Sample Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charitably Chic Lynn Willis

Philadelphia University Spring 2007 development of (PRODUCT) RED, a campaign significantly embraced by the fashion community. Companies working with Focus on . Alumni Focus on . Industry News (PRODUCT) RED donate a large percentage of their profits to the Global Fund to fight Lynn Willis Charitably Chic AIDS. For example, Emporio Armani’s line donates 40 percent of the gross profit By Sara Wetterlin and Chaisley Lussier By Kelsey Rose, Erin Satchell and Holly Ronan margin from its sales and the GAP donates Lynn Willis 50 percent. Additionally, American Express, Trends in fashion come and go, but graduated perhaps the first large company to join the fashions that promote important social from campaign, offers customers its RED card, causes are today’s “it” items. By working where one percent of a user’s purchases Philadelphia with charitable organizations, designers, University in goes toward funding AIDS research and companies and celebrities alike are jumping treatment. Motorola and Apple have also 1994 with on the bandwagon to help promote AIDS a Bachelor created red versions of their electronics and cancer awareness. that benefit the cause. The results from of Science In previous years, Ralph Lauren has the (PRODUCT) RED campaign have been in Fashion offered his time and millions of dollars to significant, with contributions totaling over Design. Willis breast cancer research and treatment, which $1.25 million in May 2006. is senior includes the establishment of health centers Despite the fashion industry’s focus on director for the disease. Now, Lauren has taken image, think about what you can do for of public his philanthropy further by lending his someone else when purchasing clothes relations Polo logo to the breast cancer cause with and other items. -

A Pattern Language for Costumes in Films

Institute of Architecture of Application Systems A Pattern Language for Costumes in Films David Schumm1, Johanna Barzen2, Frank Leymann1, and Lutz Ellrich2 1 Institute of Architecture of Application Systems, University of Stuttgart, Germany {schumm, leymann}@iaas.uni-stuttgart.de 2 Institut für Theater-, Film- und Fernsehwissenschaft, Universität zu Köln, Germany {jbarzen, lutz.ellrich}@uni-koeln.de : @inproceedings,{INPROC42012419,, ,,,author,=,{David,Schumm,and,Johanna,Barzen,and,Frank,Leymann,and,Lutz, ,Ellrich},, ,,,title,=,{{A,Pattern,Language,for,Costumes,in,Films}},, ,, ,booktitle,=,{Proceedings,of,the,17th,European,Conference,on, ,Pattern,Languages,of,Programs,(EuroPLoP,2012)},, ,,,editor,=,{Christian,Kohls,and,Andreas,Fiesser},, ,,,address,=,{New,York,,NY,,USA},, ,,,publisher,=,{ACM},, ,,,year,=,{2012},, ,,,isbn,=,{97841445034294349}, }, © 2012 David Schumm, Johanna Barzen, Frank Leymann, and Lutz Ellrich. A Pattern Language for Costumes in Films David Schumm1, Johanna Barzen2, Frank Leymann1, and Lutz Ellrich2 1 Institute of Architecture of Application Systems, University of Stuttgart, Universitätsstr. 38, 70569 Stuttgart, Germany. {schumm, leymann}@iaas.uni-stuttgart.de 2 Institute of Media Culture and Theater, University of Cologne, Meister-Ekkehard-Str. 11, 50937 Köln, Germany. {jbarzen, lutz.ellrich}@uni-koeln.de Abstract. A closer look behind the scenes of film making and media science reveals that the costumes used in film productions are products of a complex construction process. The costume designer has to put a lot of creative and investigative effort into the creation of costumes to provide the right clothes for a particular role, which means the costume reflects the place and time of play as well as it shows understanding of the characteristics of the role, actor and screenplay overall. -

Dolls in Tunics & Teddies in Togas

AIA Education Department Dolls in Tunics: Procedures Lesson Plans Dolls in Tunics & Teddies in Togas: A Roman Costume Project Sirida Graham Terk The Archer School for Girls Los Angeles, California Acknowledgements: Silvana Horn and Sue Sullivan origi- pertinent dress and status information, rather than require nated this project with the seventh-grade students of The research. S/he can give older students increased respon- Archer School for Girls in Los Angeles, California. It has sibility for research and hold them to higher standards of been refined and expanded over many years with the help costume quality and authenticity. High-school students and feedback of Theatre Arts teacher Emily Colloff, Archer can clothe bears as awards for younger students or as chari- students, and participants in the 2007 AIA Teacher Work- table donations, or create life-size garments for wearing to shop in San Diego. We appreciate the efforts and useful a Roman Feast (see the AIA lesson plan entitled Reclining suggestions of both educators and pupils! and Dining: A Greco-Roman Feast) or to Junior Classical League conventions. Overview Students research Roman dress and create small-scale ver- Goals sions of clothing for cloth dolls or teddy bears in this two- While students should become comfortable identifying, phase project, especially suited to a Latin or History class. producing, and handling items of Roman costume (or those We provide explicit instructions about materials, patterns, of another chosen culture), the primary goal is to learn how and techniques to make the teacher’s effort less daunting. clothing and accoutrements communicate age, gender, job, Students first learn about Roman dress and collect informa- and status within a society. -

Business Professional Dress Code

Business Professional Dress Code The way you dress can play a big role in your professional career. Part of the culture of a company is the dress code of its employees. Some companies prefer a business casual approach, while other companies require a business professional dress code. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR MEN Men should wear business suits if possible; however, blazers can be worn with dress slacks or nice khaki pants. Wearing a tie is a requirement for men in a business professional dress code. Sweaters worn with a shirt and tie are an option as well. BUSINESS PROFESSIONAL ATTIRE FOR WOMEN Women should wear business suits or skirt-and-blouse combinations. Women adhering to the business professional dress code can wear slacks, shirts and other formal combinations. Women dressing for a business professional dress code should try to be conservative. Revealing clothing should be avoided, and body art should be covered. Jewelry should be conservative and tasteful. COLORS AND FOOTWEAR When choosing color schemes for your business professional wardrobe, it's advisable to stay conservative. Wear "power" colors such as black, navy, dark gray and earth tones. Avoid bright colors that attract attention. Men should wear dark‐colored dress shoes. Women can wear heels or flats. Women should avoid open‐toe shoes and strapless shoes that expose the heel of the foot. GOOD HYGIENE Always practice good hygiene. For men adhering to a business professional dress code, this means good grooming habits. Facial hair should be either shaved off or well groomed. Clothing should be neat and always pressed. -

Femininity and Dress in fic- Tion by German Women Writers, 1840-1910

ORBIT-OnlineRepository ofBirkbeckInstitutionalTheses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output Scripts, skirts, and stays: femininity and dress in fic- tion by German women writers, 1840-1910 https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40147/ Version: Full Version Citation: Nevin, Elodie (2015) Scripts, skirts, and stays: femininity and dress in fiction by German women writers, 1840-1910. [Thesis] (Unpub- lished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email Scripts, Skirts, and Stays: Femininity and Dress in Fiction by German Women Writers, 1840-1910 Elodie Nevin Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in German 2015 Department of European Cultures and Languages Birkbeck, University of London Declaration for PhD thesis I have read and understood the regulations for students of Birkbeck, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. Signed: Date: 12/08/2015 2 Abstract This thesis examines the importance of sartorial detail in fiction by German women writers of the nineteenth century. Using a methodology based on Judith Butler’s gender theory, it examines how femininity is perceived and presented and argues that clothes are essential to female characterisation and both the perpetuation and breakdown of gender stereotypes. -

Wind Dancer Retreat Wedding Planning Guide

Wind Dancer Retreat Wedding Planning Guide © 2016 Wind Dancer Retreat www.winddancerretreat.com This wedding planning guide was prepared for couples to give them a starting point in planning their wedding. We meet many couples who come out to tour our venue who may not have considered many of these aspects of their wedding. We hope this wedding planning guide helps them prepare for their special day. The links provided throughout our e-book are not an endorsement, but meant to be used as helpful options in planning the details of your wedding. Congratulations on your engagement! You have found the groom and the ring, but now what about everything else? These upcoming months will be filled with exciting moments, lots of memories, and plenty of major decisions. Whether you’ve dreamed about this day and have been planning your wedding your entire life, or this is the first time you’ve given it any thought, don’t panic! We’re here to help. Hopefully with these easy-to-use resources from our Wedding Planning Guide, planning your wedding will be stress-free and fun as possible. Our idea behind writing this e-book was to help our brides ensure that every aspect of their wedding is given careful consideration, from catering to rehearsals to the vendors they choose. Throughout our e-book, we have included several links that can help you with making your budget, creating your guest list, deciding on a venue and much more! By conveniently putting all of our links into this one e-book that you can come back to again and again, this will save you many hours of searching the web. -

Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018

The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Front Cover Image: Textile Detail of an Evening Dress, circa 1950s, Maker Unknown, Middlesex University Fashion Collection, London, England, F2021AB. The Middlesex University Fashion Collection comprises approximately 450 garments for women and men, textiles, accessories including hats, shoes, gloves, and more, plus hundreds of haberdashery items including buttons and trimmings, from the nineteenth century to the present day. Browse the Middlesex University Fashion Collection at https://tinyurl.com/middlesex-fashion. The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 Editor–in–Chief Jennifer Daley Editor Scott Hughes Myerly Proofreader Georgina Chappell Published by The Association of Dress Historians [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org The Journal of Dress History Volume 2, Issue 3, Autumn 2018 [email protected] www.dresshistorians.org Copyright © 2018 The Association of Dress Historians ISSN 2515–0995 Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC) accession #988749854 The Journal of Dress History is the academic publication of The Association of Dress Historians through which scholars can articulate original research in a constructive, interdisciplinary, and peer reviewed environment. The Association of Dress Historians supports and promotes the advancement of public knowledge and education in the history of dress and textiles. The Association of Dress Historians (ADH) is Registered Charity #1014876 of The Charity Commission for England and Wales. The Journal of Dress History is copyrighted by the publisher, The Association of Dress Historians, while each published author within the journal holds the copyright to their individual article. The Journal of Dress History is circulated solely for educational purposes, completely free of charge, and not for sale or profit. -

Washington, Wednesday, March 8, 1950 TITLE 5

VOLUME 15 NUMBER 45 Washington, Wednesday, March 8, 1950 TITLE 5— ADMINISTRATIVE (e) “Promotion” is a change from one CONTENTS position to another position of higher PERSONNEL grade, while continuously employed in Agriculture Department Page the same agency. • Chapter I— Civil Service Commiyion See Commodity Credit Corpora (f) “Repromotion” is a change in po tion; Production and Marketing P art 25— F ederal E m plo y e e s ’ P a y sition from a lower grade back to a Administration. higher grade formerly held by the em R eg u latio n s Air Force Department ployee; or to- a higher intermediate SUBPART B— GENERAL COMPENSATION RULES grade, while continuously employed in Rules and regulations: Joint procurement regulations; Subpart B is redesignated as Subpart the same agency. (gp) “Demotion” is a change from one miscellaneous amendments E and a new Subpart B is added as set ( see Army Department). position to another position in a lower out below. These amendments are ef Alien Property, Office of fective the first day of the first pay grade, while continuously employed in period after October 28, 1949, the date the same agency. Notices: of the enactment of the Classification t (h) “Higher grade” is any GS or CPC Vesting orders, etc.: Behrman, Meta----- -------------- 1259 Act of 1949. * grade, the maximum scheduled rate of which is higher than the maximum Coutinho, Caro & Co. et al____ 1259 Sec. scheduled rate of the last previous GS Eickhoff, Mia, et al___________ 1260 25.101 Scope. or CPC grade held by the employee. Erhart, Louis_____------------— 1260 25.102 Definitions. -

Garden Fresh Salads Appetizers

APPETIZERS Chips & Dips Our crispy tortilla chips with your choice of dip. Salsa - 4 Fresh Guacamole - 8 Creamy Queso - 7 (Add Taco Meat or Pico de Gallo for 1.50 each) Spinach & Artichoke 8 Crispy corn tortilla chips with creamy spinach artichoke dip. Triple Dipper 11 Corn chips with salsa, queso & guacamole. Triple Dipper (Add artichoke for 3.00) Onion Rings 6 Hand breaded made to order. Cheese Sticks 8 Made fresh served with marinara. Fried Mushrooms 8 Crispy battered with side of honey mustard. Macho Nachos Tortilla chips topped with cheddar jack cheese, pinto beans, Buffalo Wings 9 sour cream and black bean corn pico. Jumbo traditional wings seasoned in our house rub, tossed Taco Meat or Fajita Chicken - 9 Fajita Beef - 11 in your choice of Honey BBQ or Buffalo Sauce. Served with (Add jalapenos and guacamole for additional charge) Ranch or Bleu Cheese dressing. Stuffed Avocado 8 Fresh avocado, chicken and monterey jack cheese in crispy breading. Served on a bed of rice. Pulled Pork Quesadillas 10 Tortilla stuffed with our tender, Carolina Style pulled pork and cheddar jack cheese. Southwest Quesadillas - Chicken 9 Beef 11 Tortilla stuffed with cheddar jack cheese, fajita meat and black bean corn pico. Macho Nachos GARDEN FRESH SALADS Dressings: Ranch, Jalapeno Ranch, Roasted Garlic Balsamic Vinaigrette, Thousand Island, Honey Mustard, Vidalia Onion & Bacon, Bleu Cheese and Strawberry Vinaigrette. Soup & Salad 7 Your choice of a House or Caesar side salad and a cup of our potato or green chile soup. Avocado Cobb Salad 10 NO CROUTONS Candied Pecan Mixed greens, fresh avocado, cheddar jack cheese, eggs, Strawberry Salad tomatoes, bacon bits, croutons and charbroiled chicken breast. -

Centro Cultural De La Raza Archives CEMA 12

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Online items available Guide to the Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives CEMA 12 Finding aid prepared by Project director Sal Güereña, principle processor Michelle Wilder, assistant processors Susana Castillo and Alexander Hauschild June, 2006. Collection was processed with support from the University of California Institute for Mexico and the United States (UC MEXUS). Updated 2011 by Callie Bowdish and Clarence M. Chan University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 (805) 893-8563 [email protected] © 2006 Guide to the Centro Cultural de la CEMA 12 1 Raza Archives CEMA 12 Title: Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives Identifier/Call Number: CEMA 12 Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Barbara, Davidson Library, Department of Special Collections, California Ethnic and Multicultural Archives Language of Material: English Physical Description: 83.0 linear feet(153 document boxes, 5 oversize boxes, 13 slide albums, 229 posters, and 975 online items)Online items available Date (inclusive): 1970-1999 Abstract: Slides and other materials relating to the San Diego artists' collective, co-founded in 1970 by Chicano poet Alurista and artist Victor Ochoa. Known as a center of indigenismo (indigenism) during the Aztlán phase of Chicano art in the early 1970s. (CEMA 12). Physical location: All processed material is located in Del Norte and any uncataloged material (silk screens) is stored in map drawers in CEMA. General Physical Description note: (153 document boxes and 5 oversize boxes).Online items available creator: Centro Cultural de la Raza http://content.cdlib.org/search?style=oac-img&sort=title&relation=ark:/13030/kt3j49q99g Access Restrictions None. -

Approximate Weight of Goods PARCL

PARCL Education center Approximate weight of goods When you make your offer to a shopper, you need to specify the shipping cost. Usually carrier’s shipping pricing depends on the weight of the items being shipped. We designed this table with approximate weight of various items to help you specify the shipping costs. You can use these numbers at your carrier’s website to calculate the shipping price for the particular destinations. MEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 70 - 100 Jacket 1000 - 1200 Sports shirt, T-shirt 220 - 300 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 UnderpantsShirt 70120 - -100 180 JacketWind-breaker 1000800 - -1200 1200 SportsBusiness shirt, suit T-shirt 2201200 - -300 1800 Coat,Autumn duster jacket 9001200 - -1500 1400 Sports suit 1000 - 1300 Winter jacket 1400 - 1800 Pants 600 - 700 Fur coat 3000 - 8000 Jeans 650 - 800 Hat 60 - 150 Shorts 250 - 350 Scarf 90 - 250 UnderpantsJersey 70450 - -100 600 JacketGloves 100080 - 140 - 1200 SportsHoodie shirt, T-shirt 220270 - 300400 Coat, duster 900 - 1500 WOMEN’S CLOTHES Item Weight in grams Item Weight in grams Underpants 15 - 30 Shorts 150 - 250 Bra 40 - 70 Skirt 200 - 300 Swimming suit 90 - 120 Sweater 300 - 400 Tube top 70 - 85 Hoodie 400 - 500 T-shirt 100 - 140 Jacket 230 - 400 Shirt 100 - 250 Coat 600 - 900 Dress 120 - 350 Wind-breaker 400 - 600 Evening dress 120 - 500 Autumn jacket 600 - 800 Wedding dress 800 - 2000 Winter jacket 800 - 1000 Business suit 800 - 950 Fur coat 3000 - 4000 Sports suit 650 - 750 Hat 60 - 120 Pants 300 - 400 Scarf 90 - 150 Leggings -

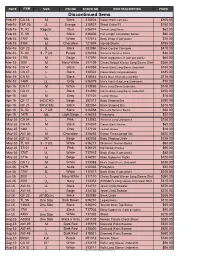

2017 Nefful Product Discontinued List

DATE ITEM SIZE COLOR STOCK NO. ITEM DESCRIPTION PRICE 2017 NeffulCO Product Discontinued List Discontinued Items Feb-16 CA 48 M Black 318026 Classic Black Camisole $105.00 Feb-16 DW 05 LL Orange 315937 Shawl Collar PJ $780.00 Feb-16 TL 52 Regular Blue 616074 Teviron Long Socks $62.00 Feb-16 TL 59 L Black 616406 Full Length Circulation Socks $90.00 Feb-16 1707 ML White 717014 Body Wrap (1 per pack) $70.00 Feb-16 3364 M Chocolate 121834 Hip-Up Shorts $155.00 Mar-16 QF 23 3L Black 382094 Black Control Camisole $410.00 Mar-16 TL 02 5 - 7 US Purple 616063 Women's Summer Socks $38.00 Mar-16 1705 M Beige 717091 Wrist supporters (1 pair per pack) $60.00 Mar-16 2001 M Navy-White 317109 Chess Striped Woven Long Sleeve Shirt $360.00 Mar-16 CA 41 M Black 314059 Classic Black Long-Sleeve Undershirt $150.00 Mar-16 CA 47 L Black 318024 Classic Black Long Underpants $185.00 Mar-16 CA 52 L Black 318044 Men's Black Short-Sleeved Shirt $178.00 Mar-16 1489 LL Gray 616079 Men's Tight-Fitting Long Underpants $70.00 Apr-16 CA 11 M White 313085 Men's Long-Sleeve Undershirt $148.00 Apr-16 CA 41 L Black 314060 Classic Black Long-Sleeve Undershirt $150.00 Apr-16 1461 M Gray 717101 Teviron Gloves $18.00 Apr-16 QF 11 36C(C80) Beige 382013 Body Shaping Bra $290.00 Apr-16 QF 21 38C(C85) Black 382064 Black Shaping Bra $315.00 Apr-16 TL 02 5 - 7 US Black 616058 Women's Summer Socks $38.00 Apr-16 1479 ML Light Beige 616033 Pantyhose $30.00 May-16 CA 04 L Pink 313082 Women's Long Underpants $150.00 May-16 CA 45 M Black 314067 Classic Black Panties $65.00 May-16 1461 L