SLAMMING the DOOR on DISSENT Wang Dan===S Trial and the New Aaastate Security@@@ Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

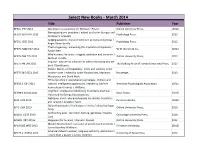

Select New Books - March 2014 Title Publisher Year BF321 .P67 2012 Attention in a Social World / Michael I

Select New Books - March 2014 Title Publisher Year BF321 .P67 2012 Attention in a social world / Michael I. Posner. Oxford University Press, c2012. Stereotyping and prejudice / edited by Charles Stangor and BF323.S63 S747 2013 Psychology Press, 2013. Christian S. Crandall. Judging passions : moral emotions in persons and groups / BF531 .G56 2012 Psychology Press, 2012. Roger Giner-Sorolla. That's disgusting : unraveling the mysteries of repulsion / BF575.A886 H47 2012 W.W. Norton & Co., c2012. Rachel Herz. Why humans like to cry : tragedy, evolution and the brain / BF575.C88 T75 2012 Oxford University Press, 2012. Michael Trimble. Impulse : why we do what we do without knowing why we BF575.I46 L49 2013 The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013. do it / David Lewis. Shame, blame, and culpability : crime and violence in the BF575.S45 S522 2013 modern state / edited by Judith Rowbotham, Marianna Routledge, 2013. Muravyeva, and David Nash. Ethical practice in operational psychology : military and BF636.3 .E84 2011 national intelligence applications / edited by Carrie H. American Psychological Association, c2011. Kennedy and Thomas J. Williams. Ungifted : intelligence redefined / Scott Barry Kaufman ; BF698.9.I6 K38 2013 Basic Books, [2013] illustrated by George Doutsiopoulos. Righteous mind : why good people are divided by politics BJ45 .H25 2012 Pantheon Books, c2012. and religion / Jonathan Haidt. Oxford handbook of the history of ethics / edited by Roger BJ71 .O94 2013 Oxford University Press, 2013. Crisp. Confronting evils : terrorism, torture, genocide / Claudia BJ1401 .C293 2010 Cambridge University Press, 2010. Card. BJ1481 .R87 2012x Happiness for humans / Daniel C. Russell. Oxford University Press, 2012. Muslim Brotherhood : evolution of an Islamist movement / BP10.I385 W53 2013 Princeton University, [2013] Carrie Rosefsky Wickham. -

Chen Xitong Report on Putting Down Anti

Recent Publications The June Turbulence in Beijing How Chinese View the Riot in Beijing Fourth Plenary Session of the CPC Central Committee Report on Down Anti-Government Riot Retrospective After the Storm VOA Disgraces Itself Report on Checking the Turmoil and Quelling the Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion June 30, 1989 Chen Xitong, State Councillor and Mayor of Beijing New Star Publishers Beijing 1989 Report on Checking the Turmoil and Quelling the Counter-Revolutionary Rebellion From June 29 to July 7 the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress - the standing organization of the highest organ of state power in the People's Republic of China - held the eighth meeting of the Seventh National People's Congress in Beijing. One of the topics for discussing at the meeting was a report on checking the turmoil and quelling the counter-revolutionary rebellion in Beijirig. The report by state councillor and mayor of Beijing Chen Xitong explained in detail the process by which a small group of people made use of the student unrest in Beijing and turned it into a counter-revolutionary rebellion by mid-June. It gave a detailed account of the nature of the riot, its severe conse- quence and the efforts made by troops enforcing _martial law, with the help of Beijing residents to quell the riot. The report exposed the behind-the-scene activities of people who stub- bornly persisted in opposing the Chinese Communist Party and socialism as well as the small handful of organizers and schemers of the riot; their collaboration with antagonistic forces at home and abroad; and the atrocities committed by former criminals in beating, looting, burning and First Edition 1989 killing in the riot. -

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989

Confession, Redemption, and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the Protest Movement of 1989 Geremie Barmé1 There should be room for my extremism; I certainly don’t demand of others that they be like me... I’m pessimistic about mankind in general, but my pessimism does not allow for escape. Even though I might be faced with nothing but a series of tragedies, I will still struggle, still show my opposition. This is why I like Nietzsche and dislike Schopenhauer. Liu Xiaobo, November 19882 I FROM 1988 to early 1989, it was a common sentiment in Beijing that China was in crisis. Economic reform was faltering due to the lack of a coherent program of change or a unified approach to reforms among Chinese leaders and ambitious plans to free prices resulted in widespread panic over inflation; the question of political succession to Deng Xiaoping had taken alarming precedence once more as it became clear that Zhao Ziyang was under attack; nepotism was rife within the Party and corporate economy; egregious corruption and inflation added to dissatisfaction with educational policies and the feeling of hopelessness among intellectuals and university students who had profited little from the reforms; and the general state of cultural malaise and social ills combined to create a sense of impending doom. On top of this, the government seemed unwilling or incapable of attempting to find any new solutions to these problems. It enlisted once more the aid of propaganda, empty slogans, and rhetoric to stave off the mounting crisis. University students in Beijing appeared to be particularly heavy casualties of the general malaise. -

Standoff at Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: the Making of Goddess of Democracy

2019/4/23 Standoff At Tiananmen: Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy 更多 创建博客 登录 Standoff At Tiananmen How Chinese Students Shocked the World with a Magnificent Movement for Democracy and Liberty that Ended in the Tragic Tiananmen Massacre in 1989. Relive the history with this blog and my book, "Standoff at Tiananmen", a narrative history of the movement. Home Days People Documents Pictures Books Recollections Memorials Monday, May 30, 2011 "Standoff at Tiananmen" English Language Edition Recollections of 1989: The Making of Goddess of Democracy Click on the image to buy at Amazon "Standoff at Tiananmen" Chinese Language Edition On May 30, 1989, the statue Goddess of Democracy was erected at Tiananmen Square and became one of the lasting symbols of the 1989 student movement. The following is a re-telling of the making of that statue, originally published in the book Children of Dragon, by a sculptor named Cao Xinyuan: Nothing excites a sculptor as much as seeing a work of her own creation take shape. But although I was watching the creation of a sculpture that I had had no part in making, I nevertheless felt the same excitement. It was the "Goddess of Democracy" statue that stood for five days in Tiananmen Square. Until last year I was a graduate student at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, where the sculpture was made. I was living there when these events took place. 点击图像去Amazon购买 Students and faculty of the Central Academy of Fine Arts, which is located only a short distance from Tiananmen Square, had from the beginning been actively involved in the demonstrations. -

Resource List

Resource List rative activities relating to June 4th. The Nomination of the Tiananmen Mothers for Web site contains information about ongo- the Nobel Peace Prize 2004 The 1989 ing and upcoming campaigns and rallies in http://209.120.234.77/64/press/ .2, Democracy Movement Hong Kong and overseas. It also provides TiananmenMothersPackage_2004_Final.pdf NO links to many other relevant Web sites. English COMPILED BY STACY MOSHER This packet of materials was prepared by Independent Federation of Chinese Stu- the Independent Federation of Chinese Stu- dents and Scholars dents and Scholars to support their nomi- WEB SITES: www.ifcss.net nation of the Tiananmen Mothers for the FORUM Chinese and English 2004 Nobel Peace Prize. 64 Memo The IFCSS was founded in Chicago in Princeton Professor Perry Link’s letter of http://www.64memo.org/index.asp August 1989 by more than 1,000 Chinese nomination can be read in Chinese at: RIGHTS Chinese student representatives from more than http://www.dajiyuan.com/gb/4/4/2/n499 Operated by Tiananmen veteran Feng 200 U.S. universities, and remains the 469.htm CHINA Congde and sponsored by HRIC, this Web most influential overseas Chinese student The text was transcribed from Link’s site provides an archive of documents, arti- group. Although less active in recent years, broadcast of the letter on Radio Free Asia. 79 cles and images relating to June 4th. IFCSS is organizing the collection of arti- cles, documents and photos relating to its Tiananmen Square, 1989: The Declassi- Boxun.com Tiananmen Feature upcoming 15th anniversary. fied History http://www.boxun.com/my-cgi/post/ http://www.gwu.edu/~nsarchiv/NSAEBB/N TURES display_all.cgi?cat=64 June 4th Essays SAEBB16/ FEA Chinese http://www.dajiyuan.com/gb/nf2976.htm English Boxun’s special section of photos, articles Chinese An archive of official documents of the U.S. -

Wikileaks Advisory Council

1 WikiLeaks Advisory Council 2 Hi everyone, My name is Tom Dalo and I am currently a senior at Fairfield. I am very excited to Be chairing the WikiLeaks Advisory Council committee this year. I would like to first introduce myself and tell you a little Bit about myself. I am from Allendale, NJ and I am currently majoring in Accounting and Finance. First off, I have been involved with the Fairfield University Model United Nations Team since my freshman year when I was a co-chair on the Disarmament and International Security committee. My sophomore year, I had the privilege of Being Co- Secretary General for FUMUN and although it was a very time consuming event, it was truly one of the most rewarding experiences I have had at Fairfield. Last year I was the Co-Chair for the Fukushima National Disaster Committee along with Alli Scheetz, who filled in as chair for the committee as I was unaBle to attend the conference. Aside from my chairing this committee, I am currently FUMUN’s Vice- President. In addition to my involvement in the Model UN, I am a Tour Ambassador Manager, and a Beta Alpha Psi member. I love the outdoors and enjoy skiing, running, and golfing. I am from Allendale, NJ and I am currently majoring in Accounting and Finance. Some of you may wonder how I got involved with the Model United Nations considering that I am a business student majoring in Accounting and Finance. Model UN offers any student, regardless of their major, a chance to improve their puBlic speaking, enhance their critical thinking skills, communicate Better to others as well as gain exposure to current events. -

China's Fear of Contagion

China’s Fear of Contagion China’s Fear of M.E. Sarotte Contagion Tiananmen Square and the Power of the European Example For the leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), erasing the memory of the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen Square massacre remains a full-time job. The party aggressively monitors and restricts media and internet commentary about the event. As Sinologist Jean-Philippe Béja has put it, during the last two decades it has not been possible “even so much as to mention the conjoined Chinese characters for 6 and 4” in web searches, so dissident postings refer instead to the imagi- nary date of May 35.1 Party censors make it “inconceivable for scholars to ac- cess Chinese archival sources” on Tiananmen, according to historian Chen Jian, and do not permit schoolchildren to study the topic; 1989 remains a “‘for- bidden zone’ in the press, scholarship, and classroom teaching.”2 The party still detains some of those who took part in the protest and does not allow oth- ers to leave the country.3 And every June 4, the CCP seeks to prevent any form of remembrance with detentions and a show of force by the pervasive Chinese security apparatus. The result, according to expert Perry Link, is that in to- M.E. Sarotte, the author of 1989: The Struggle to Create Post–Cold War Europe, is Professor of History and of International Relations at the University of Southern California. The author wishes to thank Harvard University’s Center for European Studies, the Humboldt Foundation, the Institute for Advanced Study, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and the University of Southern California for ªnancial and institutional support; Joseph Torigian for invaluable criticism, research assistance, and Chinese translation; Qian Qichen for a conversation on PRC-U.S. -

CONFRONTING ATROCITIES in CHINA: the Global Response to the Uyghur Crisis

June 6-7, 2019 CONFRONTING Washington, DC ATROCITIES Opening Ceremony: U.S. Capitol Building IN CHINA: Conference: George Washington University THE GLOBAL RESPONSE TO THE UYGHUR CRISIS The World Uyghur Congress in cooperation with the Uyghur Human Rights Project (UHRP), Uyghur American Association (UAA) and the Central Asia Program (CAP) at George Washington University present: CONFRONTING ATROCITIES IN CHINA: The Global Response to the Uyghur Crisis (Eventbrite Registration required) Opening Ceremony: June 6, 9:00-12:30 U.S. Capitol Visitor Center, Room HVC-201 Conference: June 6, 14:00-18:00 & June 7, 9:30-18:00 Elliott School of International Affairs, 1957 E St NW (State Room) Confronting Atrocities in China: The Global Response to the Uyghur Crisis Conference Background: The Uyghur population has faced human rights abuses at the hands of the Chinese government for many years, but since 2017, China has operated an extensive netWork of internment camps stretching across East Turkistan (the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China) that funCtion to soCially re-engineer the Uyghur population and erode the most basiC elements of the Uyghur identity. The Camps exist as the logical conClusion of deCades of Chinese policy designed to undermine Uyghur identity and expression. Thus far, despite extensive Coverage and reporting on Conditions in the region, the international community has been tremendously cautious in their approach With China on the issue. Although some states and international organizations have spoken out strongly on the abuses, little by Way of ConCrete action has been achieved WhiCh Would forCe China to Change Course. The ConferenCe inCludes speakers from various backgrounds and disCiplines to disCuss and address a number of key open questions on hoW best to galvanize further support for Uyghurs, to mount a coordinated campaign to pressure China to close the camps, ensure accountability for those responsible for ongoing abuses, and adopt measures to safeguard fundamental rights. -

Inventory of the Collection Chinese People's Movement, Spring 1989 Volume Ii: Audiovisual Materials, Objects and Newspapers

International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ INVENTORY OF THE COLLECTION CHINESE PEOPLE'S MOVEMENT, SPRING 1989 VOLUME II: AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS, OBJECTS AND NEWSPAPERS at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ For a list of the Working Papers published by Stichting beheer IISG, see page 181. International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ Frank N. Pieke and Fons Lamboo INVENTORY OF THE COLLECTION CHINESE PEOPLE'S MOVEMENT, SPRING 1989 VOLUME II: AUDIOVISUAL MATERIALS, OBJECTS AND NEWSPAPERS at the International Institute of Social History (IISH) Stichting Beheer IISG Amsterdam 1991 International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ CIP-GEGEVENS KONINLIJKE BIBLIOTHEEK, DEN HAAG Pieke, Frank N. Inventory of the Collection Chinese People's Movement, spring 1989 / Frank N. Pieke and Fons Lamboo. - Amsterdam: Stichting beheer IISG Vol. II: Audiovisual Materials, Objects and Newspapers at the International Institute of Social History (IISH). - (IISG-werkuitgaven = IISG-working papers, ISSN 0921-4585 ; 16) Met reg. ISBN 90-6861-060-0 Trefw.: Chinese volksbeweging (collectie) ; IISG ; catalogi. c 1991 Stichting beheer IISG All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar worden gemaakt door middel van druk, fotocopie, microfilm of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. Printed in the Netherlands International Institute of Social History www.iisg.nl/collections/tiananmen/ TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents v Preface vi 1. -

Tiananmen Square

The Tiananmen Legacy Ongoing Persecution and Censorship Ongoing Persecution of Those Seeking Reassessment .................................................. 1 Tiananmen’s Survivors: Exiled, Marginalized and Harassed .......................................... 3 Censoring History ........................................................................................................ 5 Human Rights Watch Recommendations ...................................................................... 6 To the Chinese Government: .................................................................................. 6 To the International Community ............................................................................. 7 Ongoing Persecution of Those Seeking Reassessment The Chinese government continues to persecute those who seek a public reassessment of the bloody crackdown. Chinese citizens who challenge the official version of what happened in June 1989 are subject to swift reprisals from security forces. These include relatives of victims who demand redress and eyewitnesses to the massacre and its aftermath whose testimonies contradict the official version of events. Even those who merely seek to honor the memory of the late Zhao Ziyang, the secretary general of the Communist Party of China in 1989 who was sacked and placed under house arrest for opposing violence against the demonstrators, find themselves subject to reprisals. Some of those still targeted include: Ding Zilin and the Tiananmen Mothers: Ding is a retired philosophy professor at -

1989 Tiananmen Square: a Proto-History

1989 Tiananmen Square: A Proto-History Karman Miguel Lucero April 4th, 2011 Thesis Seminar Professor: Mae M. Ngai Second Reader: Dorothy Ko Word Count: 19,883 1 Acknowledgements This project would not have been possible without the advice, wisdom, and assistance of several individuals. I would like to thank my fellow students at Tsinghua University for providing me with source materials and assisting me in developing my own historical consciousness. Furthermore, I would like to thank Professors Tang Shaojie and Hu Weixi, not for their direct involvement with this project, but for their inspiring commitment to academic integrity and dedication to the wonderful possibilities that can result from receiving a good education. I owe much gratitude to Columbia Professor Lydia Liu, who not only offered her invaluable advice, but also provided me access to sources that are a critical component of this paper. Thank you to Ouyang Jianghe for his time and wisdom as well as to Qin Wuming (pseudonym), for letting me read his deeply moving essay. A special thank you goes to Mae M. Ngai, my senior thesis seminar professor, who has helped me throughout this process and shared in the excitement. Thank you to Dorothy Ko and Lisa J. Lucero for their priceless feedback and to Madeleine Zelin and Andrew Nathan for their advice. The passion and integrity of my various history teachers and professors have inspired me and contributed a great deal to my appreciation of history. Thank you in particular to Liu Lu, Volker R. Berghahn, and Gray Tuttle at Columbia University , each of whom really inspired my appreciation for the craft of history. -

The Political Repression of Chinese Students After Tiananmen A

University of Nevada, Reno “To yield would mean our end”: The Political Repression of Chinese Students after Tiananmen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by Katherine S. Robinson Dr. Hugh Shapiro/Thesis Advisor May, 2011 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by KATHERINE S. ROBINSON entitled “To Yield Would Mean Our End”: The Political Repression Of Chinese Students After Tiananmen be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Hugh Shapiro, Ph.D, Advisor Barbara Walker, Ph.D., Committee Member Jiangnan Zhu, Ph.D, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Associate Dean, Graduate School May, 2011 i ABSTRACT Following the military suppression of the Democracy Movement, the Chinese government enacted politically repressive policies against Chinese students both within China and overseas. After the suppression of the Democracy Movement, officials in the Chinese government made a correlation between the political control of students and the maintenance of political power by the Chinese Communist Party. The political repression of students in China resulted in new educational policies that changed the way that universities functioned and the way that students were allowed to interact. Political repression efforts directed at the large population of overseas Chinese students in the United States prompted governmental action to extend legal protection to these students. The long term implications of this repression are evident in the changed student culture among Chinese students and the extensive number of overseas students who did not return to China.