In the Nooks and Crannies of Colonial History Repose Records of a Past Thrown Into Deep Shadow by the Brilliancy of Later Events

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

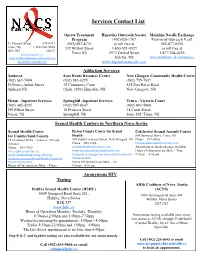

Services Contact List

Services Contact List Opiate Treatment Hepatitis Outreach Society Mainline Needle Exchange Program (902)420-1767 Provincial Outreach # call 33 Pleasant Street, 895-0931 (902) 893-4776 or toll free at 902-877-0555 Truro, NS 1 866-940-AIDS 332 Willow Street 1-800-521-0527 or toll free at B2N 3R5 (2437) [email protected] Truro NS 2973 Oxford Street 1-877-904-4555 www.northernaidsconnectionsociety.ca Halifax, NS www.mainlineneedleexchange.ca facebook.com/nacs.ns www.hepatitisoutreach.com Addiction Services Amherst- East Hants Resource Center New Glasgow Community Health Center (902) 667-7094 (902) 883-0295 (902) 755-7017 30 Prince Arthur Street 15 Commerce Court 835 East River Road Amherst,NS (Suite #250) Elmsdale, NS New Glasgow, NS Pictou - Inpatient Services Springhill -Inpatient Services Truro - Victoria Court (902) 485-4335 (902) 597-8647 (902) 893-5900 199 Elliott Street 10 Princess Street 14 Court Street, Pictou, NS Springhill, NS Suite 205, Truro, NS Sexual Health Centers in Northern Nova Scotia Sexual Health Center Pictou County Center for Sexual Colchester Sexual Assault Center for Cumberland County Health 80 Glenwood Drive, Truro, NS 11 Elmwood Drive , Amherst , NS side 503 South Frederick Street, New Glasgow, NS Phone 897-4366 entrance Phone 695-3366 [email protected] Phone 667-7500 [email protected] No website or facebook page available [email protected] www.pictoucountysexualhealth.com Hours of Operation are Mon. - Thur. www.cumberlandcounty.cfsh.info facebook.com/pages/pictou-county-centre-for- 9:30am – 4:30 pm facebook.com/page/Sexual-Health-Centre-for- Sexual-Health Cumberland-County Hours of Operation are Mon. -

The Siege of Fort Beauséjour by Chris M. Hand Notes

1 The Siege of Fort Beauséjour by Chris M. Hand Notes Early Conflict in Nova Scotia 1604-1749. By the end of the 1600’s the area was decidedly French. 1713 Treaty of Utrecht After nearly 25 years of continuous war, France ceded Acadia to Britain. French and English disagreed over what actually made up Acadia. The British claimed all of Acadia, the current province of New Brunswick and parts of the current state of Maine. The French conceded Nova Scotia proper but refused to concede what is now New Brunswick and northern Maine, as well as modern Prince Edward Island and Cape Breton. They also chose to limit British ownership along the Chignecto Isthmus and also harboured ambitions to win back the peninsula and most of the Acadian settlers who, after 1713, became subjects of the British Crown. The defacto frontier lay along the Chignecto Isthmus which separates the Bay of Fundy from the Northumberland Strait on the north. Without the Isthmus and the river system to the west, France’s greatest colony along the St. Lawrence River would be completely cut off from November to April. Chignecto was the halfway house between Quebec and Louisbourg. 1721 Paul Mascarene, British governor of Nova Scotia, suggested that a small fort could be built on the neck with a garrison of 150 men. a) one atthe ridge of land at the Acadian town of Beaubassin (now Fort Lawrence) or b) one more west on the more prominent Beauséjour ridge. This never happened because British were busy fighting Mi’kmaq who were incited and abetted by the French. -

Where to Go for Help – a Resource Guide for Nova Scotia

WHERE TO GO ? FOR HELP A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR NOVA SCOTIA WHERE TO GO FOR HELP A Resource Guide for Nova Scotia v 3.0 August 2018 EAST COAST PRISON JUSTICE SOCIETY Provincial Divisions Contents are divided into the following sections: Colchester – East Hants – Cape Breton Cumberland Valley – Yarmouth Antigonish – Pictou – Halifax Guysborough South Shore Contents General Phone Lines - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 Crisis Lines - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 HALIFAX Community Supports & Child Care Centres - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 Food Banks / Soup Kitchens / Clothing / Furniture - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 17 Resources For Youth - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 20 Mental, Sexual And Physical Health - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 22 Legal Support - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 28 Housing Information - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 31 Shelters / Places To Stay - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 33 Financial Assistance - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 35 Finding Work - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 36 Education Support - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 39 Supportive People In The Community – Hrm - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 40 Employers who do not require a criminal record check - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 41 COLCHESTER – EAST HANTS – CUMBERLAND Community Supports And Child Care Centres -

The Boundaries of Nationality in Mid-18Th Century Nova Scotia*

GEOFFREY PLANK The Two Majors Cope: The Boundaries of Nationality in Mid-18th Century Nova Scotia* THE 1750S BEGAN OMINOUSLY IN Nova Scotia. In the spring of 1750 a company of French soldiers constructed a fort in a disputed border region on the northern side of the isthmus of Chignecto. The British built a semi-permanent camp only a few hundred yards away. The two armies faced each other nervously, close enough to smell each other's food. In 1754 a similar situation near the Ohio River led to an imperial war. But the empires were not yet ready for war in 1750, and the stand-off at Chignecto lasted five years. i In the early months of the crisis an incident occurred which illustrates many of *' the problems I want to discuss in this essay. On an autumn day in 1750, someone (the identity of this person remains in dispute) approached the British fort waving a white flag. The person wore a powdered wig and the uniform of a French officer. He carried a sword in a sheath by his side. Captain Edward Howe, the commander of the British garrison, responded to the white flag as an invitation to negotiations and went out to greet the man. Then someone, either the man with the flag or a person behind him, shot and killed Captain Howe. According to three near-contemporary accounts of these events, the man in the officer's uniform was not a Frenchman but a Micmac warrior in disguise. He put on the powdered wig and uniform in order to lure Howe out of his fort. -

NS Royal Gazette Part I

Nova Scotia Published by Authority PART 1 VOLUME 220, NO. 4 HALIFAX, NOVA SCOTIA, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 26, 2011 Land Transactions by the Province of Schedule “A” Nova Scotia pursuant to the Ministerial Notice of Parcel Registration under the Land Transaction Regulations (MLTR) for Land Registration Act the period February 13, 2009 to October 14, 2010 TAKE NOTICE that ownership of the property known as Name/Grantor Year Fishery Limited PID 20244828, located at 700 Willow Street, Truro, Type of Transaction Grant Colchester County, Nova Scotia, has been registered Location Hacketts Cove under the Land Registration Act, in whole or in part on Halifax County the basis of adverse possession, in the name of Allen Area 1195 square metres Dexter Symes. Document Number 92763250 recorded February 13, 2009 NOTICE is being provided as directed by the Registrar General of Land Titles in accordance with clause Name/Grantor Mariners Anchorage Residents 10(10)(b) of the Land Registration Administration Association Regulations. For further information, you may contact Type of Transaction Grant the lawyer for the registered owner, noted below. Location Glen Haven, Halifax County Area 192 square metres TO: The Heirs of Ernest MacKenzie or other persons Document Number 96826046 who may have an interest in the above-noted property. recorded September 21, 2010 DATED at Pictou, Pictou County, Nova Scotia, this Name/Grantor Welsford, Barbara 17th day of January, 2011. Type of Transaction Grant Location Oakland, Halifax County Ian H. MacLean Area 174 square metres -

EXPLORER Official Visitors Guide

eFREE 2021 Official Visitors Guide Annapolis Rxploroyal & AreaerFREE Special Edition U BEYO D OQW TITEK A Dialongue of Place & D’iversity Page 2, explorer, 2021 Official Visitors Guide Come in and browse our wonderful assortment of Mens and Ladies apparel. Peruse our wide The unique Fort Anne Heritage Tapestry, designed by Kiyoko Sago, was stitched by over 100 volunteers. selection of local and best sellers books. Fort Anne Tapestry Annapolis Royal Kentville 2 hrs. from Halifax Fort Anne’s Heritage Tapestry How Do I Get To Annapolis Royal? Exit 22 depicts 4 centuries of history in Annapolis Holly and Henry Halifax three million delicate needlepoint Royal Bainton's stitches out of 95 colours of wool. It Tannery measures about 18’ in width and 8’ Outlet 213 St George Street, Annapolis Royal, NS Yarmouth in height and was a labor of love 19025322070 www.baintons.ca over 4 years in the making. It is a Digby work of immense proportions, but Halifax Annapolis Royal is a community Yarmouth with an epic story to relate. NOVA SCOTIA Planning a Visit During COVID-19 ANNAPOLIS ROYAL IS CONVENIENTLY LOCATED Folks are looking forward to Fundy Rose Ferry in Digby 35 Minutes travelling around Nova Scotia and Halifax International Airport 120 Minutes the Maritimes. “Historic, Scenic, Kejimkujik National Park & NHS 45 Minutes Fun” Annapolis Royal makes the Phone: 9025322043, Fax: 9025327443 perfect Staycation destination. Explorer Guide on Facebook is a www.annapolisroyal.com Convenience Plus helpful resource. Despite COVID19, the area is ready to welcome visitors Gasoline & Ice in a safe and friendly environment. -

Placenaming on Cape Breton Island 381 a Different View from The

Placenaming on Cape Breton Island A different view from the sea: placenaming on Cape Breton Island William Davey Cape Breton University Sydney NS Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT : George Story’s paper A view from the sea: Newfoundland place-naming suggests that there are other, complementary methods of collection and analysis than those used by his colleague E. R. Seary. Story examines the wealth of material found in travel accounts and the knowledge of fishers. This paper takes a different view from the sea as it considers the development of Cape Breton placenames using cartographic evidence from several influential historic maps from 1632 to 1878. The paper’s focus is on the shift names that were first given to water and coastal features and later shifted to designate settlements. As the seasonal fishing stations became permanent settlements, these new communities retained the names originally given to water and coastal features, so, for example, Glace Bay names a town and bay. By the 1870s, shift names account for a little more than 80% of the community names recorded on the Cape Breton county maps in the Atlas of the Maritime Provinces . Other patterns of naming also reflect a view from the sea. Landmarks and boundary markers appear on early maps and are consistently repeated, and perimeter naming occurs along the seacoasts, lakes, and rivers. This view from the sea is a distinctive quality of the island’s names. Keywords: Canada, Cape Breton, historical cartography, island toponymy, placenames © 2016 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction George Story’s paper The view from the sea: Newfoundland place-naming “suggests other complementary methods of collection and analysis” (1990, p. -

Methodism Among Nova Scotia's Yankee Planters

Methodism Among Nova Scotia's Yankee Planters Allen B. Robertson Queen's University During the 1770s two revivalist evangelical sects gained a following in Nova Scotia; one, Newlight Congregationalism — with both Predestinar- ian and Free Will variants — grew out of the religious and social heritage of the colony's dominant populace, the New England Planters. The other sect, Wesleyan Methodism, took root among transplanted Yorkshiremen who moved between 1772 and 1776 to the Isthmus of Chignecto region where it was initially propagated among the faithful in local prayer groups. Ordained and lay preachers of both movements promoted a series of revivals in the province which drew an increasing number of followers into the evangelical fold.1 The first of these revivals was the Newlight- dominated Great Awakening of 1776-84. In general, Newlightism's greatest appeal was in the Planter townships even though it mutated by 1800 into a Baptist polity. Methodism, which had a fluctuating number of adherents among the visiting military forces at Halifax, had its stronghold in areas settled by British-born colonists, and increased in numbers with the successive waves of Loyalists coming to the province after 1783.2 Methodism was not confined, however, to segregated geographical areas of Nova Scotia. By the early nineteenth century, there were significant Methodist congregations composed primarily of Planters located throughout the Annapolis Valley and along the province's South Shore. Interesting questions are posed for historians when we consider why New Englanders and their descendants were attracted to what appeared to be essentially a foreign hierarchical religious-cultural movement which had broken from 1 Gordon Stewart and George Rawlyk, A People Highly Favoured of God: The Nova Scotia Yankees and the American Revolution (Toronto, 1972); J.M. -

Scottish Settlement and Land Plot Names and Settler Colonialism In

What’s in a name? Scottish Settlement and Land Plot Names and Settler Colonialism in Nineteenth Century Inverness County, Cape Breton. By Rachel L. Hart A Thesis submitted to Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, Nova Scotia in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History. © Copyright Rachel L. Hart, 2020 December, 2020, Halifax, Nova Scotia Approved: Dr. S. Karly Kehoe Supervisor Approved: Dr. Heather Green Examiner Approved: Dr. Don Nerbas Examiner Date: 10 December 2020 2 What’s in a name? Scottish Settlement and Land Plot Names and Settler Colonialism in Nineteenth Century Inverness County, Cape Breton. By Rachel L. Hart Abstract 10 December 2020 The application of place names by Scottish colonizers is a well-studied field. However, those studies focus on the identification and classification of such names, with little emphasis on how these names actually came to exist. This thesis provides an in-depth analysis of those that exist in Inverness County, exploring two types of names: those applied to settlements, settlement names; and those applied by individuals to land granted them, land plot names. Through analysis of land petitions, maps, and post office records, this thesis charts the settlement of places that would come to have Scottish names and the emergence of Scottish settlement and land plot names within Inverness County to demonstrate that these names were introduced as a result of large-scale Scottish settlement. This contrasts with the place names that can be found in other parts of the former British Empire such as Australia, New Zealand and even other parts of Canada where Scottish names came to exist as a result of Scottish colonial involvement as administrators, explorers and cartographers. -

Birds of the Nova Scotia— New Brunswick Border Region by George F

Birds of the Nova Scotia— New Brunswick border region by George F. Boyer Occasional Paper Number 8 Second edition Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Environnement Canada Wildlife Service Service de la Faune Birds of the Nova Scotia - New Brunswick border region by George F. Boyer With addendum by A. J. Erskine and A. D. Smith Canadian Wildlife Service Occasional Paper Number 8 Second edition Issued under the authority of the Honourable Jack Davis, PC, MP Minister of the Environment John S. Tener, Director Canadian Wildlife Service 5 Information Canada, Ottawa, 1972 Catalogue No. CW69-1/8 First edition 1966 Design: Gottschalk-)-Ash Ltd. 4 George Boyer banding a barn swallow in June 1952. The author George Boyer was born in Woodstock, New Brunswick, on August 24, 1916. He graduated in Forestry from the University of New Brunswick in 1938 and served with the Canadian Army from 1939 to 1945. He joined the Canadian Wildlife Service in 1947, and worked out of the Sackville office until 1956. During that time he obtained an M.S. in zoology from the University of Illinois. He car ried on private research from April 1956 until July 1957, when he rejoined CWS. He worked out of Maple, Ontario, until his death, while on a field trip near Aultsville. While at Sackville, Mr. Boyer worked chiefly on waterfowl of the Nova Scotia-New Brunswick border region, with special emphasis on Pintails and Black Ducks. He also studied merganser- salmon interrelationships on the Miramichi River system, Woodcock, and the effects on bird popu lations of spruce budworm control spraying in the Upsalquitch area. -

Beaubassin Acadian Families Speak

Development of the historic site of Beaubassin Acadian Families Speak Out Final report Submitted to the FAFA By its Advisory Committee December 2006 Editor’s notice: The following is the result of discussions, visits and research undertaken by Committee members, according to the interpreted mandate. This Report also contains, in due course, our standpoints as well as our recommendations. This Final Report has taken into consideration the feedback received after the handing of the Preliminary Report to the FAFA last September. Without contest to any founding elements, it is thus very similar to said text of the Preliminary Report. We thank the FAFA for entrusting us with a mandate of such importance. We now leave to you the challenges concerning the broadcasting and promotion of this Report, especially with follow-ups that are to be judged in the interest of the Acadian families. Paul-Pierre Bourgeois, Committee spokesperson Postal Address : 104 ch. Grande-Digue / Grande-Digue NB / E4R 4L4 E-mail : [email protected] Tel. : 506-576-9396 The Committee : Pierre Arsenault Gilles Babin Louis Bourgeois Paul-Pierre Bourgeois Jean-Claude Cormier Camille Gallant Jean Gaudet Gordon Hébert Alyre Richard Thelma Richard Section A INTRODUCTION A – 1 Creation of the Committee A – 1.1 During its May 13th 2006 meeting, the FAFA has approved Jean Gaudet’s proposal requesting 1° that the FAFA file opening on the subject of the Beaubassin historic village; and 2° that an advisory committee be formed under the leadership of the Bourgeois family as its councilors. A – 1.2 Said Advisory Committee having not received any other specific directive, representatives of the Bourgeois family, Louis and Paul-Pierre, have thus been entrusted with an open mandate according to their judgment. -

330 Pictou Antigonish Highlands Profile

A NOVA SCOTIA DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES PUBLICATION Ecodistrict Profile Ecological Landscape Analysis Summary Ecodistrict 330: Pictou Antigonish Highlands An objective of ecosystem-based management is to manage landscapes in as close to a natural state as possible. The intent of this approach is to promote biodiversity, sustain ecological processes, and support the long-term production of goods and services. Each of the province’s 38 ecodistricts is an ecological landscape with distinctive patterns of physical features. (Definitions of underlined terms are included in the print and electronic glossary.) This Ecological Landscape Analysis (ELA) provides detailed information on the forest and timber resources of the various landscape components of Pictou Antigonish Highlands Ecodistrict 330. The ELA also provides brief summaries of other land values, such as minerals, energy and geology, water resources, parks and protected areas, wildlife and wildlife habitat. This ecodistrict has been described as an elevated triangle separating the Northumberland Lowlands Ecodistrict 530 of Pictou County from the St. Georges Bay Ecodistrict 520 lowlands of Antigonish County. Generally, the highlands at their summit become a rolling plateau best exemplified by The Keppoch, an area once extensively settled and farmed. The elevation in the ecodistrict is usually 210 to 245 metres above sea level and rises to 300 metres at Eigg Mountain. The total area of Pictou Antigonish Highlands is 133,920 hectares. Private land ownership accounts for 75% of the ecodistrict, 24% is under provincial Crown management, and the remaining 1% includes water bodies and transportation corridors. A significant portion of the highlands was settled and cleared for farming by Scottish settlers beginning in the late 1700s with large communities at Rossfield, Browns Mountain, and on The Keppoch.