submit a URL 1 TCP Port Service Multiplexer (TCPMUX) Request a Term Report an Error 5 Remote Job Entry (RJE) 7 ECHO 18 Message Send Protocol (MSP) 20 FTP -- Data 21 FTP -- Control Internet News 22 SSH Remote Login Protocol Internet Investing IT 23 Telnet Windows Technology Linux/Open Source 25 Simple Mail Transfer Protocol (SMTP) Developer Interactive Marketing 29 MSG ICP xSP Resources Small Business 37 Time Wireless Internet Downloads 42 Host Name Server (Nameserv) Internet Resources Internet Lists 43 WhoIs International EarthWeb 49 Login Host Protocol (Login) Career Resources 53 Domain Name System (DNS) Search internet.com Advertising -

NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack 1.0

NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack 1.0 Americas Headquarters Cisco Systems, Inc. 170 West Tasman Drive San Jose, CA 95134-1706 USA http://www.cisco.com Tel: 408 526-4000 800 553-NETS (6387) Fax: 408 527-0883 © 2013 Cisco Systems, Inc. All rights reserved. CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Release Notes for NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack 1.0 1 CHAPTER 2 BGP 3 BITTORRENT 6 CITRIX 7 DHCP 8 DIRECTCONNECT 9 DNS 10 EDONKEY 11 EGP 12 EIGRP 13 EXCHANGE 14 FASTTRACK 15 FINGER 16 FTP 17 GNUTELLA 18 GOPHER 19 GRE 20 H323 21 HTTP 22 ICMP 23 IMAP 24 IPINIP 25 IPV6-ICMP 26 IRC 27 KAZAA2 28 KERBEROS 29 L2TP 30 NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack 1.0 iii Contents LDAP 31 MGCP 32 NETBIOS 33 NETSHOW 34 NFS 35 NNTP 36 NOTES 37 NTP 38 OSPF 39 POP3 40 PPTP 41 PRINTER 42 RIP 43 RTCP 44 RTP 45 RTSP 46 SAP 47 SECURE-FTP 48 SECURE-HTTP 49 SECURE-IMAP 50 SECURE-IRC 51 SECURE-LDAP 52 SECURE-NNTP 53 SECURE-POP3 54 SECURE-TELNET 55 SIP 56 SKINNY 57 SKYPE 58 SMTP 59 SNMP 60 SOCKS 61 SQLNET 62 SQLSERVER 63 SSH 64 STREAMWORK 65 NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack 1.0 iv Contents SUNRPC 66 SYSLOG 67 TELNET 68 TFTP 69 VDOLIVE 70 WINMX 71 NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack 1.0 v Contents NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack 1.0 vi CHAPTER 1 Release Notes for NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack 1.0 NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack Overview The Network Based Application Recognition (NBAR2) Standard Protocol Pack 1.0 is provided as the base protocol pack with an unlicensed Cisco image on a device. -

Secure Border Gateway Protocol (S-BGP) — Real World Performance and Deployment Issues

Secure Border Gateway Protocol (S-BGP) — Real World Performance and Deployment Issues Stephen Kent, Charles Lynn, Joanne Mikkelson, and Karen Seo BBN Technologies Abstract configuration information, or routing databases may be The Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), which is used to modified or replaced illicitly via unauthorized access to distribute routing information between autonomous a router, or to a server from which router software is systems, is an important component of the Internet's downloaded, or via a spoofed distribution channel, etc. routing infrastructure. Secure BGP (S-BGP) addresses Such attacks could result in transmission of fictitious critical BGP vulnerabilities by providing a scalable BGP messages, modification or replay of valid means of verifying the authenticity and authorization of messages, or suppression of valid messages. If BGP control traffic. To facilitate widespread adoption, cryptographic keying material is used to secure BGP S-BGP must avoid introducing undue overhead control traffic, that too may be compromised. We have (processing, bandwidth, storage) and must be developed security enhancements to BGP that address incrementally deployable, i.e., interoperable with BGP. most of these vulnerabilities by providing a secure, To provide a proof of concept demonstration, we scalable system: Secure-BGP (S-BGP) [1,3]. Better developed a prototype implementation of S-BGP and physical, procedural and basic communication security deployed it in DARPA’s CAIRN testbed. Real Internet for BGP routers could address some of these attacks. BGP traffic was fed to the testbed routers via replay of a However, such measures would not counter any of the recorded BGP peering session with an ISP’s BGP many forms of attacks that compromise routers router. -

Network Working Group Internet Architecture Board Request for Comments: 1720 J

Network Working Group Internet Architecture Board Request for Comments: 1720 J. Postel, Editor Obsoletes: RFCs 1610, 1600, 1540, 1500, November 1994 1410, 1360, 1280, 1250, 1100, 1083, 1130, 1140, 1200 STD: 1 Category: Standards Track INTERNET OFFICIAL PROTOCOL STANDARDS Status of this Memo This memo describes the state of standardization of protocols used in the Internet as determined by the Internet Architecture Board (IAB). This memo is an Internet Standard. Distribution of this memo is unlimited. Table of Contents Introduction . 2 1. The Standardization Process . 3 2. The Request for Comments Documents . 5 3. Other Reference Documents . 6 3.1. Assigned Numbers . 6 3.2. Gateway Requirements . 6 3.3. Host Requirements . 6 3.4. The MIL-STD Documents . 6 4. Explanation of Terms . 7 4.1. Definitions of Protocol State (Maturity Level) . 8 4.1.1. Standard Protocol . 8 4.1.2. Draft Standard Protocol . 9 4.1.3. Proposed Standard Protocol . 9 4.1.4. Experimental Protocol . 9 4.1.5. Informational Protocol . 9 4.1.6. Historic Protocol . 9 4.2. Definitions of Protocol Status (Requirement Level) . 9 4.2.1. Required Protocol . 10 4.2.2. Recommended Protocol . 10 4.2.3. Elective Protocol . 10 4.2.4. Limited Use Protocol . 10 4.2.5. Not Recommended Protocol . 10 5. The Standards Track . 10 5.1. The RFC Processing Decision Table . 10 5.2. The Standards Track Diagram . 12 6. The Protocols . 14 6.1. Recent Changes . 14 Internet Architecture Board [Page 1] RFC 1720 Internet Standards November 1994 6.1.1. New RFCs . 14 6.1.2. -

Protecting the Integrity of Internet Routing: Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) Route Origin Validation

NIST SPECIAL PUBLICATION 1800-14C Protecting the Integrity of Internet Routing: Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) Route Origin Validation Volume C: How-To Guides William Haag Applied Cybersecurity Division Information Technology Laboratory Doug Montgomery Advanced Network Technologies Division Information Technology Laboratory Allen Tan The MITRE Corporation McLean, VA William C. Barker Dakota Consulting Silver Spring, MD June 2019 This publication is available free of charge from: https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1800-14 The first draft of this publication is available free of charge from: https://www.nccoe.nist.gov/sites/default/files/library/sp1800/sidr-piir-nist-sp1800-14-draft.pdf This publication DISCLAIMER is available Certain commercial entities, equipment, products, or materials may be identified by name or company logo or other insignia in order to acknowledge their participation in this collaboration or to describe an free experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply special of status or relationship with NIST or recommendation or endorsement by NIST or NCCoE; neither is it charge intended to imply that the entities, equipment, products, or materials are necessarily the best available for the purpose. from: http://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1800-14. National Institute of Standards and Technology Special Publication 1800-14C, Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. Spec. Publ. 1800-14C, 61 pages, (June 2019), CODEN: NSPUE2 FEEDBACK As a private-public partnership, we are always seeking feedback on our Practice Guides. We are particularly interested in seeing how businesses apply NCCoE reference designs in the real world. If you have implemented the reference design, or have questions about applying it in your environment, please email us at [email protected]. -

Appendix a Protocol Filters

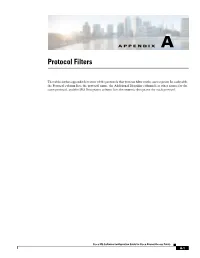

APPENDIX A Protocol Filters The tables in this appendix list some of the protocols that you can filter on the access point. In each table, the Protocol column lists the protocol name, the Additional Identifier column lists other names for the same protocol, and the ISO Designator column lists the numeric designator for each protocol. Cisco IOS Software Configuration Guide for Cisco Aironet Access Points A-1 Appendix A Protocol Filters Table A-1 EtherType Protocols Protocol Additional Identifier ISO Designator ARP — 0x0806 RARP — 0x8035 IP — 0x0800 Berkeley Trailer Negotiation — 0x1000 LAN Test — 0x0708 X.25 Level3 X.25 0x0805 Banyan — 0x0BAD CDP — 0x2000 DEC XNS XNS 0x6000 DEC MOP Dump/Load — 0x6001 DEC MOP MOP 0x6002 DEC LAT LAT 0x6004 Ethertalk — 0x809B Appletalk ARP Appletalk 0x80F3 AARP IPX 802.2 — 0x00E0 IPX 802.3 — 0x00FF Novell IPX (old) — 0x8137 Novell IPX (new) IPX 0x8138 EAPOL (old) — 0x8180 EAPOL (new) — 0x888E Telxon TXP TXP 0x8729 Aironet DDP DDP 0x872D Enet Config Test — 0x9000 NetBUI — 0xF0F0 Cisco IOS Software Configuration Guide for Cisco Aironet Access Points A-2 Appendix A Protocol Filters Table A-2 IP Protocols Protocol Additional Identifier ISO Designator dummy — 0 Internet Control Message Protocol ICMP 1 Internet Group Management Protocol IGMP 2 Transmission Control Protocol TCP 6 Exterior Gateway Protocol EGP 8 PUP — 12 CHAOS — 16 User Datagram Protocol UDP 17 XNS-IDP IDP 22 ISO-TP4 TP4 29 ISO-CNLP CNLP 80 Banyan VINES VINES 83 Encapsulation Header encap_hdr 98 Spectralink Voice Protocol SVP 119 Spectralink raw -

Introduction to the Border Gateway Protocol – Case Study Using GNS3

Introduction to The Border Gateway Protocol – Case Study using GNS3 Sreenivasan Narasimhan1, Haniph Latchman2 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Florida, Gainesville, USA [email protected], [email protected] Abstract – As the internet evolves to become a vital resource for many organizations, configuring The Border Gateway protocol (BGP) as an exterior gateway protocol in order to connect to the Internet Service Providers (ISP) is crucial. The BGP system exchanges network reachability information with other BGP peers from which Autonomous System-level policy decisions can be made. Hence, BGP can also be described as Inter-Domain Routing (Inter-Autonomous System) Protocol. It guarantees loop-free exchange of information between BGP peers. Enterprises need to connect to two or more ISPs in order to provide redundancy as well as to improve efficiency. This is called Multihoming and is an important feature provided by BGP. In this way, organizations do not have to be constrained by the routing policy decisions of a particular ISP. BGP, unlike many of the other routing protocols is not used to learn about routes but to provide greater flow control between competitive Autonomous Systems. In this paper, we present a study on BGP, use a network simulator to configure BGP and implement its route-manipulation techniques. Index Terms – Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), Internet Service Provider (ISP), Autonomous System, Multihoming, GNS3. 1. INTRODUCTION Figure 1. Internet using BGP [2]. Routing protocols are broadly classified into two types – Link State In the figure, AS 65500 learns about the route 172.18.0.0/16 through routing (LSR) protocol and Distance Vector (DV) routing protocol. -

VSI TCP/IP Services for Openvms Concepts and Planning

VSI OpenVMS VSI TCP/IP Services for OpenVMS Concepts and Planning Document Number: DO-TCPCPL-01A Publication Date: October 2020 Revision Update Information: This is a new manual. Operating System and Version: VSI OpenVMS Integrity Version 8.4-2 VSI OpenVMS Alpha Version 8.4-2L1 Software Version: VSI TCP/IP Services Version 5.7 VMS Software, Inc. (VSI) Burlington, Massachusetts, USA VSI TCP/IP Services for OpenVMS Concepts and Planning Copyright © 2020 VMS Software, Inc. (VSI), Burlington, Massachusetts, USA Legal Notice Confidential computer software. Valid license from VSI required for possession, use or copying. Consistent with FAR 12.211 and 12.212, Commercial Computer Software, Computer Software Documentation, and Technical Data for Commercial Items are licensed to the U.S. Government under vendor's standard commercial license. The information contained herein is subject to change without notice. The only warranties for VSI products and services are set forth in the express warranty statements accompanying such products and services. Nothing herein should be construed as constituting an additional warranty. VSI shall not be liable for technical or editorial errors or omissions contained herein. HPE, HPE Integrity, HPE Alpha, and HPE Proliant are trademarks or registered trademarks of Hewlett Packard Enterprise. Intel, Itanium and IA-64 are trademarks or registered trademarks of Intel Corporation or its subsidiaries in the United States and other countries. UNIX is a registered trademark of The Open Group. The VSI OpenVMS documentation set is available on DVD. ii VSI TCP/IP Services for OpenVMS Concepts and Planning Preface ................................................................................................................................... vii 1. About VSI .................................................................................................................... vii 2. Intended Audience ....................................................................................................... -

Securing the Border Gateway Protocol by Stephen T

September 2003 Volume 6, Number 3 A Quarterly Technical Publication for From The Editor Internet and Intranet Professionals In This Issue The task of adding security to Internet protocols and applications is a large and complex one. From a user’s point of view, the security- enhanced version of any given component should behave just like the From the Editor .......................1 old version, just be “better and more secure.” In some cases this is simple. Many of us now use a Secure Shell Protocol (SSH) client in place of Telnet, and shop online using the secure version of HTTP. But Securing BGP: S-BGP...............2 there is still work to be done to ensure that all of our protocols and associated applications provide security. In this issue we will look at Securing BGP: soBGP ............15 routing, specifically the Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) and efforts that are underway to provide security for this critical component of the Internet infrastructure. As is often the case with emerging Internet Virus Trends ..........................23 technologies, there exists more than one proposed solution for securing BGP. Two solutions, S-BGP and soBGP, are described by Steve Kent and Russ White, respectively. IPv6 Behind the Wall .............34 The Internet gets attacked by various forms of viruses and worms with Call for Papers .......................40 some regularity. Some of these attacks have been quite sophisticated and have caused a great deal of nuisance in recent months. The effects following the Sobig.F virus are still very much being felt as I write this. Fragments ..............................41 Tom Chen gives us an overview of the trends surrounding viruses and worms. -

Bgp Name/CLI Keyword Border Gateway Protocol Full Name Border

BGP Name/CLI Keyword bgp Full Name Border Gateway Protocol Description Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) is a protocol designed to share network information (for example network reachability) between autonomous systems (AS). According to the information, the BGP routers build/modify their routing tables. The protocol was designed to replace the Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP). Usually the protocol uses TCP/UDP ports 179 as default. Reference http://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc4274 Global ID L4:179 ID 11 Known Mappings UDP Port 179 TCP Port 179 IP Protocol - IP Version IPv4 Support Yes IPv6 Support Yes Application Group - Category - Sub Category - NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack 1.0 1 BGP P2P Technology No Encrypted No Tunnel No Underlying Protocols - • BITTORRENT, page 4 • CITRIX, page 5 • DHCP, page 6 • DIRECTCONNECT, page 7 • DNS, page 8 • EDONKEY, page 9 • EGP, page 10 • EIGRP, page 11 • EXCHANGE, page 12 • FASTTRACK, page 13 • FINGER, page 14 • FTP, page 15 • GNUTELLA, page 16 • GOPHER, page 17 • GRE, page 18 • H323, page 19 • HTTP, page 20 • ICMP, page 21 • IMAP, page 22 • IPINIP, page 23 • IPV6-ICMP, page 24 • IRC, page 25 • KAZAA2, page 26 • KERBEROS, page 27 • L2TP, page 28 • LDAP, page 29 • MGCP, page 30 NBAR2 Standard Protocol Pack 1.0 2 BGP • NETBIOS, page 31 • NETSHOW, page 32 • NFS, page 33 • NNTP, page 34 • NOTES, page 35 • NTP, page 36 • OSPF, page 37 • POP3, page 38 • PPTP, page 39 • PRINTER, page 40 • RIP, page 41 • RTCP, page 42 • RTP, page 43 • RTSP, page 44 • SAP, page 45 • SECURE-FTP, page 46 • SECURE-HTTP, page 47 • SECURE-IMAP, -

Bigp- a New Single Protocol That Can Work As an Igp (Interior Gateway Protocol) As Well As Egp (Exterior Gateway Protocol)

Manuscript Number: IJV2435 BIGP- A NEW SINGLE PROTOCOL THAT CAN WORK AS AN IGP (INTERIOR GATEWAY PROTOCOL) AS WELL AS EGP (EXTERIOR GATEWAY PROTOCOL) Isha Gupta ASET/CSE Department, Noida, India [email protected] the now obsolete Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP), as Abstract- EGP and IGP are the key components the standard exterior gateway-routing protocol used in the of the present internet infrastructure. Routers in global Internet. BGP solves serious problems with EGP a domain forward IP packet within and between and scales to Internet growth more efficiently [1,11]. domains. Each domain uses an intra-domain routing protocol known as Interior Gateway Protocol (IGP) like IS-IS, OSPF, RIP etc to populate the routing tables of its routers. Routing information must also be exchanged between domains to ensure that a host in one domain can reach another host in remote domain. This role is performed by inter-domain routing protocol called Exterior Gateway Protocol (EGP). Basically EGP used these days is Border Gateway Protocol (BGP). Basic difference between the both is that BGP has smaller convergence as compared to the IGP’s. And IGP’s on the other hand have lesser scalability as compared to the BGP. So in this paper a proposal to create a new protocol is given which can act as an IGP when we consider inter-domain transfer of traffic and acts as BGP when we consider intra-domain transfer of traffic. Figures 1: BGP topology In the above figure a simple BGP topology is shown. It consists of three autonomous systems which are linked together using serial cables. -

Secure Border Gateway Protocol (Secure-BGP) Stephen Kent, Charles Lynn, and Karen Seo

Secure Border Gateway Protocol (Secure-BGP) Stephen Kent, Charles Lynn, and Karen Seo Published in IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications Vol. 18, No. 4, April 2000, pp. 582-592 Copyright 2000 IEEE. Personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or to reuse any copyrighted component of this work in other works must be obtained from the IEEE. This material is presented to ensure timely dissemination of scholarly and technical work. Copyright and all rights therein are retained by authors or by other copyright holders. All persons copying this information are expected to adhere to the terms and constraints invoked by each author’s copyright. In most cases, these works may not be reposted without the explicit permission of the copyright holder. Abstract-- The Border Gateway Protocol (BGP), which is used to distribute routing information between autonomous systems (ASes), is a critical component of the Internet’s routing infrastructure. It is highly vulnerable to a variety of malicious attacks, due to the lack of a secure means of verifying the authenticity and legitimacy of BGP control traffic. This document describes a secure, scalable, deployable architecture (S-BGP) for an authorization and authentication system that addresses most of the security problems associated with BGP. The paper discusses the vulnerabilities and security requirements associated with BGP, describes the S-BGP countermeasures, and explains how they address these vulnerabilities and requirements. In addition, this paper provides a comparison of this architecture with other approaches that have been proposed, analyzes the performance implications of the proposed countermeasures, and addresses operational issues.