Synthesis Report for Characterization of Communal Grasslands in Menz and Abergele in Ethiopia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Local History of Ethiopia an - Arfits © Bernhard Lindahl (2005)

Local History of Ethiopia An - Arfits © Bernhard Lindahl (2005) an (Som) I, me; aan (Som) milk; damer, dameer (Som) donkey JDD19 An Damer (area) 08/43 [WO] Ana, name of a group of Oromo known in the 17th century; ana (O) patrikin, relatives on father's side; dadi (O) 1. patience; 2. chances for success; daddi (western O) porcupine, Hystrix cristata JBS56 Ana Dadis (area) 04/43 [WO] anaale: aana eela (O) overseer of a well JEP98 Anaale (waterhole) 13/41 [MS WO] anab (Arabic) grape HEM71 Anaba Behistan 12°28'/39°26' 2700 m 12/39 [Gz] ?? Anabe (Zigba forest in southern Wello) ../.. [20] "In southern Wello, there are still a few areas where indigenous trees survive in pockets of remaining forests. -- A highlight of our trip was a visit to Anabe, one of the few forests of Podocarpus, locally known as Zegba, remaining in southern Wello. -- Professor Bahru notes that Anabe was 'discovered' relatively recently, in 1978, when a forester was looking for a nursery site. In imperial days the area fell under the category of balabbat land before it was converted into a madbet of the Crown Prince. After its 'discovery' it was declared a protected forest. Anabe is some 30 kms to the west of the town of Gerba, which is on the Kombolcha-Bati road. Until recently the rough road from Gerba was completed only up to the market town of Adame, from which it took three hours' walk to the forest. A road built by local people -- with European Union funding now makes the forest accessible in a four-wheel drive vehicle. -

Effects of Fertilization and Harvesting Age on Yield and Quality of Desho

Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries 2020; 9(4): 113-121 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/aff doi: 10.11648/j.aff.20200904.13 ISSN: 2328-563X (Print); ISSN: 2328-5648 (Online) Effects of Fertilization and Harvesting Age on Yield and Quality of Desho (Pennisetum pedicellatum ) Grass Under Irrigation, in Dehana District, Wag Hemra Zone, Ethiopia Awoke Kefyalew 1, Berhanu Alemu 2, Alemu Tsegaye 3 1Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture, Oda Bultum University, Chiro, Ethiopia 2Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Debre Markos University, Debre Markos, Ethiopia 3Sekota Dry Land Agricultural Research Center, Sekota, Ethiopia Email address: To cite this article: Awoke Kefyalew, Berhanu Alemu, Alemu Tsegaye. Effects of Fertilization and Harvesting Age on Yield and Quality of Desho (Pennisetum pedicellatum ) Grass Under Irrigation, in Dehana District, Wag Hemra Zone, Ethiopia. Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries . Vol. 9, No. 4, 2020, pp. 113-121. doi: 10.11648/j.aff.20200904.13 Received : June 5, 2020; Accepted : June 19, 2020; Published : July 28, 2020 Abstract: The experiment was conducted to evaluating the effects of fertilizer and harvesting age on agronomic performance, chemical composition and economic feasibility of Desho (Pennisetum Pedicellatum) grass under irrigation, in Ethiopia. A factorial arrangement with four fertilizer types (control, urea, compost and urea + compost), and three harvesting ages (90, 120 and 150) with three replications were used. Data on morphological characteristics of the grass were recorded. Based on the data collected, harvesting age was significantly affected the agronomic parameters of the grass. Plant height (PH), number of tillers per plant (NTPP), number of leaves per plant (NLPP), number of leaves per tiller (NLPT), dry matter yield (DMY), leaf length (LL) and leaf area (LA) were increased with increasing harvesting age, while leaf to stem ratio (LSR) showed a decreasing trend. -

Ethnobotany, Diverse Food Uses, Claimed Health Benefits And

Shewayrga and Sopade Journal of Ethnobiology and Ethnomedicine 2011, 7:19 http://www.ethnobiomed.com/content/7/1/19 JOURNAL OF ETHNOBIOLOGY AND ETHNOMEDICINE RESEARCH Open Access Ethnobotany, diverse food uses, claimed health benefits and implications on conservation of barley landraces in North Eastern Ethiopia highlands Hailemichael Shewayrga1* and Peter A Sopade2,3 Abstract Background: Barley is the number one food crop in the highland parts of North Eastern Ethiopia produced by subsistence farmers grown as landraces. Information on the ethnobotany, food utilization and maintenance of barley landraces is valuable to design and plan germplasm conservation strategies as well as to improve food utilization of barley. Methods: A study, involving field visits and household interviews, was conducted in three administrative zones. Eleven districts from the three zones, five kebeles in each district and five households from each kebele were visited to gather information on the ethnobotany, the utilization of barley and how barley end-uses influence the maintenance of landrace diversity. Results: According to farmers, barley is the “king of crops” and it is put for diverse uses with more than 20 types of barley dishes and beverages reportedly prepared in the study area. The products are prepared from either boiled/roasted whole grain, raw- and roasted-milled grain, or cracked grain as main, side, ceremonial, and recuperating dishes. The various barley traditional foods have perceived qualities and health benefits by the farmers. Fifteen diverse barley landraces were reported by farmers, and the ethnobotany of the landraces reflects key quantitative and qualitative traits. Some landraces that are preferred for their culinary qualities are being marginalized due to moisture shortage and soil degradation. -

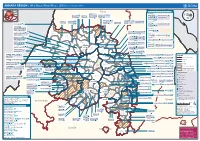

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Abbysinia/Ethiopia: State Formation and National State-Building Project

Abbysinia/Ethiopia: State Formation and National State-Building Project Comparative Approach Daniel Gemtessa Oct, 2014 Department of Political Sience University of Oslo TABLE OF CONTENTS No.s Pages Part I 1 1 Chapter I Introduction 1 1.1 Problem Presentation – Ethiopia 1 1.2 Concept Clarification 3 1.2.1 Ethiopia 3 1.2.2 Abyssinia Functional Differentiation 4 1.2.3 Religion 6 1.2.4 Language 6 1.2.5 Economic Foundation 6 1.2.6 Law and Culture 7 1.2.7 End of Zemanamesafint (Era of the Princes) 8 1.2.8 Oromos, Functional Differentiation 9 1.2.9 Religion and Culture 10 1.2.10 Law 10 1.2.11 Economy 10 1.3 Method and Evaluation of Data Materials 11 1.4 Evaluation of Data Materials 13 1.4.1 Observation 13 1.4.2 Copyright Provision 13 1.4.3 Interpretation 14 1.4.4 Usability, Usefulness, Fitness 14 1.4.5 The Layout of This Work 14 Chapter II Theoretical Background 15 2.1 Introduction 15 2.2 A Short Presentation of Rokkan’s Model as a Point of Departure for 17 the Overall Problem Presentation 2.3 Theoretical Analysis in Four Chapters 18 2.3.1 Territorial Control 18 2.3.2 Cultural Standardization 18 2.3.3 Political Participation 19 2.3.4 Redistribution 19 2.3.5 Summary of the Theory 19 Part II State Formation 20 Chapter III 3 Phase I: Penetration or State Formation Process 20 3.0.1 First: A Short Definition of Nation 20 3.0.2 Abyssinian/Ethiopian State Formation Process/Territorial Control? 21 3.1 Menelik (1889 – 1913) Emperor 21 3.1.1 Introduction 21 3.1.2 The Colonization of Oromo People 21 3.2 Empire State Under Haile Selassie, 1916 – 1974 37 -

Development Food Assistance Program (DFAP) Fiscal

Food for the Hungry Ethiopia Title II - Development Food Assistance Program (DFAP) Fiscal Year 2016 Annual Results Report Award Number: AID-FFP-A-11-00012 Submission Date: November 21, 2016 Re-Submission Date: March xx, 2017 FH HQ CONTACT FH/ETHIOPIA CONTACT Anthony Koomson Craig Jaggers Global Director, Public Resources Development Country Director Food for the Hungry P.O. Box: 4181 1001 Connecticut Ave. NW Suite 1115 Addis Ababa Washington, DC 20036 Ethiopia Tel: 202-683-7577 Tel: 251-016-188461 Fax: 202-547-0523 Fax: 251-016-188482 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................IV 1. UPLOADS TO FFPMIS .......................................................................................................... 1 A. ANNUAL RESULTS REPORT (ARR) NARRATIVE 1 I) PROJECT ACTIVITIES AND RESULTS ............................................................................................................................ 1 SO 1: HEALTH AND NUTRITION OF WOMEN AND UNDER FIVE CHILDREN IMPROVED 1 SO 2: COMMUNITY RESILIENCY TO WITHSTAND SHOCKS IMPROVED 9 II) DIRECT PARTICIPANTS BY STRATEGIC OBJECTIVE/PURPOSE .............................................................................. 19 III) CHALLENGES, SUCCESSES, AND LESSONS LEARNED ........................................................................................... 19 B. SUCCESS STORIES 20 C. INDICATOR PERFORMANCE TRACKING TABLE (IPTT) 20 D. INDICATOR -

Evaluation Report

EVALUATION REPORT Program for Emergency Seed support (PESS) project in Wag Himra Zone of Amhara Region Submitted to Food for the Hungry (FH) Karamara Consultancy Service Samuel Lemma February 2021 +251 911 455938; +251 922 785412; +251 984 000804 Addis Ababa Website: http://www.karamaraconsultancy.com Email: [email protected]; [email protected] P.O. Box 4674, Addis Ababa, Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENT........................................................................................................... iv ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................. v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... vi 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 2. PURPOSE AND OBJECTIVES OF THE EVALUATION............................................... 3 2.1 Purpose and general objectives of the Evaluation.......................................................... 3 2.2 Specific Objectives: ....................................................................................................... 3 3. SCOPE OF THE EVALUATION ...................................................................................... 3 3.1 Programme Focus........................................................................................................... 3 3.2 Geographical Focus ....................................................................................................... -

Comparative Performance Evaluation of Horro and Menz Sheep of Ethiopia Under Grazing and Intensive Feeding Conditions

Institut für Nutztierwissenschaften der Landwirtschaftlich-Gärtnerischen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin DISSERTATION Comparative performance evaluation of Horro and Menz sheep of Ethiopia under grazing and intensive feeding conditions Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades doctor rerum agriculturarum (Dr. rer. agr.) eingereicht an der Landwirtschaftlich-Gärtnerischen Fakultät der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin von Kassahun Awgichew (M.Sc., Animal Science, University of Wales, UK) Präsident der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin Prof. Dr. Jürgen Mlynek Dekan der Landwirtschaftlich-Gärtnerischen Fakultät Prof. Dr. Dr. h. c. E. Lindmann Vorsitzender der Prüfungskommission Prof. Dr. Konrad Hagedorn Gutachter:1. Prof. Dr. K. J. Peters 2. Prof. Dr. G. Seeland weitere Mitglieder der Prüfungskommission 1. Dr. Claudia Kijora 2. Dr. T. Hardge Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 20. 12. 2000 II Dedication This work is dedicated to my parents; my father Ato Awgichew Ayalew and my mother Woizero Elfinesh Kidanemariam and to my wife Woizero Etabezahu Eshetu and our children Henok, Mahlet and Bezaye. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS III ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest respect and most sincere gratitude to my supervisor, Prof. Dr. K. J. Peters, for his guidance and encouragement at all stages of my work. His constructive criticism and comments from the initial conception to the end of this work is highly appreciated. I am greatly indebted to his assistance and understanding in matters of non academic concern which have helped me endure some difficult times during my study period. I am thankful to Prof. Dr. G. Seeland for willingly accepting to evaluate my Thesis and sit in the examination committee. I thank Dr. T. -

Behavior of Geladas and Other Endemic Wildlife During a Desert Locust Outbreak at Guassa, Ethiopia: Ecological and Conservation Implications

Primates (2010) 51:193–197 DOI 10.1007/s10329-010-0194-6 NEWS AND PERSPECTIVES Behavior of geladas and other endemic wildlife during a desert locust outbreak at Guassa, Ethiopia: ecological and conservation implications Peter J. Fashing • Nga Nguyen • Norman J. Fashing Received: 27 January 2010 / Accepted: 16 February 2010 / Published online: 24 March 2010 Ó Japan Monkey Centre and Springer 2010 Abstract Desert locust (Schistocerca gregaria) outbreaks locust control strategies and potential unintended adverse have occurred repeatedly throughout recorded history in effects on endemic and endangered wildlife. the Horn of Africa region, devastating crops and contrib- uting to famines. In June 2009, a desert locust swarm Keywords Desert locust Á Diet Á Ethiopian wolf Á invaded the Guassa Plateau, Ethiopia, a large and unusually Gelada Á Global warming Á Guassa Á Locust control Á intact Afroalpine tall-grass ecosystem, home to important Pesticide Á Thick-billed raven populations of geladas (Theropithecus gelada), Ethiopian wolves (Canis simensis), thick-billed ravens (Corvus crassirostris), and other Ethiopian or Horn of Africa en- Introduction demics. During the outbreak and its aftermath, we observed many animals, including geladas, ravens, and a wolf, Desert locusts (Schistocerca gregaria) have a long history feeding on locusts in large quantities. These observations of devastating crops and contributing to famines across suggest surprising flexibility in the normally highly spe- southwest Asia, the Middle East, and northern Africa (van cialized diets of geladas and wolves, including the potential Huis 1995). Generally solitary and occurring at low den- for temporary but intensive insectivory during locust out- sities, desert locusts occasionally become gregarious fol- breaks. -

Gender, HIV/AIDS and Food Security Linkage and Integration Into Development Interventions DCG Report No. 32

Gender, HIV/AIDS and Food Security Linkage and Integration into Development Interventions By Dawit Kebede and Solomon Retta December 2004 DCG Report No. 32 Gender, HIV/AIDS and Food Security Linkage and Integration into Development Interventions Dawit Kebede and Solomon Retta DCG Report No. 32 December 2004 The Drylands Coordination Group (DCG) is an NGO-driven forum for exchange of practical experiences and knowledge on food security and natural resource management in the drylands of Africa. DCG facilitates this exchange of experiences between NGOs and research and policy- making institutions. The DCG activities, which are carried out by DCG members in Ethiopia, Eritrea, Mali and Sudan, aim to contribute to improved food security of vulnerable households and sustainable natural resource management in the drylands of Africa. The founding DCG members consist of ADRA Norway, CARE Norway, Norwegian Church Aid, Norwegian People's Aid and The Development Fund. Noragric, the Centre for International Environment and Development Studies at the Agricultural University of Norway, provides the secretariat as a facilitating and implementing body for the DCG. The DCG’s activities are funded by NORAD (the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation). Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the DCG secretariat. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are entirely those of the author(s) and cannot be attributed directly to the Drylands Coordination Group. D. Kebede and S. Retta. Drylands Coordination Group Report No. 32 (12, 2004) Drylands Coordination Group c/o Noragric P.O. Box 5003 N-1432 Ås Norway Tel.: +47 64 94 98 23 Fax: +47 64 94 07 60 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: http://www.drylands-group.org ISSN: 1503-0601 Photo credits: T.A. -

Women and Warfare in Ethiopia

ISSN 1908-6295 Women and Warfare in Ethiopia Minale Adugna Gender Issues Research Report Series - no. 13 Organization for Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa Women and Warfare in Ethiopia A Case Study of Their Role During the Campaign of Adwa, 1895/96, and the Italo-Ethiopian War, 1935-41 Minale Adugna Organization for Social Science Research in Eastern and Southern Africa Gender Issues Research report Series - no. 13 CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................................................... v Acknowledgements............................................................................................ vi Abstract ............................................................................................................. 1 1. Women and War in Ethiopia: From Early Times to the Late 19th Century 1 1.1 The Role of Women in Mobilization ...................................................... 2 1.2 The Role of Women at Battlefields ........................................................ 7 2. The Role of Women during the Campaign of Adwa, 1895/96 ......................... 13 2.1 Empress Taitu and the Road to Adwa .................................................... 13 2.2 The Role of Women at the Battle of Adwa ............................................ 19 3. The Ethiopian Women and the Italio-Ethiopian War, 1935-41 ........................ 21 4. The Impact of War on the Life of Ethiopian Women ....................................... 33 References ........................................................................................................