{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAD Visionaries!

Press Release MUSEUM OF ARTS AND DESIGN TO PRESENT ANNUAL VISIONARIES! AWARDS NOVEMBER 20, 2013 The Evening Will Honor Materialise CEO and Founder Wilfried Vancraen, Artist Frank Stella, Vilcek Foundation Executive Director Rick Kinsel, and Designers David and Sybil Yurman NEW YORK, NY (November 5, 2013) – On Wednesday, November 20, PRESS CONTACT 2013, the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) will host its 2013 Visionaries! Claire Laporte/Carnelia Garcia Gala, celebrating five influential creators and leaders in the art, craft, and Museum of Arts and Design design industries, whose work personifies the Museum’s mission to explore 212.299.7737 and celebrate contemporary creativity across all media: [email protected] • Wilfried Vancraen, Chief Executive Officer and Founder of Materialise, an international additive manufacturing company started in Belgium. MAD PRESS RESOURCES For more than twenty years, Materialise has been working with image library designers and scientists to help expand design, manufacturing, and release as .pdf biomedical research into new frontiers, while remaining committed to artistic creativity, sustainability and the improvement of people’s lives. MAD LINKS • Frank Stella, legendary painter and printmaker, most noted for his Minimalist, Post-Painterly Abstract works has challenged ideas collections database of abstraction and of painting itself by negating the evidence of facebook brushwork and asserting the flatness of the canvas. Today, Stella youtube continues to explore new forms and aesthetic avenues in creating flickr multidimensional, hybrid sculptures that combine painting with twitter geometrical and architectural elements. • Rick Kinsel, Executive Director, The Vilcek Foundation. For more than 10 years, the Vilcek Foundation, under Kinsel's leadership, has been an important philanthropic supporter of the arts and sciences. -

The Factory of Visual

ì I PICTURE THE MOST COMPREHENSIVE LINE OF PRODUCTS AND SERVICES "bey FOR THE JEWELRY CRAFTS Carrying IN THE UNITED STATES A Torch For You AND YOU HAVE A GOOD PICTURE OF It's the "Little Torch", featuring the new controllable, méf » SINCE 1923 needle point flame. The Little Torch is a preci- sion engineered, highly versatile instrument capa- devest inc. * ble of doing seemingly impossible tasks with ease. This accurate performer welds an unlimited range of materials (from less than .001" copper to 16 gauge steel, to plastics and ceramics and glass) with incomparable precision. It solders (hard or soft) with amazing versatility, maneuvering easily in the tightest places. The Little Torch brazes even the tiniest components with unsurpassed accuracy, making it ideal for pre- cision bonding of high temp, alloys. It heats any mate- rial to extraordinary temperatures (up to 6300° F.*) and offers an unlimited array of flame settings and sizes. And the Little Torch is safe to use. It's the big answer to any small job. As specialists in the soldering field, Abbey Materials also carries a full line of the most popular hard and soft solders and fluxes. Available to the consumer at manufacturers' low prices. Like we said, Abbey's carrying a torch for you. Little Torch in HANDY KIT - —STARTER SET—$59.95 7 « '.JBv STARTER SET WITH Swest, Inc. (Formerly Southwest Smelting & Refining REGULATORS—$149.95 " | jfc, Co., Inc.) is a major supplier to the jewelry and jewelry PRECISION REGULATORS: crafts fields of tools, supplies and equipment for casting, OXYGEN — $49.50 ^J¡¡r »Br GAS — $49.50 electroplating, soldering, grinding, polishing, cleaning, Complete melting and engraving. -

2020 Impact Report

20 20 IMPACT REPORT Demond Melancon, Big Chief of the Young Seminole Hunters – 2020 COVID-19 Relief Grant Recipient, New Orleans, Louisiana, Photo courtesy of Christopher Porché West OUR MISSION A Letter from CERF+ Plan + Pivot + Partner CERF+’s mission is to serve artists who work in craft disciplines by providing a safety In the first two decades of the 21st century,CERF+ ’s safety net of services gradually net to support strong and sustainable careers. CERF+’s core services are education expanded to better meet artists’ needs in response to a series of unprecedented natural programs, resources on readiness, response and recovery, advocacy, network building, disasters. The tragic events of this past year — the pandemic, another spate of catastrophic and emergency relief assistance. natural disasters, as well as the societal emergency of racial injustice — have thrust us into a new era in which we have had to rethink our work. Paramount in this moment has been BOARD OF DIRECTORS expanding our definition of “emergency” and how we respond to artists in crises. Tanya Aguiñiga Don Friedlich Reed McMillan, Past Chair While we were able to sustain our longstanding relief services, we also faced new realities, which required different actions. Drawing from the lessons we learned from administering Jono Anzalone, Vice Chair John Haworth* Perry Price, Treasurer aid programs during and after major emergencies in the previous two decades, we knew Malene Barnett Cinda Holt, Chair Paul Sacaridiz that our efforts would entail both a sprint and a marathon, requiring us to plan, pivot, Barry Bergey Ande Maricich* Jaime Suárez and partner. -

2020 Impact Report

20 20 IMPACT REPORT Demond Melancon, Big Chief of the Young Seminole Hunters – 2020 COVID-19 Relief Grant Recipient, New Orleans, Louisiana, Photo courtesy of Christopher Porché West OUR MISSION A Letter from CERF+ Plan + Pivot + Partner CERF+’s mission is to serve artists who work in craft disciplines by providing a safety In the first two decades of the 21st century,CERF+ ’s safety net of services gradually net to support strong and sustainable careers. CERF+’s core services are education expanded to better meet artists’ needs in response to a series of unprecedented natural programs, resources on readiness, response and recovery, advocacy, network building, disasters. The tragic events of this past year — the pandemic, another spate of catastrophic and emergency relief assistance. natural disasters, as well as the societal emergency of racial injustice — have thrust us into a new era in which we have had to rethink our work. Paramount in this moment has been BOARD OF DIRECTORS expanding our definition of “emergency” and how we respond to artists in crises. Tanya Aguiñiga Don Friedlich Reed McMillan, Past Chair While we were able to sustain our longstanding relief services, we also faced new realities, which required different actions. Drawing from the lessons we learned from administering Jono Anzalone, Vice Chair John Haworth* Perry Price, Treasurer aid programs during and after major emergencies in the previous two decades, we knew Malene Barnett Cinda Holt, Chair Paul Sacaridiz that our efforts would entail both a sprint and a marathon, requiring us to plan, pivot, Barry Bergey Ande Maricich* Jaime Suárez and partner. -

An Oral History of the Furniture Society

Furniture Society Oral History B. P. Johnson 10/16/16 Building Community: An Oral History of the Furniture Society Generous support for this project was provided by Vin Ryan, Ron Abramson, and Toni Sikes. The Furniture Society expresses its gratitude for their vision and financial contributions. Narrator: Bebe Pritam Johnson (BPJ) Interviewer: Jonathan Binzen (JB) Date: October 16, 2016 Location: Mount Desert, ME Subject: Furniture Society Oral History Duration: 01:25:45 00:00:00 JB: Here we are on October 16, 2016 in Mt. Desert, Maine, and we’re recording for the oral history project for the Furniture Society. Anything else? BPJ: No. I think that establishes who, what, where. But the why part we haven’t… JB: No, we haven’t. What is the why? BPJ: Why are we in conversation? JB: And we’re in the sun, outside, on a beautiful day. I was wondering if you could talk about how you first became aware of the Furniture Society and how that went. Maybe a little about what you were doing when you first heard about the idea. BPJ: Well I recall vividly where I was and what I was doing. I had been invited by Albert LeCoff, Woodturning Center, to give a talk in Philadelphia. I don’t remember what the occasion was exactly, but he wanted the subject of the talk to revolve around collecting. A subject I felt I had—this was now some 20 years ago, plus--little enough to offer. So I knew that I would have to do research. I would have to invest some time in coming up with a 40-minute talk on a subject that he gave me more credit for having knowledge of than I actually deserved. -

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Smithsonian American Art Museum Chronological List of Past Exhibitions and Installations on View at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and its Renwick Gallery 1958-2016 ■ = EXHIBITION CATALOGUE OR CHECKLIST PUBLISHED R = RENWICK GALLERY INSTALLATION/EXHIBITION May 1921 xx1 American Portraits (WWI) ■ 2/23/58 - 3/16/58 x1 Paul Manship 7/24/64 - 8/13/64 1 Fourth All-Army Art Exhibition 7/25/64 - 8/13/64 2 Potomac Appalachian Trail Club 8/22/64 - 9/10/64 3 Sixth Biennial Creative Crafts Exhibition 9/20/64 - 10/8/64 4 Ancient Rock Paintings and Exhibitions 9/20/64 - 10/8/64 5 Capital Area Art Exhibition - Landscape Club 10/17/64 - 11/5/64 6 71st Annual Exhibition Society of Washington Artists 10/17/64 - 11/5/64 7 Wildlife Paintings of Basil Ede 11/14/64 - 12/3/64 8 Watercolors by “Pop” Hart 11/14/64 - 12/13/64 9 One Hundred Books from Finland 12/5/64 - 1/5/65 10 Vases from the Etruscan Cemetery at Cerveteri 12/13/64 - 1/3/65 11 27th Annual, American Art League 1/9/64 - 1/28/65 12 Operation Palette II - The Navy Today 2/9/65 - 2/22/65 13 Swedish Folk Art 2/28/65 - 3/21/65 14 The Dead Sea Scrolls of Japan 3/8/65 - 4/5/65 15 Danish Abstract Art 4/28/65 - 5/16/65 16 Medieval Frescoes from Yugoslavia ■ 5/28/65 - 7/5/65 17 Stuart Davis Memorial Exhibition 6/5/65 - 7/5/65 18 “Draw, Cut, Scratch, Etch -- Print!” 6/5/65 - 6/27/65 19 Mother and Child in Modern Art ■ 7/19/65 - 9/19/65 20 George Catlin’s Indian Gallery 7/24/65 - 8/15/65 21 Treasures from the Plantin-Moretus Museum Page 1 of 28 9/4/65 - 9/25/65 22 American Prints of the Sixties 9/11/65 - 1/17/65 23 The Preservation of Abu Simbel 10/14/65 - 11/14/65 24 Romanian (?) Tapestries ■ 12/2/65 - 1/9/66 25 Roots of Abstract Art in America 1910 - 1930 ■ 1/27/66 - 3/6/66 26 U.S. -

Oral History Interview with Jere Osgood, 2001 September 19-October 8

Oral history interview with Jere Osgood, 2001 September 19-October 8 Funding for this interview was provided by the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Jere Osgood on September 19 and October 8, 2001. The interview took place in Wilton, New Hampshire, and was conducted by Donna Gold for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview is part of the Nanette L. Laitman Documentation Project for Craft and Decorative Arts in America. Jere Osgood and Donna Gold have reviewed the transcript and have made corrections and emendations. The reader should bear in mind that he or she is reading a verbatim transcript of spoken, rather than written prose. Interview MS. DONNA GOLD: This is Donna Gold interviewing Jere Osgood at his home in Wilton, New Hampshire, on September 19, 2001, tape one, side one. So just tell me, you were born in Staten Island. MR. JERE OSGOOD: Staten Island, New York. MS. GOLD: And the date? MR. OSGOOD: February 7, 1936. MS. GOLD: And you were raised in Staten Island, right. MR. OSGOOD: Yeah. MS. GOLD: I was wondering whether you felt that you had the -- well, did you go into Manhattan frequently? MR. -

List of 659 Books Owned by Our Department Library, As of January 2005, Listed by Subject Category

Palomar College Cabinet & Furniture Technology This is a list of 659 books owned by our Department Library, as of January 2005, listed by subject category. Our library is a reference library not a lending library. Books or Magazines must NOT be removed from the library. Our library is located between T16 and T17 classrooms, not in the campus library. Our library is open to enrolled students during all class hours. Books are located on the shelves in broad general categories, from top left to bottom right. You must return books to the correct place on the shelf after use. Books are not located under the Dewey Decimal System. The Location column in this table indicates whether the book is located on the library shelves: (S) or in reserve: (R), or Lost (N). Book Title Book Author Location Architecture Handcrafted Doors & Windows Amy Zaffarano Rowland S Japanese Detail Architecture Sadao Hibi S English Historic Carpentry Cecil A. Hewett S Vacation Homes Home Planners, Inc. S Two Story Homes Home Planners, Inc. S A Guide to the Work of Greene and Greene Randell L. Makinson S The George White & Anna Gunn Marston House S Super Luxurious Custom Homes Mike Tecton S One Story Homes Under 2000 Sq. Ft. Home Planners, Inc. S One Story Homes Over 2000 Sq. Ft. Home Planners, Inc. S One & One Half Story Homes Home Planners, Inc. S Make Your Own Handcrafted Doors & Windows John Birchard S French Interiors and Furniture Period of Louis XIV Francis J. Geck S French Interiors and Furniture Period of Louis XIII Francis J. -

Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled By: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C

OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Ontario Crafts Council Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir and Amy C. Wallace Compiled in: June to August 2010 Last Updated: 17-Aug-10 Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 In Celebration of pp. 1-10 Official opening, OCC headquarters, This article is a series of photographs and the Ontario Crafts Crossroads, Joan Chalmers, Thoma Ewen, blurbs detailing the official opening of the Council Tamara Jaworska, Dora de Pedery, Judith OCC, the Crossroads exhibition, and some Almond-Best, Stan Wellington, David behind the scenes with the Council. Reid, Karl Schantz, Sandra Dunn. Craftsman 1976 April 1 1 Hi Fibres '76 p. 12 Exhibition, sculptural works, textile forms, This article details Hi Fibres '76, an OCC Gallery, Deirdre Spencer, Handcraft exhibition of sculptural works and textile House, Lynda Gammon, Madeleine forms in the gallery of the Ontario Crafts Chisholm, Charlotte Trende, Setsuko Council throughout February. Piroche, Bob Polinsky, Evelyn Roth, Charlotte Schneider, Phyllis gerhardt, Dianne Jillings, Joyce Cosgrove, Sue Proom, Margery Powel, Miriam McCarrell, Robert Held. Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 Communications pp. 1-6 First conference, structures and This article discusses the initial Weekend programs, Alan Gregson, delegates. conference of the OCC, in which the structure of the organization, the programs, and the affiliates benefits were discussed. Page 1 of 153 OCC Periodical Listing Compiled by: Caoimhe Morgan-Feir Amy C. Wallace Periodical Year Season Vo. No. Article Title Author Last Author First Pages Keywords Abstract Craftsman 1976 April 1 2 The Affiliates of pp. -

OUR GUARANTEE You Must Be Satisfied with Any Item Purchased from This Catalog Or Return It Within 60 Days for a Full Refund

Edward R. Hamilton Bookseller Company • Falls Village, Connecticut February 26, 2016 These items are in limited supply and at these prices may sell out fast. DVD 1836234 ANCIENT 7623992 GIRL, MAKE YOUR MONEY 6545157 BERNSTEIN’S PROPHETS/JESUS’ SILENT GROW! A Sister’s Guide to ORCHESTRAL MUSIC: An Owner’s YEARS. Encounters with the Protecting Your Future and Enriching Manual. By David Hurwitz. In this Unexplained takes viewers on a journey Your Life. By G. Bridgforth & G. listener’s guide, and in conjunction through the greatest religious mysteries Perry-Mason. Delivers sister-to-sister with the accompanying 17-track audio of the ages. This set includes two advice on how to master the stock CD, Hurwitz presents all of Leonard investigations: Could Ancient Prophets market, grow your income, and start Bernstein’s significant concert works See the Future? and Jesus’ Silent Years: investing in your biggest asset—you. in a detailed but approachable way. Where Was Jesus All Those Years? 88 Book Club Edition. 244 pages. 131 pages. Amadeus. Paperbound. minutes SOLDon two DVDs. TLN. OU $7.95T Broadway. Orig. Pub. at $19.95 $2.95 Pub. at $24.99SOLD OU $2.95T 2719711 THE ECSTASY OF DEFEAT: 756810X YOUR INCREDIBLE CAT: 6410421 THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF Sports Reporting at Its Finest by the Understanding the Secret Powers ANTARCTIC JOURNEYS. Ed. by Jon Editors of The Onion. From painfully of Your Pet. By David Greene. E. Lewis. Collects a heart-pounding obvious steroid revelations to superstars Interweaves scientific studies, history, assortment of 32 true, first-hand who announce trades in over-the-top TV mythology, and the claims of accounts of death-defying expeditions specials, the world of sports often seems cat-owners and concludes that cats in the earth’s southernmost wilderness. -

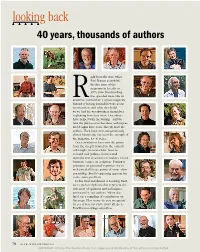

Looking Back 40 Years, Thousands of Authors

looking back 40 years, thousands of authors ight from the start, when Paul Roman assembled the first issue of the magazine in his attic in 1975, Fine Woodworking has operated more like an academic journal than a typical magazine. RInstead of having journalists write about woodworkers and what they build, we’ve had the woodworkers themselves explaining how they work. Our editors have helped with the writing—and we take the photos—but the ideas, techniques, and designs have come directly from the authors. Their hard-won and generously shared knowledge has been the strength of the magazine for 40 years. Our contributors have run the gamut from the deeply trained to the entirely self-taught, from machine mavens to hand-tool junkies, from period- reproduction absolutists to makers whose furniture verges on sculpture. Putting a premium on personal expertise, we’ve welcomed all those points of view, often presenting directly opposing approaches to the same problem. In this final installment of Looking Back, we’ve gathered photos that represent the rich array of opinions and techniques embraced by our authors. We’ve also lined up a sampling of contributors on this page. How many do you recognize? To see if you can name them all, go to FineWoodworking.com/extras. 78 FINE WOODWORKING COPYRIGHT 2016 by The Taunton Press, Inc. Copying and distribution of this article is not permitted. The best way to cut dovetails TAILS FIRST, OR PINS? BY HAND OR MACHINE? You can find dovetails right in Fine Woodworking’s logo, and there’s doubtless been some mention of Diverse takes on the dovetail. -

Wood Threads 1977, When a Man's Fancy Tumsto Fancv

Spring $2.50 Wood Threads 1977, When a man's fancy tumsto fancv. There comes a time in every Not to mention more than 170 man's life when he outgrows the bits and cutters to pick from. Or a basic power tools. When his imagi $49.99* toter kit complete with the nation calls for more. 4600 router, wrenches, edge guide, That's the perfect time for a the three bits you'll probably use the router. One of the few power tools most, and a carrying case to hold around with hardly any limitation everything. but your imagination. All in all, it's one whale of a bar Meaning you can make flutes, gain. Especially when you consider beads, reeds, rounded comers, the one feature you can't get or almost any other finishing touch anywhere else. under the sun. Plus a lot of really Rockwell engineering. practical things, like dovetails for The kind that only comes with drawers, dadoes for shelves, rabbets half a century of indus for joints, etc., etc. trial experience and on What's more, it's all pos the-job performance. for just $39.99; the pri It goes into every of a Rockwell 4600 portable and Ij2-hp Router. For some stationary tool very good reasons. aD�.. ;_ we make. Super high speed It's why (28,000 rpm), to cut fast they're all and smooth. Microm made tough, eter depth con accurate and trol to powerful. ' adjust when you're ments ready toSo let your imagi easy. Non nation go, they'll make mamng the going good.