Larson, Jonathan (1960-1996)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

YMTC to Present the Rock Musical Rent, November 3–10 in El Cerrito

Youth Musical Theater Company FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Inquiries: Laura Soble/YMTC Phone 510-595-5514 Email: [email protected] Website: https://www.ymtcbayarea.org YMTC to Present the Rock Musical Rent, November 3–10 in El Cerrito Berkeley, California, September 27, 2019—Youth Musical Theater Company (YMTC) will launch its 15th season of acclaimed regional theater with the rock musical Rent. The show opens Sunday, November 3, at the Performing Arts Theater, 540 Ashbury Ave., El Cerrito. Its run consists of a 5:00 p.m. opening (11/3), two 2:00 p.m. matinees (11/9, 11/10), and three 7:30 p.m. performances (11/7, 11/8, 11/9). Rent is a rock opera loosely based on Puccini’s La Boheme, with music, lyrics, and book by Jonathan Larson. Set in Lower Manhattan’s East Village during the turmoil of the AIDS crisis, this moving story chronicles the lives of a group of struggling artists over a year’s time. Its major themes are community, friendship, and survival. In 1996, Rent received four Tony Awards, including Best Musical; six Drama Desk Awards; and the Pulitzer Prize for Drama. In 1997, it won the Grammy Award for Best Musical Show Album. Its Broadway run lasted 12 years. Co-Director Jennifer Boesing comments, “Rent is a love story and a bold, brazen manifesto for young artists who are trying not just to stay alive, but to stay connected to each other, when the mainstream culture seems to be ignoring signs of destruction all around them. Although the show today is a period piece about a very specific historical moment—well before the earliest memories of our young performing artists—they relate to it deeply just the same. -

Dstprogram-Ticktickboom

SCOTTSDALE DESERT STAGES THEATRE PRESENTS May 7 – 16, 2021 DESERT STAGES THEATRE SCOTTSDALE, ARIZONA PRESENTS TICK, TICK...BOOM! Book, Music and Lyrics by Jonathan Larson David Auburn, Script Consultant Vocal Arrangements and Orchestrations by Stephen Oremus TICK, TICK...BOOM! was originally produced off-Broadway in June, 2001 by Victoria Leacock, Robyn Goodman, Dede Harris, Lorie Cowen Levy, Beth Smith Co-Directed by Mark and Lynzee 4man TICK TICK BOOM! is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. www.mtishows.com WELCOME TO DST Welcome to Desert Stages Theatre, and thank you for joining us at this performance of Jonathan Larson’s TICK, TICK...BOOM! The talented casts that will perform in this show over the next two weekends include some DST “regulars” - familiar faces that you have seen here before - as well as actors who are brand new to the DST stage. Thank you to co- directors Mark and Lynzee 4man who were the natural choices to co- direct (and music direct and choreograph) a rock musical that represents our first teen/young adult production in more than a year. They have worked tirelessly with an extremely skilled team of actors, designers, and crew members to bring you this beautiful show, and everyone involved has enjoyed the process very much. We continue our COVID-19 safety protocols and enhanced cleaning measures to keep you and our actors safe. In return, we ask that you kindly wear your mask the entire time you are in the theatre, and stay in your assigned seat. -

Jonathan Larson

Famous New Yorker Jonathan Larson As a playwright, Jonathan Larson could not have written a more dramatic climax than the real, tragic climax of his own story, one of the greatest success stories in modern American theater history. Larson was born in White Plains, Westchester County, on February 4, 1960. He sang in his school choir, played tuba in the band, and was a lead actor in his high school theater company. With a scholarship to Adelphi University, he learned musical composition. After earning a Fine Arts degree, Larson had to wait tables, like many a struggling artist, to pay his share of the rent in a poor New York City apartment while honing his craft. In the 1980s and 1990s, Larson worked in nearly every entertainment medium possible. He won early recognition for co-writing the award-winning cabaret show Saved!, but his rock opera Superbia, inspired by The original Broadway Rent poster George Orwell’s novel 1984, was never fully staged in Larson’s lifetime. Scaling down his ambitions, he performed a one-man show called tick, tick … BOOM! in small “Off -Broadway” theaters. In between major projects, Larson composed music for children’s TV shows, videotapes and storybook cassette tapes. In 1989, playwright Billy Aronson invited Larson to compose the music for a rock opera inspired by La Bohème, a classical opera about hard-living struggling artists in 19th century Paris. Aronson wanted to tell a similar story in modern New York City. His idea literally struck Larson close to home. Drawing on his experiences as a struggling musician, as well as many friends’ struggles with the AIDS virus, Larson wanted to do all the writing himself. -

“Kiss Today Goodbye, and Point Me Toward Tomorrow”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By BRYAN M. VANDEVENDER Dr. Cheryl Black, Dissertation Supervisor July 2014 © Copyright by Bryan M. Vandevender 2014 All Rights Reserved The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled “KISS TODAY GOODBYE, AND POINT ME TOWARD TOMORROW”: REVIVING THE TIME-BOUND MUSICAL, 1968-1975 Presented by Bryan M. Vandevender A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. Cheryl Black Dr. David Crespy Dr. Suzanne Burgoyne Dr. Judith Sebesta ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I incurred several debts while working to complete my doctoral program and this dissertation. I would like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to several individuals who helped me along the way. In addition to serving as my dissertation advisor, Dr. Cheryl Black has been a selfless mentor to me for five years. I am deeply grateful to have been her student and collaborator. Dr. Judith Sebesta nurtured my interest in musical theatre scholarship in the early days of my doctoral program and continued to encourage my work from far away Texas. Her graduate course in American Musical Theatre History sparked the idea for this project, and our many conversations over the past six years helped it to take shape. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1k1860wx Author Ellis, Sarah Taylor Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies by Sarah Taylor Ellis 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Doing the Time Warp: Queer Temporalities and Musical Theater by Sarah Taylor Ellis Doctor of Philosophy in Theater and Performance Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Sue-Ellen Case, Co-chair Professor Raymond Knapp, Co-chair This dissertation explores queer processes of identification with the genre of musical theater. I examine how song and dance – sites of aesthetic difference within the musical – can warp time and enable marginalized and semi-marginalized fans to imagine different ways of being in the world. Musical numbers can complicate a linear, developmental plot by accelerating and decelerating time, foregrounding repetition and circularity, bringing the past to life and projecting into the future, and physicalizing dreams in a narratively open present. These excesses have the potential to contest naturalized constructions of historical, progressive time, as well as concordant constructions of gender, sexual, and racial identities. While the musical has historically been a rich source of identification for the stereotypical white gay male show queen, this project validates a broad and flexible range of non-normative readings. -

Hair for Rent: How the Idioms of Rock 'N' Roll Are Spoken Through the Melodic Language of Two Rock Musicals

HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Eryn Stark August, 2015 HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS Eryn Stark Thesis Approved: Accepted: _____________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Nikola Resanovic Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ...............................................................................3 A History of the Rock Musical: Defining A Generation .........................................3 Hair-brained ...............................................................................................12 IndiffeRent .................................................................................................16 III. EDITORIAL METHOD ..............................................................................................20 -

Sweat, by Lynn Nottage, Was Developed by Co-Commission from the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’S American Revolutions: the United States History Cycle and Arena Stage

Sweat, by Lynn Nottage, was developed by co-commission from the Oregon Shakespeare Festival’s American Revolutions: The United States History Cycle and Arena Stage. The play is centered on the working class of Reading, Pennsylvania. Lynn Nottage began working on the play in 2011 by interviewing numerous residents of Reading, Pennsylvania, which at the time was, according to the United States Census Bureau, officially one of the poorest cities in America, with a poverty rate of over 40%. Nottage has said that she was particularly influenced by a New York Times article reporting on the city specifically, and by the Occupy Wall Street movement more generally. She explored the effects on residents of the loss of heavy industry and the changing ethnic composition of the city. Shifting in time between 2000 and 2008, taking place mostly in the local bar, Sweat tells the story of a group of friends, who have spent their lives sharing drinks, secrets, and laughs while working together on the factory floor. When layoffs and picket lines begin to chip away at their trust, the friends find themselves pitted against each other in a heart-wrenching fight to stay afloat. “…a cautionary tale of what happens when you don’t know how to resist.” – Time Out New York “Nottage feels that what unifies her plays is their “morally ambiguous heroes or heroines, people who are fractured within their own bodies, who have to make very difficult choices in order to survive.”… The plays also give voice to marginalized lives.” – The New Yorker Winner of the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Drama On her research and approach to developing the play while in Reading, Nottage adopted the motto, “Replace judgement with curiosity.” It would be tested. -

American Stage Presents the 2015 Pulitzer Prize Winner, BETWEEN RIVERSIDE & CRAZY

For Immediate Release September 19, 2018 Contact: The American Stage Marketing Team (727) 823-1600 x 209 [email protected] American Stage presents the 2015 Pulitzer Prize winner, BETWEEN RIVERSIDE & CRAZY. A dark urban comedy about a retired police officer fighting to keep his rent-controlled apartment. October 3 thru November 4. GET IN-THE-KNOW ABOUT THE PRODUCTION 1. One of the most celebrated new American plays. Stephen Adly Guirgis' play won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, the 2015 New York Drama Critics Circle Award for Best Play, the 2015 Lucille Lortel Award for Outstanding Play, the 2015 Outer Critics Circle Award for Outstanding New Off-Broadway Play and the 2015 Off Broadway Alliance Award for Best New Play. 2. L. Peter Callender makes his American Stage debut as an actor. As an actor, he has performed coast to coast over the years in over 15 regional theaters and has appeared on Broadway in PRELUDE TO A KISS (Helen Hayes Theater). Mr. Callender has also directed three critically acclaimed and award-winning American Stage productions (JITNEY, JOE TURNER'S COME & GONE and A RAISIN IN THE SUN) and will be returning in January to direct Dominique Morisseau's PIPELINE. 3. Powerfully relevant Tampa Bay premiere by one of America's top playwrights. BETWEEN RIVERSIDE & CRAZY at its core asks us to examine what makes us who we are. Is it our jobs, our families, or our actions? Stephen Adly Guirgis, winner of the Steinberg Distinguished Playwright Award, tackles these complex questions in this play with nuance humor and heart. -

2019 Summer Season Announcement

1 Press Contacts: Katie B. Watts Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] Please embargo until: Thursday, February 14 at 5pm Berkshire Theatre Group Announces 2019 Summer Season The Fitzpatrick Main Stage Pulitzer Prize-Winner Thornton Wilder’s American Classic The Skin of Our Teeth Kathleen Clark’s World Premiere of What We May Be The Unicorn Theatre Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-Winner Edward Albee’s The Goat or, Who is Sylvia? Pulitzer Prize and Tony Award-Winner John Patrick Shanley’s Outside Mullingar Tony Award-Nominated Musical Featuring Music By Lin-Manuel Miranda and James Taylor Working: A Musical Mark Harelik’s Touching Drama What The Jews Believe The Colonial Theatre In Association with Tony Award-Winning Caiola Productions 2 New Musical Rock and Roll Man: The Alan Freed Story Based on Oscar-Winning Film Tony Award-Nominated Shrek The Musical Hershey Felder’s Celebrated Musical Play George Gershwin Alone Delightful Musical Adventure Roald Dahl's Willy Wonka KIDS Pittsfield, MA – Berkshire Theatre Group (BTG) and Kate Maguire (Artistic Director, CEO) are thrilled to announce Berkshire Theatre’s 2019 Summer Season. BTG will be releasing a season cast announcement at a later date. According to Maguire, “Coming in on the heels of last year’s 90th celebration, I found myself looking at how we love and care for each other. Which means our 91st season is eclectic and wide open to all kinds of interpretations because we love in so many different ways.” Maguire continues, “We find love in the strangest and most bizarre places in our first play of the 2019 season at The Unicorn Theatre, The Goat or, Who is Sylvia by one of our greatest playwrights, Edward Albee. -

ENSEMBLE ACTING: Blocking and Character Development STEP 1

ENSEMBLE ACTING: Blocking and Character Development STEP 1: SCRIPT SELECTION 1. Select scripts that portray three-dimensional characters - “Scenes written to be scenes” often have characters that can feel like cardboard - Try editing a scene from a full-length play for well-rounded characterizations - Most importantly, the characters must change and grow throughout the scene 2. Select scenes that have emotional range - Too much tragedy for 15 minutes can feel tedious – give the audience a break - The most successful scenes will infuse a combination of comedy and drama - If you can make the audience laugh and cry in the same scene, you are golden - Every good scene is like a roller coaster – keep the audience on the roller coaster for 15 minutes 3. Find scenes that match the skill set of your potential actors - Get to know your potential speech team members and find their strengths - It is important to give actors opportunities to show range, but you also want to set them up to be successful - 90% of directing is casting SCRIPT RESOURCES Samuel French www.samuelfrench.com BEST Dramatists Play Service www.dramatists.com Playscripts, Inc. www.playscripts.com Dramatic Publishing www.dramaticpublishing.com Brooklyn Publishers www.brookpub.com Pioneer Drama www.pioneerdrama.com DUBUQUE SENIOR ENSEMBLE ACTING SELECTIONS (2004-Present) ‘Night Mother* Marsha Norman Full Length Play Dramatists A Midsummer Night’s Dream* William Shakespeare Full Length Play Public Domain Battle of Bull Run Always Makes Me Cry* Carole Real Scene David Friedlander -

PDF Program Download

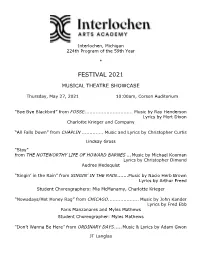

Interlochen, Michigan 224th Program of the 59th Year * FESTIVAL 2021 MUSICAL THEATRE SHOWCASE Thursday, May 27, 2021 10:00am, Corson Auditorium “Bye Bye Blackbird” from FOSSE ............................... Music by Ray Henderson Lyrics by Mort Dixon Charlotte Krieger and Company “All Falls Down” from CHAPLIN .............. Music and Lyrics by Christopher Curtis Lindsay Gross “Stay” from THE NOTEWORTHY LIFE OF HOWARD BARNES ... Music by Michael Kooman Lyrics by Christopher Dimond Audree Hedequist “Singin’ in the Rain” from SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN ....... Music by Nacio Herb Brown Lyrics by Arthur Freed Student Choreographers: Mia McManamy, Charlotte Krieger “Nowadays/Hot Honey Rag” from CHICAGO .................... Music by John Kander Lyrics by Fred Ebb Paris Manzanares and Myles Mathews Student Choreographer: Myles Mathews “Don’t Wanna Be Here” from ORDINARY DAYS ..... Music & Lyrics by Adam Gwon JT Langlas “No One Else” from NATASHA, PIERRE AND THE GREAT COMET OF 1812 ......... Music and Lyrics by Dave Malloy Mia McManamy “Run, Freedom, Run” from URINETOWN ...................... Music by Mark Hollmann Lyrics by Mark Hollmann and Greg Kotis Scout Carter and Company “Forget About the Boy” from THOROUGHLY MODERN MILLIE ........................... Music by Jeanine Tesori Lyrics by Dick Scanlan Hannah Bank and Company Student Choreographer: Nicole Pellegrin “She Used to Be Mine” from WAITRESS ........ Music and Lyrics by Sara Bareilles Caroline Bowers “Change” from A NEW BRAIN ......................... Music and Lyrics by William Finn Shea Grande “We Both Reached for the Gun” from CHICAGO .............. Music by John Kander Lyrics by Fred Ebb Theo Gyra and Company Student Choreographer: Myles Mathews “Love is an Open Door” from FROZEN ............ Music & Lyrics by Kristen Anderson-Lopez & Robert Lopez Charlotte Krieger and Daniel Rosales “Being Alive” from COMPANY ............... -

Review Essay: Lullaby for Broadway?

Review Essay: Lullaby for Broadway? Grant, Mark N. 2004. The Rise and Fall of the Broadway Musical. Boston: Northeastern University Press. Knapp, Raymond. 2005. The American Musical and the Formation of National Identity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Swayne, Steve. 2005. How Sondheim Found His Sound. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Reviewed by Walter Frisch I. Latecomers to high culture, Americans are obsessed with identifying and canonizing indigenous art forms. In recent years, much of this attention has been lavished on jazz. Musical theater is beginning to catch up, to judge from the recent rash of companions, readers, and reference works.! As Stephen Banfield, a dean among scholars of the American musical, observed in a 2004 review essay, "So many academic books and articles have by now lamented 'that the musical has been neglected by academics as an area of study' that it has to be patently untrue" (2004:83).2 One challenge in the study of both jazz and musical theater is locating the specific historical moment or the precise works in which the genres assume an identity, especially an ''American'' one, distinct from their influences. For musical theater, those sources would include European operetta of the later nineteenth century-specifically the works of Johann Strauss, Offenbach, and Gilbert and Sullivan-as well as vaudeville, burlesque, revue, minstrel shows, variety shows, melodrama, and British musical comedy. In the first few years of the twentieth century, these traditions coalesced in the works of Victor Herbert (notably his Babes in Toyland, 1903) and George M. Cohan (his first big hit, Little Johnny Jones, 1904).