Durham E-Theses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2009 – 2014 NORTHUMBERLAND NATIONAL PARK

Part B – Strategy The North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2009 – 2014 NORTHUMBERLAND NATIONAL PARK Haydon Corbridge Haltwhistle A69 Bridge Bardon MIll 9 9 A6 A6 HEXHAM e P yn BRAMPTON W Allen R. T Banks Hallbankgate The Garden Lambley Station Talkin Tarn Viaduct B Highland Country Park 6 Slaley 3 Halton-lea-Gate Whiteld 0 Cattle Centre 6 A Talkin 6 8 t en Cold Fell w Castle Carrock South Whiteld Allendale er . D Tyne Moor R Valley Derwent Geltsdale RSPB East Allen Resr Shotley Beamish Museum Reserve R Valley . A686 Hexhamshire (12 miles) S Bridge R o Ninebanks R . Slaggyford . Common E u R E d t . h W a A CONSETT e s Cumrew B Pow n 6 T e t 8 y s 6 Blanchland 9 n t 2 Hill 9 Edmundbyers e West Allen A B 5 A l Country 6 Valley l Derwent e 4 l 1 l n Park 3 e Valley n Castleside Lanchester Alston 2C Armathwaite Croglin South C Tynedale Allenheads C Railway 2 C & The Hub Killhope A 6 8 6 A689 Museum Rookhope Stanhope 2C 68 C A Nenthead Common Waskerley Resr. Garrigill Nenthead Durham Thortergill Mines Dales Tunstall M Forge Cowshill Resr. 6 Kirkoswald Hartside Centre Lazonby W St John’s Stanhope P Chapel Eastgate Melmerby Fell Tow law Ireshopeburn Frosterley Wolsingham B Melmerby Weardale Westgate 6 4 Museum 1 2 W e a r d a l e Harehope Crook R Quarry Weardale R . T . ees Railway W Sea to Sea Cycle Route (C2C) Cross Fell B e 6 2 a Langwathby 7 r Great Dun Fell 7 Bollihope Common Cow Green B PENRITH 6 Reservoir 2 7 Blencarn 8 Langdon Beck Moor House - A66 Upper Teesdale Bowlees Visitor Centre Hamsterley Forest NNR Newbiggin PW High Force Chapel Rheged Cauldron Low Force Snout Te Middleton-in-Teesdale Woodland BISHOP Dufton e West s d a Auckland AUCKLAND High Cup Nick l e Ark on the Edge A 68 276 Romaldkirk Hilton B6 Grassholme Raby Castle Appleby-in- Resr. -

Download Chapter In

Flora and vegetation Margaret E Bradshaw The flora of Upper Teesdale is probably more widely known than that of any other area in Britain, and yet perhaps only a few of the thousands who visit the Dale each year realise the extent to which the vegetation and flora contribute to the essence of its character. In the valley, the meadows in the small walled fields extend, in the lower part, far up the south-facing slope, and, until 1957 to almost 570m at Grass Hill, then the highest farm in England. On the north face, the ascent of the meadows is abruptly cut off from the higher, browner fells by the Whin Sill cliff, marked by a line of quarries. Below High Force, the floor of the valley has a general wooded appearance which is provided by the small copses and the many isolated trees growing along the walls and bordering the river. Above High Force is a broader, barer valley which merges with the expansive fells leading up to the characteristic skyline of Great Dun Fell, Little Dun Fell and Cross Fell. Pennine skyline above Calcareous grassland and wet bog, Spring gentian Red Sike Moss © Margaret E Bradshaw © Geoff Herbert Within this region of fairly typical North Pennine vegetation is a comparatively small area which contains many species of flowering plants, ferns, mosses, liverworts and lichens which can be justifiably described as rare. The best known is, of course, the spring gentian (Gentiana verna), but this is only one of a remarkable collection of plants of outstanding scientific value. -

Word Catalogue.Docx

H.J. Pugh & Co. HAZLE MEADOWS AUCTION CENTRE, LEDBURY, HEREFORDSHIRE HR8 2LP ENGINEERING MACHINERY, LATHES, MILLS, SAWS, DRILLS AND COLLECTABLE TOOLS, SEASONED AND GREEN SAWN TIMBER SATURDAY 2nd JANUARY 9:30AM Viewing 29th 30th & 31st Dec 9am - 1pm and 8am onward morning of sale 10% buyers premium + VAT 2 Rings RING 1 1-450 (sawn timber, workshop tools, machinery and lathes) 9:30am RING 2 501-760 (specialist woodworking tools and engineering tools) 10am Caterer in attendance LIVE AND ONLINE VIA www.easyliveauction.com Hazle Meadows Auction Centre, Ledbury, Herefordshire, HR8 2AQ Tel: (01531) 631122. Fax: (01531) 631818. Mobile: (07836) 380730 Website: www.hjpugh.co.uk E-mail: [email protected] CONDITIONS OF SALE 1. All prospective purchasers to register to bid and give in their name, address and telephone number, in default of which the lot or lots purchased may be immediately put up again and re-sold 2. The highest bidder to be the buyer. If any dispute arises regarding any bidding the Lot, at the sole discretion of the auctioneers, to be put up and sold again. 3. The bidding to be regulated by the auctioneer. 4. In the case of Lots upon which there is a reserve, the auctioneer shall have the right to bid on behalf of the Vendor. 5. No Lots to be transferable and all accounts to be settled at the close of the sale. 6. The lots to be taken away whether genuine and authentic or not, with all faults and errors of every description and to be at the risk of the purchaser immediately after the fall of the hammer but must be paid for in full before the property in the goods passes to the buyer. -

March 1999 No

The Area meet wrap-up ► 4 - - Spiral screwdrivers ► 14 r1stm1 Old signboards ► 16 Auxiliary news ► 22 A Publication of the Mid-West Tool Collector's Association M-WTCA.ORG Wooden patent model of a J. Siegley plane. Owned by Ron Cushman. March 1999 No. 94 Chaff N. 94 March, 1999 Copyright 1999 by Mid-West Tool Collectors Assodation, Inc. All rights reserved. From the President Editor Mary Lou Stover S76Wl9954 Prospect Dr. I have just Muskego, WI 53150 a new feature in this issue. Check out Associate Editor Roger K. Smith returned from a the list and ask yourself if you might be Contributing Editor Thomas Lamond PAST meeting in San of help. I am sure that most of those Advertising Manager Paul Gorham Diego where I was making a study do not actually own THE GRISTMILL is the official publication of the Mid-West Tool Collectors Association, Inc. Published 4uar1erly in March. June, welcomed by PAST each piece they include in the study. September and December. "Chief' Laura Pitney The purpose of the association is lo promote the preservation, You might have a tool the researchers study and understanding of ancient tools, implements and devices and other members. need to know about. If you think you of farm, home, industry and shop of lhc pioneers; also, lo study the crafts in which these objects were used and the craftsmen who The weather was can help in an area, please contact one of used them; and to share knowledge and understanding with others, especially where ii may benefit rcsloralion, museums and like quite different than the authors. -

This Parish Occupies an Extensive Tract in the North-Eastern Corner Of

DUFTON PARISH. 183 ) • Area, according to Ordnance Survey, 16,848 acres; area under assessment, 4,266 acres. Rateable value, £4,542; population, 414. • This parish occupies an extensive tract in the north-eastern corner of the county, stretching from the confines of Durham west ward a distance of about eight miles, and from north to south about five miles. It is bounded on the north by Milbourn Forest; on the west by Long Marton ; on the south by Bongate parish ; and on the east by the river Tees, which here expands into a fine broad sheet of water called The Wheel. From this lake the water is precipitated down a steep incline ; and from its resemblance to the discharge of a liquid from some huge vessel, the fall has been named Caldron Snout. Numerous offshoots from the Pennine Range and other detached mountain masses cover the parish, giving it a decidedly Alpine -character. Among these hills are reared great numbers of a superior breed of black-faced mountain sheep. Though wanting in those picturesque and romantic effects which form such attractive features in much of the mountain scenery of the lake land, there are several pleasing patches of landscape and other intere10ting spots in this dis trict well worthy of notice. Of late years the locality has been much frequented by tourists on their way to the lakes from the counties of Durham and Yorkshire. The route generally taken is by way of High Force to Caldron Snout, then up Maize at the base of Mickle Fell, and across Hycup (High Cup) plain (where perchance the traveller may experience the effects of the remarkable Helm wind) to Hycup Gill, one of the grandest sights in the Pennines. -

Monthly Messenger

Monthly Messenger Central Minnesota Woodworker’s Association Volume 6 Issue 11 November 2006 Habitat for Humanity CMWA Meeting Recap by Ron McKeever Sauk Rapids-Rice Middle School on Oct 18th, 2006 at 7PM Recap adapted from secretary’s meeting The work on the cabinets at the Habitat for Humanity minutes house is complete. We started this project of building the cabinets for the kitchen and 2 bathrooms in July Hand Plane Tune-up and have worked 2 evenings a week until last Roland Johnson provided a helpful demonstration Saturday, when we wrapped up the project with the on tuning up a hand plane. installation of the island. With the help of a bunch of See Hand Plane Tune-up page 3 dedicated woodworkers and some hard work we were able to supply a very nice set of cabinets and CMWA Student Outreach have some fun at the same time. The following is a Student Outreach Program Chairman, John list of the people that made this all possible - Thank Kirchoff, is looking for at least two more volunteers You all very much! Tom Homan, Cindy Johnson, to assist in the mentoring of students at the Tom Moore, Gredo Goldenstein, Dave Schwanke, upcoming Fall Outreach Program beginning Thomas L. Homan, Scott Randall, Brad Knolls, Tom Tuesday, November 14th. The program will run for Doom, Tom Zak, Angelo Gambrino, Darren four consecutive Tuesday nights, November 14th, McKeever, Richard Beemer, Rollie Johnson, Alex 21st, 28th & December 5th, from 7:00 pm to 8:30 Neussendorfer, Ron McKeever, Eddie Och. pm, at the Sauk Rapids-Rice Middle School Woodshop. -

ELENA URIOSTE Finds Her Violin Soul Mate

Brush Up Your Bow Hold Special Focus: ADULT AMATEUR PLAYERS Be Brave! Write Your Own Songs LEONARD BERNSTEIN: Celebrating the String Works Enter JOSHUA BELL’s ‘Fantasy’ World ELENA URIOSTE Finds her Violin Soul Mate August 2018 No. 280 StringsMagazine.com Ascenté violin strings elevate the sophistication of my students’ tone. -Dr. Charles Laux, Alpharetta, GA D’Addario Ascenté is the first synthetic core string designed to elevate your craft. It’s the only string that combines the sophisticated tone, unbeatable pitch stability, and superior durability required by the progressing player. The next-level string for the next-level violinist. I started my musical journey twelve years ago, continuing to love what I do. I am extremely elated that snow violin has fulfilled my life with its intensity, power and beauty. Yaas Azmoudeh www.snowviolin.com 1-800-645-0703 [email protected] 16 SPECIAL FOCUS FEATURES Adult Amateur Players 16 Leonard Bernstein at 100 36 Celebrating the legendary A New World composer-conductor’s string works On the benefits and unbridled loyalty to the music of starting cello By Thomas May lessons at age 63 By Judy Pollard Smith 23 Journey to the Highlands 38 Joshua Bell’s new recording with Lifelong Wish the Academy of St Martin in the It’s never too late to pick up Fields pairs Bruch’s Violin Concerto an instrument—here are No. 1 with ‘Scottish Fantasy’ 5 tips for adult beginners By Inge Kjemtrup By Miranda Wilson 28 41 Prized Possessions Better Together String players and makers Encouragement and advice on their most sentimental for advancing amateur string-related items orchestral musicians Compiled by Stephanie Powell By Emily Wright & Megan Westberg 44 How to Start an Adult Chamber-Music Ensemble AUGUST These tips can help ensure 2018 a successful experience VOLUME XXXIII, NUMBER 1, ISSUE 280 By Greg Cahill COVER: ELENA URIOSTE BERNSTEIN—WILLIAM P. -

Moor House - Upper Teesdale B6278 Widdybank Farm, Langdon Beck, River Tees NNR Forest-In-Teesdale, B6277 Barnard Castle, Moor House – Cow Green Middleton- Co

To Alston For further information A686 about the Reserve contact: A689 The Senior Reserve Manager Moor House - Upper Teesdale B6278 Widdybank Farm, Langdon Beck, River Tees NNR Forest-in-Teesdale, B6277 Barnard Castle, Moor House – Cow Green Middleton- Co. Durham DL12 0HQ. Reservoir in-Teesdale To Penrith Tel 01833 622374 Upper Teesdale Appleby-in- National Nature Reserve Westmorland B6276 0 5km B6260 Brough To Barnard Castle B6259 A66 A685 c Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Kirkby Stephen Natural England 100046223 2009 How to get there Front cover photograph: Cauldron Snout The Reserve is situated in the heart of © Natural England / Anne Harbron the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is in two parts on either Natural England is here to conserve and side of Cow Green Reservoir. enhance the natural environment, for its intrinsic value, the wellbeing and A limited bus service stops at Bowlees, enjoyment of people and the economic High Force and Cow Green on request. prosperity that it brings. There is no bus service to the Cumbria © Natural England 2009 side of the Reserve. ISBN 978-1-84754-115-1 Catalogue Code: NE146 For information on public transport www.naturalengland.org.uk phone the local Tourist Information Natural England publications are available Centres as accessible pdfs from: www.naturalengland.org.uk/publications Middleton-in-Teesdale: 01833 641001 Should an alternative format of this publication be required, please contact Alston: 01434 382244 our enquiries line for more information: 0845 600 3078 or email Appleby: 017683 51177 [email protected] Alston Road Garage [01833 640213] or Printed on Defra Silk comprising 75% Travel line [0870 6082608] can also help. -

Management Plan for Catlett Islands: Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve - Virginia

COMMONWEALTH of VIRGINIA Management Plan for Catlett Islands: Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve - Virginia Prepared by: Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Division of Natural Heritage Natural Heritage Technical Report 05-04 2005 Management Plan for Catlett Islands - 2005 i Management Plan for Catlett Islands - 2005 Management Plan for Catlett Islands: Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve -Virginia 2005 Natural Heritage Technical Report 05-04 Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation Division of Natural Heritage 217 Governor Street Richmond, Virginia 23219 (804) 786-7951 This document may be cited as follows: Erdle, S. Y. and K. E. Heffernan. 2005. Management Plan for Catlett Islands: Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve-Virginia. Natural Heritage Technical Report #05- 04. Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation, Division of Natural Heritage. Richmond, Virginia. 35 pp. plus appendices. ii Management Plan for Catlett Islands - 2005 iii Management Plan for Catlett Islands - 2005 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................ iv PLAN SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................1 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................................1 -

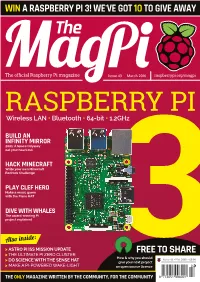

Win a Raspberry Pi 3!We've Got 1Oto Give Away

WIN A RASPBERRY PI 3! WE'VE GOT 1O TO GIVE AWAY Issue 43 Issue • Mar 2016 Mar The official Raspberry Pi magazine Issue 43 March 2016 raspberrypi.org/magpi RASPBERRY PI Wireless LAN • Bluetooth • 64-bit • 1.2GHz BUILD AN INFINITY MIRROR 2001: A Space Odyssey eat your heart out HACK MINECRAFT Write your own Minecraft Bedrock Challenge PLAY CLEF HERO Make a music game with the Piano HAT DIVE WITH WHALES The award-winning Pi project explained Also inside: > ASTRO PI ISS MISSION UPDATE > THE ULTIMATE PI ZERO CLUSTER FREE TO SHARE How & why you should Issue 43 • Mar 2016 • £5.99 > DO SCIENCE WITH THE SENSE HAT give your next project > MAKE A PI-POWERED WAKE-LIGHT an open source licence 03 THE ONLY MAGAZINE WRITTEN BY THE COMMUNITY, FOR THE COMMUNITY 9 772051 998001 Expand your Pi Stackable expansion boards for the Raspberry Pi Serial Pi Plus RS232 serial communication board. Control your Raspberry Pi over RS232 or connect to external serial accessories. Breakout Pi Plus The Breakout Pi Plus is a useful and versatile prototyping expansion board for the Raspberry Pi ADC Differential Pi 8 channel 18 bit analogue to digital converter. I2C address selection allows you to add up to 32 analogue inputs to your Raspberry Pi. IO Pi Plus 32 digital 5V inputs or outputs. I2C address selection allows you to stack up to 4 IO Pi Plus boards on your Raspberry Pi giving you 128 digital inputs or outputs. RTC Pi Plus Real-time clock with battery backup and 5V I2C level converter for adding external 5V I2C devices to your Raspberry Pi. -

Groverake at Risk

Reg. Charity No. 517647 Newsletter No 87 March 2016 Groverake at Risk Photo: Jean Thornley Most of the former lead and fluorspar mining site near Rookhope, including the iconic headgear, is set to be demolished by September 2016. A committee has been formed under the name of ‘Friends of Groverake’ and it will attempt to preserve the headgear. Friends of Killhope support this group and up to date information can be seen on their Facebook page: www.facebook.com/Friendsofgroverake. 1 Reminders Message from your Membership Secretary Please can members who pay by standing order check that their bank is paying the correct amount. Please see the membership form on the back page for current fees. Thank you. Message from your Newsletter Editor Thank you to all who have contributed articles for this newsletter. Please send submissions for the next newsletter to Richard Manchester at [email protected] or by post to Vine House, Hedleyhope, Bishop Auckland, DL13 4BN. Contents The Buddle House Wheel – Our Opportunity to Contribute to the Museum’s Future………...... 3 Linda Brown – Our New Treasurer……………………………….............................................. 4 Lead Shipments from North-East Ports to Overseas Destinations in 1676.......................... .. 5 Committee Contacts............................................................................................................... 13 Book Review: Images of Industry by Ian Forbes.................................................................. .. 14 Bryan Chambers.................................................................................................................... -

Knowing Weather in Place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell

Veale, L., Endfield, G., and Naylor, S. (2014) Knowing weather in place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell. Journal of Historical Geography, 45 . pp. 25-37. ISSN 0305-7488 Copyright © 2014 The Authors http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/99540 Deposited on: 19 November 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Journal of Historical Geography 45 (2014) 25e37 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Historical Geography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhg Knowing weather in place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell Lucy Veale a,*, Georgina Endfield a and Simon Naylor b a University of Nottingham, School of Geography, University Park, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK b University of Glasgow, School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, East Quadrangle, University Avenue, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK Abstract The Helm Wind of Cross Fell, North Pennines, is England’s only named wind. As a product of the particular landscape found at Cross Fell, the Helm is a true local wind, and a phenomenon that has come to assume great cultural as well as environmental significance in the region and beyond. In this paper we draw on material from county histories, newspaper archives, and documents relating to investigations of the Helm Wind that were conducted by the Royal Meteorological Society between 1884 and 1889, and by British climatologist Gordon Manley (1908e1980), between 1937 and 1939, to document attempts to observe, measure, understand and explain this local wind over a period of 200 years. We show how different ways of knowing the Helm relate to contemporary practices of meteorology, highlighting the shifts that took place in terms of what constituted credible meteorological observation.