Master-Finalv3.Odm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microsoft Word

UNION TERRITORY OF PONDICHERRY ELECTIONS DEPARTMENT REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 2006 TO THE PONDICHERRY LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY S. KUMARASWAMY, I.A.S., Chief Electoral Officer Pondicherry CONTENTS Page No. Foreword 1 PART-A : General Information 1. Schedule of Election Programme 5 2. General Note on Important Aspects 6 3. Important Election Officials a. Chief Electoral Officer & District Election Officers 9 b. Returning Officers & Assistant Returning Officers 10 c. Election Observers 12 4. List of participating Political Parties 14 5. Free Symbols 15 6. Highlights 16 7. Region and Assembly Constituency-wise Electorate details 18 8. Population and Electorate Comparison 19 9. Details of Polling Stations 20 10. Electorate Strength in Polling Stations 21 11. Details of Nominations 22 12. Details of Voter Turnout 23 13. Voter Turnout vis-à-vis the Electorate 24 14. Voter Identification - EPIC & other Documents 25 15. Details of Counting Centres 26 16. Winners and Runners-up at a Glance 27 17. Performance of Political Parties - Summary 29 18. Constituencies won by Political Parties 30 19. Poll Data at a Glance 31 PART B : Assembly Constituency-wise Information 33 PART C: Polling Station-wise votes polled 95 PART D: Assembly Elections over the years 165 Elections Department, No.31, Candappa Mudali Street S. KUMARASWAMY Pondicherry-605 001. Chief Electoral Officer Tel: 2334143, 2233307 Fax: 2337500 Email: [email protected] FOREWORD As the tenure of Legislative Assembly was due to expire on 08.06.2006, the notification calling upon the Electorate of the Union Territory of Pondicherry to elect the members of Pondicherry Legislative Assembly was issued by the Lt.Governor of Pondicherry on 5.04.2006 in respect of Mahe and Yanam regions and on 13.04.2006 in respect of Pondicherry and Karaikal regions and the Election Commission of India had also issued the notifications on the respective dates. -

18 March-2021.Qxd

C M C M Y B Y B RNI No: JKENG/2012/47637 Email: [email protected] POSTAL REGD NO- JK/485/2016-18 Internet Edition www.truthprevail.com Epaper: epaper.truthprevail.com Truth Prevail Morgan is a pioneer in white ball cricket: Buttler 3 5 12 Development of tourist destinations priority of Bhalla visited the actor Sanyam residence, Masoodi raises issues confronting UT Administration : Advisor Baseer Khan praised his acting talent in videos education sector in J&K in LS VOL: 10 Issue: 71 JAMMU AND KASHMIR, THURSDAy , MARCH 18 2021 DAILy PAGES 12 Rs. 2/- IInnssiiddee LG chairs review meeting of Smart City projects Ratle Hydroelectric Power Corporation Saurabh Bhagat JAMMU, MARCH 17 : Jammu and Srinagar into mod - directed for completing the sur - grounding of overhead utilities. to develop 850 MW Ratle HEP assumes charge Lieutenant Governor, Manoj ern and sustainable cities. vey at the earliest. He asked the For proper implementation Sinha today chaired a high- While reviewing the concerned officers to give due of Smart City Projects, the Lt Administrative Council approves Promoters’ Agreement of the JVC as DG J&K IMPARD level meeting to review the progress on installation of care and attention to reducing Governor directed for creating JAMMU, MARCH 17 : of India. for operationalization of the SRINAGAR, MARCH progress being made on the Advertisement Panels, the Lt inconvenience to the public in-house capacity for increas - The Administrative Council On the basis of the MoU Joint Venture Company. 17 : Saurabh Bhagat today prestigious Jammu and Governor observed that com - while executing the work. -

Microsoft Word

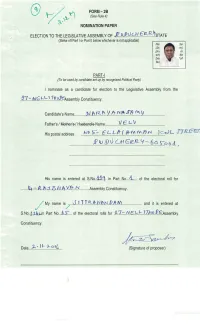

FORM-28 (See Rule 4) NOMINATION PAPER ELECTION TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF .J.?. VJ.?. ~ . ~U . f.~. ~~ STATE (Strike off Part I or Part II below whichever is not applicable) Re ize (2c m) phc in wh ite bac 'ull fac PART-I (To be used by candidate set up by recognised Political Party) I nominate as a candidate for election to the Legislative Assembly from the . 1. 7.~ . N.G..1:-:-:~ . ~..!..~ .~ft?Assembly Constituency. Candidate's Name........... .:>.J..A·g · ~ · .'/...It..~ . ~ . £fl . ~.9 .... ... .. ... ......... Father's I ~er's-1 Hlffibancfs Name..............V . ~ ..~ ..~............................. His postal address ...':-:1..~ ..?.."'::.... f.. ~ ..~. ft..f.. f!!:. ~.. '.!;, . !!. ~ ...... J.~ol L J'TfL<....'=EI ...... ... ........... .... g.Y. ..~..~.. ~~..l?~t3: . ~ . ~ .1?..9...SP o J . His name is entered at S.No ..~J~ . in Part No ...1-... of the electoral roll for ... ... .J4 .~ . P....Jt :J.. .13..l::f.I}..'I.ft..N. ........ ..Assembly Constituency. / My name is/ .. .J....1.. 1.'f. .~ . !r. N..hN..P../tM.................... and it is entered at S.No .J . i-~ . ~ n Part No...i£.. of the electoral! rolls for . i..7:-:-: . N . c. ~~.J71!P..RG. Assembly Constituency. Date...~..~ ..1.. 1. ~ .. ~ . ~ . ~ .t.. .. (S lgnature of proposer) 2 - , • P ,RT-Iii (To be used by candidate NOT et up by recognised Political Party) We hereby nominate- as candidat for election to the Legislative Assembly from the ....... ..t.'. ~ . f. ... l.Hl)lk .J..(f.f\\};e~y Constitue cy. Candidate's Name ... .. .......... ..rV.9.. C.b.J...f:..~. ) .. (ft.({. ~ . g_ .:...... .. Father's I Mother's I Husband's Narr e...... N. ~ . f.... ft..~!.. .~J.(; !?.. P..~ r.s:- His postal address .... -

Microsoft Word

FORM-28 r(iJ '\"'\ (See Rule 4) ~ ,'O'o NOMINATION PAPER ELECTION TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF J.Y.~..V..~ .~ . f. ~ . ~~.. STATE (Strike off Part I or Part II below whichever is not applicable) Re ize 1 (2c m) phi in wh 1ite bac full fa c PART-I (To be used by candidate set up by recognised Political Party) •.ri nominate as a candidate for election to the Legislative Assembly from the 17 .~ .. N . 9: . ~ . r .T~. ~f.!jssembly Constituency. Candidate's Name............N.A.r..: .A..'i. hr:!. ~S. 17..~..4..... .... ..... ............ Father's I ~s I Httsb~ Name .. .. ...... Y.. ~ .. ~ .. V. .... ............ ............... His postal address .... N.<?... ?.~ ... .f.i. b.!-::: . AJ/t.~ . M . fr . ~ ... ..~9..1 L- .J1}'12..e C:::-(T ........................... .. .....£ . ~~. ~ ..kl:r.£~4... : .fl...~ . r.~ "tJj_ . His name is entered at S.No.i11. in Part No .. ..i..... of the electoral rol'I for .....4.~I ..<.--:. .RA.X.Y.S.H. .fl Y.IJ .r.!. ... .... .. ......Assembly Constituency. ~ y name is ..... V..§ .. ~'l\. V./J . t-!.. ~....................... .. ...... and it is entered at S . No.~3 in Part No .. B.~ of the electoral rolls for .!1.:-:-.. t!.<?...~. ~ . 1.H.P.£. ~ ...Assembly ~ Constituency. Date ... ./..n .:. JJ..~...~ .? . ~ ~ (Signatu e of proposer) ' \ 2 , -;t;T-11 (To be used by candidate NOT ~et up by recognised Political Party) We hereby nominate as candida e for election to the Legislative Assembly from the ...... .. ........ ... ..IY. o. '1./}fJ{ ~Afsfrn~ 1 ~~ stitue ncy. Candidate's Name.. .. .. .. ........ .. ...... .. .. N..9..T.. .. .!J.t.f...~ J ..~ . /)..~ ..Y. ~ Father's I Mother's I Husband's Name ..........N.6.f .. l?..P.P. -

FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL PONDICHERRY STATE VETERINARY COUNCIL PUDUCHERRY-2021 Sl

PUBLICATION OF THE REVISED FINAL ELECTORAL ROLL PONDICHERRY STATE VETERINARY COUNCIL PUDUCHERRY-2021 Sl. Reg. Name and Date of Birth Residential Address Date of last Valid/ Remarks No. No. renewal Invalid Status 1. 1. Dr. K. Raghunathan SURABHI’ 21, 2nd Cross 02.01.2012 Valid Jan- Invalid S/o. C. Damodaran Sathya Nagar, Saram, 2017 11.06.1939 Puducherry-13. 2. 2. Dr. J. Muthuvaradan No.73, Thanthai Periyar 02.01.2012 Valid Jan- Deceased S/o. Janakiraman Nagar, Puducherry-5. 2017 22.06.1939 3. 3. Dr. L. Alfred Gnanou No.34, Needarajapaiyer 02.01.2012 Valid Jan- Invalid S/o. Louis Gnanou Street, Puducherry-1. 2017 15.07.1943 4. 4. Dr. R. Rajendiran No.38/A, 13.02.2017 Valid Mar- S/o. K. Radhakrishnan ‘Rasi Nivas’ 2022 05.04.1960 Plot No.5, Main Road, Anna Nagar Extn., Puducherry-5. 5. 5. Dr. J. Ernest Joseph No.102 (52), Saint 02.01.2012 Valid Jan- Deceased Raymond Therese Street, 2017 S/o. Jean Marie Puducherry-1. 01.05.1941 6. 6. Dr. K. Ganesan No.4, VII Cross, 18.01.2017 Valid Mar- S/o. Kathirvelu Bharathi Nagar, 2022 06.06.1954 Puducherry-8. 7. 7. Dr. T.P. Seetharaman B205, Manasarovar, 17.04.2017 Valid Mar- S/o. T. Padmanaban 19, 3rd Seaward Road, 2022 23.04.1942 Valmiki Nagar, Thiruvanmiyur, Chennai-600041. 8. 8. Dr. R. Rajmohan F Block, East Coast 31.03.2017 Valid Mar- S/o. N. Rajagopalan Apartments, 2022 26.12.1955 Mariamman Nagar, IIIrd Cross, Karamanikuppam, Puducherry-4. 9. 9. -

WHY Varun Gandhi? the Other Gandhi Who Has Carved a Niche for Himself Beyond His Haloed Family

Vol: 27 | No. 5 | May 2019| R20 www.opinionexpress.in A MONTHLY NEWS MAGAZINE Cover Story POLL POSITION Midway through India’s electoral Mahabharat, the battle is evenly poised Thank You BIPL %DODML,QIUD3URMHFWV/LPLWHG www.balaji.co.in www.dighiport.in editorial Modi factor holds the key for RNI UP–ENG 70032/92, Volume 27, No 5 EDITOR Prashant Tewari NDA II to make a comeback? ASSOCiate EDITOR ove him, hate him but people will keep his name on the board. Narendra Dr Rahul Misra Modi is the focal point of discussion either ways for the ongoing general elec- POLITICAL EDITOR tions in India. There is an extreme sharp division in the voters in favour or Prakhar Misra L against Narendra Modi in the entire country. News channels, news papers, social BUREAU CHIEF Anshuman Dogra (DELHI), Diwakar Shetty media reflects vertical division in the society. India was never more divided on (MUMBAI), Sidhartha Sharma (KOLKATA), ideological ground than it is today for the GE 2019. Rahul Gandhi led Congress is Lakshmi Devi (BANGALORE ) DIvyash Bajpai slightly better placed than in 2014, with state governments in (USA), KAPIL DUDAKIA (UNITED KINGDOM) Rajiv Agnihotri (MAURITIUS), Romil Raj M.P., Rajasthan and Chattisgarh under his belt – Congress Bhagat (DUBAI), Herman Silochan (CANADA), is poised for substantive gains. But with the reverses in the Dr Shiv Kumar (AUS/NZ), Nithya Ramesh recently concluded state elections, BJP has tighten its belt in (Fashion & Entertainment ) going ahead to the planning of the GE 2019. Narendra Modi CONTENT partner has rebranded himself round the garb of nationalism post The Pioneer Pratham Pravakta Pulwama attack and subsequent Balakot Air strike. -

Prelims Compass – Indian Polity and Governance

https://t.me/PDF4Exams << Download From >> https://t.me/IAS201819 Google it:- PDF4Exams https://t.me/PDF4Exams << Download From >> https://t.me/IAS201819 Google it:- PDF4Exams https://t.me/PDF4Exams << Download From >> https://t.me/IAS201819 CONTENTS Section-1 RESOLUTION 14 ►PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES 15 Basics of Constitution of India STANDING COMMITTEES 15 02 ►IMPORTANT COMMITTEES 16 ►FINANCIAL MATTERS 16 ►PREAMBLE 02 ►ANNUAL FINANCIAL STATEMENT - ARTICLE 112 16 ►INTERSTATE RIVER WATER DISPUTES ACT (IRWD ACT) 17 ►PART-III FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS (F.R.) 02 ►EMERGENCY PROVISIONS 17 ►STATE (ARTICLES 12) 03 ►ARTICLE-352 18 ►LAWS INCONSISTENT WITH FUNDAMENTAL RIGHTS & JUDICIAL REVIEW (ARTICLES 13) 03 ►ARTICLE 356 - FAILURE OF CONSTITUTIONAL MACHINERY IN STATE 18 ►RIGHT TO EQUALITY (ARTICLES 14-18) 03 ►FINANCIAL EMERGENCY – ARTICLE 360 18 ►RIGHT TO FREEDOM (ARTICLES 19-22) 04 ►RIGHT AGAINST EXPLOITATION (ARTICLES 23-24) 05 ►ROLE OF GOVERNOR 19 ►RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF RELIGION (ARTICLES 25-28) 05 ►DOES GOVERNOR PERFORM A DUAL FUNCTION? 19 ►CULTURAL AND EDUCATIONAL RIGHTS (ARTICLES 29-30) 06 ►CASE OF DELHI 19 ►RIGHT TO CONSTITUTIONAL REMEDIES (ARTICLE 32) 06 ►JAMMU & KASHMIR: GST AND ARTICLE 35A 21 ►DIRECTIVE PRINCIPLES OF STATE POLICY (DPSP) 06 ►NORTH EASTERN COUNCIL 21 ►DPSP CLASSIFICATION 07 ►PANCHAYATS 22 ►FUNDAMENTAL DUTIES (F.D.) 07 ►MUNICIPALITY 23 ►PARLIAMENT 08 ►97TH CONSTITUTIONAL AMENDMENT- ►PRESIDENT 08 COOPERATIVE 23 ►VICE-PRESIDENT 08 ►CONSTITUTIONAL BODIES 24 ►PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION 24 ►LOK SABHA 09 ►UNION PUBLIC SERVICE COMMISSION -

Decolonization, Migration, and Identity in France/India, 1910-1972

Transgressing the Boundaries of the Nation: Decolonization, Migration, and Identity in France/India, 1910-1972 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Jessica Louise Namakkal IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Patricia M.E. Lorcin, Adviser April 2013 ! Jessica Louise Namakkal 2013 ! "! Acknowledgements It is possible that I am not the first new Ph.D. to say this, but I really have had the best dissertation committee ever. I owe a huge debt of gratitude to my adviser, Patricia Lorcin, whose ‘Colonialism and Post-Colonialism’ course, offered during my first semester, built the foundation for my future work. She has provided years of feedback and support on different research topics, papers, and grant applications, and has taught me what it means to be a scholar engaged in the world outside the Academy. She has been a true mentor throughout this process, and I cannot thank her enough. Ajay Skaria has provided invaluable feedback and has opened many doors to my research and interests in South Asian studies; MJ Maynes, in addition to being my neighbor, has pushed me always to question categories, and to take every word I say and write seriously; Donna Gabbacia introduced me to the world of Migration Studies, and has been an inspiring figure of productivity and intellectual engagement; Jigna Desai has been an important source on issues of South Asian diaspora and has encouraged me to look critically at relations of sex and gender in the study of decolonization and diaspora.