Criteria for the Evaluation of High School English Compostion By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auburn 1990 Allen Ludden Memorial April 6-7,1990 TOL Gerald

Auburn 1990 Allen Ludden Memorial April 6-7,1990 TOL Gerald Feinberg of Columbia University named it after a Greek word meaning "swift". It's existence J remains a possibility because of a loophole in Einstein's theory of relativity that says no material object can reach the speed of lighL Therefore, a particle could travel faster than the speed of light as long as it didn't slow down. For 10 points' name this theoretical hyper-C particle. ANS: Tachyon T02. Born in 1450' this artist is most famous for his religious allegories. For 10 points name this Flemish painter of The Crowning With Thorns and Garden of Earthlv Delil!hts. ANS: Hieronymus Bosch T03. This battle occurred on May 31, 1916. Controversial due to the number of British losses, the British / Commander, Admiral Jellicoe allowed an outnumbered German fleet to escape in the fog. For 10 points, name this naval engagement which occurred off the coast of Denmark. ANS:Jutland T04. He defeated" 40,000 Frenchmen in 40 minutes" at Salamanca in 1812. This and other victories helped him end _t~f,Peninsula War. As Prime Minister, he was responsible for Catholic Emancipation. But he is undoub~known best for one victory in 1815. For 10 points, by what title do we best know Arthur Wellesley. ANS: Duke of Wellington T05. He won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1919 with The Magnificent Ambersons. In 1922 he became the first to win twice when he won with Alice Adams. For 10 points' name this Pulitzer Prize winning author. -

Available Videos for TRADE (Nothing Is for Sale!!) 1

Available Videos For TRADE (nothing is for sale!!) 1/2022 MOSTLY GAME SHOWS AND SITCOMS - VHS or DVD - SEE MY “WANT LIST” AFTER MY “HAVE LIST.” W/ O/C means With Original Commercials NEW EMAIL ADDRESS – [email protected] For an autographed copy of my book above, order through me at [email protected]. 1966 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS and NBC Fall Schedule Preview 1997 CBS Fall Schedule Preview 1969 CBS Fall Schedule Preview (not for trade) Many 60's Show Promos, mostly ABC Also, lots of Rock n Roll movies-“ROCK ROCK ROCK,” “MR. ROCK AND ROLL,” “GO JOHNNY GO,” “LET’S ROCK,” “DON’T KNOCK THE TWIST,” and more. **I ALSO COLLECT OLD 45RPM RECORDS. GOT ANY FROM THE FIFTIES & SIXTIES?** TV GUIDES & TV SITCOM COMIC BOOKS. SEE LIST OF SITCOM/TV COMIC BOOKS AT END AFTER WANT LIST. Always seeking “Dick Van Dyke Show” comic books and 1950s TV Guides. Many more. “A” ABBOTT & COSTELLO SHOW (several) (Cartoons, too) ABOUT FACES (w/o/c, Tom Kennedy, no close - that’s the SHOW with no close - Tom Kennedy, thankfully has clothes. Also 1 w/ Ben Alexander w/o/c.) ACADEMY AWARDS 1974 (***not for trade***) ACCIDENTAL FAMILY (“Making of A Vegetarian” & “Halloween’s On Us”) ACE CRAWFORD PRIVATE EYE (2 eps) ACTION FAMILY (pilot) ADAM’S RIB (2 eps - short-lived Blythe Danner/Ken Howard sitcom pilot – “Illegal Aid” and rare 4th episode “Separate Vacations” – for want list items only***) ADAM-12 (Pilot) ADDAMS FAMILY (1ST Episode, others, 2 w/o/c, DVD box set) ADVENTURE ISLAND (Aussie kid’s show) ADVENTURER ADVENTURES IN PARADISE (“Castaways”) ADVENTURES OF DANNY DEE (Kid’s Show, 30 minutes) ADVENTURES OF HIRAM HOLLIDAY (8 Episodes, 4 w/o/c “Lapidary Wheel” “Gibraltar Toad,”“ Morocco,” “Homing Pigeon,” Others without commercials - “Sea Cucumber,” “Hawaiian Hamza,” “Dancing Mouse,” & “Wrong Rembrandt”) ADVENTURES OF LUCKY PUP 1950(rare kid’s show-puppets, 15 mins) ADVENTURES OF A MODEL (Joanne Dru 1956 Desilu pilot. -

Stetson 1990 Allen Ludden Memorial April 6-7, 1990 TOL "Our

Stetson 1990 Allen Ludden Memorial April 6-7, 1990 TOL "Our revels now are ended. These actors are melted into air. The solemn temples, the great globe itself shall dissolve; And, like this insubstantial pageant faded, leave not a rack behind." FOR TEN POINTS, the remnan of what English place of presentation has recently been excavated and shown not to have lost all 0 e gifts of Shakespearean theater? GLOBE THEATER T02. It sounds like it may come from llege campus among studen oups, but it doesn't: "Beware of Greeks bearing gifts." FOR TEN ds come from what piece by Virgil? T03. ork City put on display the painting "Le Bateau" (LAY BA-TOW), only problem was th his rk measuring 56 inches by 44 inches was hung upside down. The mistake was not covered fo 47 days. FOR TEN POINTS, this work was o lived 1869-1954. HENRI MATISSE T04. Formerly known the Gold Coast, this Bation contains the co uence of the Black Volta and the White Volta . ers. It is a member of the British Commonwea . FOR TEN POINTS, name this African tion whose capital is Accra. GHANA T05. Herbert Hoover. Alfred Landon. Wendell Wilkie. Thomas Dewey. Other than party affiliation, these men all have what in common, FOR TEN POINTS, in U.S. politics? / ALL WERE DEFEATED BY FRANKLIN ROOSEVELT FOR PRESIDENT T06. They are formed in plants and regulate plant growth. Two specific types are auxins and gibberillins. FOR TEN POINTS, what is this class of substances? / HORMONES T07. "A little learning is a dangerous thing." "Let such teach others who themselves excel." "To err is human, to forgive is divine." Each of these well-known words are taken from a work. -

November 2020

November 2020 Watch our pre-election special November 2 at 8:00 p.m. www.channelpittsburgh.org Changes May Occur | Actual Times May Vary Depending On The Viewing Device WEEKDAYS SATURDAY SUNDAY 7AM To Morning Music Show 9AM 9AM Home on the Read to Me Range Lux Radio 10AM The Singing You are There School Days Cowboy Streets Smart 11AM Roy Rogers Movie Serial Bowl & Trigger 12PM Wylie Ave Matinee Movie Backlot Bijou Theater 1PM General Audiences Heroes of the West The Big Picture 2PM TelePlay Billy the Kid People & Places Four Star Playhouse 3PM Adventure of Robin Hood Presenting Olde World Adventures Bonanza Alfred 4PM Tales of Justice Beverly Hillbillies Hitchcock Crime Scene Beverly Hillbillies 5PM On the Job I Married Joan Mr. & Mrs. North The Boys I Married Joan Mr. & Mrs. North 6PM Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet Mickey Rooney Sir Lancelot Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet Welcome to Comedyville Sir Lancelot Still in its early stages, Channel Pittsburgh is a non-profit streaming television station to provide opportunities for local media artists and media students. The programming is to be a mix of local production, classic movies, vintage television shows and more. CUSTOM MADE A custom made program is an CUSTOMIZED A customized program is original series created from comprised of public domain public domain and/or orphan material exclusively episodes of television series that have been for Channel Pittsburgh. modified exclusively for Channel Pittsburgh. SUNDAY appear together for the first this two-part story about an 12:00 a.m. Fright Flick NOVEMBER 1 time in this lush adaptation of immigrant janitor who dis- "The House on Alfred Mason’s historical covers in a local book store Haunted Hill" (1959). -

RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 2800-3399

RCA Discography Part 10 - By David Edwards, Mike Callahan, and Patrice Eyries. © 2018 by Mike Callahan RCA Victor 12 Inch Popular Series LPM/LSP 2800-3399 LPM/LSP 2800 – Country Piano-City Strings – Floyd Cramer [1964] Heartless Heart/Bonaparte's Retreat/Streets Of Laredo/It Makes No Difference Now/Chattanoogie Shoe Shine Boy/You Don't Know Me/Making Believe/I Love You Because/Night Train To Memphis/I Can't Stop Loving You/Cotton Fields/Lonesome Whistle LPM/LSP 2801 – Irish Songs Country Style – Hank Locklin [1964] The Old Bog Road/Too-Ra-Loo-Ra- Loo-Ral (That's An Irish Lullaby)/Danny Dear/If We Only Had Ireland Over Here/I'll Take You Home Again Kathleen/My Wild Irish Rose/Danny Boy/When Irish Eyes Are Smiling/A Little Bit Of Heaven/Galway Bay/Kevin Barry/Forty Shades Of Green LPM 2802 LPM 2803 LPM/LSP 2804 - Encore – John Gary [1964] Tender Is The Night/Anywhere I Wander/Melodie D'amour (Melody Of Love)/And This Is My Beloved/Ol' Man River/Stella By Starlight/Take Me In Your Arms/Far Away Places/A Beautiful Thing/If/(It's Been) Grand Knowing You/Stranger In Paradise LPM/LSP 2805 – On the Country-Side – Norman Luboff Choir [1964] Detroit City/Jambalaya (On The Bayou)/I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry/Your Cheatin’ Heart/You’re The Only Star (In My Blue Heaven)/Tennessee Waltz/I Can’t Stop Loving You/It Makes No Difference Now/Words/Four Walls/Anytime/You Are My Sunshine LPM/LSP 2806 – Dick Schory on Tour – Dick Schory [1964] Baby Elephant Walk/William Told/The Wanderin’ Fifer/Charade/Sing, Sing, Sing/St. -

Actress, Comedian, Author, Humanitarian and Television Icon Betty White to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award at the 42Nd Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards

ACTRESS, COMEDIAN, AUTHOR, HUMANITARIAN AND TELEVISION ICON BETTY WHITE TO RECEIVE LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD AT THE 42ND ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS To be Honored During the Live Television Broadcast Airing Exclusively on Pop Sunday, April 26 at 8:00 p.m. EDT/5:00 p.m. PDT New York, NY – March 16, 2015 - The National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) today announced that television icon, Betty White, will be honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award at the 42nd Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards broadcast on Sunday, April 26, 2015. The awards ceremony will televised live on Pop at 8:00 p.m. EDT/5:00 p.m. PDT from the Warner Bros. Studios in Burbank, CA. “Betty White is an American institution,” said Bob Mauro, President, NATAS. “Betty’s career as a female pioneer has followed television from literally the beginning of the medium, winning her first Emmy Award in 1952, to the digital- streaming future, winning again in 2010. She is one of the most beloved female performers in the history of television and the National Academy is proud to be honoring her with a most well-deserved Lifetime Achievement Award.” “Betty White is the ‘First Lady of Game Shows,’” said Senior Vice President, Daytime, David Michaels. “Betty was the darling of ‘Password, where she met the love of her life, Allen Ludden, and a favorite on ‘Match Game,’ ‘The $25,000 Pyramid,’and countless others. She was the first woman to receive an Emmy Award for Outstanding Game Show Host in 1983 for the show, ‘Just Men.’ From her iconic dramatic turn as Ann Douglas on ‘The Bold and the Beautiful,’ to her classic sitcom performances, to her movies and books, Betty is a woman who has excelled in everything she has ever done. -

The Alpha and the Omega

Sketch Volume 40, Number 2 1975 Article 6 The Alpha and the Omega Chuck Voss∗ ∗Iowa State University Copyright c 1975 by the authors. Sketch is produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press (bepress). http://lib.dr.iastate.edu/sketch The Alpha and the Omega by Chuck Voss Math, Senior NOTH ING shows on the television screen but a large and colorful stage curtain. A mild trumpet fanfare is heard and a voice announces, "Ladies and gentlemen, Orson Bean!" The curtain parts and out leaps a middle-aged man with a tidy beard, a white silk in his jacket's breast pocket, and a bow tie over his fancy turtleneck sweater. As soon as I see him I wonder, "What about Garry Moore, the regular host, the man who resurrected the bow tie, the man who by sheer personal persistence made the bow tie acceptable to the masses, the man without whose efforts Orson Bean could not possibly be standing there on national television wearing a bow tie?" As if to answer my question, Orson Bean begins to talk. "Ladies and gentlebeans, Garry Moore is unable to host the show tonight. It seems he is suffering from an acute identity crisis. He received a letter yesterday from a woman in Kansas troubled by the number of o's in Garry's last name. She asked how it could be that if the number of o's in his last name was less, then it would be more. Garry brooded over this mystical paradox all morning. Finally, letter in hand, he took a stroll through the garden and ended up at the post office where he forgave the befuddled postmaster for allowing such a letter to be delivered. -

American Pop Culture Quiz

Hey, friends! We are so sorry that we can’t present a “When Swing Was King” show for you this month but the “Great Hunkering Down” of Spring 2020 has us all in its grip. And that’s okay. Because of the dangers represented by the Wuhan coronavirus, it makes perfect sense to do what we can to deal with it. Nevertheless, in addition to our fervent and frequent prayers for your safety and health, we also wanted to do something that might relieve a little of the boredom that the quarantines create. We thought, therefore, that a few quizzes and trivia might be of some interest to you. If you like them, we will go ahead and send over to you similar “activity items” every few days. May God pour out His mercies on you, on our caregivers and health officials, our political leaders, and on all those already dealing with not only the coronavirus but all other health issues. Blessings, Denny & Claire Hartford American Pop Culture Quiz 1) Who created Desilu Productions? a) Elvis Presley and Arthur Miller b) Richard Nixon and Elizabeth Taylor c) Lucille Ball and Dezi Arnaz d) Frank Sinatra and John Wayne 2) The character Tonto is from which television show? a) Dragnet b) Hopalong Cassidy c) The Lone Ranger d) Lassie 3) This 1953 show has three ghosts, one of which can be described as a real booze-hound. a) Topper b) The Outer Limits c) Love That Bob d) Dark Shadows 4) Which television show is the phrase "Get out of Dodge" from? a) The Jackie Gleason Show b) Gunsmoke c) Dinah Shore Show d) Leave it to Beaver 5) This children's program had a carrot stealing rabbit and a sleeping/talking clock. -

Adam C. Nedeff¶S Game Show Collection 5,358 Episodes Strong As of 3/23/2010

Adam C. Nedeff¶s Game Show Collection 5,358 Episodes Strong as of 3/23/2010 I: Game Shows II: Game Show Specials III: Unsold Game Show Pilots IV: My Game Show Box Games I: Game Shows ABOUT FACES {1 episode} Tom Kennedy¶s big break as announcer/substitute host. -Episode with Tom Kennedy filling in for Ben Alexander (End segment missing) [AF-1.1/KIN] ALL-STAR BLITZ {2 episodes} You might as well call it ³Hollywood Square of Fortune.´ -Sherlyn Walters, Ted Shackleford, Betty White, Robert Woods (Dark picture but watchable) [ASB- 1.1/OB] -Madge Sinclair, Christopher Hewitt, Abby Dalton, Peter Scolari [ASB-1.2/OB] ALL-STAR SECRETS {3 episodes} Overly-chatty celebrity guessing game. -Conrad Bain, Robert Gulliame, Robert Pine, Dodie Goodman, Ann Lockhart [AlStS-1.1/OC] -David Landsberg, Eva Gabor, Arnold Schwarzenegger(!), Barbara Feldon, David Huddleston (First two minutes missing) [AlStS-1.2/OC] -Bill Cullen, Nanette Fabray, John Schuck, Della Reese, Arte Johnson [AlStS-1.3/OC] BABY GAME {1 episode} Question: On Match Game, you had to make a match to win. On Dating Game, you had to make a date to win. How did you win on a show called Baby Game? -George & Carolyn vs. Gloria & Lloyd [BG-1.1/KIN] BANK ON THE STARS {2 episodes} A pretty nifty memory test with the master emcee. -Johnny Dark, Mr. Hulot¶s Holiday, The Caine Mutiny; Roger Price appears to plug ³Droodles´ [BOTS- 1.1/KIN] -The Long Wait, Knock on Wood, Johnny Dark [BOTS-1.2/KIN] BATTLESTARS {6 episodes} Alex Trebek just isn¶t right for a ³Hollywood Squares´-type show. -

Betty Bio 7-19-12

BETTY WHITE Although she turned 90 in January, 2012, it won’t slow down comedy legend Betty White, one of the funniest and busiest actresses in Hollywood. With a career that has spanned more than 60 years, the seven-time Emmy Award winner has created unforgettable roles in television and film, authored seven books and won numerous awards, including those for her lifelong work for animal welfare. White’s first comedy series, “Life with Elizabeth,” brought her first Emmy Award in 1952, followed by a daily NBC talk/variety show called “The Betty White Show.” She was a recurring regular with over 70 appearances on “The Tonight Show with Jack Paar,” and appeared on “The Merv Griffin Show” and “The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson.” She also subbed as host on all three talk shows. White was a regular with Vicki Lawrence on “Mama’s Family,” as sister Ellen, a role she created with the rest of the company on “The Carol Burnett Show.” Her recurring role as “Happy Homemaker” Sue Ann Nivens in the classic series “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” brought two Emmys for Best Supporting Actress in 1974-75 and 1975-76. She received her fourth Emmy for Best Daytime Game Show Host for “Just Men.” Nominated seven times for Best Actress in a Comedy Series for her role as Rose Nylund in “The Golden Girls,” White won the Emmy the first season in 1985, and later appeared in the spin-off “The Golden Palace” for one season. She earned her next Emmy Award as Best Guest Actress in a Comedy Series on “The John Larroquette Show.” White was nominated for an Emmy in 2011 for her portrayal of “Elka,” the snarky but lovable caretaker on the TV Land series “Hot in Cleveland,” in which she stars alongside Valerie Bertinelli, Jane Leeves and Wendie Malick. -

16 SAG Press Kit 122809

Present A TNT and TBS Special Simulcast Saturday, Jan. 23, 2010 Premiere Times 8 p.m. ET/PT 7 p.m. Central 6 p.m. Mountain (Replay on TNT at 11 pm ET/PT, 10 pm Central, 9 pm Mountain) Satellite and HD viewers should check their local listings for times. TV Rating: TV-PG CONTACTS: Eileen Quast TNT/TBS Los Angeles 310-788-6797 [email protected] Susan Ievoli TNT/TBS New York 212-275-8016 [email protected] Heather Sautter TNT/TBS Atlanta 404-885-0746 [email protected] Rosalind Jarrett Screen Actors Guild Awards® 310-235-1030 [email protected] WEBSITES: http://www.sagawards.org tnt.tv tbs.com America Online Keyword: SAG Awards Table of Contents 16th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards® to be Simulcast Live on TNT and TBS ..........................2 Nominations Announcement .................................................................................................................4 Nominations ............................................................................................................................................5 The Actor® Statuette and the Voting Process ....................................................................................23 Screen Actors Guild Awards Nomenclature .......................................................................................23 Betty White to be Honored with SAG’s 46th Life Achievement Award..............................................24 Q & A with Betty White.........................................................................................................................27 -

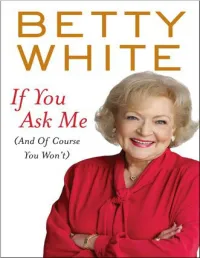

If You Ask Me: (And of Course You Won’T)/Betty White

Table of Contents Title Page Copyright Page Dedication Foreword BODY AND MIND HOLLYWOOD STORIES LETTERS STAGECRAFT LOVE AND FRIENDSHIP ANIMAL KINGDOM STATE OF AFFAIRS SINCE YOU ASKED . Afterword G. P. PUTNAM’S SONS Publishers Since 1838 Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA • Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) • Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Copyright © 2011 by Betty White Photo research by Laura Wyss, Wyssphoto, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions. Published simultaneously in Canada Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data White, Betty, date. If you ask me: (and of course you won’t)/Betty White. p.