Mocking Terror After Thermidor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Practical Information

EN PRACTICAL INFORMATION The Memorial is a free public space open all year round, except during moments of flooding. VISITING ON YOUR OWN Open everyday. No reservation necessary. • from 9 am to 6 pm from 16 September to 14 May, • from 9 am to 8 pm from 15 May to 15 September. A MEMORIAL, Last access 30 minutes before closing time. Closed for maintenance in the last week of January. LEST WE GUIDED VISITS FORGET For groups, a tour “From history to memory” (museum + Memorial) is available. Reservation: • Tel.: +33 2 40 20 60 11 - Fax: +33 2 51 17 48 65 • [email protected] MEMORIAL TO THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY A STRUGGLE Quai de la Fosse TRAMWAY > line 1 FOR HUMAN (2017) STOP > Médiathèque or Chantiers Navals N VA www.memorial.nantes.fr L RIGHTS CHâTEAu dES duCS dE BretagNE MuSéE d’histoire dE NANTES 4, place Marc-Elder - From abroad : +33 2 51 17 49 48 TRAMWAY > line 1 omps – Jean-Dominique Billaud - T STOP > duchesse Anne - Château des ducs de Bretagne www.chateaunantes.fr The Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery is property of Nantes Métropole. Le Voyage à Nantes is responsible for its management as part of the public service delegation handling the Château des ducs de Bretagne and the Memorial to the Abolition of Slavery. : Franck credits hotographic P – ® L A MEMORIAL TO THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY ROSENTH A P www.memorial.nantes.fr A AP ON THE QUAY A COMMEMORATIVE ITINERARY Stretched out over 7000 m2 (75 000 sq. ft.) 2000 glass plaques can be This monument is one of the most found throughout the plant-covered important memorials in the world esplanade that runs alongside the devoted to the slave trade and its Loire River. -

The Price of Revolution Alison Patrick As Patrice Gueniffey Has Noted

The Price of Revolution 13 The Price of Revolution Alison Patrick As Patrice Gueniffey has noted, interest in the Terror as a French revolutionary phenomenon has waxed and waned, but has never disappeared, though focus and emphasis have changed from time to time. In preparation for the French 1789 bicentennial, Mitterand decided that France, unlike the United States, would not treat its revolutionary decade as a serial story, but would celebrate national liberation in a lump, with Chinese students wheeling empty bicycles at the head of the Bastille Day procession as a reminder that some countries had not yet caught up. This decision made it possible to avoid divisive areas, freeing the heirs of the Revolution to commemorate whatever they chose, but outside Paris, foreign visitors might find themselves puzzled by the range of local traditions which presumably shaped the festivities. (Exactly why did the Arles school children produce an exhibition of émigré biographies?) It would at least seem from the size and complexity of Gueniffey’s book that re-visits to the Terror are likely to continue.1 One realizes with surprise that one part of the story has still not had much attention. The normal focus has been on the development of Terror as an instrument of government policy, on the numbers and character of those affected by it, and on the crisis of Thermidor and its sequel. Gueniffey has a good deal about the political maneuvers that culminated in the events of Prairial, placing Robespierre in the centre of the stage, and the Thermidorians naturally get their share of notice. -

French Revolution Political Freedom!

French Revolution Part 2: Political Freedom! Part 2: Political Freedom! Objective: Understand what political freedom is. Determine what the right balance is between security and freedom. Assessment Goals: (Learning Target 1,2,3,6,7): Identify the changes in government and rights of people throughout the revolution. Determine when you believe people were the most free. Explain and defend using primary and secondary source evidence. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ A: Initial Revolutionary Movements _____________________________________________ Estates General Tennis Court Oath Storming of the Bastille http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/education/resources/french-revolution/source-2/ ‘The London Gazette’ – Saturday 18 July – Tuesday 21 July, 1789 (ZJ 1/85 Transcript In the Evening a Detachment with Two Pieces of Cannon went to the Bastile, to demand the Ammunition deposited there. A Flag of Truce had been sent before them, which was answered from within; But nevertheless, the Governor (the Marquis de Launay) ordered the Guard to fire, and several were killed. The Populace, enraged at this Proceeding, rushed forward to the Assault, when the Governor agreed to admit a certain Number, on Condition that they should not commit any Violence. A Detachment of about Forty accordingly passed the Drawbridge, which was instantly drawn up, and the whole Party massacred. This Breach of Faith, aggravated by so glaring an instance of Inhumanity, naturally excited a Spirit of revenge and Tumult not to be appeased. A Breach was soon made in the Gate, and the Fortress surrendered. The Governor, the principal Gunner, the Jailer, and Two old Invalids, who had been noticed as being more active than the Rest, were seized, and carried before the Council assembled at the Hotel de Ville, by whom the Marquis de Launay was sentenced to be beheaded, which was accordingly put in Execution at the Place de Grêve, and the other Prisoners were also put to Death. -

The French Revolution and Haiti, by Alex Fairfax-Cholmeley

52 III.2. The French Revolution and Haiti Alex Fairfax-Cholmeley Queen Mary, University of London Keywords: the Atlantic; Bourbon Restoration; National Convention; Paris Revolutionary Tribunal; Saint-Domingue; slavery; Thermidorian reaction I have become increasingly interested in the potential of using Saint- Domingue/Haiti as a prism through which to study French society during the Revolutionary era. Not only is the story of the revolution in Saint-Domingue important in its own right, but the complex and contradictory reactions it provoked back in the metropole offer an opportunity to put Revolutionary and counter-revolutionary principles under the microscope. The Haitian revolution was, after all, a test case for revolutionaries in France, who were debating the limits and potential of liberty and equality – as set against concerns over issues like the sanctity of private property, public order and geopolitical security. A Haitian prism on French politics has two further distinct advantages. First, it encourages, or perhaps even demands, a much broader timeframe than is usually employed in Revolutionary historiography, with French recognition of Haiti’s status as an independent nation in 1825 one obvious end point. Second, it leads naturally to engagement with the developing transnational e-France, volume 4, 2013, A. Fairfax-Cholmeley and C. Jones (eds.), New Perspectives on the French Revolution, pp.52-54. New Perspectives 53 historiography of the Atlantic world during this period – for example, work that looks at American condemnation and support for a successful slave rebellion in its vicinity. (Geggus and Friering, 2009; Sepinwall, 2012) This is therefore an opportunity to site French Revolutionary historiography in a truly international context. -

Researching Huguenot Settlers in Ireland

BYU Family Historian Volume 6 Article 9 9-1-2007 Researching Huguenot Settlers in Ireland Vivien Costello Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/byufamilyhistorian Recommended Citation The BYU Family Historian, Vol. 6 (Fall 2007) p. 83-163 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in BYU Family Historian by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. RESEARCHING HUGUENOT SETTLERS IN IRELAND1 VIVIEN COSTELLO PREAMBLE This study is a genealogical research guide to French Protestant refugee settlers in Ireland, c. 1660–1760. It reassesses Irish Huguenot settlements in the light of new findings and provides a background historical framework. A comprehensive select bibliography is included. While there is no formal listing of manuscript sources, many key documents are cited in the footnotes. This work covers only French Huguenots; other Protestant Stranger immigrant groups, such as German Palatines and the Swiss watchmakers of New Geneva, are not featured. INTRODUCTION Protestantism in France2 In mainland Europe during the early sixteenth century, theologians such as Martin Luther and John Calvin called for an end to the many forms of corruption that had developed within the Roman Catholic Church. When their demands were ignored, they and their followers ceased to accept the authority of the Pope and set up independent Protestant churches instead. Bitter religious strife throughout much of Europe ensued. In France, a Catholic-versus-Protestant civil war was waged intermittently throughout the second half of the sixteenth century, followed by ever-increasing curbs on Protestant civil and religious liberties.3 The majority of French Protestants, nicknamed Huguenots,4 were followers of Calvin. -

After Robespierre

J . After Robespierre THE THERMIDORIAN REACTION Mter Robespierre THE THERMIDORIAN REACTION By ALBERT MATHIEZ Translated from the French by Catherine Alison Phillips The Universal Library GROSSET & DUNLAP NEW YORK COPYRIGHT ©1931 BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC. ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED AS La Reaction Thermidorienne COPYRIGHT 1929 BY MAX LECLERC ET CIE UNIVERSAL LIBRARY EDITION, 1965 BY ARRANGEMENT WITH ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER: 65·14385 PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA PREFACE So far as order of time is concerned, M. M athie( s study of the Thermidorian Reaction, of which the present volume is a translation, is a continuation of his history of the French Revolution, of which the English version was published in 1928. In form and character, however, there is a notable difference. In the case of the earlier work the limitations imposed by the publishers excluded all references and foot-notes, and the author had to refer the reader to his other published works for the evidence on which his conclusions were based. In the case of the present book no such limitations have been set, and M. Mathiei: has thus been able not only to state his con clusions, but to give the chain of reasoning by which they have been reached. The Thermidorian Reaction is therefore something more than a sequel to The French Revolution, which M. Mathiei:, with perhaps undue modesty, has described as a precis having no independent authority; it is not only a work of art, but a weighty contribution to historical science. In the preface to his French Revolution M. -

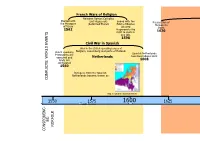

Refugee Timeline for Workshop

French Wars of Religion Between Roman Catholics Started with and Huguenots Ended with the the Massacre Persecution of (Reformed French Edict of Nantes Huguenots of Vassy Allowed starts 1562 Hugeneouts the 1620 right to work in any job. 1598 Civil War in Spanish War in the Dutch speaking areas of Belgium, Luxemburg and parts of Holland. Dutch speaking Spanish Netherlands Protestants are becomes independent executed and Netherlands lands are 1608 confiscated 1560 Refugees from the Spanish Netherlands became known as CONFLICTS: WORLD EVENTS Map showing the Spanish Nether- 1550 1575 1600 1625 Tudor Period ES: NORFOLK CONSEQUENC- French Persecution of Huguenots (Reformed French Protestants) The Dragonnades King Louis XIV of France encouraged soldiers to abuse French Protestants and destroy or steal their possessions. He wanted Huguenot families to leave France or convert to Catholicism. Edict of Fontainebleau Louis IX of France reversed the Edict of Nantes which stopped religious freedom for Protestants. 1685 King Louis XIV France French Flag before the French Revolution 1650 1675 170 1725 1750 1775 Stuart Period Russian persecution Ends with the Edict of of Jews Versailles which The Italian Wars of allowed non-Catholics to practice their Started with the May Laws. religion and marry Independence 1882 without becoming Jews forced to Catholic Individual states become live in certain 1787 independent from Austria and unite areas and not allowed in specific schools French Revolution or to do specific jobs. Public rebelled against the king and religious leaders. Resulted in getting rid of the King 1789-99 French Flag after the French Revolution Individual states which form 1775 1800 1825 1850 1875 1900 Georgian Period Victorian Period Russian persecution Second World War Congolese Wars Syrian Civil Global war involved the vast Repeal of the May Conflict involving nine African War majority of the world's nations. -

Bordeaux Et Nantes - Lyon Livret D’Information Salariés

FÉVRIER 2020 MISE EN CONCURRENCE DES LIGNES NANTES - BORDEAUX ET NANTES - LYON LIVRET D’INFORMATION SALARIÉS LE GOUVERNEMENT CONFIRME LA MISE EN CONCURRENCE DES LIGNES NANTES - BORDEAUX ET NANTES - LYON Les lignes de trains d’équilibre du territoire (TET) Nantes - Bordeaux et Nantes - Lyon sont actuellement exploitées par l’activité Intercités de SNCF Voyageurs, dans le cadre d’une convention avec l’État, autorité organisatrice (AO) des lignes TET. Cette convention, renouvelée en 2016, s’applique jusqu’à la fin de l’année 2020. Dans le cadre de l’ouverture à la concurrence des lignes ferroviaires françaises, prévue par la loi pour un nouveau pacte ferroviaire du 27 juin 2018, le gouvernement a publié le 27 janvier 2020 un avis de concession pour les lignes SNCF Nantes - Bordeaux et Nantes - Lyon. Cet avis de concession précise l’objet du futur contrat d’exploitation des lignes Nantes - Bordeaux et Nantes - Lyon, qui portera sur : - L’exploitation technique des deux liaisons ; - L’entretien courant et la maintenance des matériels roulants mis à disposition ; - La politique commerciale et tarifaire ; - La vente digitale et physique des titres de transport ; - La perception des recettes du service. Le futur exploitant pourra notamment recourir à des tiers pour la maintenance des matériels roulants et la distribution des titres de transport. La société SNCF Voyageurs, constituée le 1er janvier 2020, exploite les services de transport de voyageurs de longue distance (dont TGV INOUI, OUIGO et Intercités) et du quotidien (Transilien et TER). Elle est évidemment candidate à l’appel d’offres et répondra via une équipe dédiée au sein de l’activité Intercités. -

Fair Shares for All

FAIR SHARES FOR ALL JACOBIN EGALITARIANISM IN PRACT ICE JEAN-PIERRE GROSS This study explores the egalitarian policies pursued in the provinces during the radical phase of the French Revolution, but moves away from the habit of looking at such issues in terms of the Terror alone. It challenges revisionist readings of Jacobinism that dwell on its totalitarian potential or portray it as dangerously Utopian. The mainstream Jacobin agenda held out the promise of 'fair shares' and equal opportunities for all in a private-ownership market economy. It sought to achieve social justice without jeopardising human rights and tended thus to complement, rather than undermine, the liberal, individualist programme of the Revolution. The book stresses the relevance of the 'Enlightenment legacy', the close affinities between Girondins and Montagnards, the key role played by many lesser-known figures and the moral ascendancy of Robespierre. It reassesses the basic social and economic issues at stake in the Revolution, which cannot be adequately understood solely in terms of political discourse. Past and Present Publications Fair shares for all Past and Present Publications General Editor: JOANNA INNES, Somerville College, Oxford Past and Present Publications comprise books similar in character to the articles in the journal Past and Present. Whether the volumes in the series are collections of essays - some previously published, others new studies - or mono- graphs, they encompass a wide variety of scholarly and original works primarily concerned with social, economic and cultural changes, and their causes and consequences. They will appeal to both specialists and non-specialists and will endeavour to communicate the results of historical and allied research in readable and lively form. -

Reign of Terror Lesson Plan Central Historical Question

Reign of Terror Lesson Plan Central Historical Question: Was the main goal of the Committee of Public Safety to “protect the Revolution from its enemies”? Materials: • Copies of Timeline – Key Events of the French Revolution • Copies of Reign of Terror Textbook Excerpt • Copies of Documents A and B • Copies of Reign of Terror Guiding Questions Plan of Instruction: [NOTE: This lesson focuses on the Reign of Terror, the radical phase of the French Revolution that began in 1793. Students should be familiar with the general events of the French Revolution before participating in this lesson.] 1. Introduction: Hand out French Revolution Timeline. Read the paragraph on top together as a class. Use the timeline to review key events of the French Revolution leading up to the Reign of Terror. As you review these key events, you may want to emphasize the following: [Note: The timeline attempts to illustrate the increasing radicalization of the revolution between 1789 and 1792 by depicting the various governments that preceded the Committee of Public Safety. The main takeaway for students is that many people vied for power during the revolution; it was not a single, monolithic effort. The timeline does NOT attempt to tell the story of the Revolution, and in fact, does not include key events, such as the September Massacres, the king’s attempt to flee, etc.]. o The French Revolution began in 1789 (students should be familiar with the grievances of the Third Estate, storming of the Bastille, Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen). o Students should understand that the first phase of the French Revolution abolished the system of feudalism. -

73 Valence Tgv / Valence Ville Privas / Aubenas

VALENCE TGV / VALENCE VILLE PRIVAS / AUBENAS INFO TRAVAUX AUBENAS Travaux à partir de mars sur la ligne Lyon-Marseille. Impact probable sur les horaires de la ligne. Se renseigner auprès du transporteur ou sur cars.rhonealpes.fr 73 N’oubliez pas de vous reporter aux renvois ci-dessous PRIVAS CORRESPONDANCES - Arrivée des trains en gare de VALENCE VILLE (horaires donnés à titre indicatif, information auprès de la SNCF) TER En provenance de LYON 06.54 07.31 07.52 08.26 09.31 10.26 11.28 12.26 13.28 14.26 14.52 16.26 16.52 17.28 17.52 18.26 18.53 19.28 20.26 21.31 TER d’AVIGNON / MARSEILLE 05.58 07.05 07.31 07.58 08.28 09.31 11.31 13.31 14.28 17.31 17.56 18.28 18.58 19.31 20.25 21.26 21.45 VALENCE VILLE / TGV TGV de PARIS 10.14 14.11 20.17 22.11 73 Arrivée des trains en gare de VALENCE TGV HIVER HORAIRES DU 14 DÉCEMBRE 2014 AU 4 JUILLET 2015 TGV En provenance de PARIS 08.19 10.18 12.18 14.19 16.18 18.18 19.18 20.19 de RENNES 14.11 21.10 de NANTES 14.11 18.10 de BRUXELLES 11.10 14.39 20.44 de LILLE 09.45 11.10 14.39 19.44 20.44 de MONTPELLIER 08.15 10.12 11.46 15.41 16.13 17.13 17.44 18.41 19.13 21.15 de STRASBOURG 13.45 16.10 17.45 *sauf fêtes Lun Lun Lun Lun Sam, Dim Lun Lun Tous Lun Tous Lun Tous Tous Lun Tous Lun Lun Dim* Lun Lun Tous Lun Ven* Sauf Ven Lun Tous Lun Tous à Ven* à Ven* Sam* à Ven* Sam* à Ven* et Fêtes à Ven* à Ven* les jours à Sam* les jours à Sam* les jours les jours Sam* à Ven* les jours Sam* à Ven* à Sam* 1 à Ven* à Ven* les jours à Ven* 2 3 à Ven* les jours à Sam* les jours Sauf Sam VALENCE TGV RHÔNE-ALPES SUD 06.30 -

Dominique BERTRAND (Territoires Et Ville)

The French « modern streetcar Experience » Success stories Dominique BERTRAND (Territoires et ville) Date : 3 November 2016 Cerema (Centre for Studies and Expertise on Risks, Mobility, Land Planning and the Environment) • a State agency of scientific and technical expertise, in support of the definition, implementation and evaluation of public policies, on both national and local levels • placed under the supervision of the French Departments for sustainable development, town planning and transportation • 9 fields of operation 2 French tramways : the current situation 28 networks, 69 lines, near 500 miles Various size of town and networks, from 1 to 6 lines Rolling stock : 1350 cars from 22 to 44 meters long Basically, • Radial lines through city centres, based T4 Aulnay Bondy on traffic generation hotspots (universities, hospitals) et high density housing areas • Tram lines = base of re-structured PT T3 Lyon networks (2nd level when metro exists) * Till now, French LRT are mostly urban tramways TT Mulhouse Vallée de la Thur 3 The tram, a tool for High Level of Service Main indicators for H L S : • capacity, with a sufficient comfort • frequency (<10 mn) • commercial speed (>11 miles/h) + 2 fundamental indicators for quality: • regularity / ponctuality • reliability / availability infrastructure => a systemic approach : operation rolling stock 5 The French tramway revival a few historical networks • 2 surviving lines • a few renewal pioneers (Rouen, Nantes, Strasbourg, Grenoble, Paris) Then a great increase over last 20 years... Between 2000 & 2010 Networks with LRT X2 Number of Km X 3 LRT’s Ridership X 4 Still going on last years… Total length of streetcars lines from 1990 to 2010 to let streetcars run (back) in streets … we had to take the cars’ place ! Some favourable elements of context Accessibility rules (“handicap” law, Feb.