Is the Motherist Approach More Helpful in Obtaining Women's Rights Than a Feminist Approach? a Comparative Study of Lebanon and Liberia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia

‘Listen, Politics is not for Children:’ Adult Authority, Social Conflict, and Youth Survival Strategies in Post Civil War Liberia. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Henryatta Louise Ballah Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2012 Dissertation Committee: Drs. Ousman Kobo, Advisor Antoinette Errante Ahmad Sikianga i Copyright by Henryatta Louise Ballah 2012 ii Abstract This dissertation explores the historical causes of the Liberian civil war (1989- 2003), with a keen attention to the history of Liberian youth, since the beginning of the Republic in 1847. I carefully analyzed youth engagements in social and political change throughout the country’s history, including the ways by which the civil war impacted the youth and inspired them to create new social and economic spaces for themselves. As will be demonstrated in various chapters, despite their marginalization by the state, the youth have played a crucial role in the quest for democratization in the country, especially since the 1960s. I place my analysis of the youth in deep societal structures related to Liberia’s colonial past and neo-colonial status, as well as the impact of external factors, such as the financial and military support the regime of Samuel Doe received from the United States during the cold war and the influence of other African nations. I emphasize that the socio-economic and political policies implemented by the Americo- Liberians (freed slaves from the U.S.) who settled in the country beginning in 1822, helped lay the foundation for the civil war. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

Maternal Feminism Discussion

H-Women Maternal Feminism Discussion Page published by Kolt Ewing on Thursday, June 12, 2014 Maternal Feminism Discussion July, August 1996 Original Query for Info from Heather L. [email protected] 15 July 1996 I am revising a paper for publication and have been asked to include a more critical discussion of maternal feminism that reflects the kinds of questions feminist historians have posed regarding this idea. In this paper I am looking at the Needlework Guild of Canada. This is a voluntary organization that originated in England and then emerged in Canada in 1892. The women in this group collected clothing and goods to meet the needs of state-operated orphanages, hospitals, homes, and charities. Does anyone know of any work, preferably Canadian, with a contemporary discussion of maternal feminism which goes beyond the class critique and/or identifies the debates surrounding the use of this concept? I would appreciate any sources you could suggest, as I am unfamiliar with this literature. [Editor Note: For bibliography on Maternal Feminism, see bibliography section on H-Women home page at http://h-net2.msu.edu/~women/bibs Responses: >From Eileen Boris [email protected] 17 July 1996 ...The question remains, though, is maternal feminism the proper term? Is maternalism feminism? Is mother-talk strategy, discourse, or political position? >From Karen Offen [email protected] 17 July 1996 ...But first, it would be good to know more about the work of your Needlework Guild and the organization's perspective. Was there a "feminist" component of any kind, i.e. -

Women in Islamic Societies: a Selected Review of Social Scientific Literature

WOMEN IN ISLAMIC SOCIETIES: A SELECTED REVIEW OF SOCIAL SCIENTIFIC LITERATURE A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the Office of the Director of National Intelligence/National Intelligence Council (ODNI/ADDNIA/NIC) and Central Intelligence Agency/Directorate of Science & Technology November 2005 Author: Priscilla Offenhauer Project Manager: Alice Buchalter Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 205404840 Tel: 2027073900 Fax:202 707 3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd 57 Years of Service to the Federal Government 1948 – 2005 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Women in Islamic Societies PREFACE Half a billion Muslim women inhabit some 45 Muslim-majority countries, and another 30 or more countries have significant Muslim minorities, including, increasingly, countries in the developed West. This study provides a literature review of recent empirical social science scholarship that addresses the actualities of women’s lives in Muslim societies across multiple geographic regions. The study seeks simultaneously to orient the reader in the available social scientific literature on the major dimensions of women’s lives and to present analyses of empirical findings that emerge from these bodies of literature. Because the scholarly literature on Muslim women has grown voluminous in the past two decades, this study is necessarily selective in its coverage. It highlights major works and representative studies in each of several subject areas and alerts the reader to additional significant research in lengthy footnotes. In order to handle a literature that has grown voluminous in the past two decades, the study includes an “Introduction” and a section on “The Scholarship on Women in Islamic Societies” that offer general observationsbird’s eye viewsof the literature as a whole. -

Decentering Agency in Feminist Theory: Recuperating the Family As a Social Project☆

Women's Studies International Forum 35 (2012) 153–165 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Women's Studies International Forum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif Decentering agency in feminist theory: Recuperating the family as a social project☆ Amy Borovoy a, Kristen Ghodsee b,⁎ a East Asian Studies Department, Princeton University, 211 Jones Hall, Princeton, NJ 08544–1008, USA b Gender and Women's Studies, Bowdoin College, 7100 College Station, Brunswick, ME 04011, USA article info Synopsis Available online 21 April 2012 Ethnographic investigations demonstrate that there are many cultures in which women relin- quish rights for broader social goods and protections, which are equally acceptable, if not more desirable, to women. These include Western European social democracies, Eastern European post socialist nations, and the East Asian industrialized nations. Exploring these gender politics provides a powerful window into how the liberal emphasis on “choice” captures only one nar- row aspect of what is at stake for women in issues such as feminist debates about domesticity and the politics of abortion and family planning. In this article we draw on Japan and Bulgaria as our case studies, and we historicize the brand of social feminism that we are discussing, locating it in the mission to incorporate women into national agendas during the interwar pe- riod in many locations throughout the industrialized world as well as in the diverse mandates of early socialist feminism in the United States. We argue that “social feminism” can help sharpen the critiques of liberal feminism mobilized by anthropologists under the banner of “cultural relativism.” © 2012 Elsevier Ltd. -

Q:\Research Files\Research Papers\Carrol03(Format).Wpd

Are U.S. Women State Legislators Accountable to Women? The Complementary Roles of Feminist Identity and Women’s Organizations Susan J. Carroll Rutgers University Paper prepared for presentation at the Gender and Social Capital Conference, St. John’s College, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, May 2-3, 2003 Numerous scholars have argued that the increased numerical representation of women among legislators is likely to lead to increased substantive representation of women, and a number of studies have presented evidence suggesting a strong relationship between the presence of women legislators and attention to women’s issues within legislative bodies (e.g., Dodson and Carroll 1991; Thomas 1994; Carroll 1994; Carroll 2001; Saint-Germain 1989). While we have considerable evidence that women legislators give greater priority to women’s issues than their male colleagues, we know less about why they do so. What is the process underlying the substantive representation of women by women legislators? Why does the representation of women by women legislators happen? This paper examines these questions with particular attention to the role of women’s organizations and networks. Anne Phillips has argued that the most troubling question surrounding the political representation of women is the question of accountability (1995, 56). Observing that “Representation depends on the continuing relationship between representatives and the represented ” (1995, 82), Phillips concludes “there is no obvious way of establishing strict accountability to women as a group” (1995, 83). Thus, for Phillips, “Changing the gender composition of elected assemblies is largely an enabling condition... but it cannot present itself as a guarantee [of greater substantive representation for women]” (1995, 83). -

The London School of Economics and Political Science The

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Theses Online The London School of Economics and Political Science The Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement: Activism Across Borders for Palestinian Justice Suzanne Morrison A thesis submitted to the Department of Government of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2015 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 75,359 words. 2 Abstract On 7 July 2005, a global call for Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) was declared to people around the world to enact boycott initiatives and pressure their respective governments to sanction Israel until it complies with international law and respects universal principles of human rights. The call was endorsed by over 170 Palestinian associations, trade unions, non-governmental organizations, charities, and other Palestinian groups. The call mentioned how broad BDS campaigns were utilized in the South African struggle against apartheid, and how these efforts served as an inspiration to those seeking justice for Palestinians. -

The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements

The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements By Laura K. Nelson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kim Voss, Chair Professor Raka Ray Professor Robin Einhorn Fall 2014 Copyright 2014 by Laura K. Nelson 1 Abstract The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements by Laura K. Nelson Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Kim Voss, Chair This dissertation challenges the widely accepted historical accounts of women's movements in the United States. Second-wave feminism, claim historians, was unique because of its development of radical feminism, defined by its insistence on changing consciousness, its focus on women being oppressed as a sex-class, and its efforts to emphasize the political nature of personal problems. I show that these features of second-wave radical feminism were not in fact unique but existed in almost identical forms during the first wave. Moreover, within each wave of feminism there were debates about the best way to fight women's oppression. As radical feminists were arguing that men as a sex-class oppress women as a sex-class, other feminists were claiming that the social system, not men, is to blame. This debate existed in both the first and second waves. Importantly, in both the first and the second wave there was a geographical dimension to these debates: women and organizations in Chicago argued that the social system was to blame while women and organizations in New York City argued that men were to blame. -

In Search of Equality for Women: from Suffrage to Civil Rights

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 2021 In Search of Equality for Women: From Suffrage to Civil Rights Nan D. Hunter Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/2390 https://ssrn.com/abstract=3873451 Duquesne Law Review, Vol. 59, 125-166. This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Law and Gender Commons, Law and Race Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons In Search of Equality for Women: From Suffrage to Civil Rights Nan D. Hunter* ABSTRACT This article analyzes women’s rights advocacy and its impact on evolutions in the meaning of gender equality during the period from the achievement of suffrage in 1920 until the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The primary lesson is that one cannot separate the conceptualiza- tion of equality or the jurisprudential philosophy underlying it from the dynamics and characteristics of the social movements that ac- tively give it life. Social movements identify the institutions and practices that will be challenged, which in turn determines which doctrinal issues will provide the raw material for jurisgenerative change. Without understanding a movement’s strategy and oppor- tunities for action, one cannot know why law developed as it did. This article also demonstrates that this phase of women’s rights advocacy comprised not one movement—as it is usually described— but three: the suffragists who turned to a campaign for an Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) after winning the Nineteenth Amend- ment; the organizations inside and outside the labor movement that prioritized the wellbeing of women workers in the industrial econ- omy; and the birth control movement. -

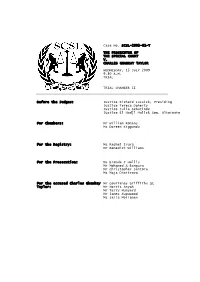

Case No. SCSL-2003-01-T the PROSECUTOR of the SPECIAL

Case No. SCSL-2003-01-T THE PROSECUTOR OF THE SPECIAL COURT V. CHARLES GHANKAY TAYLOR WEDNESDAY, 15 JULY 2009 9.30 A.M. TRIAL TRIAL CHAMBER II Before the Judges: Justice Richard Lussick, Presiding Justice Teresa Doherty Justice Julia Sebutinde Justice El Hadji Malick Sow, Alternate For Chambers: Mr William Romans Ms Doreen Kiggundu For the Registry: Ms Rachel Irura Mr Benedict Williams For the Prosecution: Ms Brenda J Hollis Mr Mohamed A Bangura Mr Christopher Santora Ms Maja Dimitrova For the accused Charles Ghankay Mr Courtenay Griffiths QC Taylor: Mr Morris Anyah Mr Terry Munyard Mr James Supuwood Ms Salla Moilanen CHARLES TAYLOR Page 24457 15 JULY 2009 OPEN SESSION 1 Wednesday, 15 July 2009 2 [Open session] 3 [The accused present] 4 [Upon commencing at 9.30 a.m.] 09:31:08 5 PRESIDING JUDGE: Good morning. We will take appearances 6 first, please. 7 MS HOLLIS: Good morning Mr President, your Honours, 8 opposing counsel. This morning for the Prosecution, Mohamed A 9 Bangura, Christopher Santora, Maja Dimitrova and myself Brenda J 09:31:38 10 Hollis. And, Mr President, just to bring to your attention, 11 there are two quick matters the Prosecution would ask to address 12 before the accused recommences his testimony. 13 PRESIDING JUDGE: Yes, thank you, Ms Hollis. For the 14 Defence, Mr Griffiths? 09:32:00 15 MR GRIFFITHS: Good morning. For the Defence today, myself 16 Courtenay Griffiths, assisted by my learned friends Mr Morris 17 Anyah, Mr Terry Munyard and Cllr Supuwood. Also with us is Salla 18 Moilanen, our case manager. -

Civil Marriage in Lebanon

Empowering Women or Dislodging Sectarianism?: Civil Marriage in Lebanon Sherifa Zuhurt In this article, I reflect on the proposed Lebanese civil marriage law, which initiated a political crisis in Lebanon in March of 1998 and was followed by an indefinite shelving of that proposed law. Many Westerners assume that women in today's Middle East passively submit to extreme male chauvinism and glaring legal inequalities. In fact, Middle Eastern women have been actively engaged in a quest for empowerment and equity through legal, educational, political, and workplace reforms for many decades, and through publication of their writings in some countries for over a century. Although women's rights were at stake in the proposed law, it is curious that many failed to perceive the connection between legal reform and women's empowerment. Those who understand this linkage only too well are the most frequent opponents of such legal reform, arguing that it will destroy the very fabric of society and its existing religious and social divisions. First, I will provide some information on the history of sectarianism (known as ta'ifzyya in Arabic) in Lebanon. The drama surrounding the proposed bill's debut will be followed by information on women's politically and socially transitional status in the country. I relate women's status to their inability to lobby effectively for such a reform. I will allude to similar or related regional reforms in the area of personal status in order to challenge the idea of Lebanon's exceptionalism. I then explore the politicized nature of the t Sherifa Zuhur holds a Ph.D. -

Farming Palestine for Freedom

Samer Abdelnour, Alaa Tartir and Rami Zurayk Farming Palestine for freedom Discussion paper [or working paper, etc.] Original citation: Abdelnour, Samer, Tartir, Alaa and Zurayk, Rami (2012) Farming Palestine for freedom. Policy brief, Al-Shabaka, Washington D.C. This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/50329/ Originally available from Al-Shabaka Available in LSE Research Online: May 2013 © 2012 The Author LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. [email protected] www.al-shabaka.org al-shabaka policy brief FARMING PALESTINE FOR FREEDOM By Samer Abdelnour, Alaa Tartir, and Rami Zurayk July 2012 Overview For Palestinians, agriculture is more than a source of income or an economic category in budgets and plans. It is tied to the people’s history, identity, and self-expression, and drives the struggle against Israel’s Separation Wall. In this brief, Lebanese activist, author, and agronomist Rami Zurayk joins Al-Shabaka Policy Advisors Samer Abdelnour and Alaa Tartir to tackle the almost spiritual significance of the land to the Palestinians and the deliberate Israeli efforts to break the link between farmers and their crops.