The Promise of Senior Judges

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remarks on Henry Friendly

REMARKS ON HENRY FRIENDLY ON THE AWARD OF THE HENRY FRIENDLY MEDAL TO JUSTICE SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR Pierre N. Leval † RESIDENT RAMO CALLED ME a couple of days ago with a problem. Young people today (and this includes young- sters up to the age of 50) apparently do not know who Henry Friendly was or why the American Law Institute Pawards a medal in his name. Would I address those questions to- night? At first I was astonished by Roberta’s proposition. Friendly was revered as a god in the federal courts from 1958 to his death in 1986. In every area of the law on which he wrote, during a quarter century on the Second Circuit, his were the seminal and clarifying opinions to which everyone looked as providing and explaining the standards. Most of us who earn our keep by judging can expect to be de- servedly forgotten within weeks after we kick the bucket or hang up the robe and move to Florida. But for one whose judgments played † Pierre Leval is a Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. He delivered these remarks on October 20, 2011, at a dinner of the Council of the American Law Insti- tute. Copyright © 2012 Pierre N. Leval. 15 GREEN BAG 2D 257 Pierre N. Leval such a huge role, it is quite surprising – and depressing – that the memory of him has so rapidly faded. Later, a brief exploration why this might be so. I begin by recounting, for any who don’t know, what some pur- ple-robed eminences of the law have said about Friendly. -

Annual Report

COUNCIL ON FOREIGN RELATIONS ANNUAL REPORT July 1,1996-June 30,1997 Main Office Washington Office The Harold Pratt House 1779 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. 58 East 68th Street, New York, NY 10021 Washington, DC 20036 Tel. (212) 434-9400; Fax (212) 861-1789 Tel. (202) 518-3400; Fax (202) 986-2984 Website www. foreignrela tions. org e-mail publicaffairs@email. cfr. org OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS, 1997-98 Officers Directors Charlayne Hunter-Gault Peter G. Peterson Term Expiring 1998 Frank Savage* Chairman of the Board Peggy Dulany Laura D'Andrea Tyson Maurice R. Greenberg Robert F Erburu Leslie H. Gelb Vice Chairman Karen Elliott House ex officio Leslie H. Gelb Joshua Lederberg President Vincent A. Mai Honorary Officers Michael P Peters Garrick Utley and Directors Emeriti Senior Vice President Term Expiring 1999 Douglas Dillon and Chief Operating Officer Carla A. Hills Caryl R Haskins Alton Frye Robert D. Hormats Grayson Kirk Senior Vice President William J. McDonough Charles McC. Mathias, Jr. Paula J. Dobriansky Theodore C. Sorensen James A. Perkins Vice President, Washington Program George Soros David Rockefeller Gary C. Hufbauer Paul A. Volcker Honorary Chairman Vice President, Director of Studies Robert A. Scalapino Term Expiring 2000 David Kellogg Cyrus R. Vance Jessica R Einhorn Vice President, Communications Glenn E. Watts and Corporate Affairs Louis V Gerstner, Jr. Abraham F. Lowenthal Hanna Holborn Gray Vice President and Maurice R. Greenberg Deputy National Director George J. Mitchell Janice L. Murray Warren B. Rudman Vice President and Treasurer Term Expiring 2001 Karen M. Sughrue Lee Cullum Vice President, Programs Mario L. Baeza and Media Projects Thomas R. -

Aviation Law Mark A

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 48 | Issue 2 Article 13 1983 Aviation Law Mark A. Dombroff Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Mark A. Dombroff, Aviation Law, 48 J. Air L. & Com. 453 (1983) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol48/iss2/13 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. Book Reviews AVIATION LAW by Andreas F. Lowenfeld. New York: Matthew Bender & Co., 1981 Edition. pp. 1411. In 1972, Andreas Lowenfeld published the first edition of AVIATION LAW.' In the introduction to that book, Professor Lowenfeld related the challenge presented by Judge Henry Friendly: Some years ago, Judge Henry Friendly, who made his career in large part as a brilliant and imaginative general counsel for Pan American World Airways, reviewed an earlier attempt to collect materials on aviation law by asking whether it made sense to treat this subject at all. "In order to make out a case for separate treatment," he wrote, "it must be shown that the heads of a given subject can be examined in a more illuminating fashion with reference to each other than with references to other branches of law." With respect to the book under review, Judge Friendly's answer was "a resounding no."' Professor Lowenfeld went on to accept the challenge and in the seven chapters of the first edition of AVIATION LAW presented the reader with an overview of the economic, regulatory, tort, and social considerations that have grown up in the law relating to the aviation industry. -

James Buchanan As Savior? Judicial Power, Political Fragmentation, and the Failed 1831 Repeal of Section 25

MARK A. GRABER* James Buchanan as Savior? Judicial Power, Political Fragmentation, and the Failed 1831 Repeal of Section 25 A ntebellum Americans anticipated contemporary political science when they complained about the tendency of embattled political elites to take refuge in the judiciary. Recent scholarship on comparative judicial politics suggests that judicial review is a means by which constitutional framers provided protection for certain class interests that may no longer be fully protected in legislative settings. Tom Ginsburg claims, "[I]f they foresee themselves losing in postconstitutional elections," the politicians responsible for the constitution "may seek to entrench judicial review as a form of political insurance." 1 Such a constitutional design ensures "[e]ven if they lose the election, they will be able to have some access to a forum in which to challenge the legislature."2 In 1801, Thomas Jefferson foreshadowed this strategy. He asserted that the defeated Federalist Party had "retired into the judiciary as a stronghold ...and from that battery all the works of republicanism are to be beaten down and erased.",3 More than a half century later, Chief Justice David S. *Professor of Law and Government, University of Maryland School of Law. This Article was written while the author was the 2008-09 Wayne Morse Chair at the University of Oregon School of Law. I am grateful to the Morse Foundation, Margaret Hallock, and Elizabeth Weber for their remarkable support. I am also grateful to numerous colleagues at the University of Maryland School of Law and elsewhere who read and commented on what follows without giggling too much. -

Judical Stratification and the Reputations of the United States Courts of Appeals

Florida State University Law Review Volume 32 Issue 4 Article 14 2005 Judical Stratification and the Reputations of the United States Courts of Appeals Michael E. Solimine [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael E. Solimine, Judical Stratification and the Reputations of the United States Courts of Appeals, 32 Fla. St. U. L. Rev. (2006) . https://ir.law.fsu.edu/lr/vol32/iss4/14 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW JUDICAL STRATIFICATION AND THE REPUTATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS Michael E. Solimine VOLUME 32 SUMMER 2005 NUMBER 4 Recommended citation: Michael E. Solimine, Judical Stratification and the Reputations of the United States Courts of Appeals, 32 FLA. ST. U. L. REV. 1331 (2005). JUDICIAL STRATIFICATION AND THE REPUTATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS MICHAEL E. SOLIMINE* I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................. 1331 II. MEASURING JUDICIAL REPUTATION, PRESTIGE, AND INFLUENCE: INDIVIDUAL JUDGES AND MULTIMEMBER COURTS ............................................................... 1333 III. MEASURING THE REPUTATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES COURTS OF APPEALS . 1339 IV. THE RISE AND FALL OF -

“Crisis”: Charting a Path for Federal Judiciary Reform

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce Law Faculty Scholarship School of Law 7-1-2020 Revisiting and Confronting the Federal Judiciary Capacity “Crisis”: Charting a Path for Federal Judiciary Reform Ryan G. Vacca University of New Hampshire School of Law, [email protected] Peter S. Menell University of California, Berkeley, School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/law_facpub Part of the Courts Commons, and the Judges Commons Recommended Citation 108 Cal. L. Rev. 789 (2020) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of New Hampshire – Franklin Pierce School of Law at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Revisiting and Confronting the Federal Judiciary Capacity “Crisis”: Charting a Path for Federal Judiciary Reform Peter S. Menell* and Ryan Vacca** The modern federal judiciary was established well over a century ago by the Judiciary Act of 1891. Over the next seventy years, the structure and core functioning of the judiciary largely remained unchanged apart from gradual increases in judicial slots. By the mid- 1960s, jurists, scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers had voiced grave concerns about the capacity of the federal system to function effectively in the face of ever-increasing caseloads. Heeding calls for reform, in 1972 Congress charged a commission chaired by Senator Roman Hruska to study the functioning of the federal courts and recommend reforms. -

Judicial Genealogy (And Mythology) of John Roberts: Clerkships from Gray to Brandeis to Friendly to Roberts

The Judicial Genealogy (and Mythology) of John Roberts: Clerkships from Gray to Brandeis to Friendly to Roberts BRAD SNYDER* During his Supreme Court nomination hearings, John Roberts idealized and mythologized the first judge he clerkedfor, Second Circuit Judge Henry Friendly, as the sophisticated judge-as-umpire. Thus far on the Court, Roberts has found it difficult to live up to his Friendly ideal, particularlyin several high-profile cases. This Article addresses the influence of Friendly on Roberts and judges on law clerks by examining the roots of Roberts's distinguishedyet unrecognized lineage of former clerks: Louis Brandeis 's clerkship with Horace Gray, Friendly's clerkship with Brandeis, and Roberts's clerkships with Friendly and Rehnquist. Labeling this lineage a judicial genealogy, this Article reorients clerkship scholarship away from clerks' influences on judges to judges' influences on clerks. It also shows how Brandeis, Friendly, and Roberts were influenced by their clerkship experiences and how they idealized their judges. By laying the clerkship experiences and career paths of Brandeis, Friendly, and Roberts side-by- side in detailed primary source accounts, this Article argues that judicial influence on clerks is more professional than ideological and that the idealization ofjudges and emergence of clerks hips as must-have credentials contribute to a culture ofjudicial supremacy. * Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin Law School. Thanks to Eleanor Brown, Dan Ernst, David Fontana, Abbe Gluck, Dirk Hartog, Dan -

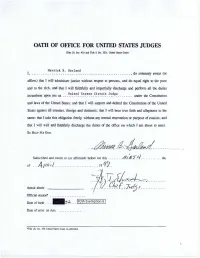

Previously Released Merrick Garland Docs

OATH OF OFFICE FOR UNITED STATES JUDGES (ritlc 28, Sec. 453 and Title 5. Sec. 3331. Unltr.d St.aleS Code) Merrick B. Garland I, ...... ............. .. .............. ....... .......... , do solemnly swear (or affinn) that I will administer justice without respect to persons, and do equal right to the poor and to the rich, and that I will faithfully and impartially discharge and perfonn all the duties . United States Circuit Judge . incumbent upon me as . under the Consucuuon and laws of the United States: and that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic: that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same: that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion: and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter. So HELP ME Goo. ... ..... u ~~- UL ... .·------_ Subscribed and swo ~ to (or affinned) before me this ....... Al.I. R '.T ~f.. ..... ... ... day of .. 4,pJ? .; ) .. ..................... 19 f.7 . -~ - ~~dL~-~~i ··· .. ..... Actual abode .... .. .< .~'- ~ { :- ~ 11J .~ ...... ..... ... Official station* ........... ...... Date of binh ... · · ·~?:- ... I~<?!~ Exemption 6 I Date of entry on duty .. ... ........ "'Titk lll S<?c. -1~6 u nited St.ate~ Code. as amended. v .o. \.JI·~ Of r"9'110tW'191 Menagemef'W FPM CMplllr IZle et-toe APPOINTMENT AFFIDAVITS United States Circuit Judge March 20, 1997 (POfition to wlticl appoif!Ud) (Dau o/ appoin~ U. S. Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit, Washington, DC (BuNau or Divilion) (Plau of tmp~t) Merrick B. Garland I, ----------------------• do solemnly swear (or affirm) that- A. -

Foreword BJI/CLR Symposium on Charting a Path for Federal Judiciary Reform

Foreword BJI/CLR Symposium on Charting a Path for Federal Judiciary Reform Jeremy Fogel* A principal mission of the Berkeley Judicial Institute (BJI), which I am privileged to serve as Executive Director, is to “fill a long-standing need to establish an effective bridge between the legal academy and the judiciary.” This mission statement reflects a common perception among both legal scholars and judges that the two institutions often talk past each other, such that the scholars’ analyses are insufficiently grounded in practical reality, while the judges’ perspectives are overly focused on granular detail. BJI’s existence reflects the hope that closer contact and collaboration between the two groups will lead to new and useful synergies. The Symposium on the structure and functioning of the federal appellate courts to which this issue of the California Law Review is dedicated was BJI’s first major public effort in pursuit of this goal. The Symposium brought together diverse thought leaders from academia, the bar, and the judiciary for two days of candid conversation and brainstorming. It expressly encouraged the participants to think big, to imagine how the federal courts might reframe their existing way of doing business to address functional deficiencies and serve their stakeholders more effectively. The results of the thought-provoking discussions are reflected in the seven pieces that CLR will publish: Professors Peter Menell and Ryan Vacca’s Revisiting and Confronting the Federal Judiciary Capacity “Crisis”: Charting a Path for Federal -

Project on Government Oversight to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States

July 9, 2021 Professor Bob Bauer and Professor Cristina Rodríguez, Co-Chairs Professor Kate Andrias, Rapporteur Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States Dear Professor Bauer, Professor Rodríguez, Professor Andrias, and Members of the Commission: Thank you for requesting written testimony from the Project On Government Oversight to the Presidential Commission on the Supreme Court of the United States. As a nonpartisan government watchdog, we believe strongly in the role of the federal judiciary and the Supreme Court in particular as a vital safeguard of individual rights and a critical check on abuse of power in our constitutional democracy. We are concerned, however, that the increased politicization of Supreme Court selection—coupled with the lack of proper accountability and transparency at the court—is damaging to checks and balances, as well as the legitimacy of this important institution. To address these concerns, last year we assembled the Task Force on Federal Judicial Selection to examine the causes of dysfunction in the selection of Supreme Court justices and to set out reforms. The timing of this invitation to provide testimony to the Presidential Commission is quite auspicious, as just yesterday we released the task force’s new report, Above the Fray: Changing the Stakes of Supreme Court Selection and Enhancing Legitimacy. Our task force includes two former chief justices of state supreme courts, Wallace Jefferson (Texas) and Ruth McGregor (Arizona); Timothy K. Lewis, a former judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit; and Judith Resnik, a legal scholar at Yale Law School. This group spent a year examining many of the same concerns that animate the Commission’s review, and we believe that the report could provide a useful blueprint for the work ahead of you. -

Tesi Enrico Andreoli VERS

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI VERONA DIPARTIMENTO DI SCIENZE GIURIDICHE SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO DI SCIENZE GIURIDICHE ED ECONOMICHE DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN SCIENZE GIURIDICHE EUROPEE ED INTERNAZIONALI CICLO / ANNO: XXXII / 2016 A CENTRALIZED ADJUDICATOR IN CONSTITUTIONAL ISSUES. UNA LETTURA CRITICA DEL MODELLO STATUNITENSE DI GIUSTIZIA COSTITUZIONALE S.S.D. IUS/21 Coordinatore: Prof.ssa Maria Caterina Baruffi __________________________ Tutor: Prof. Matteo Nicolini __________________________ Dottorando: Dott. Enrico Andreoli __________________________ Quest’opera è stata rilasciata con licenza Creative Commons Attribuzione – non commerciale Non opere derivate 3.0 Italia. Per leggere una copia della licenza visita il sito web: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/it/ Attribuzione. Devi riconoscere una menzione di paternità adeguata, fornire un link alla licenza e indicare se sono state effettuate delle modifiche. Puoi fare ciò in qualsiasi maniera ragionevole possibile, ma non con modalità tali da suggerire che il licenziante avalli te o il tuo utilizzo del materiale. Non Commerciale. Non puoi usare il materiale per scopi commerciali. Non opere derivate. Se remixi, trasformi il materiale o ti basi su di esso, non puoi distribuire il materiale così modificato. “A centralized adjudicator in constitutional issues. Una lettura critica del modello statunitense di giustizia costituzionale” Enrico Andreoli Tesi di Dottorato ISBN (da attribuire) INDICE INTRODUZIONE 4 CAPITOLO I LA GIUSTIZIA COSTITUZIONALE STATUNITENSE: UN MODELLO ESEMPLARE ALLA PROVA DELLA COMPARAZIONE Dal modello esemplare alla de-costruzione a fini classificatori. Proposte 1. 10 per un’indagine sulla giustizia costituzionale statunitense Oltre le costruzioni dell’idealtipo. Il versante interno della comparazione: 2. 19 genesi dell’ordinamento e consent al Judicial Review of Legislation (segue) Il balance di un Common Law ‘accentratore’: la Supreme Court 3. -

Charting a Path for Federal Judiciary Reform

Revisiting and Confronting the Federal Judiciary Capacity “Crisis”: Charting a Path for Federal Judiciary Reform Peter S. Menell* and Ryan Vacca** The modern federal judiciary was established well over a century ago by the Judiciary Act of 1891. Over the next seventy years, the structure and core functioning of the judiciary largely remained unchanged apart from gradual increases in judicial slots. By the mid- 1960s, jurists, scholars, practitioners, and policy-makers had voiced grave concerns about the capacity of the federal system to function effectively in the face of ever-increasing caseloads. Heeding calls for reform, in 1972 Congress charged a commission chaired by Senator Roman Hruska to study the functioning of the federal courts and recommend reforms. After extensive study, the Hruska Commission concluded that “[n]o part of the federal judicial system has borne the brunt of . increased demands [to protect individual rights and basic liberties and resolve difficult issues affecting the financial structure and commercial life of the nation] more than the courts of appeals.”1 The Commission called attention to the Supreme Court’s capacity constraints and the risks to the body of national law posed by the growing number of circuit conflicts. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38BK16Q3Q. Copyright © 2020 Peter S. Menell and Ryan Vacca. * Koret Professor of Law and Director, Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, University of California, Berkeley, School of Law. ** Professor of Law, University of New Hampshire School of Law. We thank the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts and the Federal Judicial Center for providing data on the federal judiciary and to Su Li for exceptional research assistance in formatting, synthesizing, and analyzing the data.