Groverake at Risk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2009 – 2014 NORTHUMBERLAND NATIONAL PARK

Part B – Strategy The North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty Management Plan 2009 – 2014 NORTHUMBERLAND NATIONAL PARK Haydon Corbridge Haltwhistle A69 Bridge Bardon MIll 9 9 A6 A6 HEXHAM e P yn BRAMPTON W Allen R. T Banks Hallbankgate The Garden Lambley Station Talkin Tarn Viaduct B Highland Country Park 6 Slaley 3 Halton-lea-Gate Whiteld 0 Cattle Centre 6 A Talkin 6 8 t en Cold Fell w Castle Carrock South Whiteld Allendale er . D Tyne Moor R Valley Derwent Geltsdale RSPB East Allen Resr Shotley Beamish Museum Reserve R Valley . A686 Hexhamshire (12 miles) S Bridge R o Ninebanks R . Slaggyford . Common E u R E d t . h W a A CONSETT e s Cumrew B Pow n 6 T e t 8 y s 6 Blanchland 9 n t 2 Hill 9 Edmundbyers e West Allen A B 5 A l Country 6 Valley l Derwent e 4 l 1 l n Park 3 e Valley n Castleside Lanchester Alston 2C Armathwaite Croglin South C Tynedale Allenheads C Railway 2 C & The Hub Killhope A 6 8 6 A689 Museum Rookhope Stanhope 2C 68 C A Nenthead Common Waskerley Resr. Garrigill Nenthead Durham Thortergill Mines Dales Tunstall M Forge Cowshill Resr. 6 Kirkoswald Hartside Centre Lazonby W St John’s Stanhope P Chapel Eastgate Melmerby Fell Tow law Ireshopeburn Frosterley Wolsingham B Melmerby Weardale Westgate 6 4 Museum 1 2 W e a r d a l e Harehope Crook R Quarry Weardale R . T . ees Railway W Sea to Sea Cycle Route (C2C) Cross Fell B e 6 2 a Langwathby 7 r Great Dun Fell 7 Bollihope Common Cow Green B PENRITH 6 Reservoir 2 7 Blencarn 8 Langdon Beck Moor House - A66 Upper Teesdale Bowlees Visitor Centre Hamsterley Forest NNR Newbiggin PW High Force Chapel Rheged Cauldron Low Force Snout Te Middleton-in-Teesdale Woodland BISHOP Dufton e West s d a Auckland AUCKLAND High Cup Nick l e Ark on the Edge A 68 276 Romaldkirk Hilton B6 Grassholme Raby Castle Appleby-in- Resr. -

Download Chapter In

Flora and vegetation Margaret E Bradshaw The flora of Upper Teesdale is probably more widely known than that of any other area in Britain, and yet perhaps only a few of the thousands who visit the Dale each year realise the extent to which the vegetation and flora contribute to the essence of its character. In the valley, the meadows in the small walled fields extend, in the lower part, far up the south-facing slope, and, until 1957 to almost 570m at Grass Hill, then the highest farm in England. On the north face, the ascent of the meadows is abruptly cut off from the higher, browner fells by the Whin Sill cliff, marked by a line of quarries. Below High Force, the floor of the valley has a general wooded appearance which is provided by the small copses and the many isolated trees growing along the walls and bordering the river. Above High Force is a broader, barer valley which merges with the expansive fells leading up to the characteristic skyline of Great Dun Fell, Little Dun Fell and Cross Fell. Pennine skyline above Calcareous grassland and wet bog, Spring gentian Red Sike Moss © Margaret E Bradshaw © Geoff Herbert Within this region of fairly typical North Pennine vegetation is a comparatively small area which contains many species of flowering plants, ferns, mosses, liverworts and lichens which can be justifiably described as rare. The best known is, of course, the spring gentian (Gentiana verna), but this is only one of a remarkable collection of plants of outstanding scientific value. -

This Parish Occupies an Extensive Tract in the North-Eastern Corner Of

DUFTON PARISH. 183 ) • Area, according to Ordnance Survey, 16,848 acres; area under assessment, 4,266 acres. Rateable value, £4,542; population, 414. • This parish occupies an extensive tract in the north-eastern corner of the county, stretching from the confines of Durham west ward a distance of about eight miles, and from north to south about five miles. It is bounded on the north by Milbourn Forest; on the west by Long Marton ; on the south by Bongate parish ; and on the east by the river Tees, which here expands into a fine broad sheet of water called The Wheel. From this lake the water is precipitated down a steep incline ; and from its resemblance to the discharge of a liquid from some huge vessel, the fall has been named Caldron Snout. Numerous offshoots from the Pennine Range and other detached mountain masses cover the parish, giving it a decidedly Alpine -character. Among these hills are reared great numbers of a superior breed of black-faced mountain sheep. Though wanting in those picturesque and romantic effects which form such attractive features in much of the mountain scenery of the lake land, there are several pleasing patches of landscape and other intere10ting spots in this dis trict well worthy of notice. Of late years the locality has been much frequented by tourists on their way to the lakes from the counties of Durham and Yorkshire. The route generally taken is by way of High Force to Caldron Snout, then up Maize at the base of Mickle Fell, and across Hycup (High Cup) plain (where perchance the traveller may experience the effects of the remarkable Helm wind) to Hycup Gill, one of the grandest sights in the Pennines. -

Moor House - Upper Teesdale B6278 Widdybank Farm, Langdon Beck, River Tees NNR Forest-In-Teesdale, B6277 Barnard Castle, Moor House – Cow Green Middleton- Co

To Alston For further information A686 about the Reserve contact: A689 The Senior Reserve Manager Moor House - Upper Teesdale B6278 Widdybank Farm, Langdon Beck, River Tees NNR Forest-in-Teesdale, B6277 Barnard Castle, Moor House – Cow Green Middleton- Co. Durham DL12 0HQ. Reservoir in-Teesdale To Penrith Tel 01833 622374 Upper Teesdale Appleby-in- National Nature Reserve Westmorland B6276 0 5km B6260 Brough To Barnard Castle B6259 A66 A685 c Crown copyright. All rights reserved. Kirkby Stephen Natural England 100046223 2009 How to get there Front cover photograph: Cauldron Snout The Reserve is situated in the heart of © Natural England / Anne Harbron the North Pennines Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is in two parts on either Natural England is here to conserve and side of Cow Green Reservoir. enhance the natural environment, for its intrinsic value, the wellbeing and A limited bus service stops at Bowlees, enjoyment of people and the economic High Force and Cow Green on request. prosperity that it brings. There is no bus service to the Cumbria © Natural England 2009 side of the Reserve. ISBN 978-1-84754-115-1 Catalogue Code: NE146 For information on public transport www.naturalengland.org.uk phone the local Tourist Information Natural England publications are available Centres as accessible pdfs from: www.naturalengland.org.uk/publications Middleton-in-Teesdale: 01833 641001 Should an alternative format of this publication be required, please contact Alston: 01434 382244 our enquiries line for more information: 0845 600 3078 or email Appleby: 017683 51177 [email protected] Alston Road Garage [01833 640213] or Printed on Defra Silk comprising 75% Travel line [0870 6082608] can also help. -

Knowing Weather in Place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell

Veale, L., Endfield, G., and Naylor, S. (2014) Knowing weather in place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell. Journal of Historical Geography, 45 . pp. 25-37. ISSN 0305-7488 Copyright © 2014 The Authors http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/99540 Deposited on: 19 November 2014 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Journal of Historical Geography 45 (2014) 25e37 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Historical Geography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhg Knowing weather in place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell Lucy Veale a,*, Georgina Endfield a and Simon Naylor b a University of Nottingham, School of Geography, University Park, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK b University of Glasgow, School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, East Quadrangle, University Avenue, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK Abstract The Helm Wind of Cross Fell, North Pennines, is England’s only named wind. As a product of the particular landscape found at Cross Fell, the Helm is a true local wind, and a phenomenon that has come to assume great cultural as well as environmental significance in the region and beyond. In this paper we draw on material from county histories, newspaper archives, and documents relating to investigations of the Helm Wind that were conducted by the Royal Meteorological Society between 1884 and 1889, and by British climatologist Gordon Manley (1908e1980), between 1937 and 1939, to document attempts to observe, measure, understand and explain this local wind over a period of 200 years. We show how different ways of knowing the Helm relate to contemporary practices of meteorology, highlighting the shifts that took place in terms of what constituted credible meteorological observation. -

Alston Cycle Route: Cross Fell (Mountain Bike Ride)

Alston Cycle Route: Cross Fell (Mountain Bike Ride) Cross Fell and its near neighbour Great Dun Fell are ringed by an amazing network of high- level bridleways. They cross wild and exposed moorland and reach a considerable height making them the highest mountain bike routes in England, outside the Lake District. These routes are not for the fainthearted, particularly first timers to the area as they cross high and exposed moorland, and the distances and height gain involved in completing a loop are considerable. The best introduction to the style of riding they offer is to tackle an out and back ride up the bridleway that climbs to the northern shoulder of Cross Fell from the lovely village of Garrigill. There is a fair amount of height to gain on this route but it is achieved over eleven kilometres which gives most of the climbs a moderate and mostly cycle-able gradient. The majority of the riding is along access track which is stony but wellmaintained, with the balance being on stony single track and a final short section on open fell side. The climb is mitigated by superb wide ranging views and interesting old mine workings passed on the way up. The descent is world class and gives long and fast bursts interspersed with cruising freewheels. There are a couple of rock garden sections to deal with through the old mine workings, and some drainage channels to negotiate, but mostly the technicalities are at the softer end of the range. Remember to always stick to the bridleways as this is a conservation area. -

North Pennine Ridge South Section

Route Information Distance 23 kilometres (14.5 miles) Ascent 1050 metres (3450 feet) Time needed 9 hours (approx) Start point Dufton village green, approx 3½ miles north of Appleby-in-Westmorland. Parking available in the small car park just off the village green at NY 689 249 Public Transport Dufton is served by bus routes 573 and 625 (limited service) © Crown Copyright 2011. All rights reserved. Licence no 100019596 (Southern Section) Part of this route crosses open access land on a managed grouse moor, over which DOGS ARE NOT ALLOWED. This area is coloured red on the accompanying map. Access may be further restricted during the nesting season and at other times of the year. To avoid disappointment, please visit www.countrysideaccess.gov.uk to get the latest restriction information, before you set out. Hurning Lane follows naturally on offering fine views of Dufton Pike, with further gates and stiles to approach and pass Halsteads, a traditional farmstead now used for stock- handling. This is the last hint of settlement on the walk until Hartside Café. From the gate beside the buildings the Pennine Way leads up the open track, flanked by a remnant hedge. The track curves downhill to arrive at a wall-stile and Currick near Fiend’s Fell, Hartside gate, promptly step over the clapper-bridge spanning Great Rundale Beck. Follow on In The North Pennines of Outstanding Natural Area Beauty & European Geopark Begin from the village car park at the with the wallside track, gradually rising to a eastern end of the attractive, wide, tree- kissing-gate, the upper walled lane portion lined green. -

Oresome North Pennines: Site Overview Cashwell Hush and Lead Mining Remains, and Upper Slatesike Lead Mine and Ore Works

OREsome North Pennines: Site Overview Cashwell hush and lead mining remains, and Upper Slatesike lead mine and ore works Fig.1: Upper Slatesike, looking towards Great Dun Fell SAM list entry numbers: 1015838 and 1015837 Other designations: North Pennine Moors SPA/ Moor House-Upper Teesdale SAC Grid ref.: NY711359 and NY707353 County: Cumbria District/parish: Eden, Culgaith Altitude: 660-700m Habitats: moorland sheep pasture, upland heath Highlights Archaeology: The remains at Cashwell are a good example of those found on a dispersed lead mining landscape, as opposed to those at nucleated mines which developed through the 19th century. The monument forms a core area of well preserved features within a wider landscape, believed to be of 18th century date, making this site nationally rare. Upper Slatesike is another 18th century lead mine, with the characteristic barrow tipped spoil heaps. There is a fine example of a manually powered oreworks, with its network of water channels, the remains of stone built structures and discrete spreads of ore processing waste. This monument is considered to be one of the best preserved examples of an 18th or early 19th century lead mine known in Northern England. 1 Botany: Cashwell Hush is an important site for its lichen interest, which benefits from the lack of disturbance in a remote location and from the cool damp climate on Cross Fell. No botanical interest was found, and this is consistent with other high altitude sites in the North Pennines. Geology: the composition of the Cornriggs and Cashwell veins is unusual within the overall context of the orefield. -

Great Dun Fell

Troublesome wind A self guided walk in the North Pennines Explore the spectacular scenery around Great Dun Fell Discover why it experiences some of the most extreme weather in England Hear some remarkable accounts of Britain’s only named wind Find out about one man’s lifetime spent observing the weather .discoveringbritain www .org ies of our land the stor scapes throug discovered h walks 2 Contents Introduction 4 Route overview 5 Practical information 6 Detailed route maps 7 Directions 9 Credits 14 © The Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers, London, 2013 Discovering Britain is a project of the Royal Geographical Society (with IBG) The digital and print maps used for Discovering Britain are licensed to the RGS-IBG from Ordnance Survey 3 Troublesome wind Discover the unique weather of the North Pennines Introduction Explore the spectacular scenery of the North Pennines. Discover why they experience some of the most extreme weather in England. Hear some remarkable accounts of Britain’s only named wind with a reputation for blowing over horses and humans. Find out about one man’s determination to observe and measure it. This walk in Cumbria follows the Pennine Way to the summit of Great Dun Fell, the second highest hill in the View towards Knock Pike and the Lake District Pennines. Jenny Lunn © RGS-IBG Discovering Britain It tells the story of Gordon Manley, the geographer who pioneered the collection of meteorological data. Visit the site of one of his weather stations on the summit. Discover what he measured and why he kept returning to this unique landscape. -

FUTURE WALKS DUFTON/APPLEBY Coaches Leave Dufton at 5.30Pm If

www.pdwc.org Vol: 25 Issue 4 20 March 2011 DUFTON/APPLEBY Coaches leave Dufton at 5.30pm FUTURE WALKS Coach Walks 8.30am start : 5.30pm return Sun 17 Apr Clapham / Settle A: Val Walmsley B+: Dave Thornton B: Derek Lowe C: Joyce Bradbury 8.00am start : 5.30pm return Sun 15 May Pooley Bridge A: Graham Hogg B+: Tony Ingham B: Dave Tilleray C: Roy Smith Thursday Car Walks 10.30am start See our web site for details of the Thursday Car Walks Thurs 14 Apr Slaidburn B Walk with Dave Thornton Meet at the village car park Thurs 12 May Levens B Walk with Jackie & Sheila Meet at GR507867 Sunday Car Walks 10.30am start Sun 3 Apr Garstang/Barnacre/Calder Vale B Walk with Chris Metcalfe Meet at the riverside car park 10½ miles / 16.9km, cumulative ascent 650ft / 198m. Relatively easy walking – just a few stiles!!! Starting at the (Pay & Display) Riverside Car Park this walk will take us through Barnacre to Calder Vale via field footpaths, farm tracks and quiet country roads, returning down Nicky Nook valley and along the Wyre Way. If the weather is favourable there will be great views of the countryside, from the Lake District in the north round to the Welsh Mountains in the south. Plenty of local history and wildlife to observe as well. There are toilets at the car park in Garstang but you will find far nicer ones in the Booths store on the ring road. Sun 3 Apr Eccleston C Walk with Derek Lowe Meet near Eccleston Church (From Preston take the Penwortham By-Pass as far as the Southport Road, turn right and take the 2 nd left into New Lane.) 5½ miles / 8.9km with no climbing. -

The Helm Wind of Cross Fell

Journal of Historical Geography 45 (2014) 25e37 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Historical Geography journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhg Knowing weather in place: the Helm Wind of Cross Fell Lucy Veale a,*, Georgina Endfield a and Simon Naylor b a University of Nottingham, School of Geography, University Park, Nottingham NG7 2RD, UK b University of Glasgow, School of Geographical and Earth Sciences, East Quadrangle, University Avenue, Glasgow G12 8QQ, UK Abstract The Helm Wind of Cross Fell, North Pennines, is England’s only named wind. As a product of the particular landscape found at Cross Fell, the Helm is a true local wind, and a phenomenon that has come to assume great cultural as well as environmental significance in the region and beyond. In this paper we draw on material from county histories, newspaper archives, and documents relating to investigations of the Helm Wind that were conducted by the Royal Meteorological Society between 1884 and 1889, and by British climatologist Gordon Manley (1908e1980), between 1937 and 1939, to document attempts to observe, measure, understand and explain this local wind over a period of 200 years. We show how different ways of knowing the Helm relate to contemporary practices of meteorology, highlighting the shifts that took place in terms of what constituted credible meteorological observation. We also acknowledge the overlapping nature of these ways of knowing and the persistence of multiple testimonies about the Helm and its effects. Ó 2014 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/). -

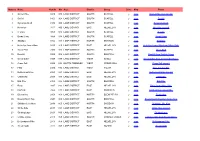

Nutt No Name Nutt Ht Alt Area District Group Done Map Photo 1 Scafell

Nutt no Name Nutt ht Alt Area District Group Done Map Photo 1 Scafell Pike 3209 978 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Scafell Pike from Scafell 2 Scafell 3163 964 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Scafell 3 Symonds Knott 3146 959 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Symonds Knott 4 Helvellyn 3117 950 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Helvellyn summit 5 Ill Crag 3068 935 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Ill Crag 6 Broad Crag 3064 934 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Broad Crag 7 Skiddaw 3054 931 LAKE DISTRICT NORTH SKIDDAW y map Skiddaw 8 Helvellyn Lower Man 3035 925 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Helvellyn Lower Man from White Side 9 Great End 2986 910 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH SCAFELL y map Great End 10 Bowfell 2959 902 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH BOWFELL y map Bowfell from Crinkle Crags 11 Great Gable 2949 899 LAKE DISTRICT WEST GABLE y map Great Gable from the Corridor Route 12 Cross Fell 2930 893 NORTH PENNINES WEST CROSS FELL y map Cross Fell summit 13 Pillar 2926 892 LAKE DISTRICT WEST PILLAR y map Pillar from Kirk Fell 14 Nethermost Pike 2923 891 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Nethermost Pike summit 15 Catstycam 2920 890 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Catstycam 16 Esk Pike 2904 885 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH BOWFELL y map Esk Pike 17 Raise 2897 883 LAKE DISTRICT EAST HELVELLYN y map Raise from White Side 18 Fairfield 2864 873 LAKE DISTRICT EAST FAIRFIELD y map Fairfield from Gavel Pike 19 Blencathra 2858 868 LAKE DISTRICT NORTH BLENCATHRA y map Blencathra 20 Bowfell North Top 2841 866 LAKE DISTRICT SOUTH BOWFELL y map Bowfell North Top from