Important Bird Areas in Namibia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16.20 TRIPOGON Roem. & Schult.^ 16.22 DINEBRA Jacq.^ 16.21

"^•^ 16.23 CYNODONTEAE • Eragrostis 201 16.20 TRIPOGON Roem. & Schult.^ Pi per or ann; csp or tufted. Clm 4-65 cm, erect, slender. keeled or rounded, ape lobed or bifid, mucronate or Lvs linear, flat, usu becoming folded and filiform; lig awned from between the lobes, lat veins smt also memb, ciliate. Infl tml, unilat linear spikes or spikelike excurrent, awns usu straight; anth 1-3. rcm, with 1 spklt per nd, exceeding the lvs; rchs visible, Tripogon is a genus of approximately 30 species, most of not concealed by the spklt. Spklt appressed, in 2 rows which are native to the tropics of the Eastern Hemisphere, along 1 side of the rchs, with 3-20 bisx fit, distal fit strl especially Africa and India. One species, Tripogon spicatus, is or stmt; dis above the glm and between the fit. Glm native to the Western Hemisphere. unequal, l(3)-veined; Im 1-3-veined, backs sHghtly 1. Tripogon spicatus (Nees) Ekman AMERICAN TRIPOGON [p. 435, 532] Tripogon spicatus grows in shallow rocky soils, usually on granite range includes the West Indies, Mexico, and South America, in outcroppings, occasionally on limestone. The flowering period, addition to central Texas. April-July (October, November), apparently depends on rainfall. Its 16.21 TRICHONEURA Andersson^ Pi ann or per. Clm 12-155 cm, nd glab, intnd sohd. Lig each other, narrow, ape acuminate and mucronate, memb; bid linear, narrow, usu flat. Infl tml, pan of 5-40 awnlike, or awned; cal well-developed, strigose; Im 3- racemosely arranged, spikelike br, exceeding the lvs; br veined, conspicuously hairy adjacent to and on the lat spreading to appressed, persistent, unilat, with 1 spklt veins, ape cleft, midveins excurrent from the sinuses, per nd. -

SEED LEAFLET No

SEED LEAFLET No. 84 September 2003 Baikiaea plurijuga Harms Taxonomy and nomenclature Botanical description Family: Fabaceae (Caesalpinioideae) A medium to large tree, 8-15 (20) m tall, with a large, Synonyms: none. dense, spreading crown. The bark is smooth and pale Vernacular/common names: Rhodesian teak, Zambe- at first, on older trees becoming fissured and cracked. zi teak, Zambezi redwood, Zimbabwean teak, Zambian Leaves are alternate and compound with 4 to 5 pairs teak (Eng.); mukusi (Botswana and Zambia); Rhode- of opposite leaflets. Each leaflet is up to 7 cm long, siese kiaat (South Africa); Zimbabwean teak, Zimbab- sparingly hairy especially on the lower surface and wean chestnut, umgusi, mukusi (Zimbabwe). midrib; the tip is rounded. The large, pink flowers are very attractive; they are borne in up to 30 cm long Distribution and habitat inflorescences. The species is confined to lowland tropical forests on the deep Kalahari sands between 13 and 20°S. It oc- curs naturally in Angola, Botswana, Namibia, Zambia and Zimbabwe, in areas with annual rainfall of 600- 1000 mm and a dry season of 6-8 months. Mature trees can withstand extreme temperatures of over 40°C and have been known to survive severe frost down to -15°C. It is mainly found in deep, infertile, sandy soils where it survives by developing a deep tap root. During the last century, most of the original Zambesi teak forests have been heavily exploited by logging, clearing of land for agriculture and frequent fires and the species is now mainly found in open, dry, deciduous woodland. The species is most typically associated with Pterocarpus angolensis, Julbernardia paniculata, Dialium englerianum. -

Freshwater Fishes

WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE state oF BIODIVERSITY 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 2 Methods 17 Chapter 3 Freshwater fishes 18 Chapter 4 Amphibians 36 Chapter 5 Reptiles 55 Chapter 6 Mammals 75 Chapter 7 Avifauna 89 Chapter 8 Flora & Vegetation 112 Chapter 9 Land and Protected Areas 139 Chapter 10 Status of River Health 159 Cover page photographs by Andrew Turner (CapeNature), Roger Bills (SAIAB) & Wicus Leeuwner. ISBN 978-0-620-39289-1 SCIENTIFIC SERVICES 2 Western Cape Province State of Biodiversity 2007 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Andrew Turner [email protected] 1 “We live at a historic moment, a time in which the world’s biological diversity is being rapidly destroyed. The present geological period has more species than any other, yet the current rate of extinction of species is greater now than at any time in the past. Ecosystems and communities are being degraded and destroyed, and species are being driven to extinction. The species that persist are losing genetic variation as the number of individuals in populations shrinks, unique populations and subspecies are destroyed, and remaining populations become increasingly isolated from one another. The cause of this loss of biological diversity at all levels is the range of human activity that alters and destroys natural habitats to suit human needs.” (Primack, 2002). CapeNature launched its State of Biodiversity Programme (SoBP) to assess and monitor the state of biodiversity in the Western Cape in 1999. This programme delivered its first report in 2002 and these reports are updated every five years. The current report (2007) reports on the changes to the state of vertebrate biodiversity and land under conservation usage. -

Investigating the Impact of Fire on the Natural Regeneration of Woody Species in Dry and Wet Miombo Woodland

Investigating the impact of fire on the natural regeneration of woody species in dry and wet Miombo woodland by Paul Mwansa Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science of Forestry and Natural Resource Science in the Faculty of AgriSciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof Ben du Toit Co-supervisor: Dr Vera De Cauwer March 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration By submitting this thesis electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. March 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za Abstract The miombo woodland is an extensive tropical seasonal woodland and dry forest formation in extent of 2.7 million km². The woodland contributes highly to maintenance and improvement of people’s livelihood security and stable growth of national economies. The woodland faces a wide range of disturbances including fire that affect vegetation structure. An investigation into the impact of fire on the natural regeneration of six tree species was conducted along a rainfall gradient. Baikiaea plurijuga, Burkea africana, Guibourtia coleosperma, Pterocarpus angolensis, Schinziophyton rautanenii and Terminalia sericea were selected on basis of being an important timber and/or utilitarian species, and the assumed abundance. The objectives of the study were to examine floristic composition, density and composition of natural regeneration; stand structure and vegetation cover within recently burnt (RB) and recently unburnt (RU) sections of the forest. -

Disaggregation of Bird Families Listed on Cms Appendix Ii

Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals 2nd Meeting of the Sessional Committee of the CMS Scientific Council (ScC-SC2) Bonn, Germany, 10 – 14 July 2017 UNEP/CMS/ScC-SC2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II (Prepared by the Appointed Councillors for Birds) Summary: The first meeting of the Sessional Committee of the Scientific Council identified the adoption of a new standard reference for avian taxonomy as an opportunity to disaggregate the higher-level taxa listed on Appendix II and to identify those that are considered to be migratory species and that have an unfavourable conservation status. The current paper presents an initial analysis of the higher-level disaggregation using the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World Volumes 1 and 2 taxonomy, and identifies the challenges in completing the analysis to identify all of the migratory species and the corresponding Range States. The document has been prepared by the COP Appointed Scientific Councilors for Birds. This is a supplementary paper to COP document UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.3 on Taxonomy and Nomenclature UNEP/CMS/ScC-Sc2/Inf.3 DISAGGREGATION OF BIRD FAMILIES LISTED ON CMS APPENDIX II 1. Through Resolution 11.19, the Conference of Parties adopted as the standard reference for bird taxonomy and nomenclature for Non-Passerine species the Handbook of the Birds of the World/BirdLife International Illustrated Checklist of the Birds of the World, Volume 1: Non-Passerines, by Josep del Hoyo and Nigel J. Collar (2014); 2. -

The Eco-Ethology of the Karoo Korhaan Eupodotis Virgorsil

THE ECO-ETHOLOGY OF THE KAROO KORHAAN EUPODOTIS VIGORSII. BY M.G.BOOBYER University of Cape Town SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE (ORNITHOLOGY) UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN RONDEBOSCH 7700 CAPE TOWN The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town University of Cape Town PREFACE The study of the Karoo Korhaan allowed me a far broader insight in to the Karoo than would otherwise have been possible. The vast openness of the Karoo is a monotony to those who have not stopped and looked. Many people were instrumental in not only encouraging me to stop and look but also in teaching me to see. The farmers on whose land I worked are to be applauded for their unquestioning approval of my activities and general enthusiasm for studies concerning the veld and I am particularly grateful to Mnr. and Mev. Obermayer (Hebron/Merino), Mnr. and Mev. Steenkamp (Inverdoorn), Mnr. Bothma (Excelsior) and Mnr. Van der Merwe. Alwyn and Joan Pienaar of Bokvlei have my deepest gratitude for their generous hospitality and firm friendship. Richard and Sue Dean were a constant source of inspiration throughout the study and their diligence and enthusiasm in the field is an example to us all. -

Long-Term Growth Patterns of Welwitschia Mirabilis, a Long-Lived Plant of the Namib Desert (Including a Bibliography)

Plant Ecology 150: 7–26, 2000. 7 © 2000 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Long-term growth patterns of Welwitschia mirabilis, a long-lived plant of the Namib Desert (including a bibliography) Joh R. Henschel & Mary K. Seely Desert Ecological Research Unit, Desert Research Foundation of Namibia, Gobabeb Training and Research Centre, P.O. Box 953, Walvis Bay, Namibia (E-mail: [email protected]) Key words: Episodic events, Long-term ecological research, Namibia, Population dynamics, Seasonality, Sex ratio Abstract Over the past 14 years, long-term ecological research (LTER) was conducted on the desert perennial, Welwitschia mirabilis (Gnetales: Welwitschiaceae), located in the Welwitschia Wash near Gobabeb in the Central Namib Desert. We measured leaf growth of 21 plants on a monthly basis and compared this with climatic data. The population structure as well as its spatial distribution was determined for 110 individuals. Growth rate was 0.37 mm day−1, but varied 22-fold within individuals, fluctuating seasonally and varying between years. Seasonal patterns were correlated with air humidity, while annual differences were affected by rainfall. During three years, growth rate quadrupled following episodic rainfall events >11 mm during mid-summer. One natural recruitment event followed a 13-mm rainfall at the end of summer. Fog did not appear to influence growth patterns and germination. Plant loca- tion affected growth rate; plants growing on the low banks, or ledges, of the main drainage channel grew at a higher rate, responded better and longer to rainfall and had relatively larger leaves than plants in the main channel or its tributaries. -

CROWNED CORMORANT | Microcarbo Coronatus (Phalacrocorax Coronatus)

CROWNED CORMORANT | Microcarbo coronatus (Phalacrocorax coronatus) J Kemper | Reviewed by: T Cook; AJ Williams © Jessica Kemper Conservation Status: Near Threatened Southern African Range: Coastal Namibia, South Africa Area of Occupancy: 6,700 km2 Population Estimate: 1,200 breeding pairs in Namibia Population Trend: Stable to slightly increasing Habitat: Coastal islands and rocks, protected mainland sites, artificial structures, inshore marine waters Threats: Disturbance, entanglement in human debris and artificial structures, predation by gulls and seals, pollution from oiling 152 BIRDS TO WATCH IN NAMIBIA DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE TABLE 2.5: A resident species with some juvenile dispersal, this small Number of Crowned Cormorant breeding pairs at individu- cormorant is endemic to south-west Namibia and west al breeding localities in Namibia (listed north to south), esti- to south-western South Africa. It has a very restricted mated from annual peaks of monthly nest counts at Mercu- ry, Ichaboe, Halifax and Possession islands, and elsewhere range along the coastline (Crawford 1997b), occupying an from opportunistic counts, not necessarily done during peak area of about 6,700 km2 in Namibia (Jarvis et al. 2001). It breeding (Bartlett et al. 2003, du Toit et al. 2003, Kemper et usually occurs within one kilometre of the coast, and has al. 2007, MFMR unpubl. data). not been recorded more than 10 km from land (Siegfried et al. 1975). It breeds at numerous localities in Namibia Number of Date of most and South Africa. In Namibia, it is known to breed at 12 breeding recent reliable islands, five mainland localities and one artificial structure, Breeding locality pairs estimate from Bird Rock Guano Platform near Walvis Bay to Sinclair Bird Rock Platform 98 1999/2000 Island (Table 2.5: Bartlett et al. -

The German Colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German Rivalry, 1883-1915

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 7-1-1995 Doors left open then slammed shut: The German colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German rivalry, 1883-1915 Matthew Erin Plowman University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Plowman, Matthew Erin, "Doors left open then slammed shut: The German colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German rivalry, 1883-1915" (1995). Student Work. 435. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/435 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOORS LEFT OPEN THEN SLAMMED SHUT: THE GERMAN COLONIZATION OF SOUTHWEST AFRICA AND THE ANGLO-GERMAN RIVALRY, 1883-1915. A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts University of Nebraska at Omaha by Matthew Erin Plowman July 1995 UMI Number: EP73073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Blsaartalibn Publish*rig UMI EP73073 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

South Africa Mega Birding Tour I 6Th to 30Th January 2018 (25 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding Tour I 6th to 30th January 2018 (25 days) Trip Report Aardvark by Mike Bacon Trip report compiled by Tour Leader: Wayne Jones Rockjumper Birding Tours View more tours to South Africa Trip Report – RBT South Africa - Mega I 2018 2 Tour Summary The beauty of South Africa lies in its richness of habitats, from the coastal forests in the east, through subalpine mountain ranges and the arid Karoo to fynbos in the south. We explored all of these and more during our 25-day adventure across the country. Highlights were many and included Orange River Francolin, thousands of Cape Gannets, multiple Secretarybirds, stunning Knysna Turaco, Ground Woodpecker, Botha’s Lark, Bush Blackcap, Cape Parrot, Aardvark, Aardwolf, Caracal, Oribi and Giant Bullfrog, along with spectacular scenery, great food and excellent accommodation throughout. ___________________________________________________________________________________ Despite havoc-wreaking weather that delayed flights on the other side of the world, everyone managed to arrive (just!) in South Africa for the start of our keenly-awaited tour. We began our 25-day cross-country exploration with a drive along Zaagkuildrift Road. This unassuming stretch of dirt road is well-known in local birding circles and can offer up a wide range of species thanks to its variety of habitats – which include open grassland, acacia woodland, wetlands and a seasonal floodplain. After locating a handsome male Northern Black Korhaan and African Wattled Lapwings, a Northern Black Korhaan by Glen Valentine -

Namibia & the Okavango

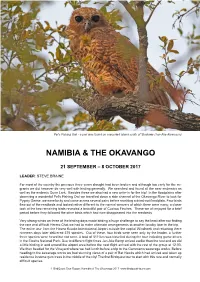

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report

MIOMBO ECOREGION VISION REPORT Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo December 2001 (published 2011) Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 20 WWF - SARPO MIOMBO ECOREGION VISION REPORT 2001 (revised August 2011) by Jonathan Timberlake & Emmanuel Chidumayo Occasional Publications in Biodiversity No. 20 Biodiversity Foundation for Africa P.O. Box FM730, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe PREFACE The Miombo Ecoregion Vision Report was commissioned in 2001 by the Southern Africa Regional Programme Office of the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF SARPO). It represented the culmination of an ecoregion reconnaissance process led by Bruce Byers (see Byers 2001a, 2001b), followed by an ecoregion-scale mapping process of taxa and areas of interest or importance for various ecological and bio-physical parameters. The report was then used as a basis for more detailed discussions during a series of national workshops held across the region in the early part of 2002. The main purpose of the reconnaissance and visioning process was to initially outline the bio-physical extent and properties of the so-called Miombo Ecoregion (in practice, a collection of smaller previously described ecoregions), to identify the main areas of potential conservation interest and to identify appropriate activities and areas for conservation action. The outline and some features of the Miombo Ecoregion (later termed the Miombo– Mopane Ecoregion by Conservation International, or the Miombo–Mopane Woodlands and Grasslands) are often mentioned (e.g. Burgess et al. 2004). However, apart from two booklets (WWF SARPO 2001, 2003), few details or justifications are publically available, although a modified outline can be found in Frost, Timberlake & Chidumayo (2002). Over the years numerous requests have been made to use and refer to the original document and maps, which had only very restricted distribution.