Sample File This Page Intentionally Left Blank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Why So Serious?” Comics, Film and Politics, Or the Comic Book Film As the Answer to the Question of Identity and Narrative in a Post-9/11 World

ABSTRACT “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD by Kyle Andrew Moody This thesis analyzes a trend in a subgenre of motion pictures that are designed to not only entertain, but also provide a message for the modern world after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The analysis provides a critical look at three different films as artifacts of post-9/11 culture, showing how the integration of certain elements made them allegorical works regarding the status of the United States in the aftermath of the attacks. Jean Baudrillard‟s postmodern theory of simulation and simulacra was utilized to provide a context for the films that tap into themes reflecting post-9/11 reality. The results were analyzed by critically examining the source material, with a cultural criticism emerging regarding the progression of this subgenre of motion pictures as meaningful work. “WHY SO SERIOUS?” COMICS, FILM AND POLITICS, OR THE COMIC BOOK FILM AS THE ANSWER TO THE QUESTION OF IDENTITY AND NARRATIVE IN A POST-9/11 WORLD A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Communications Mass Communications Area by Kyle Andrew Moody Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2009 Advisor ___________________ Dr. Bruce Drushel Reader ___________________ Dr. Ronald Scott Reader ___________________ Dr. David Sholle TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................................... III CHAPTER ONE: COMIC BOOK MOVIES AND THE REAL WORLD ............................................. 1 PURPOSE OF STUDY ................................................................................................................................... -

Generic Transformation in the Superhero Film Genre by Noah Goodman

GENERIC TRANSFORMATION IN THE SUPERHERO FILM GENRE BY NOAH GOODMAN Reaffirmation of Myth: Humorous Burlesque: • Questions the • Pokes fun at the traditional heroic overused tropes of the values of the genre genre • Lighter, comedic tone • Reaffirms traditional • Graphic violence as heroic values as comedy being true • Non-heroic protagonist • Enforces the idea of • Satirizes interconnection (i.e. interconnected the MCU) superhero films INTRODUCTION: According to film genre theorist, John G. Cawelti, there are four modes at which a film genre can undergo generic transformation. Cawelti states these modes are “humorous burlesque, evocation of nostalgia, demythologization of generic myth, and the affirmation of myth as myth” (Cawelti 295). Despite it being a relatively new film genre, the superhero genre has already had a multitude of films to already fit these four modes declared by Cawelti. However, no other films express these four modes as greatly as Tim Miller’s Deadpool (2016), Patty Jenkin’s Wonder Woman (2017), James Mangold’s Logan (2017), and Joe and Anthony Russo’s Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014), respectively. DEFINITION OFTERMS: • Humorous Burlesque: tropes used in the genre are situated in a way to invoke laughter and are satirized • Evocation of Nostalgia: uses genre conventions to recreate aura of the past while establishing a relationship to the present • Demythologization: invokes the traditional genre conventions and demonstrates them as inadequate and destructive • Reaffirmation of Myth: questions genre conventions and ultimately reaffirmed at least partially Demythologization: Evocation of • More realistic tone Nostalgia: • Reference to myth as • Repisodic nostalgia being inadequate and based around pop false culture • Disillusioned • Traditional, heroic protagonist protagonist with • Shows the violence of unwavering beliefs super heroic actions • Thematic mending of • Darker promotional past and present material societal issues. -

Exhibit B: Business and Business Plan VIRAL FILMS MEDIA LLC

Exhibit B: Business and Business Plan VIRAL FILMS MEDIA LLC BUSINESS AND BUSINESS PLAN Viral Films Media LLC Producing an independent live-action superhero film: REBEL'S RUN Business Plan Summary Our recently formed company, Viral Films Media LLC, will produce, market and distribute an independently produced live-action superhero film, based on characters from the recently created Alt Hero comic book universe. The film will be titled Rebel’s Run, and will feature the character Shiloh Summers, or Rebel, from the Alt Hero comic book series. Viral Films has arranged to license a script and related IP from independent comic book publisher Arkhaven Comics, with comic book legend Chuck Dixon and epic fantasy author Vox Day co-writing the script. Viral Films Media is also partnering with Georgia and LA-based production company, Galatia Films, which has worked on hits including Goodbye, Christopher Robin and Reclaiming the Blade. The director of Rebel’s Run will be Scooter Downey, an up-and-coming director who recently co-produced Hoaxed, the explosive and acclaimed documentary on the fake news phenomenon. The filming of Rebel’s Run will take place in Georgia. We have formed a board of directors and management team including a range of professionals with experience in project management, law, film production and cyber-security. (image from Alt Hero, # 2, which introduced the character Shiloh Summers, or Rebel.) Film Company Overview Viral Films Media LLC (VFM) is a new film studio with the business purpose of creating a live-action superhero film – Rebel’s Run – based on characters from the ALT-HERO comic book universe created by Chuck Dixon, Vox Day and Arkhaven Comics. -

De Cómics, Narrativas Y Multiversos Transmediáticos: Re-Conceptualizando Al Hombre Araña En Spider-Man: Un Nuevo Universo

MHCJ Vol. 11 (2) | Año 2020 - Artículo nº10 (161) - Páginas 201 a 220 - mhjournal.org Fecha recepción: 30/03/2020 Fecha revisión: 21/05/2020 Fecha de publicación: 31/07/2020 De cómics, narrativas y multiversos transmediáticos: re-conceptualizando al hombre araña en Spider-Man: Un Nuevo Universo María Inmaculada Parra Martínez | [email protected] Universidad Católica San Antonio de Murcia, Murcia (España) Resumen Palabras clave “Animación”; “Cómic”; “Cultura-popular”; Este artículo examina la nueva versión animada de la franquicia “Narrativa”; “Spider-Man”; “Transmedia”. Spider-Man en términos de las elecciones narrativas y artísticas Sumario 1. Introducción. de sus creadores, para ofrecer una respuesta potencial acerca del 2. Contextualizando el Spider-Verso dentro de la franquicia de superhéroes. éxito de la película más aclamada por la crítica sobre el personaje 3. Vuelve la página: regreso al estilo cómic. arácnido. Teniendo en cuenta la complejidad que caracteriza a esta 3.1. Textura cómic. 3.2. Léxico de cómic. producción, especialmente con respecto a su historia, su densidad 4. Una red de múltiples dimensiones: el Spider-Verso como un universo Transmedia. técnica y su proyección transmedia, se emplea un enfoque 5. Conclusión. multidisciplinario para estudiar las múltiples dimensiones de esta 6. Bibliografía. película. Este artículo ofrece primero una contextualización del personaje del superhéroe y las diferentes historias que inspiraron la creación de esta, para luego presentar un análisis de su estilo artístico y la naturaleza transmedia de la misma. En particular, este artículo argumenta que la animación en formato cómic de esta película, combinada con la identidad transmedia de su narrativa, son las opciones más idóneas para la re-conceptualización de este personaje, ya que recuperan la esencia del género de superhéroes, a la vez que apelan a la dimensión social de su audiencia actual, de manera más efectiva que sus predecesores. -

October 2009 751 AERO MECHANIC Page

October 2009 751 AERO MECHANIC Page VOL. 64 NO. 9 OCTOBER 2009 Members ‘Coordinate’ New Process WTO Ruling Boeing Co. managers have turned to process, the Company is Could Give a team of experts to help develop a new utilizing the experience process for customer coordinators in and knowledge of Cus- Boeing Upper Everett, after initial process changes were tomer Coordinators . being reviewed by management for “We got off to a bad Hand for Tanker implementation. start,” Schuessler ac- Who are those experts? They are Dis- knowledged. “The team by Rosanne Tomyn trict 751 members who do the actual got it and didn’t like it.” On September 4 a controversial, work as liaisons between assembly work- “When it was first pro- yet expected, preliminary ruling was ers and airplane customers. moted to us, it had the made by the World Trade Organiza- By working with the Union and ask- feel that it was coming tion (WTO) that found European ing workers for their ideas, the Company whether we liked it or Union “launch aid” loans given to hopes to improve the Quality Assurance not,” said John Dyas, a Airbus were actually illegal subsi- process by identifying minor defects District 751 member and dies. After years of fighting to en- earlier in the process before the Cus- a team leader for the 777 sure that American tax dollars go to tomer inspections , said Susan Schuessler, customer coordinators in an American made Air Force Tanker, the Quality Director for 747, 767 and Everett. “We weren’t the ruling could prove positive for 777s in Everett. -

This Session Will Be Begin Closing at 6PM on 5/19/20, So Be Sure to Get Those Bids in Via Proxibid! Follow Us on Facebook & Twitter @Back2past for Updates

5/19 Bronze to Modern Comic Books, Board Games, & Toys 5/19/2021 This session will be begin closing at 6PM on 5/19/20, so be sure to get those bids in via Proxibid! Follow us on Facebook & Twitter @back2past for updates. Visit our store website at GOBACKTOTHEPAST.COM or call 313-533-3130 for more information! Get the full catalog with photos, prebid and join us live at www.proxibid.com/backtothepast! See site for full terms. LOT # QTY LOT # QTY 1 Auction Policies 1 13 Uncanny X-Men #350/Gambit Holofoil Cover 1 Holofoil cover art by Joe Madureira. NM condition. 2 Amazing Spider-Man #606/Black Cat Cover 1 Cover art by J. Scott Campbell featuring The Black Cat. NM 14 The Mighty Avengers Near Run of (34) Comics 1 condition. First Secret Warriors. Lot includes issues #1-23, 25-33, and 35-36. NM condition. 3 Daredevil/Black Widow Figure Lot 1 Marvel Select. New in packages. Package have minor to moderate 15 Comic Book Superhero Trading Cards 1 shelf wear. Various series. Singles, promos, and chase cards. You get all pictured. 4 X-Men Origins One-Shot Lot of (4) 1 Gambit, Colossus, Emma Frost, and Sabretooth. NM condition. 16 Uncanny X-Men #283/Key 1st Bishop 1 First full appearance of Bishop, a time-traveling mutant who can 5 Guardians of The Galaxy #1-2/Key 1 New roster and origin of the Guardians of the Galaxy: Star-Lord, absorb and redistribute energy. NM condition. Gamora, Drax, Rocket Raccoon, Adam Warlock, Quasar and 17 Crimson Dawn #1-4 (X-Men) 1 Groot. -

The Birth and Death of the Superhero Film

The Birth and Death of the Superhero Film RUNNING HEAD: The Superhero Film The Birth and Death of the Superhero Film Sander L. Koole Daniel Fockenberg Mattie Tops Iris K. Schneider VU University Amsterdam Draft: October 30, 2012 To appear in: Daniel Sullivan and Jeff Greenberg (Eds.) Fade to Black: Death in Classic and Contemporary Cinema KEYWORDS: Terror management, superhero, cinema Author Note Sander L. Koole, Department of Clinical Psychology, VU University Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Preparation of this chapter was facilitated by a Consolidator Grant from the European Research Council (ERC-2011-StG_20101124) awarded to Sander L. Koole. Address correspondence to Sander L. Koole, Department of Social Psychology, VU University Amsterdam, van der Boechorststraat 1, 1081 BT, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. Email: [email protected]. 1 The Birth and Death of the Superhero Film The Birth and Death of the Superhero Film In the late 1970s, when one of the authors of this chapter was at an impressionable age, his parents took him for the first time to a movie theatre. The experience was, in a single word, overwhelming. The epic music, accompanied by dazzling visuals and a delightful story, transported the young boy to a brand-new and brightly colored universe where just about anything seemed possible. When lights switched on and the credits appeared, our boy felt alive and bursting with energy. Indeed, as the movie ads had promised, he found himself believing that a man could fly. The movie, of course, was Richard Donner’s Superman (1978), the first superhero story to come out as a major feature film. -

1 Consider the Development of Imagery in the Superhero Film. Are

Consider the development of imagery in the superhero film. Are its expressive techniques more relevant to traditions of comics or cinema? Illustrate your answer with examples. From a level of camp that was attributed to early1 television and made-for-television film adaptations of superhero comics, to the realism and gritty German expressionist lens that coloured the likes of Superman (Richard Donner, 1978) and Batman (Tim Burton, 1989) respectively (Morton, 2016), the development of imagery in the superhero film has often teetered between the expressive techniques of cinema, and those of comics. According to Bukatman (2011: 118), today “the superhero film has displaced the superhero comic in the world of mass culture.” With this in mind, it is expedient to assess which medium’s expressive techniques the twenty-first century is more relevant to. Through the analysis of three films, this essay attempts to do exactly that. Before taking on this endeavour, however, it is important to establish what the yardstick of each medium’s expressive techniques is for this essay. Cinematic expressive techniques will be taken as the mise-en-scène2, soundtrack/score, the use of the star/celebrity, and visual effects. While the expressive techniques of comics will be taken as the use of panels, the elements within panels3, gutters, page-turns, and colour. The following three films will be analysed: Watchmen (Zack Snyder, 2009), a film that is said to be “very faithful” (Crocker, 2009) to the original comic book, but still appears “something less than the sum of its parts” (Bukatman, 2011:118); Thor: Ragnarok (Taika Waititi, 2017), the third instalment of the ‘Thor’ series which is most lauded for its evident “Jack Kirby influence” (Waititi, quoted in Blair, 2017); and Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (Ramsey, Rothman & Persichetti, 2018), which of the three chosen films is arguably the most relevant to the expressive techniques of comics, given its closeness to the medium as an animated film. -

Working Paper Series

Working Paper Series SPECIAL ISSUE: REVISITING AUDIENCES: RECEPTION, IDENTITY, TECHNOLOGY Superheroes and Shared Universes: How Fans and Auteurs Are Transforming the Hollywood Blockbuster Edmund Smith University of Otago Abstract: Over the course of the 2000s, the Hollywood blockbuster welcomed the superhero genre into its ranks after these films saw an explosion in popularity. Now, the ability to produce superhero films through an extended transmedia franchise is a coveted prize for major studios. The likes of Sony, 20th Century Fox, and Warner Bros. are locked in competition with the new kid on the block, Marvel, who changed the way Hollywood produces the blockbuster franchise. Drawing upon my previous and current postgraduate work, this essay will discuss fans and authorship in relation to the superhero genre which, I posit, exemplifies the industrial model of the Hollywood blockbuster and the cycle of appropriation and revitalisation that defines it. I will explain how studios like Marvel call upon up-and-coming directorial talent to further legitimise their films in order to appeal to middlebrow expectations through auteur credibility. Such director selection demonstrates: 1) how the contemporary auteur has become commodified within transmedia franchise blockbusters and, 2) how, due to the conflicting creative and commercial interests inherent to the blockbuster, these films are now supported by a form of co-dependent authorship. Related to this, I will also explore how fans function within this industrial context and the effect that their fannish support and promotion of superhero films has had on the latter’s viability as a staple of studio production. ISSN2253-4423 © MFCO Working Paper Series 3 MFCO Working Paper Series 2017 Introduction From the 2000s, through to the present day, the superhero film has seen a titanic increase in popularity, becoming a staple of the mainstream film industry. -

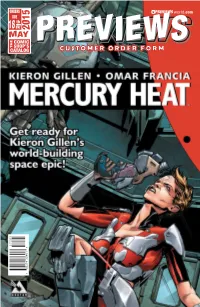

Customer Order Form

ORDERS PREVIEWS world.com DUE th 18 MAY 2015 MAY COMIC THE SHOP’S PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CATALOG CUSTOMER ORDER FORM CUSTOMER 601 7 May15 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 4/9/2015 2:47:37 PM May15 Dark Horse Ad.indd 1 4/9/2015 2:52:02 PM BARB WIRE #1 WE STAND ON DARK HORSE COMICS GUARD #1 IMAGE COMICS FREE COUNTRY: A TALE OF THE CHILDREN’S CRUSADE HC DC COMICS THE TOMORROWS #1 ISLAND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS IMAGE COMICS STAR TREK/ GREEN LANTERN #1 IDW PUBLISHING CYBORG #1 STAR WARS: DC COMICS LANDO #1 MARVEL COMICS May15 Gem Page ROF COF.indd 1 4/9/2015 2:55:25 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS 1 Archie Vs. Sharknado One-Shot l ARCHIE COMIC PUBLICATIONS Mercury Heat #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC The Spire #1 l BOOM! STUDIOS The Art of Mouse Guard: 2005-2015 HC l BOOM! STUDIOS Will Eisner’s The Spirit #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Bob’s Burgers #1 l D. E./DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT Invader Zim #1 l ONI PRESS INC. Nickelodeon Magazine #1 l PAPERCUTZ 1 Nickelodeon Magazine #2 l PAPERCUTZ The Book of Death #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT LLC The Demon Prince of Momochi House Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA LLC Awkward SC/HC l YEN PRESS Final Fantasy Type-0 Side Story Volume 1: Reaper Icy Blade GN l YEN PRESS Grimm Fairy Tales: Robyn Hood Omnibus TP l ZENESCOPE ENTERTAINMENT INC BOOKS The Best of Mike S. Miller Art Book HC l ART BOOKS The Hirschfeld Century HC l ART BOOKS Malefic Time: Apocalypse Volume 1 HC l ART BOOKS The Black Bat Double Novel Volume 1 l PULP HEROES 2 Star Wars: Jedi Academy Volume 3: The Phantom Bully HC l STAR WARS YOUNG READERS MAGAZINES DC -

Azbill Sawmill Co. I-40 at Exit 101 Southside Cedar Grove, TN 731-968-7266 731-614-2518, Michael Azbill [email protected] $6,0

Azbill Sawmill Co. I-40 at Exit 101 Southside Cedar Grove, TN 731-968-7266 731-614-2518, Michael Azbill [email protected] $6,000 for 17,000 comics with complete list below in about 45 long comic boxes. If only specific issue wanted email me your inquiry at [email protected] . Comics are bagged only with no boards. Have packed each box to protect the comics standing in an upright position I've done ABSOLUTELY all the work for you. Not only are they alphabetzied from A to Z start to finish, but have a COMPLETE accurate electric list. Dates range from 1980's thur 2005. Cover price up to $7.95 on front of comic. Dates range from mid to late 80's thru 2005 with small percentage before 1990. Marvel, DC, Image, Cross Gen, Dark Horse, etc. Box AB Image-Aaron Strain#2(2) DC-A. Bizarro 1,3,4(of 4) Marvel-Abominations 2(2) Antartic Press-Absolute Zero 1,3,5 Dark Horse-Abyss 2(of2) Innovation- Ack the Barbarion 1(3) DC-Action Comis 0(2),599(2),601(2),618,620,629,631,632,639,640,654(2),658,668,669,671,672,673(2),681,684,683,686,687(2/3/1 )688(2),689(4),690(2),691,692,693,695,696(5),697(6),701(3),702,703(3),706,707,708(2),709(2),712,713,715,716( 3),717(2),718(4),720,688,721(2),722(2),723(4),724(3),726,727,728(3),732,733,735,736,737(2),740,746,749,754, 758(2),814(6), Annual 3(4),4(1) Slave Labor-Action Girl Comics 3(2) DC-Advanced Dungeons & Dragons 32(2) Oni Press-Adventrues Barry Ween:Boy Genius 2,3(of6) DC-Adventrure Comics 247(3) DC-Adventrues in the Operation:Bollock Brigade Rifle 1,2(2),3(2) Marvel-Adventures of Cyclops & Phoenix 1(2),2 Marvel-Adventures -

1606 Industrial Hose Catalog 5-12-06.Indd

INDUSTRIAL HOSE Catalog 4800 ! WARNING FAILURE OR IMPROPER SELECTION OR IMPROPER USE OF THE PRODUCTS AND/OR SYSTEMS DESCRIBED HEREIN OR RELATED ITEMS CAN CAUSE DEATH, PERSONAL INJURY AND PROPERTY DAMAGE. This document and other information from Parker Hannifin Corporation, its subsidiaries and authorized distributors provide product and/or system options for further investigation by users having technical expertise. It is important that you analyze all aspects of your application, including conse- quences of any failure, and review the information concerning the product or system in the current product catalog. Due to the variety of operating conditions and applications for these products or systems, the user, through its own analysis and testing, is solely responsible for making the final selection of the products and systems and assuring that all performance, safety and warning requirements of the application are met. The products described herein, including without limitation, product features, specifications, designs, availability and pricing, are subject to change by Parker Hannifin Corporation and its subsidiaries at any time without notice. Offer of Sale The items described in this document are hereby offered for sale by Parker Hannifin Corporation, its subsidiaries or its authorized distributors. This offer and its acceptance are governed by the provisions stated in the full “Offer of Sale”. © Copyright 2006, Parker Hannifin Corporation. All Rights Reserved. MAPP® REGISTERED TRADEMARK AIRCO/BOC CORPORATION (USA) and CANADIAN LIQUID AIR