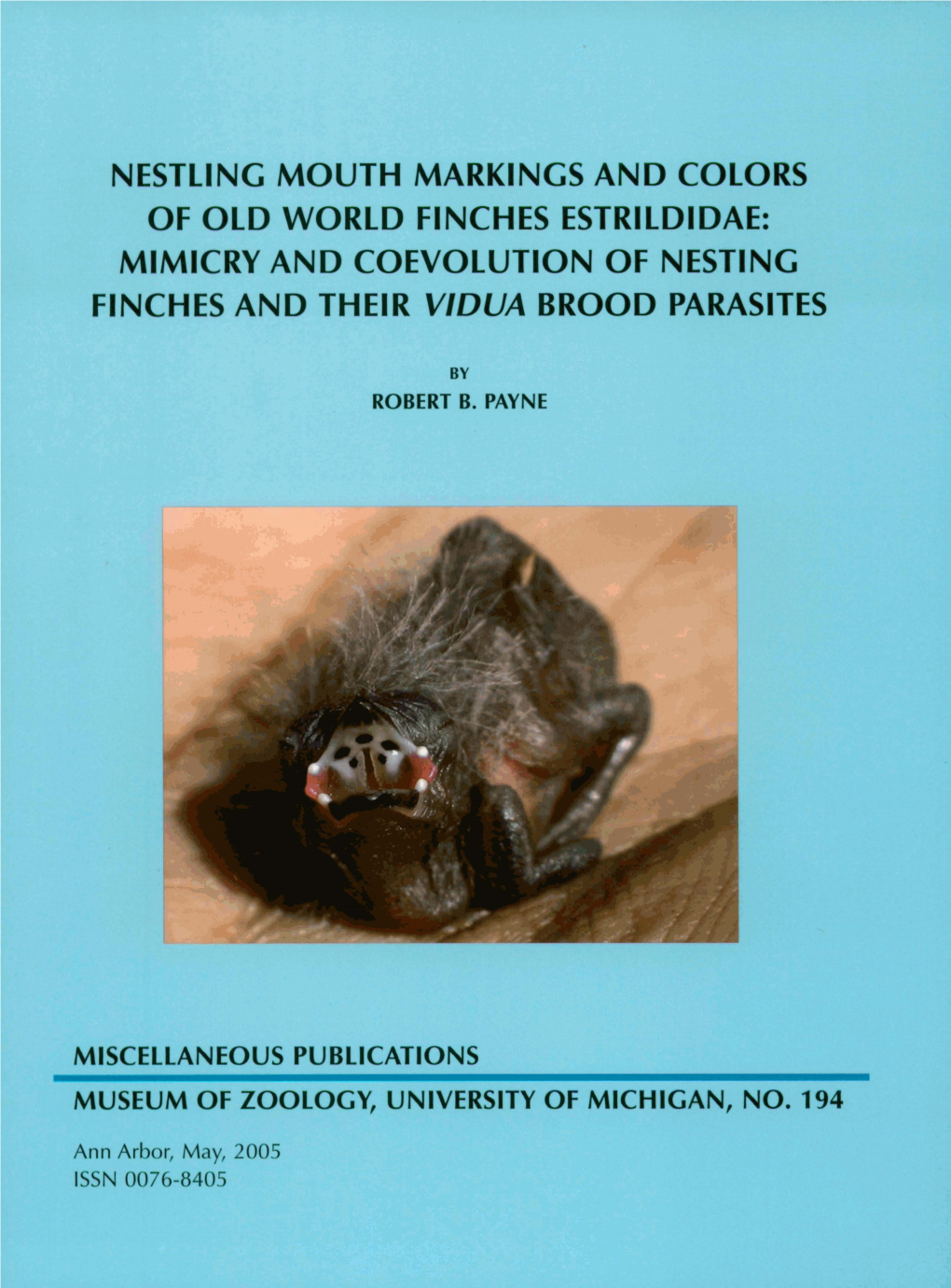

NESTLING MOUTH Marklngs It '" "' of OLD WORLD FINCHES ESTLLU MIMICRY and COEVOLUTION of NESTING

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Avifaunal Impact Assessment: Scoping

AVIFAUNAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT: SCOPING Proposed construction and operation of the 100MW Rondavel Solar Photovoltaic Facility, Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) and associated infrastructure located near Kroonstad in the Free State Province November 2020 Page | 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY South Africa Mainstream Renewable Power Developments (Pty) Ltd is proposing the construction and operation of the 100 MW Rondavel Photovoltaic (PV) Solar Energy Facility (SEF) and Battery Energy Storage System (BESS), near the town of Kroonstad in the Moqhaka Local Municipality (Fezile Dabi District) of the Free State Province of South Africa. The proposed PV facility will be connecting to the grid via a 132kV grid connection, which is the subject of a separate EA. This bird scoping assessment report deals only with the proposed 100 MW Rondavel Solar Photovoltaic (PV) Facility, and the associated infrastructure thereof. 1. Impacts The anticipated impacts were summarized, and a comparison made between pre-and post-mitigation phases as shown in the Table below. The rating of environmental issues associated with different parameters prior to and post mitigation of a proposed activity was averaged. A comparison was then made to determine the effectiveness of the proposed mitigation measures. The comparison identified critical issues related to the environmental parameters. Environmental Issues Anticipated rating prior to Anticipated rating post parameter mitigation mitigation Avifauna Displacement of 40 medium 30 medium priority species due to disturbance associated -

2007 Birds in a Changing Climate

T HE S TATE OF A USTRALIA ’ S B IRDS 2 0 0 7 Birds in a Changing Climate Compiled by Penny Olsen Supplement to Wingspan, vol. 14, no. 4, December 2007 2 The State of Australia’s Birds 2007 The State of Australia’s Birds 2007 3 The term climate change is commonly used to refer to shifts in modern climate, including the rise in average surface temperature known as global warming or the enhanced greenhouse effect. We use it here to refer to anthropogenic climate change, under the presumption that it is overwhelmingly caused by humans and hence has potential to largely be stabilised or reversed. The State of Australia’s Birds report series presents an overview of the status of the nation’s birds, the major threats they face and the conservation actions needed. This fifth annual report focuses on climate change. The climate is always changing and birds respond by adapting and evolving. However, at least since the very early 1900s the surface temperature of the earth has been warming at a rate unprecedented in human history, bringing with it shifts in local, regional and global weather systems. The vast majority of scientists agree that this is almost all attributable to the release of excessive amounts of greenhouse gases through human activity, particularly the use of fossil fuels and deforestation. Australia has warmed by 0.9 ° C since 1900, most rapidly since 1950, and is expected to warm a further 1 ° C over the next two decades. Signs of this change are already reflected in the distribution and abundance of some of our birds and in the timing of their breeding and migration, in line with changes observed in other biota. -

A Bioacoustic Record of a Conservancy in the Mount Kenya Ecosystem

Biodiversity Data Journal 4: e9906 doi: 10.3897/BDJ.4.e9906 Data Paper A Bioacoustic Record of a Conservancy in the Mount Kenya Ecosystem Ciira wa Maina‡§, David Muchiri , Peter Njoroge| ‡ Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, Dedan Kimathi University of Technology, Nyeri, Kenya § Dedan Kimathi University Wildlife Conservancy, Dedan Kimathi University of Technology, Nyeri, Kenya | Ornithology Section, Department of Zoology, National Museums of Kenya, Nairobi, Kenya Corresponding author: Ciira wa Maina ([email protected]) Academic editor: Therese Catanach Received: 17 Jul 2016 | Accepted: 23 Sep 2016 | Published: 05 Oct 2016 Citation: wa Maina C, Muchiri D, Njoroge P (2016) A Bioacoustic Record of a Conservancy in the Mount Kenya Ecosystem. Biodiversity Data Journal 4: e9906. doi: 10.3897/BDJ.4.e9906 Abstract Background Environmental degradation is a major threat facing ecosystems around the world. In order to determine ecosystems in need of conservation interventions, we must monitor the biodiversity of these ecosystems effectively. Bioacoustic approaches offer a means to monitor ecosystems of interest in a sustainable manner. In this work we show how a bioacoustic record from the Dedan Kimathi University wildlife conservancy, a conservancy in the Mount Kenya ecosystem, was obtained in a cost effective manner. A subset of the dataset was annotated with the identities of bird species present since they serve as useful indicator species. These data reveal the spatial distribution of species within the conservancy and also point to the effects of major highways on bird populations. This dataset will provide data to train automatic species recognition systems for birds found within the Mount Kenya ecosystem. -

A Report on a Community Partnership in Eco-Acoustic Monitoring in Brisbane Ranges National Park, Victoria

Australian Owlet-nightjar. Photo: Damian Kelly A REPORT ON A COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIP IN ECO-ACOUSTIC MONITORING IN BRISBANE RANGES NATIONAL PARK, VICTORIA Prepared by: Dr Sera Blair, Christine Connelly, Caitlin Griffith, Victorian National Parks Association. Dr Karen Rowe & Dr Amy Adams, Museums Victoria Victorian National Parks Association The Victorian National Parks Association (VNPA) helps to shape the agenda for creating and managing national parks, conservation reserves and other important natural areas across land and sea. We work with all levels of government, the scientific community and the general community to achieve long term, best practice environmental outcomes. The VNPA is also Victoria’s largest bush walking club and provides a range of information, education and activity programs to encourage Victorians to get active for nature. NatureWatch NatureWatch is a citizen science program which engages the community in collecting scientific data on Victorian native plants and animals. The program builds links between community members, scientists and land managers to develop scientific, practical projects that contribute to a better understanding of species and ecosystems, and contributes to improved management of natural areas. Project Partners Museums Victoria Museums Victoria has been trusted with the collection and curation of Victoria’s natural history for over 160 years and serves as a key international research institute and experts in data archiving and long- term data protection. Responding to changing intellectual issues, studying subjects of relevance to the community, providing training and professional development, and working closely with schools, communities, and online visitors, Museums Victoria works to disseminate our collective knowledge through online resources and image, audio and video databases. -

OIK-02296 Ferger, SW, Dulle, HI, Schleuning, M

Oikos OIK-02296 Ferger, S. W., Dulle, H. I., Schleuning, M. and Böhning- Gaese, K: 2015. Frugivore diversity increases frugivory rates along a large elevational gradient. – Oikos doi: 10.1111/oik.02296 Appendix 1. Map of Mt Kilimanjaro showing the location of the 64 study plots in 13 different habitat types. Appendix 2. List of all 187 bird species that were observed, their average body mass and their feeding guild. Appendix 3. Effect of bird abundance/richness and fruit color on the proportion of pecked vs. unpecked artificial fruits without controlling for vertical vegetation heterogeneity and natural fruit abundance. Appendix 4. Effect of vertical vegetation heterogeneity, natural fruit abundance and fruit color on the proportion of pecked versus unpecked artificial fruits. 1 Appendix 1 Map of Mount Kilimanjaro showing the location of the 64 study plots in 13 different habitat types. The near-natural habitat types are savannah (sav), lower montane forest (flm), Ocotea forest (foc), Podocarpus forest (fpo), Erica forest (fer) and Helichrysum scrub (hel). The disturbed habitat types are maize field (mai), Chagga homegarden (hom), shaded coffee plantation (cof), unshaded coffee plantation (sun), grassland (gra), disturbed Ocotea forest (fod) and disturbed Podocarpus forest (fpd). Each habitat type is represented by five replicate plots, except for the unshaded coffee plantation, which is covered by four replicate plots. One of these five (respectively four) plots per habitat type is used as ‘focal plot’ (yellow squares) for especially labor-intensive studies like the artificial fruits experiment presented in this study. As background map, we used the National Geographic World Map developed by National Geographic and Esri (<http://goto.arcgisonline.com/maps/NatGeo_World_Map>). -

The Birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an Annotated Checklist

European Journal of Taxonomy 306: 1–69 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.306 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Gedeon K. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. Monograph urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:A32EAE51-9051-458A-81DD-8EA921901CDC The birds (Aves) of Oromia, Ethiopia – an annotated checklist Kai GEDEON 1,*, Chemere ZEWDIE 2 & Till TÖPFER 3 1 Saxon Ornithologists’ Society, P.O. Box 1129, 09331 Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Germany. 2 Oromia Forest and Wildlife Enterprise, P.O. Box 1075, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia. 3 Zoological Research Museum Alexander Koenig, Centre for Taxonomy and Evolutionary Research, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F46B3F50-41E2-4629-9951-778F69A5BBA2 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F59FEDB3-627A-4D52-A6CB-4F26846C0FC5 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A87BE9B4-8FC6-4E11-8DB4-BDBB3CFBBEAA Abstract. Oromia is the largest National Regional State of Ethiopia. Here we present the first comprehensive checklist of its birds. A total of 804 bird species has been recorded, 601 of them confirmed (443) or assumed (158) to be breeding birds. At least 561 are all-year residents (and 31 more potentially so), at least 73 are Afrotropical migrants and visitors (and 44 more potentially so), and 184 are Palaearctic migrants and visitors (and eight more potentially so). Three species are endemic to Oromia, 18 to Ethiopia and 43 to the Horn of Africa. 170 Oromia bird species are biome restricted: 57 to the Afrotropical Highlands biome, 95 to the Somali-Masai biome, and 18 to the Sudan-Guinea Savanna biome. -

South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park Custom Tour Trip Report

SOUTH AFRICA: MAGOEBASKLOOF AND KRUGER NATIONAL PARK CUSTOM TOUR TRIP REPORT 24 February – 2 March 2019 By Jason Boyce This Verreaux’s Eagle-Owl showed nicely one late afternoon, puffing up his throat and neck when calling www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT South Africa: Magoebaskloof and Kruger National Park February 2019 Overview It’s common knowledge that South Africa has very much to offer as a birding destination, and the memory of this trip echoes those sentiments. With an itinerary set in one of South Africa’s premier birding provinces, the Limpopo Province, we were getting ready for a birding extravaganza. The forests of Magoebaskloof would be our first stop, spending a day and a half in the area and targeting forest special after forest special as well as tricky range-restricted species such as Short-clawed Lark and Gurney’s Sugarbird. Afterwards we would descend the eastern escarpment and head into Kruger National Park, where we would make our way to the northern sections. These included Punda Maria, Pafuri, and the Makuleke Concession – a mouthwatering birding itinerary that was sure to deliver. A pair of Woodland Kingfishers in the fever tree forest along the Limpopo River Detailed Report Day 1, 24th February 2019 – Transfer to Magoebaskloof We set out from Johannesburg after breakfast on a clear Sunday morning. The drive to Polokwane took us just over three hours. A number of birds along the way started our trip list; these included Hadada Ibis, Yellow-billed Kite, Southern Black Flycatcher, Village Weaver, and a few brilliant European Bee-eaters. -

The Crimson Finch

PUBLISHED FOR BIRD LOVERS BY BIRD LOVERS life Aviarywww.aviarylife.com.au Issue 04/2015 $12.45 Incl. GST Australia The Red Strawberry Finch Crimson Finch Black-capped Lory One Week in Brazil The Red-breasted Goose ISSN 1832-3405 White-browed Woodswallow The Crimson Finch A Striking Little Aussie! Text by Glenn Johnson Photos by Julian Robinson www.flickr.com/photos/ozjulian/ Barbara Harris www.flickr.com/photos/12539790@N00/ Jon Irvine www.flickr.com/photos/33820263@N07/ and Aviarylife. Introduction he Crimson Finch Neochmia phaeton has Talways been one of the rarer Australian finches in captivity, and even more so since the white- the mid-late 1980’s, when the previously legal bellied. The trapping of wild finches in Australia was crown is dark prohibited across all states. They unfortunately brown, the back and have a bad reputation for being aggressive, wings are paler brown washed with red, the tail and this together with the fact that they is long, scarlet on top and black underneath. are reasonably expensive in comparison to The cheeks along with the entire under parts are many other finches, could well be a couple deep crimson, the flanks are spotted white, and of the main reasons as to why they are not so the centre of the belly is black in the nominate commonly kept. race and white for N. p. evangelinae, and the Description beak is red. Hens are duller, with black beaks. They are an elegant bird, generally standing There are two types of Crimson Finches, the very upright on the perch, and range from 120- black-bellied, which is the nominate form and 140mm in length. -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Ghana

Avibase Page 1of 24 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Ghana 2 Number of species: 773 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 26 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2019-11-10 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Ghana. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=gh [26/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Birders Checklist for the Mapungubwe National Park and Area

Birders Checklist for the Mapungubwe National Park and area Reproduced with kind permission of Etienne Marais of Indicator Birding Visit www.birding.co.za for more info and details of birding tours and events Endemic birds KEY: SA = South African Endemic, SnA = Endemic to Southern Africa, NE = Near endemic (Birders endemic) to the Southern African Region. RAR = Rarity Status KEY: cr = common resident; nr = nomadic breeding resident; unc = uncommon resident; rr = rare; ? = status uncertain; s = summer visitor; w = winter visitor r Endemicity Numbe Sasol English Status All Scientific p 30 Little Grebe cr Tachybaptus ruficollis p 30 Black-necked Grebe nr Podiceps nigricollis p 56 African Darter cr Anhinga rufa p 56 Reed Cormorant cr Phalacrocorax africanus p 56 White-breasted Cormorant cr Phalacrocorax lucidus p 58 Great White Pelican nr Pelecanus onocrotalus p 58 Pink-backed Pelican ? Pelecanus rufescens p 60 Grey Heron cr Ardea cinerea p 60 Black-headed Heron cr Ardea melanocephala p 60 Goliath Heron cr Ardea goliath p 60 Purple Heron uncr Ardea purpurea p 62 Little Egret uncr Egretta garzetta p 62 Yellow-billed Egret uncr Egretta intermedia p 62 Great Egret cr Egretta alba p 62 Cattle Egret cr Bubulcus ibis p 62 Squacco Heron cr Ardeola ralloides p 64 Black Heron uncs Egretta ardesiaca p 64 Rufous-bellied Heron ? Ardeola rufiventris RA p 64 White-backed Night-Heron rr Gorsachius leuconotus RA p 64 Slaty Egret ? Egretta vinaceigula p 66 Green-backed Heron cr Butorides striata p 66 Black-crowned Night-Heron uncr Nycticorax nycticorax p -

Namibia & the Okavango

Pel’s Fishing Owl - a pair was found on a wooded island south of Shakawe (Jan-Ake Alvarsson) NAMIBIA & THE OKAVANGO 21 SEPTEMBER – 8 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: STEVE BRAINE For most of the country the previous three years drought had been broken and although too early for the mi- grants we did however do very well with birding generally. We searched and found all the near endemics as well as the endemic Dune Lark. Besides these we also had a new write-in for the trip! In the floodplains after observing a wonderful Pel’s Fishing Owl we travelled down a side channel of the Okavango River to look for Pygmy Geese, we were lucky and came across several pairs before reaching a dried-out floodplain. Four birds flew out of the reedbeds and looked rather different to the normal weavers of which there were many, a closer look at the two remaining birds revealed a beautiful pair of Cuckoo Finches. These we all enjoyed for a brief period before they followed the other birds which had now disappeared into the reedbeds. Very strong winds on three of the birding days made birding a huge challenge to say the least after not finding the rare and difficult Herero Chat we had to make alternate arrangements at another locality later in the trip. The entire tour from the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside the capital Windhoek and returning there nineteen days later delivered 375 species. Out of these, four birds were seen only by the leader, a further three species were heard but not seen. -

Detailed Itinerary

Title: Ethiopia Birding Tour-14 days Accommodation: Hotels and Lodges Transportation: Drive Duration: 14 Days/13 Nights Number of PAX: 2-12 SHORT DESCRIPTION Our two weeks trip starts from the capital, Addis Ababa, spotting the endemic Wattled Ibis. In Addis Ababa,thick-billed raven, White-collared Pigeon, the beautiful Abyssinian Longclaw, and more can also be seen. 211km from Addis is Awash National Park. The park preserves Beisa oryx, Kudu, Soemmerring's gazelle, Swayne’s hartebeest, Olive and hamadryas baboons, colobus and grivet monkeys, and Dik-dik. This trip will also take us to the hotsprings of Doho. We will also encounter the endemic birds such as, Blue-winged Goose, Spot breasted lapwing, Yellow fronted parrot, Abyssinian longclaw, Abyssinian catbird, and Black-headed siskin. Ethiopian Wolf, Mountain Nyala, Bale Monkey, Menelik’s Bushbuck, and Starck’s Hare can also be seen in Bale Mountain. The enigmatic Stresemann’s bush crow and glistening White-tailed swallow are seen in Yabello Wildlife Sanctuary. Birding at the Ethiopian Great Rift Valley lakes is also part of this package. DETAILED ITINERARY Day 1: Arrival in Addis Ababa and touring The tour starts with a pick up from the airport/hotel, and then drive up to the Entoto Mountains, the best location to observe the panoramic view of the capital. It is also a historical place where Menelik II resided and built his palace. It is notable as the location of a number of celebrated churches, including Saint Raguel and Saint Mary (Maryam Church). After a relaxed lunch, you will have Birding in the ground of Ghion Hotel and find wide enchanting gardens filled with indigenous flora and a stunning collection of birds including the endemic Wattled Ibis.